A pre-mortem is a proactive risk management exercise that enables pharmaceutical teams to anticipate and mitigate failures before they occur. This tool can transform compliance from a reactive checklist into a strategic asset for safeguarding product quality.

Pre-Mortems in Pharmaceutical Quality Systems

In GMP environments, where deviations in drug substance purity or drug product stability can cascade into global recalls, pre-mortems provide a structured framework to challenge assumptions. For example, a team developing a monoclonal antibody might hypothesize that aggregation occurred during drug substance purification due to inadequate temperature control in bioreactors. By contrast, a tablet manufacturing team might explore why dissolution specifications failed because of inconsistent API particle size distribution. These exercises align with ICH Q9’s requirement for systematic hazard analysis and ICH Q10’s emphasis on knowledge management, forcing teams to document tacit insights about process boundaries and failure modes.

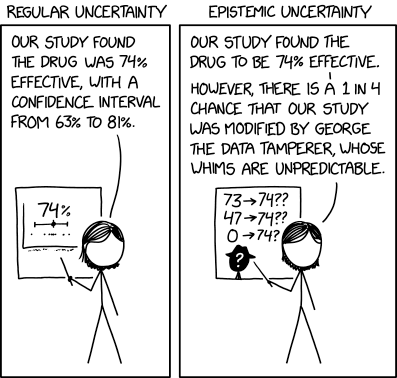

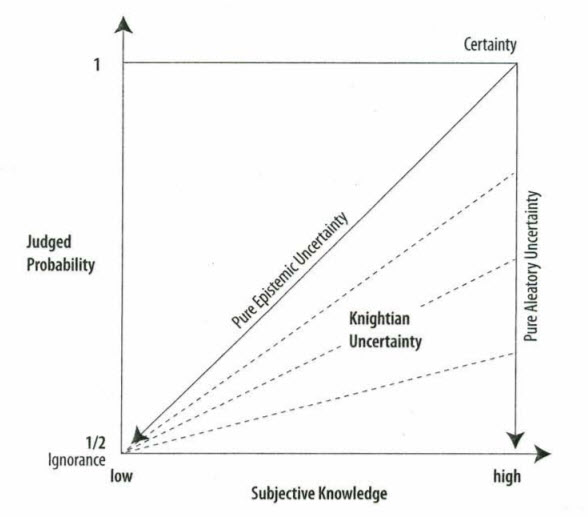

Pre-mortems excel at identifying “unknown unknowns” through creative thinking. Their value lies in uncovering risks traditional assessments miss. As a tool it can usually be strongly leveraged to identify areas for focus that may need a deeper tool, such as an FMEA. In practice, pre-mortems and FMEA are synergistic through a layered approach which satisfies ICH Q9’s requirement for both creative hazard identification and structured risk evaluation, turning hypothetical failures into validated control strategies.

By combining pre-mortems’ exploratory power with FMEA’s rigor, teams can address both systemic and technical risks, ensuring compliance while advancing operational resilience.

Implementing Pre-Mortems

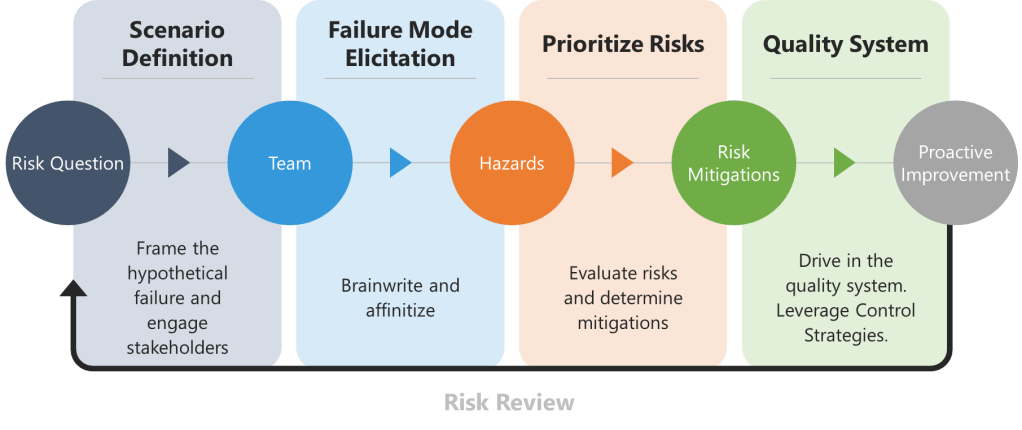

1. Scenario Definition and Stakeholder Engagement

Begin by framing the hypothetical failure, the risk question. For drug substances, this might involve declaring, “The API batch was rejected due to genotoxic impurity levels exceeding ICH M7 limits.” For drug products, consider, “Lyophilized vials failed sterility testing due to vial closure integrity breaches.” Assemble a team spanning technical operations, quality control, and regulatory affairs to ensure diverse viewpoints.

2. Failure Mode Elicitation

To overcome groupthink biases in traditional brainstorming, teams should begin with brainwriting—a silent, written idea-generation technique. The prompt is a request to list reasons behind the risk question, such as “List reasons why the API batch failed impurity specifications”. Participants anonymously write risks on structured templates for 10–15 minutes, ensuring all experts contribute equally.

The collected ideas are then synthesized into a fishbone (Ishikawa) diagram, categorizing causes relevant branches, using a 6 M technique.

This method ensures comprehensive risk identification while maintaining traceability for regulatory audits.

3. Risk Prioritization and Control Strategy Development

Risks identified during the pre-mortem are evaluated using a severity-probability-detectability matrix, structured similarly to Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA).

4. Integration into Pharmaceutical Quality Systems

Mitigation plans are formalized in in control strategies and other mechanisms.

Case Study: Preventing Drug Substance Oxidation in a Small Molecule API

A company developing an oxidation-prone API conducted a pre-mortem anticipating discoloration and potency loss. The exercise revealed:

- Drug substance risk: Inadequate nitrogen sparging during final isolation led to residual oxygen in crystallization vessels.

- Drug product risk: Blister packaging with insufficient moisture barrier exacerbated degradation.

Mitigations included installing dissolved oxygen probes in purification tanks and switching to aluminum-foil blisters with desiccants. Process validation batches showed a 90% reduction in oxidation byproducts, avoiding a potential FDA Postmarketing Commitment