On January 19, 2026, the EMA GMP/GDP Inspectors Working Group and PIC/S published a concept paper proposing a targeted revision of EU GMP Annex 15—Qualification and Validation. The public consultation opened on February 9 and runs through April 9, 2026. If you work in active substance manufacturing, or if your drug product quality depends on active substance quality—which is to say, if you work in this industry at all—this document deserves your attention.

The headline is straightforward: Annex 15 will become mandatory for active substance manufacturers. But what makes this revision significant isn’t just the shift from optional to mandatory. It’s what the shift reveals about where the regulatory landscape is heading, and how many of the themes I’ve been writing about on this blog—living risk management, control strategy as connective tissue, the validation lifecycle as a knowledge system—are now being codified into explicit regulatory expectations for a sector that has, frankly, lagged behind.

The Nitrosamine Wake-Up Call

The revision traces its origin directly to the N-nitrosamine crisis in sartan medicines. The EMA’s June 2020 lessons-learnt report was unsparing: one root cause of nitrosamine contamination was “the lack of sufficient process and product knowledge during the development stage and GMP deficiencies by active substance manufacturers, including inadequate investigation of quality issues and insufficient contamination control measures”. This wasn’t a novel finding at the time, but the sartans case gave regulators the political and scientific impetus to act.

Paragraph 4.2.2 of that lessons-learnt report specifically recommended making Annex 15 mandatory for active substance manufacturers to address the shortcomings identified during inspections. It took several years of deliberation—the GMP/GDP IWG formally agreed to proceed at its 115th meeting in September 2024—but the wheels are now turning.

The lesson here is one I’ve returned to repeatedly: knowledge gaps don’t stay dormant. They surface as deviations, contamination events, and regulatory actions. The sartans crisis was, at its core, a failure of process understanding and control strategy—areas where Annex 15 is now being strengthened precisely because too many active substance manufacturers treated validation as peripheral rather than foundational.

What the Concept Paper Actually Proposes

Let me walk through the key elements of the proposed revision, because the specifics matter more than the headline.

Scope Extension

The revised Annex 15 will apply to manufacturers of both chemical and biological active substances. EU and PIC/S inspectorates will enforce compliance during regulatory inspections. This is a paradigm shift for API manufacturers who have historically operated under Part II of the EU GMP Guide with Annex 15 as optional supplementary guidance. The concept paper is clear: “Although annex 15 is not currently mandatory for AS manufacturers, the applicability of its principles in this sector is generally recognised”. In other words, the expectation already existed—now it will have enforcement teeth.

Validation Master File, Policy, and Change Control

The concept paper proposes extending the Validation Master File, the Qualification and Validation Policy, and formal change control requirements to active substance manufacturers. These aren’t new concepts for drug product manufacturers, but their extension to AS manufacturers signals a regulatory expectation of structured, documented validation programs rather than ad hoc approaches.

Change control, in particular, is described as “an important part of knowledge management”. This language is deliberate and echoes what I’ve been writing about in the context of control strategies and the feedback-feedforward controls hub: change control isn’t bureaucratic overhead—it’s the mechanism through which accumulated process knowledge is preserved, evaluated, and applied.

Validation Discrepancies

The revision will extend the requirement to investigate results that fail to meet pre-defined acceptance criteria during validation activities. This extension, the concept paper notes, “will promote AS manufacturers to have a more in-depth knowledge of their processes.” This is one of the most quietly important provisions. In my experience, the gap between drug product and active substance manufacturers is often widest in investigation rigor. Robust investigation of validation failures isn’t just about compliance—it’s about generating the process knowledge that underpins meaningful control strategies.

Qualification Stages: URS, FAT/SAT, DQ/IQ/OQ/PQ

The concept paper extends the formal qualification lifecycle—User Requirements Specifications, Factory Acceptance Testing, Site Acceptance Testing, and the traditional DQ/IQ/OQ/PQ sequence—to active substance manufacturing. For those of us who have worked in the ASTM E2500 and ISPE commissioning and qualification frameworks, this is a natural evolution. As I discussed in my posts on CQV and engineering runs, these qualification stages aren’t separate activities—they form a continuum where each stage builds on the knowledge generated in the previous one. Extending this structured approach to API manufacturing strengthens the design-validation continuum that is essential for robust control strategies.

Process Validation: Development, Concurrent Validation, CPV, and Recovery

Several process validation enhancements are proposed:

- Emphasis on robust process development: Clarifying that validation begins with development, not with the first PPQ batch.

- Clarification of concurrent validation: Tightening expectations on when and how concurrent validation may be used.

- Continuous process verification and hybrid approaches: Extending Stage 3/CPV thinking to active substance manufacturing.

- Recovery of materials and solvents: Extending validation requirements to solvent and material recovery processes.

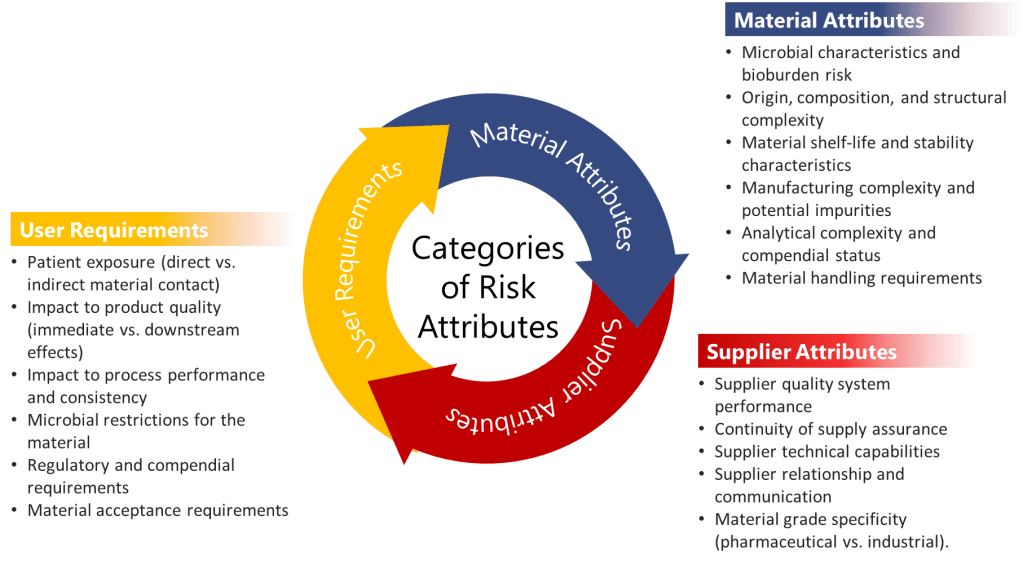

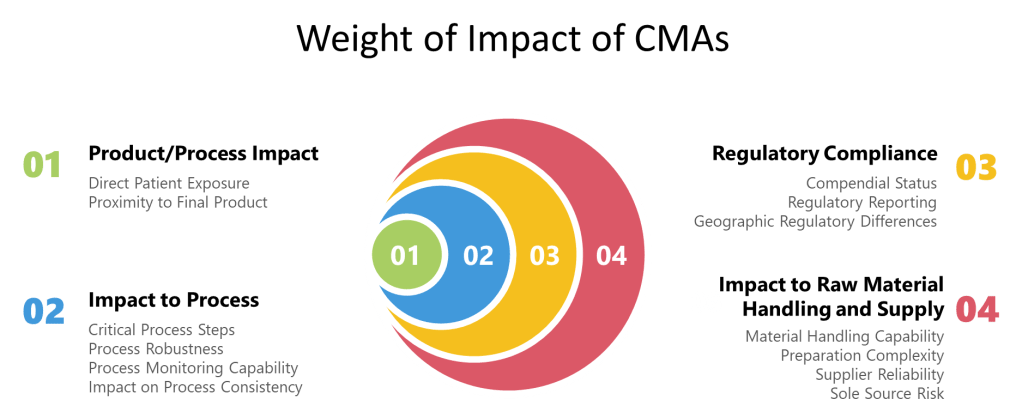

- Supplier qualification: Emphasizing the role of supplier qualification in the validation ecosystem.

- Periodic review: Reinforcing the expectation that validation is a lifecycle activity, not a one-time event.

This aligns directly with what I wrote about in Continuous Process Verification (CPV) Methodology and Tool Selection: CPV is “not an isolated activity but a continuation of the knowledge gained in earlier stages”. The lifecycle approach—Process Design (Stage 1), Process Qualification (Stage 2), Continued Process Verification (Stage 3)—is being explicitly extended to a sector that has too often treated validation as a discrete project rather than an ongoing program.

Transport Verification

The revision extends expectations for transport verification, linking GMP with Good Distribution Practices (GDP) for active substances. This addresses a gap that has been hiding in plain sight: product knowledge must include understanding of how transportation affects quality. For biologically-derived active substances in particular, this provision acknowledges that the supply chain is part of the process, not external to it.

ICH Q9 (R1) Integration

The concept paper mandates incorporation of ICH Q9 (R1) quality risk management principles throughout validation and qualification activities. Specifically:

- QRM in the design and validation/qualification of monitoring systems

- Risk review activities to support ongoing validation and qualification

- Emphasis on QRM in the context of traditional processes

This integration is overdue. As I discussed in Living Risk in the Validation Lifecycle and Risk Management is a Living Process, effective risk management isn’t a one-time exercise performed during design—it’s a living system that evolves throughout the product lifecycle. ICH Q9 (R1) itself emphasizes that “the level of effort, formality and documentation of the quality risk management process should be commensurate with the level of risk.” It introduces the importance-complexity-uncertainty framework for calibrating risk assessment rigor. The Annex 15 revision will make these principles explicitly applicable to qualification and validation decisions in active substance manufacturing.

Why This Matters: The Industry-Wide Implications

Closing the Knowledge Gap

The fundamental driver of this revision is a knowledge deficit. The nitrosamine crisis exposed what many of us already suspected: a significant number of active substance manufacturers lacked the process understanding necessary to predict, prevent, and detect quality problems. Making Annex 15 mandatory doesn’t automatically create knowledge, but it creates the structural requirements—validation master plans, formal qualification stages, investigation requirements, CPV programs—that force organizations to build and maintain it.

As I explored in Control Strategies, control strategies represent “the central mechanism through which pharmaceutical companies ensure quality, manage risk, and leverage knowledge”. Without the foundational process knowledge that structured validation generates, control strategies are hollow documents. The Annex 15 revision, by mandating the validation activities that generate this knowledge for active substance manufacturers, strengthens the entire control strategy ecosystem from the ground up.

From Compliance Burden to Audit Readiness

In my analysis of the 2025 State of Validation data, I noted a striking reversal: audit readiness has overtaken compliance burden as the industry’s primary validation challenge. This shift reflects a maturation of validation programs—organizations are moving from the scramble to implement validation to the discipline of sustaining it. The Annex 15 revision will push active substance manufacturers through a similar maturation arc. The initial impact will feel like compliance burden. But the long-term trajectory, if organizations approach it with the right mindset, is toward sustained audit readiness grounded in genuine process knowledge.

Risk Management as the Connective Thread

The integration of ICH Q9 (R1) throughout the revised Annex 15 reinforces a theme I’ve been tracking across multiple regulatory developments: risk management is no longer a supporting tool—it’s the connective thread that runs through every quality decision. The parallel revision of EudraLex Chapter 1, the new Annex 11 requirements for computerized systems, and the forthcoming Annex 22 for artificial intelligence all place quality risk management at their center. The Annex 15 revision ensures that qualification and validation are no exception.

This convergence means that organizations need integrated risk management capabilities—not siloed risk assessments performed by different teams for different purposes, but a coherent QRM framework that connects design risk, process risk, facility risk, and supply chain risk into a unified picture. As I wrote in my piece on risk management and change management: “Risk management leads to change management. Change management contains risk management”. The revised Annex 15 makes this cycle explicit for active substance manufacturers.

The Control Strategy Connection

Perhaps the most significant implication is how this revision strengthens the link between validation and control strategy. In Control Strategies, I described how control strategies occupy “that critical program-level space between overarching quality policies and detailed operational procedures” and serve as “the blueprint for how quality will be achieved, maintained, and improved throughout a product’s lifecycle”.

The Annex 15 revision reinforces every dimension of this blueprint for active substance manufacturing:

- Validation Master File → documents the overall validation approach and connects it to the control strategy

- Formal qualification stages → ensure that facility and equipment design supports the intended control strategy

- Process validation with CPV → generates the ongoing data that validates and refines the control strategy

- Investigation of failures → feeds new knowledge back into the control strategy through the feedback loop

- Change control as knowledge management → ensures that the control strategy evolves based on accumulated understanding

- Transport verification → extends the control strategy to encompass the supply chain

This is the feedback-feedforward controls hub in action. Each element of the revised Annex 15 either generates knowledge that feeds into the control strategy or applies knowledge from the control strategy to operational decisions.

The PLCM Document and Established Conditions

Looking forward, this revision also has implications for how active substance manufacturers engage with ICH Q12 concepts. As I discussed in my recent post on the Product Lifecycle Management (PLCM) document, the distinction between comprehensive control strategy elements and Established Conditions is critical for enabling continuous improvement. Active substance manufacturers who build robust validation and knowledge management programs now—in response to the Annex 15 revision—will be better positioned to participate in lifecycle management frameworks that reward process understanding with regulatory flexibility.

The concept paper’s emphasis on “change control as an important part of knowledge management” directly supports this trajectory. Organizations that treat change control as a bureaucratic hurdle will miss the point. Those that treat it as a knowledge capture mechanism will find themselves building the foundation for more sophisticated lifecycle management.

The Timeline and What to Do Now

The proposed timetable is aggressive:

| Milestone | Date |

| Concept paper public consultation | February – April 2026 |

| Draft guideline consultation | April – June 2026 |

| EMA GMP/GDP IWG endorsement | July 2026 |

| Publication by European Commission | December 2026 |

| PIC/S adoption | December 2026 |

The concept paper includes four stakeholder questions that are worth engaging with seriously:

- What is the current level of use of Annex 15 principles in active substance manufacturing?

- What would be the impact of making Annex 15 mandatory?

- What is the current understanding and use of ICH Q9 (R1) in active substance manufacturing?

- What would be the impact of incorporating Q9 (R1)?

If you manufacture active substances—or if you’re a drug product manufacturer who depends on active substance suppliers—now is the time to:

- Perform a gap assessment against the current Annex 15 requirements, assuming mandatory application

- Evaluate your Validation Master Plan or equivalent program documentation for active substance operations

- Review your qualification lifecycle to ensure URS, FAT/SAT, and formal qualification stages are documented and traceable

- Assess your CPV program for active substance processes—does it exist? Is it generating actionable knowledge?

- Examine your investigation process for validation failures against pre-defined acceptance criteria

- Review your QRM integration into qualification and validation activities against ICH Q9 (R1) expectations

- Engage with the public consultation by the April 9, 2026 deadline

The Bigger Picture

The concept paper notes that the GMP/GDP IWG also agreed that “a comprehensive review of Annex 15 should be initiated in the future, once the current targeted revision is finished”. This targeted revision is just the beginning. A full-scope revision will likely address the broader evolution of validation thinking—digital systems, advanced analytics, platform approaches—that I’ve been tracking in posts on the evolving validation landscape.

The world of validation is no longer controlled by periodic updates or leisurely transitions. Change is the new baseline. The Annex 15 revision is another data point in a pattern that includes the Annex 1 overhaul, the Annex 11 modernization, the introduction of Annex 22, the ICH Q9 (R1) revision, and the convergence of global regulators around lifecycle, risk-based, and knowledge-driven approaches to quality.

For active substance manufacturers, the message is clear: the era of treating validation as optional supplementary guidance is over. For the rest of us, the message is equally important: the quality of our medicines depends on the quality of knowledge throughout the supply chain, and regulators are now ensuring that the structural requirements to generate and maintain that knowledge extend to every link in the chain.