The Pareto Principle, commonly known as the 80/20 rule, has been a cornerstone of efficiency strategies for over a century. While its applications span industries—from business optimization to personal productivity—its limitations often go unaddressed. Below, we explore its historical roots, inherent flaws, and strategies to mitigate its pitfalls while identifying scenarios where alternative tools may yield better results.

From Wealth Distribution to Quality Control

Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist and sociologist (1848–1923), observed that 80% of Italy’s wealth was concentrated among 20% of its population. This “vital few vs. trivial many” concept later caught the attention of Joseph M. Juran, a pioneer in statistical quality control. Juran rebranded the principle as the Pareto Principle to describe how a minority of causes drive most effects in quality management, though he later acknowledged the misattribution to Pareto. Despite this, the 80/20 rule became synonymous with prioritization, emphasizing that focusing on the “vital few” could resolve the majority of problems.

Since then the 80/20 rule, or Pareto Principle, has become a dominant framework in business thinking due to its ability to streamline decision-making and resource allocation. It emphasizes that 80% of outcomes—such as revenue, profits, or productivity—are often driven by just 20% of inputs, whether customers, products, or processes. This principle encourages businesses to prioritize their “vital few” contributors, such as top-performing products or high-value clients, while minimizing attention on the “trivial many”. By focusing on high-impact areas, businesses can enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and achieve disproportionate results with limited effort. However, this approach also requires ongoing analysis to ensure priorities remain aligned with evolving market dynamics and organizational goals.

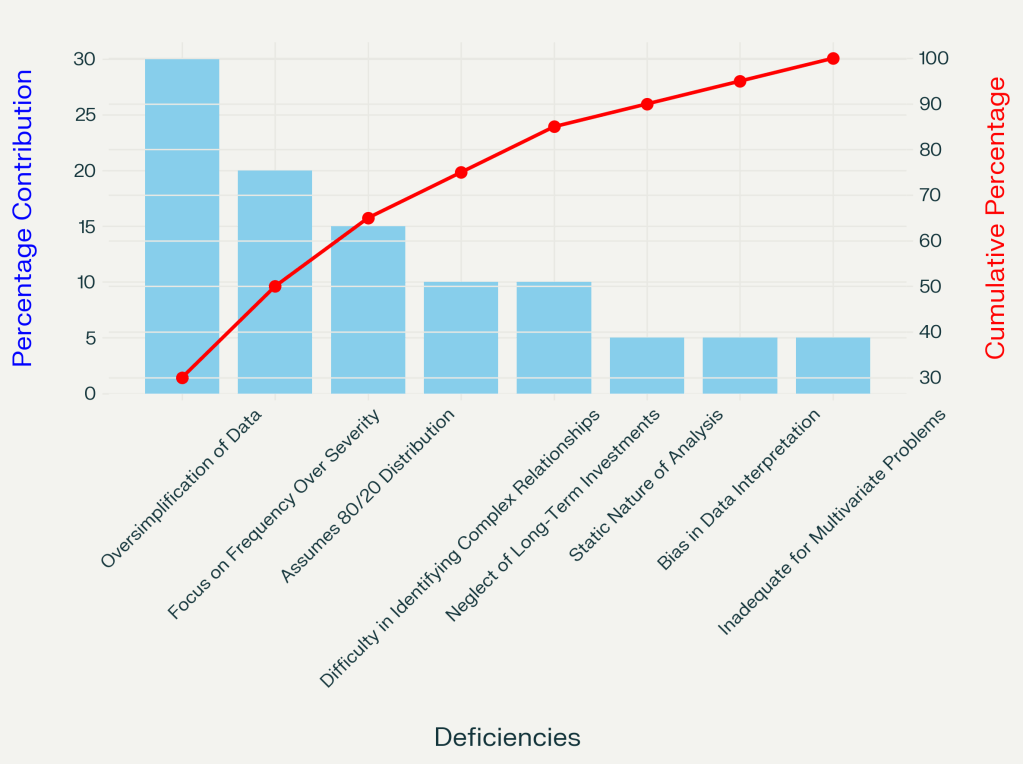

Key Deficiencies of the Pareto Principle

1. Oversimplification and Loss of Nuance

Pareto analysis condenses complex data into a ranked hierarchy, often stripping away critical context. For example:

- Frequency ≠ Severity: Prioritizing frequent but low-impact issues (e.g., minor customer complaints) over rare, catastrophic ones (e.g., supply chain breakdowns) can misdirect resources.

- Static and Historical Bias: Reliance on past data ignores evolving variables, such as supplier price spikes or regulatory changes, leading to outdated conclusions.

2. Misguided Assumption of 80/20 Universality

The 80/20 ratio is an approximation, not a law. In practice, distributions vary:

- A single raw material shortage might account for 90% of production delays in pharmaceutical manufacturing, rendering the 80/20 framework irrelevant.

- Complex systems with interdependent variables (e.g., manufacturing defects) often defy simple categorization.

3. Neglect of Qualitative and Long-Term Factors

Pareto’s quantitative focus overlooks:

- Relationship-building, innovation, or employee morale, which can be hard to quantify into immediate metrics but drive long-term success.

- Ethical equity: Pareto improvements (e.g., favoring one demographic without harming another) ignore fairness, risking inequitable outcomes.

4. Inability to Analyze Multivariate Problems

Pareto charts struggle with interconnected issues, such as:

- Cascade failures within a system, such as a bioreactor

- Cybersecurity threats requiring dynamic, layered solutions beyond frequency-based prioritization.

Mitigating Pareto’s Pitfalls

Combine with Complementary Tools

- Root Cause Analysis (RCA): Use the Why-Why to drill into Pareto-identified issues. For instance, if machine malfunctions dominate defect logs, ask: Why do seals wear out? → Lack of preventive maintenance.

- Fishbone Diagrams: Map multifaceted causes (e.g., “man,” “machine,” “methods”) to contextualize Pareto’s “vital few”.

- Scatter Plots: Test correlations between variables (e.g., material costs vs. production delays) to validate Pareto assumptions.

Validate Assumptions and Update Data

- Regularly reassess whether the 80/20 distribution holds.

- Integrate qualitative feedback (e.g., employee insights) to balance quantitative metrics.

Focus on Impact, Not Just Frequency

Weight issues by severity and strategic alignment. A rare but high-cost defect in manufacturing may warrant more attention than frequent, low-cost ones.

When to Redeem—or Replace—the Pareto Principle

Redeemable Scenarios

- Initial Prioritization: Identify high-impact tasks

- Resource Allocation: Streamline efforts in quality control or IT, provided distributions align with 80/20

When to Use Alternatives

| Scenario | Better Tools | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Complex interdependencies | FMEA | Diagnosing multifactorial supply chain failures |

| Dynamic environments | PDCA Cycles, Scenario Planning | Adapting to post-tariff supply chain world |

| Ethical/equity concerns | Cost-Benefit Analysis, Stakeholder Mapping | Culture of Quality Issues |

A Tool, Not a Framework

The Pareto Principle remains invaluable for prioritization but falters as a standalone solution. By pairing it with root cause analysis, ethical scrutiny, and adaptive frameworks, organizations can avoid its pitfalls. In complex, evolving, or equity-sensitive contexts, tools like Fishbone Diagrams or Scenario Planning offer deeper insights. As Juran himself implied, the “vital few” must be identified—and continually reassessed—through a lens of nuance and rigor.