The continued trend in FDA warning letters citing Quality Unit (QU) deficiencies highlights a concerning reality across pharmaceutical manufacturing operations worldwide. Three warning letters recently issued to pharmaceutical companies in China, India, and Malaysia reveal fundamental weaknesses in Quality Unit oversight that extend beyond isolated procedural failures to indicate systemic quality management deficiencies. These regulatory actions demonstrate the FDA’s continued emphasis on the Quality Unit as the cornerstone of pharmaceutical quality systems, with expectations that these units function as independent guardians of product quality with sufficient authority, resources, and expertise. This analysis examines the specific deficiencies identified across recent warning letters, identifies patterns of Quality Unit organizational failures, explores regulatory expectations, and provides strategic guidance for building robust quality oversight capabilities that meet evolving compliance standards.

Recent FDA Warning Letters Highlighting Critical Quality Unit Deficiencies

Multiple Geographic Regions Under Scrutiny

The FDA has continues to provide an intense focus on Quality Unit oversight through a series of warning letters targeting pharmaceutical operations across Asia. As highlighted in a May 19, 2025 GMP Compliance article, three notable warning letters targeted specific Quality Unit failures across multiple regions. The Chinese manufacturer failed to establish an adequate Quality Unit with proper authority to oversee manufacturing operations, particularly in implementing change control procedures and conducting required periodic product reviews. Similarly, the Indian manufacturer’s Quality Unit failed to implement controls ensuring data integrity, resulting in unacceptable documentation practices including torn batch records, damaged testing chromatograms, and improperly completed forms. The Malaysian facility, producing OTC products, showed failures in establishing adequate training programs and performing appropriate product reviews, further demonstrating systemic quality oversight weaknesses. These geographically diverse cases indicate that Quality Unit deficiencies represent a global challenge rather than isolated regional issues.

Historical Context of Regulatory Concerns

FDA’s focus on Quality Unit responsibilities isn’t new. A warning letter to a Thai pharmaceutical company earlier in 2024 cited Quality Unit deficiencies including lack of control over manufacturing operations, inadequate documentation of laboratory preparation, and insufficient review of raw analytical data. These issues allowed concerning practices such as production staff altering master batch records and using erasable markers on laminated sheets for production records. Another notable case involved Henan Kangdi Medical Devices, where in January 2020 the FDA stated explicitly that “significant findings in this letter indicate that your quality unit is not fully exercising its authority and/or responsibilities”. The consistent regulatory focus across multiple years suggests pharmaceutical manufacturers continue to struggle with properly empowering and positioning Quality Units within their organizational structures.

Geographic Analysis of Quality Unit Failures: Emerging vs. Mature Regulatory Markets

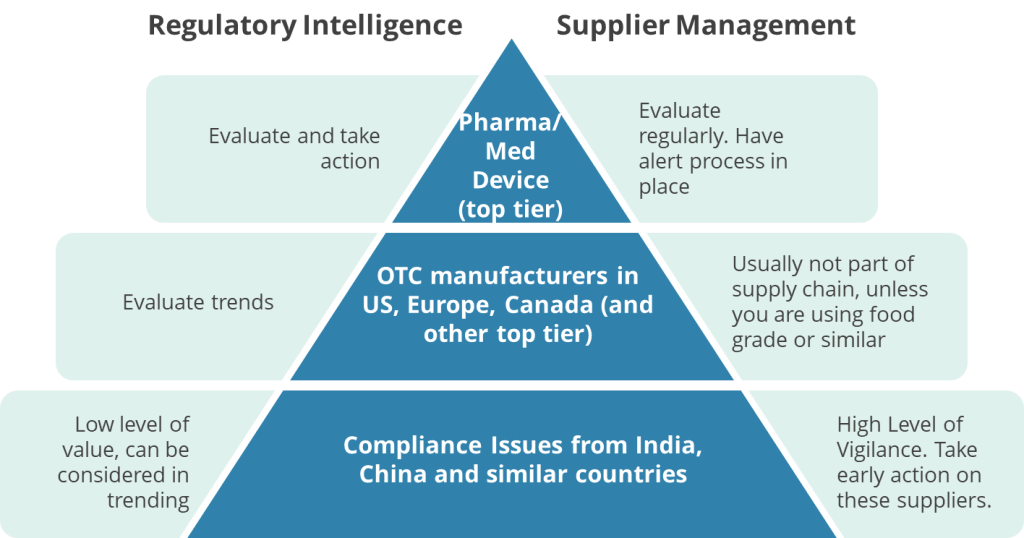

These FDA warning letters highlighting Quality Unit (QU) deficiencies reveal significant disparities between pharmaceutical manufacturing practices in emerging markets (e.g., China, India, Malaysia, Thailand) and mature regulatory jurisdictions (e.g., the U.S., EU, Japan). These geographic differences reflect systemic challenges tied to regulatory infrastructure, economic priorities, and technological adoption.

In emerging markets, structural weaknesses in regulatory oversight and quality culture dominate QU failures. For example, Chinese manufacturers like Linghai ZhanWang Biotechnology (2025) and Henan Kangdi (2019) faced FDA action because their Quality Units lacked the authority to enforce CGMP standards, with production teams frequently overriding quality decisions. Similarly, Indian facilities cited in 2025 warnings struggled with basic data integrity controls, including torn paper records and unreviewed raw data—issues exacerbated by domestic regulatory bodies like India’s CDSCO, which inspects fewer than 2% of facilities annually. These regions often prioritize production quotas over compliance, leading to under-resourced Quality Units and inadequate training programs, as seen in a 2025 warning letter to a Malaysian OTC manufacturer whose QU staff lacked GMP training. Supply chain fragmentation further complicates oversight, particularly in contract manufacturing hubs like Thailand, where a 2024 warning letter noted no QU review of outsourced laboratory testing.

By contrast, mature markets face more nuanced QU challenges tied to technological complexity and evolving regulatory expectations. In the U.S. and EU, recent warnings highlight gaps in Quality Units’ understanding of advanced manufacturing technologies, such as continuous manufacturing processes or AI-driven analytics. A 2024 EU warning letter to a German API manufacturer, for instance, cited cybersecurity vulnerabilities in electronic batch records—a stark contrast to emerging markets’ struggles with paper-based systems. While data integrity remains a global concern, mature markets grapple with sophisticated gaps like inadequate audit trails in cloud-based laboratory systems, whereas emerging economies face foundational issues like erased entries or unreviewed chromatograms. Regulatory scrutiny also differs: FDA inspection data from 2023 shows QU-related citations in just 6.2% of U.S. facilities versus 23.1% in Asian operations, reflecting stronger baseline compliance in mature jurisdictions.

Case comparisons illustrate these divergences. At an Indian facility warned in 2025, production staff routinely overruled QU decisions to meet output targets, while a 2024 U.S. warning letter described a Quality Unit delaying batch releases due to inadequate validation of a new AI-powered inventory system. Training gaps also differ qualitatively: emerging-market QUs often lack basic GMP knowledge, whereas mature-market teams may struggle with advanced tools like machine learning algorithms.

These geographic trends have strategic implications. Emerging markets require foundational investments in QU independence, such as direct reporting lines to executive leadership, and adoption of centralized digital systems to mitigate paper-record risks. Partnerships with mature-market firms could accelerate quality culture development. Meanwhile, mature jurisdictions must modernize QU training programs to address rapidly changing technologies and strengthen oversight of decentralized production models.

Data Integrity as a Critical Quality Unit Responsibility

Data integrity issues feature prominently in recent enforcement actions, reflecting the Quality Unit’s crucial role as guardian of trustworthy information. The FDA frequently requires manufacturers with data integrity deficiencies to engage third-party consultants to conduct comprehensive investigations into record inaccuracies across all laboratories, manufacturing operations, and relevant systems. These remediation efforts must identify numerous potential issues including omissions, alterations, deletions, record destruction, non-contemporaneous record completion, and other deficiencies that undermine data reliability. Thorough risk assessments must evaluate potential impacts on product quality, with companies required to implement both interim protective measures and comprehensive long-term corrective actions. These requirements underscore the fundamental importance of the Quality Unit in ensuring that product decisions are based on accurate, complete, and trustworthy data.

Patterns of Quality Unit Organizational Failures

Insufficient Authority and Resources

A recurring theme across warning letters is Quality Units lacking adequate authority or resources to fulfill their responsibilities effectively. The FDA’s warning letter to Linghai ZhanWang Biotechnology Co. in February 2025 cited violations that demonstrated the company’s Quality Unit couldn’t effectively ensure compliance with CGMP regulations. Similarly, Lex Inc. faced regulatory action when its “quality system was inadequate” because the Quality Unit “did not provide adequate oversight for the manufacture of over-the-counter (OTC) drug products”.

These cases reflect a fundamental organizational failure to empower Quality Units with sufficient authority and resources to perform their essential functions. Without proper positioning within the organizational hierarchy, Quality Units cannot effectively challenge manufacturing decisions that might compromise product quality or regulatory compliance, creating systemic vulnerabilities.

Documentation and Data Management Deficiencies

Quality Units frequently demonstrate inadequate oversight of documentation and data management processes, allowing significant compliance risks to emerge. According to FDA warning letters, these issues include torn batch records, incompletely documented laboratory preparation, inadequate retention of weight printouts, and insufficient review of raw analytical data. One particularly concerning practice involved “production records on laminated sheets using erasable markers that could be easily altered or lost,” representing a fundamental breakdown of documentation control. These examples demonstrate how Quality Unit failures in documentation oversight directly enable data integrity issues that can undermine the reliability of manufacturing records, ultimately calling product quality into question. Effective Quality Units must establish robust systems for ensuring complete, accurate, and contemporaneous documentation throughout the manufacturing process.

Inadequate Change Control and Risk Assessment

Change control deficiencies represent another significant pattern in Quality Unit failures. Warning letters frequently cite the Quality Unit’s failure to ensure appropriate change control procedures, highlighting inadequate risk assessments as a particular area of concern. FDA inspectors have found that inadequate change control practices present significant compliance risks, with change control appearing among the top ten FDA 483 violations. These deficiencies often involve failure to evaluate the potential impact of changes on product quality, incomplete documentation of changes, and improper execution of change implementation. Effective Quality Units must establish robust change control processes that include thorough risk assessments, appropriate approvals, and verification that changes have not adversely affected product quality.

Insufficient Batch Release and Production Record Review

Quality Units regularly fail to conduct adequate reviews of production records and properly execute batch release procedures. A frequent citation in warning letters involves the Quality Unit’s failure to “review production records to assure that no errors have occurred or, if errors have occurred, that they have been fully investigated”. In several cases, the Quality Unit reviewed only analytical results entered into enterprise systems without examining the underlying raw analytical data, creating significant blind spots in quality oversight. This pattern demonstrates a superficial approach to batch review and release decisions that fails to fulfill the Quality Unit’s fundamental responsibility to ensure each batch meets all established specifications before distribution. Comprehensive batch record review is essential for detecting anomalies that might indicate quality or compliance issues requiring investigation.

Regulatory Expectations for Effective Quality Units

Core Quality Unit Responsibilities

The FDA has clearly defined the essential responsibilities of the Quality Unit through regulations, guidance documents, and enforcement actions. According to 21 CFR 211.22, the Quality Unit must “have the responsibility and authority to approve or reject all components, drug product containers, closures, in-process materials, packaging material, labeling, and drug products”. Additionally, the unit must “review production records to assure that no errors have occurred or, if errors have occurred, that they have been fully investigated”. FDA guidance elaborates that the Quality Unit’s duties include “ensuring that controls are implemented and completed satisfactorily during manufacturing operations” and “ensuring that developed procedures and specifications are appropriate and followed”. These expectations establish the Quality Unit as both guardian and arbiter of quality throughout the manufacturing process, with authority to make critical decisions regarding product acceptability.

Independence and Organizational Structure

Regulatory authorities expect Quality Units to maintain appropriate independence from production units to prevent conflicts of interest. FDA guidance specifically states that “under a quality system, it is normally expected that the product and process development units, the manufacturing units, and the QU will remain independent”. This separation ensures that quality decisions remain objective and focused on product quality rather than production metrics or efficiency considerations. While the FDA acknowledges that “in very limited circumstances, a single individual can perform both production and quality functions,” such arrangements require additional safeguards including “another qualified individual, not involved in the production operation, conduct[ing] an additional, periodic review of QU activities”. This guidance underscores the critical importance of maintaining appropriate separation between quality and production responsibilities.

Quality System Integration

Regulatory authorities increasingly view the Quality Unit as the central coordinator of a comprehensive quality system. The FDA’s guidance document “Quality Systems Approach to Pharmaceutical CGMP Regulations” positions the Quality Unit as responsible for creating, monitoring, and implementing the entire quality system. This expanded view recognizes that while the Quality Unit doesn’t assume responsibilities belonging to other organizational units, it plays a crucial role in ensuring that all departments understand and fulfill their quality-related responsibilities. The Quality Unit must therefore establish appropriate communication channels and collaborative mechanisms with other functional areas while maintaining the independence necessary to make objective quality decisions. This integrated approach recognizes that quality management extends beyond a single department to encompass all activities affecting product quality.

Strategic Approaches to Strengthening Quality Unit Effectiveness

Comprehensive Quality System Assessment

Organizations facing Quality Unit deficiencies should begin remediation with a thorough assessment of their entire pharmaceutical quality system. Warning letters frequently require companies to conduct “a comprehensive assessment and remediation plan to ensure your QU is given the authority and resources to effectively function”. This assessment should examine whether procedures are “robust and appropriate,” how the Quality Unit provides oversight “throughout operations to evaluate adherence to appropriate practices,” the effectiveness of batch review processes, and the Quality Unit’s investigational capabilities. A thorough gap analysis should compare current practices against regulatory requirements and industry best practices to identify specific areas requiring improvement. This comprehensive assessment provides the foundation for developing targeted remediation strategies that address the root causes of Quality Unit deficiencies.

Establishing Clear Roles and Adequate Resources

Effective remediation requires clearly defining Quality Unit roles and ensuring adequate resources to fulfill regulatory responsibilities. FDA warning letters frequently cite the absence of “written procedures for QU roles and responsibilities” as a significant deficiency. Organizations must develop detailed written procedures that clearly articulate the Quality Unit’s authority and responsibilities, including approval or rejection authority for components and drug products, review of production records, and oversight of quality-impacting procedures and specifications. Additionally, companies must assess whether Quality Units have sufficient staffing with appropriate qualifications and training to effectively execute these responsibilities. This assessment should consider both the number of personnel and their technical capabilities relative to the complexity of manufacturing operations and product portfolio.

Implementing Robust Data Integrity Controls

Data integrity represents a critical area requiring focused attention from Quality Units. Companies must implement comprehensive data governance systems that ensure records are attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, and accurate (ALCOA principles). Quality Units should establish oversight mechanisms for all quality-critical data, including laboratory results, manufacturing records, and investigation documentation. These systems must include appropriate controls for paper records and electronic data, with verification processes to ensure consistency between different data sources. Quality Units should also implement risk-based audit programs that regularly evaluate data integrity practices across all manufacturing and laboratory operations. These controls provide the foundation for trustworthy data that supports sound quality decisions and regulatory compliance.

Developing Management Support and Quality Culture

Sustainable improvements in Quality Unit effectiveness require strong management support and a positive quality culture throughout the organization. FDA warning letters specifically call for “demonstration of top management support for quality assurance and reliable operations, including timely provision of resources to address emerging manufacturing and quality issues”. Executive leadership must visibly champion quality as an organizational priority and empower the Quality Unit with appropriate authority to fulfill its responsibilities effectively. Organizations should implement programs that promote quality awareness at all levels, with particular emphasis on the shared responsibility for quality across all departments. Performance metrics and incentive structures should align with quality objectives to reinforce desired behaviors and decision-making patterns. This culture change requires consistent messaging, appropriate resource allocation, and leadership accountability for quality outcomes.

Conclusion

FDA warning letters reveal persistent Quality Unit deficiencies across global pharmaceutical operations, with significant implications for product quality and regulatory compliance. The patterns identified—including insufficient authority and resources, documentation and data management weaknesses, inadequate change control, and ineffective batch review processes—highlight the need for fundamental improvements in how Quality Units are structured, resourced, and empowered within pharmaceutical organizations. Regulatory expectations clearly position the Quality Unit as the cornerstone of effective pharmaceutical quality systems, with responsibility for ensuring that all operations meet established quality standards through appropriate oversight, review, and decision-making processes.

Addressing these challenges requires a strategic approach that begins with comprehensive assessment of current practices, establishment of clear roles and responsibilities, implementation of robust data governance systems, and development of a supportive quality culture. Organizations that successfully strengthen their Quality Units can not only avoid regulatory action but also realize significant operational benefits through more consistent product quality, reduced manufacturing deviations, and more efficient operations. As regulatory scrutiny of Quality Unit effectiveness continues to intensify, pharmaceutical manufacturers must prioritize these improvements to ensure sustainable compliance and protect patient safety in an increasingly complex manufacturing environment.

Key Warning Letters Discussed

- Linghai ZhanWang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China) — February 25, 2025

- (For the original FDA letter, search the FDA Warning Letters database for “Linghai ZhanWang Biotechnology Co” and the date “02/25/2025”)

- Henan Kangdi Medical Devices Co. Ltd. (China) — December 3, 2019

- (For the original FDA letter, search the FDA Warning Letters database for “Henan Kangdi Medical Devices” and the date “12/03/2019”)

- Drug Manufacturing Facility in Thailand — February 27, 2024

- (For the original FDA letter, search the FDA Warning Letters database for “Thailand” and the date “02/27/2024”)

- BioAsia Worldwide (Malaysia) — February 2025

- (For the original FDA letter, search the FDA Warning Letters database for “BioAsia Worldwide” and the date “02/2025”)

For the most authoritative and up-to-date versions, always use the FDA Warning Letters database and search by company name and date.