On August 7, 2025, FDA Commissioner Marty Makary announced a program that, on its surface, appears to be a straightforward effort to strengthen domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing. The FDA PreCheck initiative promises “regulatory predictability” and “streamlined review” for companies building new U.S. drug manufacturing facilities. It arrives wrapped in the language of national security—reducing dependence on foreign manufacturing, securing critical supply chains, ensuring Americans have access to domestically-produced medicines.

This is the story the press release tells.

But if you read PreCheck through the lens of falsifiable quality systems a different narrative emerges. PreCheck is not merely an economic incentive program or a supply chain security measure. It is, more fundamentally, a confession.

It is the FDA admitting that the current Pre-Approval Inspection (PAI) and Pre-License Inspection (PLI) model—the high-stakes, eleventh-hour facility audit conducted weeks before the PDUFA date—is a profoundly inefficient mechanism for establishing trust. It is an acknowledgment that evaluating a facility’s “GMP compliance” only in the context of a specific product application, only after the facility is built, only when the approval clock is ticking, creates a system where failures are discovered at the moment when corrections are most expensive and most disruptive.

PreCheck proposes, instead, that the FDA should evaluate facilities earlier, more frequently, and independent of the product approval timeline. It proposes that manufacturers should be able to earn regulatory confidence in their facility design (Phase 1: Facility Readiness) before they ever file a product application, and that this confidence should carry forward into the application review (Phase 2: CMC streamlining).

This is not revolutionary. This is mostly how the European Medicines Agency (EMA) already works. This is the logic behind WHO Prequalification’s phased inspection model. This is the philosophy embedded in PIC/S risk-based inspection planning.

What is revolutionary—at least for the FDA—is the implicit admission that a manufacturing facility is not a binary state (compliant/non-compliant) evaluated at a single moment in time, but rather a developmental system that passes through stages of maturity, and that regulatory oversight should be calibrated to those stages.

This is not a cheerleading piece for PreCheck. It is an analysis of what PreCheck reveals about the epistemology of regulatory inspection, and a call for a more explicit, more testable framework for what it means for a facility to be “ready.” I also have concerns about the ability of the FDA to carry this out, and the dangers of on-going regulatory capture that I won’t really cover here.

Anatomy of PreCheck—What the Program Actually Proposes

The Two-Phase Structure

PreCheck is built on two complementary phases:

Phase 1: Facility Readiness

This phase focuses on early engagement between the manufacturer and the FDA during the facility’s design, construction, and pre-production stages. The manufacturer is encouraged—though not required, as the program is voluntary—to submit a Type V Drug Master File (DMF) containing:

- Site operations layout and description

- Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) elements

- Quality Management Maturity (QMM) practices

- Equipment specifications and process flow diagrams

This Type V DMF serves as a “living document” that can be incorporated by reference into future drug applications. The FDA will review this DMF and provide feedback on facility design, helping to identify potential compliance issues before construction is complete.

Michael Kopcha, Director of the FDA’s Office of Pharmaceutical Quality (OPQ), clarified at the September 30 public meeting that if a facility successfully completes the Facility Readiness Phase, an inspection may not be necessary when a product application is later filed.

This is the core innovation: decoupling facility assessment from product application.

Phase 2: Application Submission

Once a product application (NDA, ANDA, or BLA) is filed, the second phase focuses on streamlining the Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) section of the application. The FDA offers:

- Pre-application meetings

- Early feedback on CMC data needs

- Facility readiness and inspection planning discussions

Because the facility has already been reviewed in Phase 1, the CMC review can proceed with greater confidence that the manufacturing site is capable of producing the product as described in the application.

Importantly, Kopcha also clarified that only the CMC portion of the review is expedited—clinical and non-clinical sections follow the usual timeline. This is a critical limitation that industry stakeholders noted with some frustration, as it means PreCheck does not shorten the overall approval timeline as much as initially hoped.

What PreCheck Is Not

To understand what PreCheck offers, it is equally important to understand what it does not offer:

It is not a fast-track program. PreCheck does not provide priority review or accelerated approval pathways. It is a facility-focused engagement model, not a product-focused expedited review.

It is not a GMP certificate. Unlike the European system, where facilities can obtain a GMP certificate independent of any product application, PreCheck still requires a product application to trigger Phase 2. The Facility Readiness Phase (Phase 1) provides early engagement, but does not result in a standalone “facility approval” that can be referenced by multiple products or multiple sponsors.

It is not mandatory. PreCheck is voluntary. Manufacturers can continue to follow the traditional PAI/PLI pathway if they prefer.

It does not apply to existing facilities (yet). PreCheck is designed for new domestic manufacturing facilities. Industry stakeholders have requested expansion to include existing facility expansions and retrofits, but the FDA has not committed to this.

It does not decouple facility inspections from product approvals. Despite industry’s strong push for this—Big Pharma executives from Eli Lilly, Merck, and others explicitly requested at the public meeting that the FDA adopt the EMA model of decoupling GMP inspections from product applications—the FDA has not agreed to this. Phase 1 provides early feedback, but Phase 2 still ties the facility assessment to a specific product application.

The Type V DMF as the Backbone of PreCheck

The Type V Drug Master File is the operational mechanism through which PreCheck functions.

Historically, Type V DMFs have been a catch-all category for “FDA-accepted reference information” that doesn’t fit into the other DMF types (Type II for drug substances, Type III for packaging, Type IV for excipients). They have been used primarily for device constituent parts in combination products.

PreCheck repurposes the Type V DMF as a facility-centric repository. Instead of focusing on a material or a component, the Type V DMF in the PreCheck context contains:

- Facility design: Layouts, flow diagrams, segregation strategies

- Quality systems: Change control, deviation management, CAPA processes

- Quality Management Maturity: Evidence of advanced quality practices beyond CGMP minimum requirements

- Equipment and utilities: Specifications, qualification status, maintenance programs

The idea is that this DMF becomes a reusable asset. If a manufacturer builds a facility and completes the PreCheck Facility Readiness Phase, that facility’s Type V DMF can be referenced by multiple product applications from the same sponsor. This reduces redundant submissions and allows the FDA to build institutional knowledge about a facility over time.

However—and this is where the limitations become apparent—the Type V DMF is sponsor-specific. If the facility is a Contract Manufacturing Organization (CMO), the FDA has not clarified how the DMF ownership works or whether multiple API sponsors using the same CMO can leverage the same facility DMF. Industry stakeholders raised this as a significant concern at the public meeting, noting that CMOs account for approximately 50% of all facility-related CRLs.

The Type V DMF vs. Site Master File: Convergent Evolutions in Facility Documentation

The Type V DMF requirement in PreCheck bears a striking resemblance—and some critical differences—to the Site Master File (SMF) required under EU GMP and PIC/S guidelines. Understanding this comparison reveals both the potential of PreCheck and its limitations.

What is a Site Master File?

The Site Master File is a GMP documentation requirement in the EU, mandated under Chapter 4 of the EU GMP Guideline. PIC/S provides detailed guidance on SMF preparation in document PE 008-4. The SMF is:

- A facility-centric document prepared by the pharmaceutical manufacturer

- Typically 25-30 pages plus appendices, designed to be “readable when printed on A4 paper”

- A living document that is part of the quality management system, updated regularly (recommended every 2 years)

- Submitted to regulatory authorities to demonstrate GMP compliance and facilitate inspection planning

The purpose of the SMF is explicit: to provide regulators with a comprehensive overview of the manufacturing operations at a named site, independent of any specific product. It answers the question: “What GMP activities occur at this location?”

Required SMF Contents (per PIC/S PE 008-4 and EU guidance):

- General Information: Company name, site address, contact information, authorized manufacturing activities, manufacturing license copy

- Quality Management System: QA/QC organizational structure, key personnel qualifications, training programs, release procedures for Qualified Persons

- Personnel: Number of employees in production, QC, QA, warehousing; reporting structure

- Premises and Equipment: Site layouts, room classifications, pressure differentials, HVAC systems, major equipment lists

- Documentation: Description of documentation systems (batch records, SOPs, specifications)

- Production: Brief description of manufacturing operations, in-process controls, process validation policy

- Quality Control: QC laboratories, test methods, stability programs, reference standards

- Distribution, Complaints, and Product Recalls: Systems for handling complaints, recalls, and distribution controls

- Self-Inspection: Internal audit programs and CAPA systems

Critically, the SMF is product-agnostic. It describes the facility’s capabilities and systems, not specific product formulations or manufacturing procedures. An appendix may list the types of products manufactured (e.g., “solid oral dosage forms,” “sterile injectables”), but detailed product-specific CMC information is not included.

How the Type V DMF Differs from the Site Master File

The FDA’s Type V DMF in PreCheck serves a similar purpose but with important distinctions:

Similarities:

- Both are facility-centric documents describing site operations, quality systems, and GMP capabilities

- Both include site layouts, equipment specifications, and quality management elements

- Both are intended to facilitate regulatory review and inspection planning

- Both are living documents that can be updated as the facility changes

Critical Differences:

| Dimension | Site Master File (EU/PIC/S) | Type V DMF (FDA PreCheck) |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Status | Mandatory for EU manufacturing license | Voluntary (PreCheck is voluntary program) |

| Independence from Products | Fully independent—facility can be certified without any product application | Partially independent—Phase 1 allows early review, but Phase 2 still ties to product application |

| Ownership | Facility owner (manufacturer or CMO) | Sponsor-specific—unclear for CMO facilities with multiple clients |

| Regulatory Outcome | Can support GMP certificate or manufacturing license independent of product approvals | Does not result in standalone facility approval; only facilitates product application review |

| Scope | Describes all manufacturing operations at the site | Focused on specific facility being built, intended to support future product applications from that sponsor |

| International Recognition | Harmonized internationally—PIC/S member authorities recognize each other’s SMF-based inspections | FDA-specific—no provision for accepting EU GMP certificates or SMFs in lieu of PreCheck participation |

| Length and Detail | 25-30 pages plus appendices, designed for conciseness | No specified page limit; QMM practices component could be extensive |

The Critical Gap: Product-Specificity vs. Facility Independence

The most significant difference lies in how the documents relate to product approvals.

In the EU system, a manufacturer submits the SMF to the National Competent Authority (NCA) as part of obtaining or maintaining a manufacturing license. The NCA inspects the facility and, if compliant, grants a GMP certificate that is valid across all products manufactured at that site.

When a Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) is later filed for a specific product, the CHMP can reference the existing GMP certificate and decide whether a pre-approval inspection is needed. If the facility has been recently inspected and found compliant, no additional inspection may be required. The facility’s GMP status is decoupled from the product approval.

The FDA’s Type V DMF in PreCheck does not create this decoupling. While Phase 1 allows early FDA review of the facility design, the Type V DMF is still tied to the sponsor’s product applications. It is not a standalone “facility certificate.” Multiple products from the same sponsor can reference the same Type V DMF, but the FDA has not clarified whether:

- The DMF reduces the need for PAIs/PLIs on second, third, and subsequent products from the same facility

- The DMF serves any function outside of the PreCheck program (e.g., for routine surveillance inspections)

At the September 30 public meeting, industry stakeholders explicitly requested that the FDA adopt the EU GMP certificate model, where facilities can be certified independent of product applications. The FDA acknowledged the request but did not commit to this approach.

Confidentiality: DMFs Are Proprietary

The Type V DMF operates under FDA’s DMF confidentiality rules (21 CFR 314.420). The DMF holder (the manufacturer) authorizes the FDA to reference the DMF when reviewing a specific sponsor’s application, but the detailed contents are not disclosed to the sponsor or to other parties. This protects proprietary manufacturing information, especially important for CMOs who serve competing sponsors.

However, PreCheck asks manufacturers to include Quality Management Maturity (QMM) practices in the Type V DMF—information that goes beyond what is typically in a DMF and beyond what is required in an SMF. As discussed earlier, industry is concerned that disclosing advanced quality practices could create new regulatory expectations or vulnerabilities. This tension does not exist with SMFs, which describe only what is required by GMP, not what is aspirational.

Could the FDA Adopt a Site Master File Model?

The comparison raises an obvious question: Why doesn’t the FDA simply adopt the EU Site Master File requirement?

Several barriers exist:

1. U.S. Legal Framework

The FDA does not issue facility manufacturing licenses the way EU NCAs do. In the U.S., a facility is “approved” only in the context of a specific product application (NDA, ANDA, BLA). The FDA has establishment registration (Form FDA 2656), but registration does not constitute approval—it is merely notification that a facility exists and intends to manufacture drugs[not in sources but common knowledge].

To adopt the EU GMP certificate model, the FDA would need either:

- Statutory authority to issue facility licenses independent of product applications, or

- A regulatory framework that allows facilities to earn presumption of compliance that carries across multiple products

Neither currently exists in U.S. law.

2. FDA Resource Model

The FDA’s inspection system is application-driven. PAIs and PLIs are triggered by product applications, and the cost is implicitly borne by the applicant through user fees. A facility-centric certification system would require the FDA to conduct routine facility inspections on a 1-3 year cycle (as the EMA/PIC/S model does), independent of product filings.

This would require:

- Significant increases in FDA inspector workforce

- A new fee structure (facility fees vs. application fees)

- Coordination across CDER, CBER, and Office of Inspections and Investigations (OII)

PreCheck sidesteps this by keeping the system voluntary and sponsor-initiated. The FDA does not commit to routine re-inspections; it merely offers early engagement for new facilities.

3. CDMO Business Model Complexity

Approximately 50% of facility-related CRLs involve Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations. CDMOs manufacture products for dozens or hundreds of sponsors. In the EU, the CMO has one GMP certificate that covers all its operations, and each sponsor references that certificate in their MAAs.

In the U.S., each sponsor’s product application is reviewed independently. If the FDA were to adopt a facility certificate model, it would need to resolve:

- Who pays for the facility inspection—the CMO or the sponsors?

- How are facility compliance issues (OAIs, warning letters) communicated across sponsors?

- Can a facility certificate be revoked without blocking all pending product applications?

These are solvable problems—the EU has solved them—but they require systemic changes to the FDA’s regulatory framework.

The Path Forward: Incremental Convergence

The Type V DMF in PreCheck is a step toward the Site Master File model, but it is not yet there. For PreCheck to evolve into a true facility-centric system, the FDA would need to:

- Decouple Phase 1 (Facility Readiness) from Phase 2 (Product Application), allowing facilities to complete Phase 1 and earn a facility certificate or presumption of compliance that applies to all future products from any sponsor using that facility.

- Standardize the Type V DMF content to align with PIC/S SMF guidance, ensuring international harmonization and reducing duplicative submissions for facilities operating in multiple markets.

- Implement routine surveillance inspections (every 1-3 years) for facilities that have completed PreCheck, with inspection frequency adjusted based on compliance history (the PIC/S risk-based model). The major difference here probably would be facilities not yet engaged in commercial manufacturing.

- Enhance Participation in PIC/S inspection reliance, accepting EU GMP certificates and SMFs for facilities that have been recently inspected by PIC/S member authorities, and allowing U.S. Type V DMFs to be recognized internationally.

The industry’s message at the PreCheck public meeting was clear: adopt the EU model. Whether the FDA is willing—or able—to make that leap remains to be seen.

Quality Management Maturity (QMM): The Aspirational Component

Buried within the Type V DMF requirement is a more ambitious—and more controversial—element: Quality Management Maturity (QMM) practices.

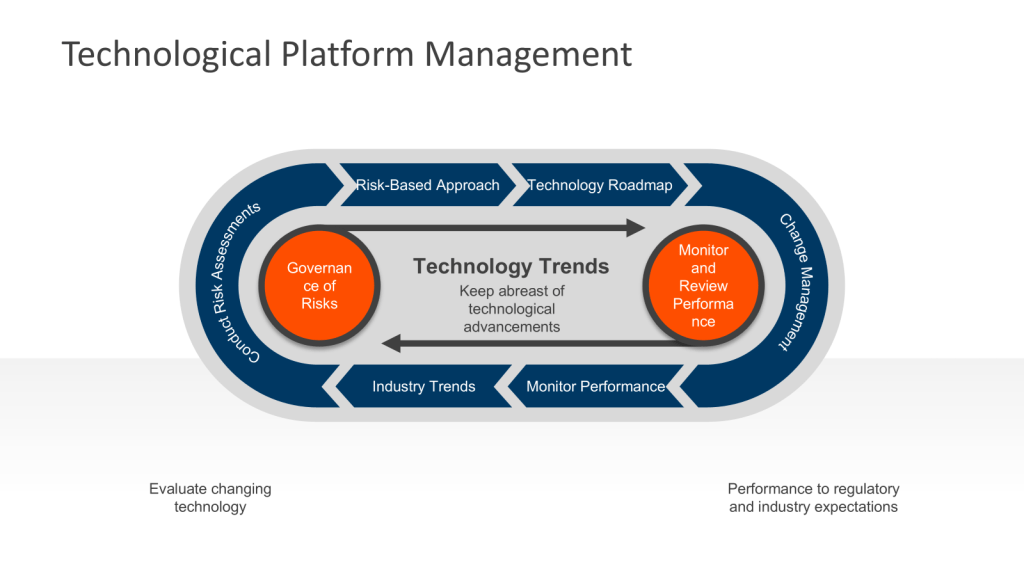

QMM is an FDA initiative (led by CDER) that aims to promote quality management practices that go beyond CGMP minimum requirements. The FDA’s QMM program evaluates manufacturers on a maturity scale across five practice areas:

- Quality Culture and Management Commitment

- Risk Management and Knowledge Management

- Data Integrity and Information Systems

- Change Management and Process Control

- Continuous Improvement and Innovation

The QMM assessment uses a pre-interview questionnaire and interactive discussion to evaluate how effectively a manufacturer monitors and manages quality. The maturity levels range from Undefined (reactive, ad hoc) to Optimized (proactive, embedded quality culture).

The FDA ran two QMM pilot programs between October 2020 and March 2022 to test this approach. The goal is to create a system where the FDA—and potentially the market—can recognize and reward manufacturers with mature quality systems that focus on continuous improvement rather than reactive compliance.

PreCheck asks manufacturers to include QMM practices in their Type V DMF. This is where the program becomes aspirational.

At the September 30 public meeting, industry stakeholders described submitting QMM information as “risky”. Why? Because QMM is not fully defined. The assessment protocol is still in development. The maturity criteria are not standardized. And most critically, manufacturers fear that disclosing information about their quality systems beyond what is required by CGMP could create new expectations or new vulnerabilities during inspections.

One attendee noted that “QMS information is difficult to package, usually viewed on inspection”. In other words, quality maturity is something you demonstrate through behavior, not something you document in a binder.

The FDA’s inclusion of QMM in PreCheck reveals a tension: the agency wants to move beyond compliance theater—beyond the checkbox mentality of “we have an SOP for that”—and toward evaluating whether manufacturers have the organizational discipline to maintain control over time. But the FDA has not yet figured out how to do this in a way that feels safe or fair to industry.

This is the same tension I discussed in my August 2025 post on “The Effectiveness Paradox“: how do you evaluate a quality system’s capability to detect its own failures, not just its ability to pass an inspection when everything is running smoothly?

The Current PAI/PLI Model and Why It Fails

To understand why PreCheck is necessary, we must first understand why the current Pre-Approval Inspection (PAI) and Pre-License Inspection (PLI) model is structurally flawed.

The High-Stakes Inspection at the Worst Possible Time

Under the current system, the FDA conducts a PAI (for drugs under CDER) or PLI (for biologics under CBER) to verify that a manufacturing facility is capable of producing the drug product as described in the application. This inspection is risk-based—the FDA does not inspect every application. But when an inspection is deemed necessary, the timing is brutal.

As one industry executive described at the PreCheck public meeting: “We brought on a new U.S. manufacturing facility two years ago and the PAI for that facility was weeks prior to our PDUFA date. At that point, we’re under a lot of pressure. Any questions or comments or observations that come up during the PAI are very difficult to resolve in that time frame”.

This is the structural flaw: the FDA evaluates the facility after the facility is built, after the application is filed, and as close as possible to the approval decision. If the inspection reveals deficiencies—data integrity failures, inadequate cleaning validation, contamination control gaps, equipment qualification issues—the manufacturer has very little time to correct them before the PDUFA clock expires.

The result? Complete Response Letters (CRLs).

The CRL Epidemic: Facility Failures Blocking Approvals

The data on inspection-related CRLs is stark.

In a 2024 analysis of BLA outcomes, researchers found that BLAs were issued CRLs nearly half the time in 2023—the highest rate ever recorded. Of these CRLs, approximately 20% were due to facility inspection failures.

Breaking this down further:

- Foreign manufacturing sites are associated with more CRs, proportionate to the number of PLIs conducted.

- Approximately 50% of facility deficiencies are for Contract Development Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs).

- Approximately 75% of Applicant-Site CRs are for biosimilars.

- The five most-cited facilities (each with ≥5 CRs) account for ~35% of all CR deficiencies.

In a separate analysis of CRL drivers from 2020–2024, Manufacturing/CMC deficiencies and Facility Inspection Failures together account for over 60% of all CRLs. This includes:

- Inadequate control of production processes

- Unstable manufacturing

- Data gaps in CMC

- GMP site inspections revealing uncontrolled processes, document gaps, hygiene issues

The pattern is clear: facility issues discovered late in the approval process are causing massive delays.

Why the Late-Stage Inspection Model Creates Failure

The PAI/PLI model creates failure for three reasons:

1. The Inspection Evaluates “Work-as-Done” When It’s Too Late to Change It

When the FDA arrives for a PAI/PLI, the facility is already built. The equipment is already installed. The processes are already validated (or supposed to be). The SOPs are already written.

If the inspector identifies a fundamental design flaw—say, inadequate segregation between manufacturing suites, or a HVAC system that cannot maintain differential pressure during interventions—the manufacturer cannot easily fix it. Redesigning cleanroom airflow or adding airlocks requires months of construction and re-qualification. The PDUFA clock does not stop.

This is analogous to the Rechon Life Science warning letter I analyzed in September 2025, where the smoke studies revealed turbulent airflow over open vials, contradicting the firm’s Contamination Control Strategy. The CCS claimed unidirectional flow protected the product. The smoke video showed eddies. But by the time this was discovered, the facility was operational, the batches were made, and the “fix” required redesigning the isolator.

2. The Inspection Creates Adversarial Pressure Instead of Collaborative Learning

Because the PAI occurs weeks before the PDUFA date, the inspection becomes a pass/fail exam rather than a learning opportunity. The manufacturer is under intense pressure to defend their systems rather than interrogate them. Questions from inspectors are perceived as threats, not invitations to improve.

This is the opposite of the falsifiable quality mindset. A falsifiable system would welcome the inspection as a chance to test whether the control strategy holds up under scrutiny. But the current timing makes this psychologically impossible. The stakes are too high.

3. The Inspection Conflates “Facility Capability” with “Product-Specific Compliance”

The PAI/PLI is nominally about verifying that the facility can manufacture the specific product in the application. But in practice, inspectors evaluate general GMP compliance—data integrity, quality unit independence, deviation investigation rigor, cleaning validation adequacy—not just product-specific manufacturing steps.

The FDA does not give “facility certificates” like the EMA does. Every product application triggers a new inspection (or waiver decision) based on the facility’s recent inspection history. This means a facility with a poor inspection outcome on one product will face heightened scrutiny on all subsequent products—creating a negative feedback loop.

Comparative Regulatory Philosophy—EMA, WHO, and PIC/S

To understand whether PreCheck is sufficient, we must compare it to how other regulatory agencies conceptualize facility oversight.

The EMA Model: Decoupling and Delegation

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) operates a decentralized inspection system. The EMA itself does not conduct inspections; instead, National Competent Authorities (NCAs) in EU member states perform GMP inspections on behalf of the EMA.

The key structural differences from the FDA:

1. Facility Inspections Are Decoupled from Product Applications

In the EU, a manufacturing facility can be inspected and receive a GMP certificate from the NCA independent of any specific product application. This certificate attests that the facility complies with EU GMP and is capable of manufacturing medicinal products according to its authorized scope.

When a Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) is filed, the CHMP (Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use) can request a GMP inspection if needed, but if the facility has a recent GMP certificate in good standing, a new inspection may not be necessary.

This means the facility’s “GMP status” is assessed separately from the product’s clinical and CMC review. Facility issues do not automatically block product approval—they are addressed through a separate remediation pathway.

2. Risk-Based and Reliance-Based Inspection Planning

The EMA employs a risk-based approach to determine inspection frequency. Facilities are inspected on a routine re-inspection program (typically every 1-3 years depending on risk), with the frequency adjusted based on:

- Previous inspection findings (critical, major, or minor deficiencies)

- Product type and patient risk

- Manufacturing complexity

- Company compliance history

Additionally, the EMA participates in PIC/S inspection reliance (discussed below), meaning it may accept inspection reports from other competent authorities without conducting its own inspection.

3. Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) with the FDA

The U.S. and EU have a Mutual Recognition Agreement for GMP inspections. Under this agreement, the FDA and EMA recognize each other’s inspection outcomes for human medicines, reducing duplicate inspections.

Importantly, the EMA has begun accepting FDA inspection reports proactively during the pre-submission phase. Applicants can provide FDA inspection reports to support their MAA, allowing the EMA to make risk-based decisions about whether an additional inspection is needed.

This is the inverse of what the FDA is attempting with PreCheck. The EMA is saying: “We trust the FDA’s inspection, so we don’t need to repeat it.” The FDA, with PreCheck, is saying: “We will inspect early, so we don’t need to repeat it later.” Both approaches aim to reduce redundancy, but the EMA’s reliance model is more mature.

WHO Prequalification: Phased Inspections and Leveraging SRAs

The WHO Prequalification (PQ) program provides an alternative model for facility assessment, particularly relevant for manufacturers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Key features:

1. Inspection Occurs During the Dossier Assessment, Not After

Unlike the FDA’s PAI (which occurs near the end of the review), WHO PQ conducts inspections within 6 months of dossier acceptance for assessment. This means the facility inspection happens in parallel with the technical review, not at the end.

If the inspection reveals deficiencies, the manufacturer submits a Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) plan, and WHO conducts a follow-up inspection within 6-9 months. The prequalification decision is not made until the inspection is closed.

This phased approach reduces the “all-or-nothing” pressure of the FDA’s late-stage PAI.

2. Routine Inspections Every 1-3 Years

Once a product is prequalified, WHO conducts routine inspections every 1-3 years to verify continued compliance. This aligns with the Continued Process Verification concept in FDA’s Stage 3 validation—the idea that a facility is not “validated forever” after one inspection, but must demonstrate ongoing control.

3. Reliance on Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRAs)

WHO PQ may leverage inspection reports from Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRAs) or WHO-Listed Authorities (WLAs). If the facility has been recently inspected by an SRA (e.g., FDA, EMA, Health Canada) and the scope is appropriate, WHO may waive the onsite inspection and rely on the SRA’s findings.

This is a trust-based model: WHO recognizes that conducting duplicate inspections wastes resources, and that a well-documented inspection by a competent authority provides sufficient assurance.

The FDA’s PreCheck program does not include this reliance mechanism. PreCheck is entirely FDA-centric—there is no provision for accepting EMA or WHO inspection reports to satisfy Phase 1 or Phase 2 requirements.

PIC/S: Risk-Based Inspection Planning and Classification

The Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) is an international framework for harmonizing GMP inspections across member authorities.

Two key PIC/S documents are relevant to this discussion:

1. PI 037-1: Risk-Based Inspection Planning

PIC/S provides a qualitative risk management tool to help inspectorates prioritize inspections. The model assigns each facility a risk rating (A, B, or C) based on:

- Intrinsic Risk: Product type, complexity, patient population

- Compliance Risk: Previous inspection outcomes, deficiency history

The risk rating determines inspection frequency:

- A (Low Risk): Reduced frequency (2-3 years)

- B (Moderate Risk): Moderate frequency (1-2 years)

- C (High Risk): Increased frequency (<1 year, potentially multiple times per year)

Critically, PIC/S assumes that every manufacturer will be inspected at least once within the defined period. There is no such thing as “perpetual approval” based on one inspection.

2. PI 048-1: GMP Inspection Reliance

PIC/S introduced a guidance on inspection reliance in 2018. This guidance provides a framework for desktop assessment of GMP compliance based on the inspection activities of other competent authorities.

The key principle: if another PIC/S member authority has recently inspected a facility and found it compliant, a second authority may accept that finding without conducting its own inspection.

This reliance is conditional—the accepting authority must verify that:

- The scope of the original inspection covers the relevant products and activities

- The original inspection was recent (typically within 2-3 years)

- The original authority is a trusted PIC/S member

- There have been no significant changes or adverse events since the inspection

This is the most mature version of the trust-based inspection model. It recognizes that GMP compliance is not a static state that can be certified once, but also that redundant inspections by multiple authorities waste resources and delay market access.

Comparative Summary

| Dimension | FDA (Current PAI/PLI) | FDA PreCheck (Proposed) | EMA/EU | WHO PQ | PIC/S Framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of Inspection | Late (near PDUFA) | Early (design phase) + Late (application) | Variable, risk-based | Early (during assessment) | Risk-based (1-3 years) |

| Facility vs. Product Focus | Product-specific | Facility (Phase 1) → Product (Phase 2) | Facility-centric (GMP certificate) | Product-specific with facility focus | Facility-centric |

| Decoupling | No | Partial (Phase 1 early feedback) | Yes (GMP certificate independent) | No, but phased | Yes (risk-based frequency) |

| Reliance on Other Authorities | No | No | Yes (MRA, PIC/S) | Yes (SRA reliance) | Yes (core principle) |

| Frequency | Per-application | Phase 1 (once) → Phase 2 (per-application) | Routine re-inspection (1-3 years) | Routine (1-3 years) | Risk-based (A/B/C) |

| Consequence of Failure | CRL, approval blocked | Phase 1: design guidance; Phase 2: potential CRL | CAPA, may not block approval | CAPA, follow-up inspection | Remediation, increased frequency |

The striking pattern: the FDA is the outlier. Every other major regulatory system has moved toward:

- Decoupling facility inspections from product applications

- Risk-based, routine inspection frequencies

- Reliance mechanisms to avoid duplicate inspections

- Facility-centric GMP certificates or equivalent

PreCheck is the FDA’s first step toward this model, but it is not yet there. Phase 1 provides early engagement, but Phase 2 still ties facility assessment to a specific product. PreCheck does not create a standalone “facility approval” that can be referenced across products or shared among CMO clients.

Potential Benefits of PreCheck (When It Works)

Despite its limitations, PreCheck could offer potential real benefits over the status quo—if it is implemented effectively.

Benefit 1: Early Detection of Facility Design Flaws

The most obvious benefit of PreCheck is that it allows the FDA to review facility design during construction, rather than after the facility is operational.

As one industry expert noted at the public meeting: “You’re going to be able to solve facility issues months, even years before they occur”.

Consider the alternative. Under the current PAI/PLI model, if the FDA inspector discovers during a pre-approval inspection that the cleanroom differential pressure cannot be maintained during material transfer, the manufacturer faces a choice:

- Redesign the HVAC system (months of construction, re-commissioning, re-qualification)

- Withdraw the application

- Argue that the deficiency is not critical and hope the FDA agrees

All of these options are expensive and delay the product launch.

PreCheck, by contrast, allows the FDA to flag this issue during the design review (Phase 1), when the HVAC system is still on the engineering drawings. The manufacturer can adjust the design before pouring concrete.

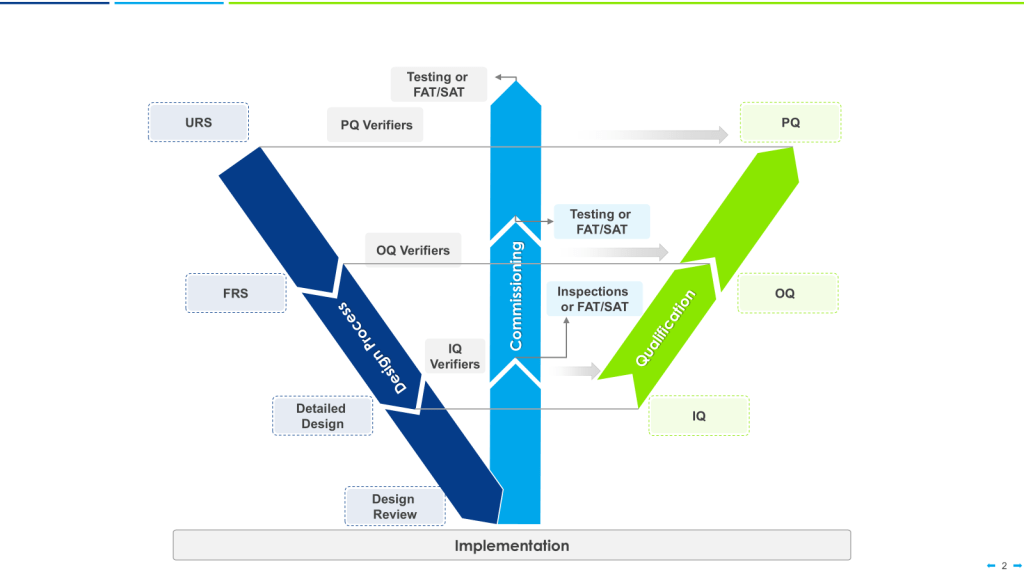

This is the principle of Design Qualification (DQ) applied to the regulatory inspection timeline. Just as equipment must pass DQ before moving to Installation Qualification (IQ), the facility should pass regulatory design review before moving to construction and operation.

Benefit 2: Reduced Uncertainty and More Predictable Timelines

The current PAI/PLI system creates uncertainty about whether an inspection will be scheduled, when it will occur, and what the outcome will be.

Manufacturers described this uncertainty as one of the biggest pain points at the PreCheck public meeting. One executive noted that PAIs are often scheduled with short notice, and manufacturers struggle to align their production schedules (especially for seasonal products like vaccines) with the FDA’s inspection availability.

PreCheck introduces structure to this chaos. If a manufacturer completes Phase 1 successfully, the FDA has already reviewed the facility and provided feedback. The manufacturer knows what the FDA expects. When Phase 2 begins (the product application), the CMC review can proceed with greater confidence that facility issues will not derail the approval.

This does not eliminate uncertainty entirely—Phase 2 still involves an inspection (or inspection waiver decision), and deficiencies can still result in CRLs. But it shifts the uncertainty earlier in the process, when corrections are cheaper.

Benefit 3: Building Institutional Knowledge at the FDA

One underappreciated benefit of PreCheck is that it allows the FDA to build institutional knowledge about a manufacturer’s quality systems over time.

Under the current model, a PAI inspector arrives at a facility for 5-10 days, reviews documents, observes operations, and leaves. The inspection report is filed. If the same facility files a second product application two years later, a different inspector may conduct the PAI, and the process starts from scratch.

The PreCheck Type V DMF, by contrast, is a living document that accumulates information about the facility over its lifecycle. The FDA reviewers who participate in Phase 1 (design review) can provide continuity into Phase 2 (application review) and potentially into post-approval surveillance.

This is the principle behind the EMA’s GMP certificate model: once the facility is certified, subsequent inspections build on the previous findings rather than starting from zero.

Industry stakeholders explicitly requested this continuity at the PreCheck meeting, asking the FDA to “keep the same reviewers in place as the process progresses”. The implication: trust is built through relationships and institutional memory, not one-off inspections.

Benefit 4: Incentivizing Quality Management Maturity

By including Quality Management Maturity (QMM) practices in the Type V DMF, PreCheck encourages manufacturers to invest in advanced quality systems beyond CGMP minimums.

This is aspirational, not transactional. The FDA is not offering faster approvals or reduced inspection frequency in exchange for QMM participation—at least not yet. But the long-term vision is that manufacturers with mature quality systems will be recognized as lower-risk, and this recognition could translate into regulatory flexibility (e.g., fewer post-approval inspections, faster review of post-approval changes).

This aligns with the philosophy I have argued for throughout 2025: a quality system should not be judged by its compliance on the day of the inspection, but by its ability to detect and correct failures over time. A mature quality system is one that is designed to falsify its own assumptions—to seek out the cracks before they become catastrophic failures.

The QMM framework is the FDA’s attempt to operationalize this philosophy. Whether it succeeds depends on whether the FDA can develop a fair, transparent, and non-punitive assessment protocol—something industry is deeply skeptical about.

Challenges and Industry Concerns

The September 30, 2025 public meeting revealed that while industry welcomes PreCheck, the program as proposed has significant gaps.

Challenge 1: PreCheck Does Not Decouple Facility Inspections from Product Approvals

The single most consistent request from industry was: decouple GMP facility inspections from product applications.

Executives from Eli Lilly, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and others explicitly called for the FDA to adopt the EMA model, where a facility can be inspected and certified independent of a product application, and that certification can be referenced by multiple products.

Why does this matter? Because under the current system (and under PreCheck as proposed), if a facility has a compliance issue, all product applications relying on that facility are at risk.

Consider a CMO that manufactures API for 10 different sponsors. If the CMO fails a PAI for one sponsor’s product, the FDA may place the entire facility under heightened scrutiny, delaying approvals for all 10 sponsors. This creates a cascade failure where one product’s facility issue blocks the market access of unrelated products.

The EMA’s GMP certificate model avoids this by treating the facility as a separate regulatory entity. If the facility has compliance issues, the NCA works with the facility to remediate them independent of pending product applications. The product approvals may be delayed, but the remediation pathway is separate.

The FDA’s Michael Kopcha acknowledged the request but did not commit: “Decoupling, streamlining, and more up-front communication is helpful… We will have to think about how to go about managing and broadening the scope”.

Challenge 2: PreCheck Only Applies to New Facilities, Not Existing Ones

PreCheck is designed for new domestic manufacturing facilities. But the majority of facility-related CRLs involve existing facilities—either because they are making post-approval changes, transferring manufacturing sites, or adding new products.

Industry stakeholders requested that PreCheck be expanded to include:

- Existing facility expansions and retrofits

- Post-approval changes (e.g., adding a new production line, changing a manufacturing process)

- Site transfers (moving production from one facility to another)

The FDA did not commit to this expansion, but Kopcha noted that the agency is “thinking about how to broaden the scope”.

The challenge here is that the FDA lacks a facility lifecycle management framework. The current system treats each product application as a discrete event, with no mechanism for a facility to earn cumulative credit for good performance across multiple products over time.

This is what the PIC/S risk-based inspection model provides: a facility with a strong compliance history moves to reduced inspection frequency (e.g., every 3 years instead of annually). A facility with a poor history moves to increased frequency (e.g., multiple inspections per year). The inspection burden is proportional to risk.

PreCheck Phase 1 could serve this function—if it were expanded to existing facilities. A CMO that completes Phase 1 and demonstrates mature quality systems could earn presumption of compliance for future product applications, reducing the need for repeated PAIs/PLIs.

But as currently designed, PreCheck is a one-time benefit for new facilities only.

Challenge 3: Confidentiality and Intellectual Property Concerns

Manufacturers expressed significant concern about what information the FDA will require in the Type V DMF and whether that information will be protected from Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.

The concern is twofold:

1. Proprietary Manufacturing Details

The Type V DMF is supposed to include facility layouts, equipment specifications, and process flow diagrams. For some manufacturers—especially those with novel technologies or proprietary processes—this information is competitively sensitive.

If the DMF is subject to FOIA disclosure (even with redactions), competitors could potentially reverse-engineer the manufacturing strategy.

2. CDMO Relationships

For Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs), the Type V DMF creates a dilemma. The CDMO owns the facility, but the sponsor owns the product. Who submits the DMF? Who controls access to it? If multiple sponsors use the same CDMO facility, can they all reference the same DMF, or must each sponsor submit a separate one?

Industry requested clarity on these ownership and confidentiality issues, but the FDA has not yet provided detailed guidance.

This is not a trivial concern. Approximately 50% of facility-related CRLs involve CDMOs. If PreCheck cannot accommodate the CDMO business model, its utility is limited.

The Confidentiality Paradox: Good for Companies, Uncertain for Consumers

The confidentiality protections embedded in the DMF system—and by extension, in PreCheck’s Type V DMF—serve a legitimate commercial purpose. They allow manufacturers to protect proprietary manufacturing processes, equipment specifications, and quality system innovations from competitors. This protection is particularly critical for Contract Manufacturing Organizations (CMOs) who serve multiple competing sponsors and cannot afford to have one client’s proprietary methods disclosed to another.

But there is a tension here that deserves explicit acknowledgment: confidentiality rules that benefit companies are not necessarily optimal for consumers. This is not an argument for eliminating trade secret protections—innovation requires some degree of secrecy. Rather, it is a call to examine where the balance is struck and whether current confidentiality practices are serving the public interest as robustly as they serve commercial interests.

What Confidentiality Hides from Public View

Under current FDA confidentiality rules (21 CFR 314.420 for DMFs, and broader FOIA exemptions for commercial information), the following categories of information are routinely shielded from public disclosure.

The detailed manufacturing procedures, equipment specifications, and process parameters submitted in Type II DMFs (drug substances) and Type V DMFs (facilities) are never disclosed to the public. They may not even be disclosed to the sponsor referencing the DMF—only the FDA reviews them.

This means that if a manufacturer is using a novel but potentially risky manufacturing technique—say, a continuous manufacturing process that has not been validated at scale, or a cleaning procedure that is marginally effective—the public has no way to know. The FDA reviews this information, but the public cannot verify the FDA’s judgment.

2. Drug Pricing Data and Financial Arrangements

Pharmaceutical companies have successfully invoked trade secret protections to keep drug prices, manufacturing costs, and financial arrangements (rebates, discounts) confidential. In the United States, transparency laws requiring companies to disclose drug pricing information have faced constitutional challenges on the grounds that such disclosure constitutes an uncompensated “taking” of trade secrets.

This opacity prevents consumers, researchers, and policymakers from understanding why drugs cost what they cost and whether those prices are justified by manufacturing expenses or are primarily driven by monopoly pricing.

3. Manufacturing Deficiencies and Inspection Findings

When the FDA conducts an inspection and issues a Form FDA 483 (Inspectional Observations), those observations are eventually made public. But the detailed underlying evidence—the batch records showing failures, the deviations that were investigated, the CAPA plans that were proposed—remain confidential as part of the company’s internal quality records.

This means the public can see that a deficiency occurred, but cannot assess how serious it was or whether the corrective action was adequate. We are asked to trust that the FDA’s judgment was sound, without access to the data that informed that judgment.

The Public Interest Argument for Greater Transparency

The case for reducing confidentiality protections—or at least creating exceptions for public health—rests on several arguments:

Argument 1: The Public Funds Drug Development

As health law scholars have noted, the public makes extraordinary investments in private companies’ drug research and development through NIH grants, tax incentives, and government contracts. Yet details of clinical trial data, manufacturing processes, and government contracts often remain secret, even though the public paid for the research.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine contract explicitly allowed the company to keep secret “production/manufacturing know-how, trade secrets, [and] clinical data,” despite massive public funding of the vaccine’s development. European Commission vaccine contracts similarly included generous redactions of price per dose, amounts paid up front, and rollout schedules.

If the public is paying for innovation, the argument goes, the public should have access to the results.

Argument 2: Regulators Are Understaffed and Sometimes Wrong

The FDA is chronically understaffed and under pressure to approve medicines quickly. Regulators sometimes make mistakes. Without access to the underlying data—manufacturing details, clinical trial results, safety signals—independent researchers cannot verify the FDA’s conclusions or identify errors that might not be apparent to a time-pressured reviewer.

Clinical trial transparency advocates argue that summary-level data, study protocols, and even individual participant data can be shared in ways that protect patient privacy (through anonymization and redaction) while allowing independent verification of safety and efficacy claims.

The same logic applies to manufacturing data. If a facility has chronic contamination control issues, or a process validation that barely meets specifications, should that information remain confidential? Or should researchers, patient advocates, and public health officials have access to assess whether the FDA’s acceptance of the facility was reasonable?

Argument 3: Trade Secret Claims Are Often Overbroad

Legal scholars studying pharmaceutical trade secrecy have documented that companies often claim trade secret protection for information that does not meet the legal definition of a trade secret.

For example, “naked price” information—the actual price a company charges for a drug—has been claimed as a trade secret to prevent regulatory disclosure, even though such information provides minimal competitive advantage and is of significant public interest. Courts have begun to push back on these claims, recognizing that the public interest in transparency can outweigh the commercial interest in secrecy, especially in highly regulated industries like pharmaceuticals.

The concern is that companies use trade secret law strategically to suppress unwanted regulation, transparency, and competition—not to protect genuine innovations.

Argument 4: Secrecy Delays Generic Competition

Even after patent and data exclusivity periods expire, trade secret protections allow pharmaceutical companies to keep the precise composition or manufacturing process for medications confidential. This slows the release of generic competitors by preventing them from relying on existing engineering and manufacturing data.

For complex biologics, this problem is particularly acute. Biosimilar developers must reverse-engineer the manufacturing process without access to the originator’s process data, leading to delays of many years and higher costs.

If manufacturing data were disclosed after a defined exclusivity period—say, 10 years—generic and biosimilar developers could bring competition to market faster, reducing drug prices for consumers.

The Counter-Argument: Why Companies Need Confidentiality

It is important to acknowledge the legitimate reasons why confidentiality protections exist:

1. Protecting Innovation Incentives

If manufacturing processes were disclosed, competitors could immediately copy them, undermining the innovator’s investment in developing the process. This would reduce incentives for process innovation and potentially slow the development of more efficient, higher-quality manufacturing methods.

2. Preventing Misuse of Information

Detailed manufacturing data could, in theory, be used by bad actors to produce counterfeit drugs or to identify vulnerabilities in the supply chain. Confidentiality reduces these risks.

3. Maintaining Competitive Differentiation

For CMOs in particular, their manufacturing expertise is their product. If their processes were disclosed, they would lose competitive advantage and potentially business. This could consolidate the industry and reduce competition among manufacturers.

4. Protecting Collaborations

The DMF system enables collaborations between API suppliers, excipient manufacturers, and drug sponsors precisely because each party can protect its proprietary information. If all information had to be disclosed, vertical integration would increase (companies would manufacture everything in-house to avoid disclosure), reducing specialization and efficiency.

Where Should the Balance Be?

The tension is real, and there is no simple resolution. But several principles might guide a more consumer-protective approach to confidentiality:

Principle 1: Time-Limited Secrecy

Trade secrets currently have no expiration date—they can remain secret indefinitely, as long as they remain non-public. But public health interests might be better served by time-limited confidentiality. After a defined period (e.g., 10-15 years post-approval), manufacturing data could be disclosed to facilitate generic/biosimilar competition.

Principle 2: Public Interest Exceptions

Confidentiality rules should include explicit public health exceptions that allow disclosure when there is a compelling public interest—for example, during pandemics, public health emergencies, or when safety signals emerge. Oregon’s drug pricing transparency law includes such an exception: trade secrets are protected unless the public interest requires disclosure.

Principle 3: Independent Verification Rights

Researchers, patient advocates, and public health officials should have structured access to clinical trial data, manufacturing data, and inspection findings under conditions that protect commercial confidentiality (e.g., through data use agreements, anonymization, secure research environments). The goal is not to publish trade secrets on the internet, but to enable independent verification of regulatory decisions.

The FDA already does this in limited ways—for example, by allowing outside experts to review confidential data during advisory committee meetings under non-disclosure agreements. This model could be expanded.

Principle 4: Narrow Trade Secret Claims

Courts and regulators should scrutinize trade secret claims more carefully, rejecting overbroad claims that seek to suppress transparency without protecting genuine innovation. “Naked price” information, aggregate safety data, and high-level manufacturing principles should not qualify for trade secret protection, even if detailed process parameters do.

Implications for PreCheck

In the context of PreCheck, the confidentiality tension manifests in several ways:

For Type V DMFs: The facility information submitted in Phase 1—site layouts, quality systems, QMM practices—will be reviewed by the FDA but not disclosed to the public or even to other sponsors using the same CMO. If a facility has marginal quality practices but passes PreCheck Phase 1, the public will never know. We are asked to trust the FDA’s judgment without transparency into what was reviewed or what deficiencies (if any) were identified.

For QMM Disclosure: Industry is concerned that submitting Quality Management Maturity information is “risky” because it discloses advanced practices beyond CGMP requirements. But the flip side is: if manufacturers are not willing to disclose their quality practices, how can regulators—or the public—assess whether those practices are adequate?

QMM is supposed to reward transparency and maturity. But if the information remains confidential and is never subjected to independent scrutiny, it becomes another form of compliance theater—a document that the FDA reviews in secret, with no external verification.

For Inspection Reliance: If the FDA begins accepting EMA GMP certificates or PIC/S inspection reports (as industry has requested), will those international inspection findings be more transparent than U.S. inspections? In some jurisdictions, yes—the EU publishes more detailed inspection outcomes than the FDA does. But in other jurisdictions, confidentiality practices may be even more restrictive.

A Tension Worth Monitoring

I do not claim to have resolved this tension. Reasonable people can disagree on where the line should be drawn between protecting innovation and ensuring public accountability.

But what I will argue is this: the tension deserves ongoing attention. As PreCheck evolves, as QMM assessments become more detailed, as Type V DMFs accumulate facility data over years—we should ask, repeatedly:

- Who benefits from confidentiality, and who bears the risk?

- Are there ways to enable independent verification without destroying commercial incentives?

- Is the FDA using its discretion to share data proactively, or defaulting to secrecy when transparency might serve the public interest?

The history of pharmaceutical regulation is, in part, a history of secrets revealed too late. Vioxx’s cardiovascular risks. Thalidomide’s teratogenicity. OxyContin’s addictiveness. In each case, information that was known or knowable earlier remained hidden—sometimes due to fraud, sometimes due to regulatory caution, sometimes due to confidentiality rules that prioritized commercial interests over public health.

PreCheck, if it succeeds, will create a new repository of confidential facility data held by the FDA. That data could be a public asset—enabling faster approvals, better-informed regulatory decisions, earlier detection of quality problems. Or it could become another black box, where the public is asked to trust that the system works without access to the evidence.

The choice is not inevitable. It is a design decision—one that regulators, legislators, and industry will make, explicitly or implicitly, in the years ahead.

We should make it explicitly, with full awareness of whose interests are being prioritized and what risks are being accepted on behalf of patients who have no seat at the table.

Challenge 4: QMM is Not Fully Defined, and Submission Feels “Risky”

As discussed earlier, manufacturers are wary of submitting Quality Management Maturity (QMM) information because the assessment framework is not fully developed.

One attendee at the public meeting described QMM submission as “risky” because:

- The FDA has not published the final QMM assessment protocol

- The maturity criteria are subjective and open to interpretation

- Disclosing quality practices beyond CGMP requirements could create new expectations that the manufacturer must meet

The analogy is this: if you tell the FDA, “We use statistical process control to detect process drift in real-time,” the FDA might respond, “Great! Show us your SPC data for the last two years.” If that data reveals a trend that the manufacturer considered acceptable but the FDA considers concerning, the manufacturer has created a problem by disclosing the information.

This is the opposite of the trust-building that QMM is supposed to enable. Instead of rewarding manufacturers for advanced quality practices, the program risks punishing them for transparency.

Until the FDA clarifies that QMM participation is non-punitive and that disclosure of advanced practices will not trigger heightened scrutiny, industry will remain reluctant to engage fully with this component of PreCheck.

Challenge 5: Resource Constraints—Will PreCheck Starve Other FDA Programs?

Industry stakeholders raised a practical concern: if the FDA dedicates inspectors and reviewers to PreCheck, will that reduce resources for routine surveillance inspections, post-approval change reviews, and other critical programs?

The FDA has not provided a detailed resource plan for PreCheck. The program is described as voluntary, which implies it is additive to existing workload, not a replacement for existing activities.

But inspectors and reviewers are finite resources. If PreCheck becomes popular (which the FDA hopes it will), the agency will need to either:

- Hire additional staff to support PreCheck (requiring Congressional appropriations)

- Deprioritize other inspection activities (e.g., routine surveillance)

- Limit the number of PreCheck engagements per year (creating a bottleneck)

One industry representative noted that the economic incentives for domestic manufacturing are weak—it takes 5-7 years to build a new plant, and generic drug margins are thin. Unless the FDA can demonstrate that PreCheck provides substantial time and cost savings, manufacturers may not participate at the scale needed to meet the program’s supply chain security goals.

The CRL Crisis—How Facility Deficiencies Are Blocking Approvals

To understand the urgency of PreCheck, we must examine the data on inspection-related Complete Response Letters (CRLs).

The Numbers: CRLs Are Rising, Facility Issues Are a Leading Cause

In 2023, BLAs were issued CRLs nearly half the time—an unprecedented rate. This represents a sharp increase from previous years, driven by multiple factors:

- More BLA submissions overall (especially biosimilars under the 351(k) pathway)

- Increased scrutiny of manufacturing and CMC sections

- More for-cause inspections (up 250% in 2025 compared to historical baseline)

Of the CRLs issued in 2023-2024, approximately 20% were due to facility inspection failures. This makes facility issues the third most common CRL driver, behind Manufacturing/CMC deficiencies (44%) and Clinical Evidence Gaps (44%).

Breaking down the facility-related CRLs:

- Foreign manufacturing sites are associated with more CRLs proportionate to the number of PLIs conducted

- 50% of facility deficiencies involve Contract Manufacturing Organizations (CMOs)

- 75% of Applicant-Site CRs are for biosimilar applications

- The five most-cited facilities account for ~35% of CR deficiencies

This last statistic is revealing: the CRL problem is concentrated among a small number of repeat offenders. These facilities receive CRLs on multiple products, suggesting systemic quality issues that are not being resolved between applications.

What Deficiencies Are Causing CRLs?

Analysis of FDA 483 observations and warning letters from FY2024 reveals the top inspection findings driving CRLs:

- Data Integrity Failures (most common)

- ALCOA+ principles not followed

- Inadequate audit trails

- 21 CFR Part 11 non-compliance

- Quality Unit Failures

- Inadequate oversight

- Poor release decisions

- Ineffective CAPA systems

- Superficial root cause analysis

- Inadequate Process/Equipment Qualification

- Equipment not qualified before use

- Process validation protocols deficient

- Continued Process Verification not implemented

- Contamination Control and Environmental Monitoring Issues

- Inadequate monitoring locations (the “representative” trap discussed in my Rechon and LeMaitre analyses)

- Failure to investigate excursions

- Contamination Control Strategy not followed

- Stability Program Deficiencies

- Incomplete stability testing

- Data does not support claimed shelf-life

These findings are not product-specific. They are systemic quality system failures that affect the facility’s ability to manufacture any product reliably.

This is the fundamental problem with the current PAI/PLI model: the FDA discovers general GMP deficiencies during a product-specific inspection, and those deficiencies block approval even though they are not unique to that product.

The Cascade Effect: One Facility Failure Blocks Multiple Approvals

The data on repeat offenders is particularly troubling. Facilities with ≥3 CRs are primarily biosimilar manufacturers or CMOs.

This creates a cascade: a CMO fails a PLI for Product A. The FDA places the CMO on heightened surveillance. Products B, C, and D—all unrelated to Product A—face delayed PAIs because the FDA prioritizes re-inspecting the CMO to verify corrective actions. By the time Products B, C, and D reach their PDUFA dates, the CMO still has not cleared the OAI classification, and all three products receive CRLs.

This is the opposite of a risk-based system. Products B, C, and D are being held hostage by Product A’s facility issues, even though the manufacturing processes are different and the sponsors are different.

The EMA’s decoupled model avoids this by treating the facility as a separate remediation pathway. If the CMO has GMP issues, the NCA works with the CMO to fix them. Product applications proceed on their own timeline. If the facility is not compliant, products cannot be approved, but the remediation does not block the application review.

For-Cause Inspections: The FDA Is Catching More Failures

One contributing factor to the rise in CRLs is the sharp increase in for-cause inspections.

In 2025, the FDA conducted for-cause inspections at nearly 25% of all inspection events, up from the historical baseline of ~10%. For-cause inspections are triggered by:

- Consumer complaints

- Post-market safety signals (Field Alert Reports, adverse event reports)

- Product recalls or field alerts

- Prior OAI inspections or warning letters

For-cause inspections have a 33.5% OAI rate—5.6 times higher than routine inspections. And approximately 50% of OAI classifications lead to a warning letter or import alert.

This suggests that the FDA is increasingly detecting facilities with serious compliance issues that were not evident during prior routine inspections. These facilities are then subjected to heightened scrutiny, and their pending product applications face CRLs.

The problem: for-cause inspections are reactive. They occur after a failure has already reached the market (a recall, a complaint, a safety signal). By that point, patient harm may have already occurred.

PreCheck is, in theory, a proactive alternative. By evaluating facilities early (Phase 1), the FDA can identify systemic quality issues before the facility begins commercial manufacturing. But PreCheck only applies to new facilities. It does not solve the problem of existing facilities with poor compliance histories.

A Framework for Site Readiness—In Place, In Use, In Control

The current PAI/PLI model treats site readiness as a binary: the facility is either “compliant” or “not compliant” at a single moment in time.

PreCheck introduces a two-phase model, separating facility design review (Phase 1) from product-specific review (Phase 2).

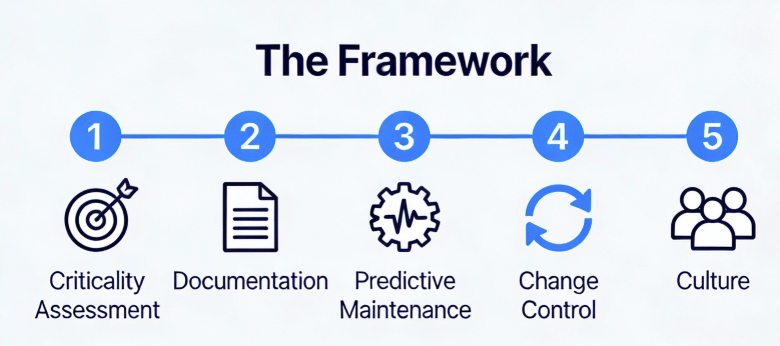

But I propose that a more useful—and more falsifiable—framework for site readiness is three-stage:

- In Place: Systems, procedures, equipment, and documentation exist and meet design specifications.

- In Use: Systems and procedures are actively implemented in routine operations as designed.

- In Control: Systems maintain validated state through continuous verification, trend analysis, and proactive improvement.

This framework maps directly onto:

- The FDA’s process validation lifecycle (Stage 1: Process Design = In Place; Stage 2: Process Qualification = In Use; Stage 3: Continued Process Verification = In Control)

- The ISPE/EU Annex 15 qualification stages (DQ/IQ = In Place; OQ/PQ = In Use; Ongoing monitoring = In Control)

- The ICH Q10 “state of control” concept (In Control)

The advantage of this framework is that it explicitly separates three distinct questions that are often conflated:

- Does the system exist? (In Place)

- Is the system being used? (In Use)

- Is the system working? (In Control)

A facility can be “In Place” without being “In Use” (e.g., SOPs are written but operators are not trained). A facility can be “In Use” without being “In Control” (e.g., operators follow procedures, but the process produces high variability and frequent deviations).

Let me define each stage in detail.

Stage 1: In Place (Structural Readiness)

Definition: Systems, procedures, equipment, and documentation exist and meet design specifications.

This is the output of Design Qualification (DQ) and Installation Qualification (IQ). It answers the question: “Has the facility been designed and built according to GMP requirements?”

Key Elements:

- Facility layout meets User Requirements Specification (URS) and regulatory expectations

- Equipment installed per manufacturer specifications

- SOPs written and approved

- Quality systems documented (change control, deviation management, CAPA, training)

- Utilities qualified (HVAC, water systems, compressed air, clean steam)

- Cleaning and sanitation programs established

- Environmental monitoring plan defined

- Personnel hired and organizational chart defined

Assessment Methods:

- Document review (URS, design specifications, as-built drawings)

- Equipment calibration certificates

- SOP index review

- Site Master File review

- Validation Master Plan review

Alignment with PreCheck: This is what Phase 1 (Facility Readiness) evaluates. The Type V DMF submitted during Phase 1 contains evidence that systems are In Place.

Alignment with EMA: This corresponds to the initial GMP inspection conducted by the NCA before granting a manufacturing license.

Inspection Outcome: If a facility is “In Place,” it means the infrastructure exists. But it says nothing about whether the infrastructure is functional or effective.

Stage 2: In Use (Operational Readiness)

Definition: Systems and procedures are actively implemented in routine operations as designed.

This is the output Validation. It answers the question: “Can the facility execute its processes reliably?”

Key Elements:

- Equipment operates within qualified parameters during production

- Personnel trained and demonstrate competency

- Process consistently produces batches meeting specifications

- Environmental monitoring executing according to contamination control strategy and generating data

- Quality systems actively used (deviations documented, investigations completed, CAPA plans implemented)

- Data integrity controls functioning (audit trails enabled, electronic records secure)

- Work-as-Done matches Work-as-Imagined

Assessment Methods:

- Observation of operations

- Review of batch records and deviations

- Interviews with operators and otherstaff

- Trending of process data (yields, cycle times, in-process controls)

- Audit of training records and competency assessments

- Inspection of actual manufacturing runs (not simulations)

Alignment with PreCheck: This is what Phase 2 (Application Submission) evaluates, particularly during the PAI/PLI (if one is conducted). The FDA inspector observes operations, reviews batch records, and verifies that the process described in the CMC section is actually being executed.

Alignment with EMA: This corresponds to the pre-approval GMP inspection requested by the CHMP if the facility has not been recently inspected.

Inspection Outcome: If a facility is “In Use,” it means the systems are functional. But it does not guarantee that the systems will remain functional over time or that the organization can detect and correct drift.

Stage 3: In Control (Sustained Performance)

Definition: Systems maintain validated state through continuous verification, trend analysis, and proactive improvement.

This is the output of Stage 3 Process Validation (Continued Process Verification). It answers the question: “Does the facility have the organizational discipline to sustain compliance?”

Key Elements:

- Statistical process control (SPC) implemented to detect trends and shifts

- Routine monitoring identifies drift before it becomes deviation

- Root cause analysis is rigorous and identifies systemic issues, not just proximate causes

- CAPA effectiveness is verified—corrective actions prevent recurrence

- Process capability is quantified and improving (Cp, Cpk trending upward)

- Annual Product Reviews drive process improvements

- Knowledge management systems capture learnings from deviations, investigations, and inspections

- Quality culture is embedded—staff at all levels understand their role in maintaining control

- The organization actively seeks to falsify its own assumptions (the core principle of this blog)

Assessment Methods:

- Trending of process capability indices over time

- Review of Annual Product Reviews and management review meetings

- Audit of CAPA effectiveness (do similar deviations recur?)

- Statistical analysis of deviation rates and types

- Assessment of organizational culture (e.g., FDA’s QMM assessment)

- Evaluation of how the facility responds to “near-misses” and “weak signals”[blog]

Alignment with PreCheck: This is not explicitly evaluated in PreCheck as currently designed. PreCheck Phase 1 and Phase 2 focus on facility design and process execution, but do not assess long-term performance or organizational maturity.

However, the inclusion of Quality Management Maturity (QMM) practices in the Type V DMF is an attempt to evaluate this dimension. A facility with mature QMM practices is, in theory, more likely to remain “In Control” over time.

This also corresponds to routine re-inspections conducted every 1-3 years. The purpose of these inspections is not to re-validate the facility (which is already licensed), but to verify that the facility has maintained its validated state and has not accumulated unresolved compliance drift.

Inspection Outcome: If a facility is “In Control,” it means the organization has demonstrated sustained capability to manufacture products reliably. This is the goal of all GMP systems, but it is the hardest state to verify because it requires longitudinal data and cultural assessment, not just a snapshot inspection.

Mapping the Framework to Regulatory Timelines

The three-stage framework provides a logic for when and how to conduct regulatory inspections.

| Stage | Timing | Evaluation Method | FDA Equivalent | EMA Equivalent | Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Place | Before operations begin | Design review, document audit, installation verification | PreCheck Phase 1 (Facility Readiness) | Initial GMP inspection for license | Facility design flaws, inadequate documentation, unqualified equipment |

| In Use | During early operations | Process performance, batch record review, observation of operations | PreCheck Phase 2 / PAI/PLI | Pre-approval inspection (if needed) | Process failures, operator errors, inadequate training, poor execution |

| In Control | Ongoing (post-approval) | Trend analysis, statistical monitoring, culture assessment | Routine surveillance inspections, QMM assessment | Routine re-inspections (1-3 years) | Process drift, CAPA ineffectiveness, organizational complacency, systemic failures |

The current PAI/PLI model collapses “In Place,” “In Use,” and “In Control” into a single inspection event conducted at the worst possible time (near PDUFA). This creates the illusion that a facility’s compliance status can be determined in 5-10 days.

PreCheck separates “In Place” (Phase 1) from “In Use” (Phase 2), which is a significant improvement. But it still does not address the hardest question: how do we know a facility will remain “In Control” over time?

The answer is: you don’t. Not from a one-time inspection. You need continuous verification.

This is the insight embedded in the FDA’s 2011 process validation guidance: validation is not an event, it is a lifecycle. The validated state must be maintained through Stage 3 Continued Process Verification.

The same logic applies to facilities. A facility is not “validated” by passing a single PAI. It is validated by demonstrating control over time.

PreCheck needs to be part of a wider model at the FDA:

- Allow facilities that complete Phase 1 to earn presumption of compliance for future product applications (reducing PAI frequency)

- Implement more robust routine surveillance inspections on a 1-3 year cycle to verify “In Control” status. The data shows how much the FDA is missing this target.