As quality professionals, we can often fall into the trap of believing that more analysis, more data, and more complex decision trees lead to better outcomes. But what if this fundamental assumption is not just wrong, but actively harmful to effective risk management? Gerd Gigerenzer‘s decades of research on bounded rationality and fast-and-frugal heuristics suggests exactly that—and the implications for how we approach quality risk management are profound.

The Myth of Optimization in Risk Management

Too much of our risk management practice assumes we operate like Laplacian demons—omniscient beings with unlimited computational power and perfect information. Gigerenzer calls this “unbounded rationality,” and it’s about as realistic as expecting your quality management system to implement itself.

In reality, experts operate under severe constraints: limited time, incomplete information, constantly changing regulations, and the perpetual pressure to balance risk mitigation with operational efficiency. How we move beyond thinking of these as bugs to be overcome, and build tools that address these concerns is critical to thinking of risk management as a science.

Enter the Adaptive Toolbox

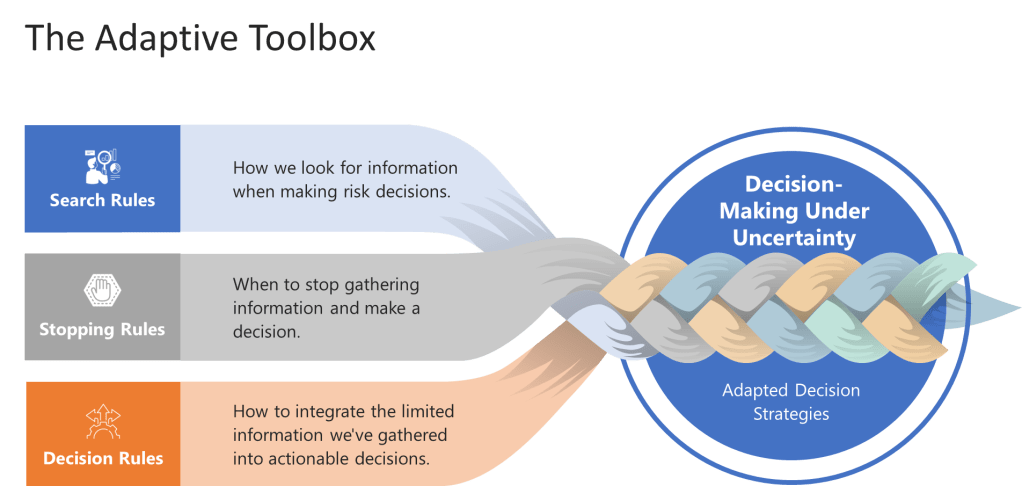

Gigerenzer’s adaptive toolbox concept revolutionizes how we think about decision-making under uncertainty. Rather than viewing our mental shortcuts (heuristics) as cognitive failures that need to be corrected, the adaptive toolbox framework recognizes them as evolved tools that can outperform complex analytical methods in real-world conditions.

The toolbox consists of three key components that every risk manager should understand:

Search Rules: How we look for information when making risk decisions. Instead of trying to gather all possible data (which is impossible anyway), effective heuristics use smart search strategies that focus on the most diagnostic information first.

Stopping Rules: When to stop gathering information and make a decision. This is crucial in quality management where analysis paralysis can be as dangerous as hasty decisions.

Decision Rules: How to integrate the limited information we’ve gathered into actionable decisions.

These components work together to create what Gigerenzer calls “ecological rationality”—decision strategies that are adapted to the specific environment in which they operate. For quality professionals, this means developing risk management approaches that fit the actual constraints and characteristics of pharmaceutical manufacturing, not the theoretical world of perfect information.

The Less-Is-More Revolution

One of Gigerenzer’s most counterintuitive findings is the “less-is-more effect”—situations where ignoring information actually leads to better decisions. This challenges everything we think we know about evidence-based decision making in quality.

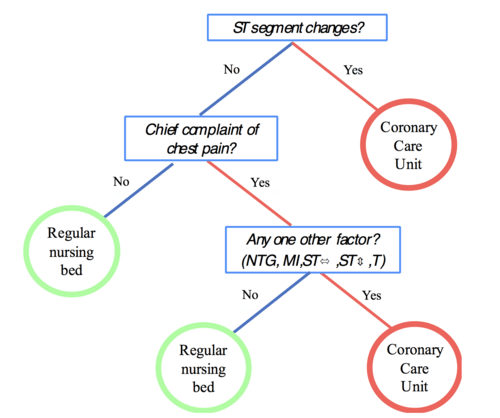

Consider an example from emergency medicine that directly parallels quality risk management challenges. When patients arrive with chest pain, doctors traditionally used complex diagnostic algorithms considering up to 19 different risk factors. But researchers found that a simple three-question decision tree outperformed the complex analysis in both speed and accuracy.

The fast-and-frugal tree asked only:

- Are there ST segment changes on the EKG?

- Is chest pain the chief complaint?

- Does the patient have any additional high-risk factors?

Based on these three questions, doctors could quickly and accurately classify patients as high-risk (requiring immediate intensive care) or low-risk (suitable for regular monitoring). The key insight: the simple approach was not just faster—it was more accurate than the complex alternative.

Applying Fast-and-Frugal Trees to Quality Risk Management

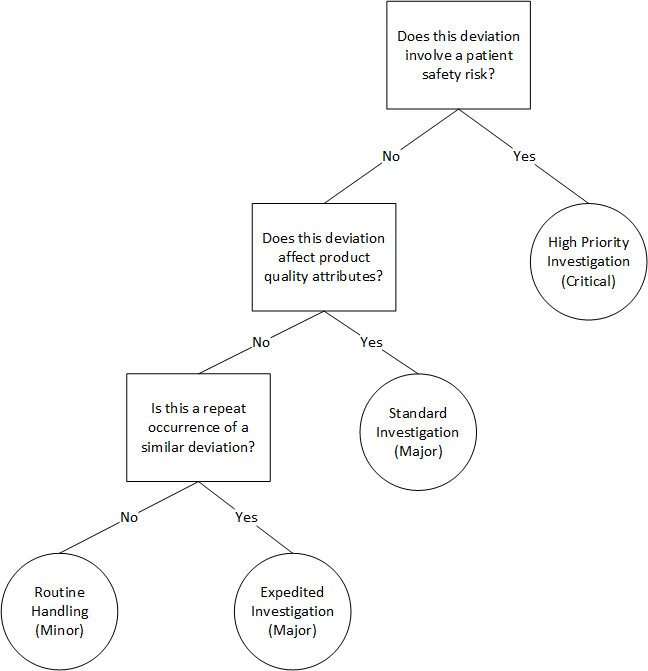

This same principle applies directly to quality risk management decisions. Too often, we create elaborate risk assessment matrices that obscure rather than illuminate the critical decision factors. Fast-and-frugal trees offer a more effective alternative.

Let’s consider deviation classification—a daily challenge for quality professionals. Instead of complex scoring systems that attempt to quantify every possible risk dimension, a fast-and-frugal tree might ask:

- Does this deviation involve a patient safety risk? If yes → High priority investigation (exit to immediate action)

- Does this deviation affect product quality attributes? If yes → Standard investigation timeline

- Is this a repeat occurrence of a similar deviation? If yes → Expedited investigation, if no → Routine handling

This simple decision tree accomplishes several things that complex matrices struggle with. First, it prioritizes patient safety above all other considerations—a value judgment that gets lost in numerical scoring systems. Second, it focuses investigative resources where they’re most needed. Third, it’s transparent and easy to train staff on, reducing variability in risk classification.

The beauty of fast-and-frugal trees isn’t just their simplicity. It is their robustness. Unlike complex models that break down when assumptions are violated, simple heuristics tend to perform consistently across different conditions.

The Recognition Heuristic in Supplier Quality

Another powerful tool from Gigerenzer’s adaptive toolbox is the recognition heuristic. This suggests that when choosing between two alternatives where one is recognized and the other isn’t, the recognized option is often the better choice.

In supplier qualification decisions, quality professionals often struggle with elaborate vendor assessment schemes that attempt to quantify every aspect of supplier capability. But experienced quality professionals know that supplier reputation—essentially a form of recognition—is often the best predictor of future performance.

The recognition heuristic doesn’t mean choosing suppliers solely on name recognition. Instead, it means understanding that recognition reflects accumulated positive experiences across the industry. When coupled with basic qualification criteria, recognition can be a powerful risk mitigation tool that’s more robust than complex scoring algorithms.

This principle extends to regulatory decision-making as well. Experienced quality professionals develop intuitive responses to regulatory trends and inspector concerns that often outperform elaborate compliance matrices. This isn’t unprofessional—it’s ecological rationality in action.

Take-the-Best Heuristic for Root Cause Analysis

The take-the-best heuristic offers an alternative approach to traditional root cause analysis. Instead of trying to weight and combine multiple potential root causes, this heuristic focuses on identifying the single most diagnostic factor and basing decisions primarily on that information.

In practice, this might mean:

- Identifying potential root causes in order of their diagnostic power

- Investigating the most powerful indicator first

- If that investigation provides a clear direction, implementing corrective action

- Only continuing to secondary factors if the primary investigation is inconclusive

This approach doesn’t mean ignoring secondary factors entirely, but it prevents the common problem of developing corrective action plans that try to address every conceivable contributing factor, often resulting in resource dilution and implementation challenges.

Managing Uncertainty in Validation Decisions

Validation represents one of the most uncertainty-rich areas of quality management. Traditional approaches attempt to reduce uncertainty through exhaustive testing, but Gigerenzer’s work suggests that some uncertainty is irreducible—and that trying to eliminate it entirely can actually harm decision quality.

Consider computer system validation decisions. Teams often struggle with determining how much testing is “enough,” leading to endless debates about edge cases and theoretical scenarios. The adaptive toolbox approach suggests developing simple rules that balance thoroughness with practical constraints:

The Satisficing Rule: Test until system functionality meets predefined acceptance criteria across critical business processes, then stop. Don’t continue testing just because more testing is theoretically possible.

The Critical Path Rule: Focus validation effort on the processes that directly impact patient safety and product quality. Treat administrative functions with less intensive validation approaches.

The Experience Rule: Leverage institutional knowledge about similar systems to guide validation scope. Don’t start every validation from scratch.

These heuristics don’t eliminate validation rigor—they channel it more effectively by recognizing that perfect validation is impossible and that attempting it can actually increase risk by delaying system implementation or consuming resources needed elsewhere.

Ecological Rationality in Regulatory Strategy

Perhaps nowhere is the adaptive toolbox more relevant than in regulatory strategy. Regulatory environments are characterized by uncertainty, incomplete information, and time pressure—exactly the conditions where fast-and-frugal heuristics excel.

Successful regulatory professionals develop intuitive responses to regulatory trends that often outperform complex compliance matrices. They recognize patterns in regulatory communications, anticipate inspector concerns, and adapt their strategies based on limited but diagnostic information.

The key insight from Gigerenzer’s work is that these intuitive responses aren’t unprofessional—they represent sophisticated pattern recognition based on evolved cognitive mechanisms. The challenge for quality organizations is to capture and systematize these insights without destroying their adaptive flexibility.

This might involve developing simple decision rules for common regulatory scenarios:

The Precedent Rule: When facing ambiguous regulatory requirements, look for relevant precedent in previous inspections or industry guidance rather than attempting exhaustive regulatory interpretation.

The Proactive Communication Rule: When regulatory risk is identified, communicate early with authorities rather than developing elaborate justification documents internally.

The Materiality Rule: Focus regulatory attention on changes that meaningfully affect product quality or patient safety rather than attempting to address every theoretical concern.

Building Adaptive Capability in Quality Organizations

Implementing Gigerenzer’s insights requires more than just teaching people about heuristics—it requires creating organizational conditions that support ecological rationality. This means:

Embracing Uncertainty: Stop pretending that perfect risk assessments are possible. Instead, develop decision-making approaches that are robust under uncertainty.

Valuing Experience: Recognize that experienced professionals’ intuitive responses often reflect sophisticated pattern recognition. Don’t automatically override professional judgment with algorithmic approaches.

Simplifying Decision Structures: Replace complex matrices and scoring systems with simple decision trees that focus on the most diagnostic factors.

Encouraging Rapid Iteration: Rather than trying to perfect decisions before implementation, develop approaches that allow rapid adjustment based on feedback.

Training Pattern Recognition: Help staff develop the pattern recognition skills that support effective heuristic decision-making.

The Subjectivity Challenge

One common objection to heuristic-based approaches is that they introduce subjectivity into risk management decisions. This concern reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of both traditional analytical methods and heuristic approaches.

Traditional risk matrices and analytical methods appear objective but are actually filled with subjective judgments: how risks are defined, how probabilities are estimated, how impacts are categorized, and how different risk dimensions are weighted. These subjective elements are simply hidden behind numerical facades.

Heuristic approaches make subjectivity explicit rather than hiding it. This transparency actually supports better risk management by forcing teams to acknowledge and discuss their value judgments rather than pretending they don’t exist.

The recent revision of ICH Q9 explicitly recognizes this challenge, noting that subjectivity cannot be eliminated from risk management but can be managed through appropriate process design. Fast-and-frugal heuristics support this goal by making decision logic transparent and teachable.

Four Essential Books by Gigerenzer

For quality professionals who want to dive deeper into this framework, here are four books by Gigerenzer to read:

1. “Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart” (1999) – This foundational work, authored with Peter Todd and the ABC Research Group, establishes the theoretical framework for the adaptive toolbox. It demonstrates through extensive research how simple heuristics can outperform complex analytical methods across diverse domains. For quality professionals, this book provides the scientific foundation for understanding why less can indeed be more in risk assessment.

2. “Gut Feelings: The Intelligence of the Unconscious” (2007) – This more accessible book explores how intuitive decision-making works and when it can be trusted. It’s particularly valuable for quality professionals who need to balance analytical rigor with practical decision-making under pressure. The book provides actionable insights for recognizing when to trust professional judgment and when more analysis is needed.

3. “Risk Savvy: How to Make Good Decisions” (2014) – This book directly addresses risk perception and management, making it immediately relevant to quality professionals. It challenges common misconceptions about risk communication and provides practical tools for making better decisions under uncertainty. The sections on medical decision-making are particularly relevant to pharmaceutical quality management.

4. “The Intelligence of Intuition” (Cambridge University Press, 2023) – Gigerenzer’s latest work directly challenges the widespread dismissal of intuitive decision-making in favor of algorithmic solutions. In this compelling analysis, he traces what he calls the “war on intuition” in social sciences, from early gendered perceptions that dismissed intuition as feminine and therefore inferior, to modern technological paternalism that argues human judgment should be replaced by perfect algorithms. For quality professionals, this book is essential reading because it demonstrates that intuition is not irrational caprice but rather “unconscious intelligence based on years of experience” that evolved specifically to handle uncertain and dynamic situations where logic and big data algorithms provide little benefit. The book provides both theoretical foundation and practical guidance for distinguishing reliable intuitive responses from wishful thinking—a crucial skill for quality professionals who must balance analytical rigor with rapid decision-making under uncertainty.

The Implementation Challenge

Understanding the adaptive toolbox conceptually is different from implementing it organizationally. Quality systems are notoriously resistant to change, particularly when that change challenges fundamental assumptions about how decisions should be made.

Successful implementation requires a gradual approach that demonstrates value rather than demanding wholesale replacement of existing methods. Consider starting with pilot applications in lower-risk areas where the benefits of simpler approaches can be demonstrated without compromising patient safety.

Phase 1: Recognition and Documentation – Begin by documenting the informal heuristics that experienced staff already use. You’ll likely find that your most effective team members already use something resembling fast-and-frugal decision trees for routine decisions.

Phase 2: Formalization and Testing – Convert informal heuristics into explicit decision rules and test them against historical decisions. This helps build confidence and identifies areas where refinement is needed.

Phase 3: Training and Standardization – Train staff on the formalized heuristics and create simple reference tools that support consistent application.

Phase 4: Continuous Adaptation – Build feedback mechanisms that allow heuristics to evolve as conditions change and new patterns emerge.

Measuring Success with Ecological Metrics

Traditional quality metrics often focus on process compliance rather than decision quality. Implementing an adaptive toolbox approach requires different measures of success.

Instead of measuring how thoroughly risk assessments are documented, consider measuring:

- Decision Speed: How quickly can teams classify and respond to different types of quality events?

- Decision Consistency: How much variability exists in how similar situations are handled?

- Resource Efficiency: What percentage of effort goes to analysis versus action?

- Adaptation Rate: How quickly do decision approaches evolve in response to new information?

- Outcome Quality: What are the actual consequences of decisions made using heuristic approaches?

These metrics align better with the goals of effective risk management: making good decisions quickly and consistently under uncertainty.

The Training Implication

If we accept that heuristic decision-making is not just inevitable but often superior, it changes how we think about quality training. Instead of teaching people to override their intuitive responses with analytical methods, we should focus on calibrating and improving their pattern recognition abilities.

This means:

- Case-Based Learning: Using historical examples to help staff recognize patterns and develop appropriate responses

- Scenario Training: Practicing decision-making under time pressure and incomplete information

- Feedback Loops: Creating systems that help staff learn from decision outcomes

- Expert Mentoring: Pairing experienced professionals with newer staff to transfer tacit knowledge

- Cross-Functional Exposure: Giving staff experience across different areas to broaden their pattern recognition base

Addressing the Regulatory Concern

One persistent concern about heuristic approaches is regulatory acceptability. Will inspectors accept fast-and-frugal decision trees in place of traditional risk matrices?

The key insight from Gigerenzer’s work is that regulators themselves use heuristics extensively in their inspection and decision-making processes. Experienced inspectors develop pattern recognition skills that allow them to quickly identify potential problems and focus their attention appropriately. They don’t systematically evaluate every aspect of a quality system—they use diagnostic shortcuts to guide their investigations.

Understanding this reality suggests that well-designed heuristic approaches may actually be more acceptable to regulators than complex but opaque analytical methods. The key is ensuring that heuristics are:

- Transparent: Decision logic should be clearly documented and explainable

- Consistent: Similar situations should be handled similarly

- Defensible: The rationale for the heuristic approach should be based on evidence and experience

- Adaptive: The approach should evolve based on feedback and changing conditions

The Integration Challenge

The adaptive toolbox shouldn’t replace all analytical methods—it should complement them within a broader risk management framework. The key is understanding when to use which approach.

Use Heuristics When:

- Time pressure is significant

- Information is incomplete and unlikely to improve quickly

- The decision context is familiar and patterns are recognizable

- The consequences of being approximately right quickly outweigh being precisely right slowly

- Resource constraints limit the feasibility of comprehensive analysis

Use Analytical Methods When:

- Stakes are extremely high and errors could have catastrophic consequences

- Time permits thorough analysis

- The decision context is novel and patterns are unclear

- Regulatory requirements explicitly demand comprehensive documentation

- Multiple stakeholders need to understand and agree on decision logic

Looking Forward

Gigerenzer’s work suggests that effective quality risk management will increasingly look like a hybrid approach that combines the best of analytical rigor with the adaptive flexibility of heuristic decision-making.

This evolution is already happening informally as quality professionals develop intuitive responses to common situations and use analytical methods primarily for novel or high-stakes decisions. The challenge is making this hybrid approach explicit and systematic rather than leaving it to individual discretion.

Future quality management systems will likely feature:

- Adaptive Decision Support: Systems that learn from historical decisions and suggest appropriate heuristics for new situations

- Context-Sensitive Approaches: Risk management methods that automatically adjust based on situational factors

- Rapid Iteration Capabilities: Systems designed for quick adjustment rather than comprehensive upfront planning

- Integrated Uncertainty Management: Approaches that explicitly acknowledge and work with uncertainty rather than trying to eliminate it

The Cultural Transformation

Perhaps the most significant challenge in implementing Gigerenzer’s insights isn’t technical—it’s cultural. Quality organizations have invested decades in building analytical capabilities and may resist approaches that appear to diminish the value of that investment.

The key to successful cultural transformation is demonstrating that heuristic approaches don’t eliminate analysis—they optimize it by focusing analytical effort where it provides the most value. This requires leadership that understands both the power and limitations of different decision-making approaches.

Organizations that successfully implement adaptive toolbox principles often find that they can:

- Make decisions faster without sacrificing quality

- Reduce analysis paralysis in routine situations

- Free up analytical resources for genuinely complex problems

- Improve decision consistency across teams

- Adapt more quickly to changing conditions

Conclusion: Embracing Bounded Rationality

Gigerenzer’s adaptive toolbox offers a path forward that embraces rather than fights the reality of human cognition. By recognizing that our brains have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for making good decisions under uncertainty, we can develop quality systems that work with rather than against our cognitive strengths.

This doesn’t mean abandoning analytical rigor—it means applying it more strategically. It means recognizing that sometimes the best decision is the one made quickly with limited information rather than the one made slowly with comprehensive analysis. It means building systems that are robust to uncertainty rather than brittle in the face of incomplete information.

Most importantly, it means acknowledging that quality professionals are not computers. They are sophisticated pattern-recognition systems that have evolved to navigate uncertainty effectively. Our quality systems should amplify rather than override these capabilities.

The adaptive toolbox isn’t just a set of decision-making tools—it’s a different way of thinking about human rationality in organizational settings. For quality professionals willing to embrace this perspective, it offers the possibility of making better decisions, faster, with less stress and more confidence.

And in an industry where patient safety depends on the quality of our decisions, that possibility is worth pursuing, one heuristic at a time.