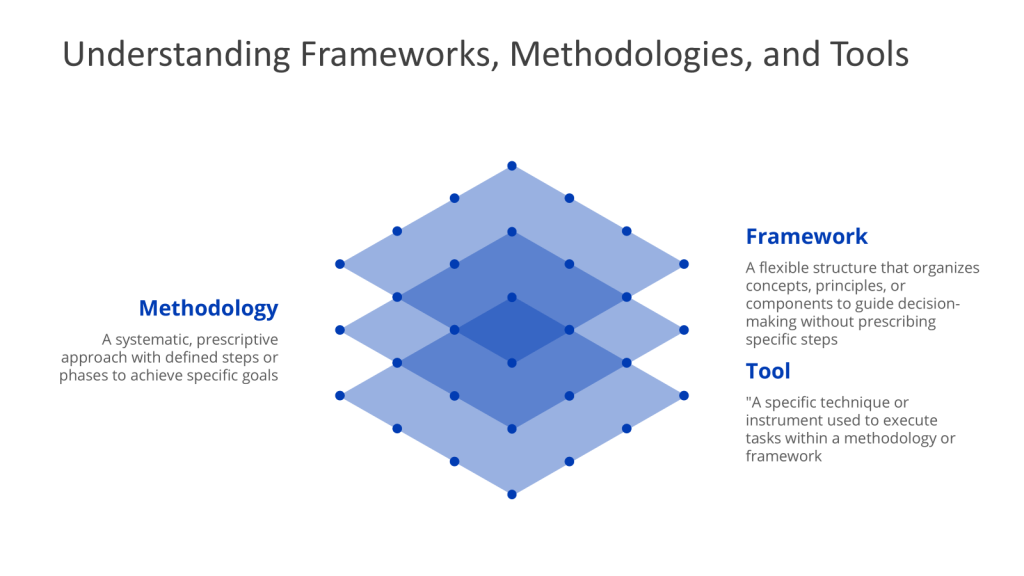

We often encounter three fundamental concepts in quality management: methodologies, frameworks, and tools. Despite their critical importance in shaping how we approach challenges, these terms are frequently unclear. It is pretty easy to confuse these concepts, using them interchangeably or misapplying them in practice.

This confusion is not merely a matter of semantics. Misunderstandings or misapplications of methodologies, frameworks, and tools can lead to ineffective problem-solving, misaligned strategies, and suboptimal outcomes. When we fail to distinguish between a methodology’s structured approach, a framework’s flexible guidance, and a tool’s specific function, we risk applying the wrong solution to our challenges or missing out on creative opportunities from their proper use.

In this blog post, I will provide clear definitions, illustrate their interrelationships, and demonstrate their real-world application. By doing so, we will clarify these often-confused terms and show how their proper understanding and application can significantly enhance our approach to quality management and other critical business processes.

Framework: The Conceptual Scaffolding

A framework is a flexible structure that organizes concepts, principles, and practices to guide decision-making. Unlike methodologies, frameworks are not rigidly sequential; they provide a mental model or lens through which problems can be analyzed. Frameworks emphasize what needs to be addressed rather than how to address it.

For example:

- Systems Thinking Frameworks conceptualize problems as interconnected components (e.g., inputs, processes, outputs).

- QbD Frameworks outline elements like Quality Target Product Profiles (QTPP) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) to embed quality into product design.

Frameworks enable adaptability, allowing practitioners to tailor approaches to specific contexts while maintaining alignment with overarching goals.

Methodology: The Structured Pathway

A methodology is a systematic, step-by-step approach to solving problems or achieving objectives. It provides a structured sequence of actions, often grounded in theoretical principles, and defines how tasks should be executed. Methodologies are prescriptive, offering clear guidelines to ensure consistency and repeatability.

For example:

- Six Sigma follows the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) methodology to reduce process variation.

- 8D (Eight Disciplines) is a problem-solving methodology with steps like containment, root cause analysis, and preventive action.

Methodologies act as “recipes” that standardize processes across teams, making them ideal for regulated industries (e.g., pharmaceuticals) where auditability and compliance are critical.

Tool: The Tactical Instrument

A tool is a specific technique, model, or instrument used to execute tasks within a methodology or framework. Tools are action-oriented and often designed for a singular purpose, such as data collection, analysis, or visualization.

For example:

- Root Cause Analysis Tools: Fishbone diagrams, Why-Why, and Pareto charts.

- Process Validation Tools: Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts, Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA).

Tools are the “nuts and bolts” that operationalize methodologies and frameworks, converting theory into actionable insights.

How They Interrelate: Building a Cohesive Strategy

Methodologies, frameworks, and tools are interdependent. A framework provides the conceptual structure for understanding a problem, the methodology defines the execution plan, and tools enable practical implementation.

Example in Systems Thinking:

- Framework: Systems theory identifies inputs, processes, outputs, and feedback loops.

- Methodology: A 5-phase approach (problem structuring, dynamic modeling, scenario planning) guides analysis.

- Tools: Causal loop diagrams map relationships; simulation software models system behavior.

In QbD:

- Framework: The ICH Q8 guideline outlines quality objectives.

- Methodology: Define QTPP → Identify Critical Quality Attributes → Design experiments.

- Tools: Design of Experiments (DoE) optimizes process parameters.

In Commissioning, Qualification, and Validation (CQV)

- Framework: Regulatory guidelines (e.g., FDA’s Process Validation Lifecycle) define stages (Commissioning → Qualification → Validation).

- Methodology:

- Commissioning: Factory Acceptance Testing (FAT) ensures equipment meets design specs.

- Qualification: Installation/Operational/Performance Qualification (IQ/OQ/PQ) methodologies verify functionality.

- Validation: Ongoing process verification ensures consistent quality.

- Tools: Checklists (IQ), stress testing (OQ), and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring.

Without frameworks, methodologies lack context; without tools, methodologies remain theoretical.

Quality Management in the Model

Quality management is not inherently a framework, but rather an overarching concept that can be implemented through various frameworks, methodologies, and tools.

Quality management encompasses a broad range of activities aimed at ensuring products, services, and processes meet consistent quality standards. It can be implemented using different approaches:

- Quality Management Frameworks: These provide structured systems for managing quality, such as:

- ISO 9001: A set of guidelines for quality management systems

- Total Quality Management (TQM): An integrative system focusing on customer satisfaction and continuous improvement

- Pharmaceutical Quality System: As defined by ICH Q10 and other regulations and guidance

- Quality Management Methodologies: These offer systematic approaches to quality management, including:

- Six Sigma: A data-driven methodology for eliminating defects

- Lean: A methodology focused on minimizing waste while maximizing customer value

- Quality Management Tools: There are too many tools to count (okay I have a few books on my shelf that try) but tools are usually built to meet the core elements that make up quality management practices:

- Quality Planning

- Quality Assurance

- Quality Control

- Quality Improvement

In essence, quality management is a comprehensive approach that can be structured and implemented using various frameworks, but it is not itself a framework.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA): Framework or Methodology?

Root cause analysis (RCA) functions as both a framework and a methodology, depending on its application and implementation.

Root Cause Analysis as a Framework

RCA serves as a framework when it provides a conceptual structure for organizing causal analysis without prescribing rigid steps. It offers:

- Guiding principles: Focus on systemic causes over symptoms, emphasis on evidence-based analysis.

- Flexible structure: Adaptable to diverse industries (e.g., healthcare, manufacturing) and problem types.

- Tool integration: Accommodates methods like 5 Whys, Fishbone diagrams, and Fault Tree Analysis.

Root Cause Analysis as a Methodology

RCA becomes a methodology when applied as a systematic process with defined steps:

- Problem definition: Quantify symptoms and impacts.

- Data collection: Gather evidence through interviews, logs, or process maps.

- Causal analysis: Use tools like 5 Whys or Fishbone diagrams to trace root causes.

- Solution implementation: Design corrective actions targeting systemic gaps.

| Approach | Classification | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Six Sigma | Methodology (DMAIC/DMADV) | Structured phases (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) for defect reduction. |

| 8D | Methodology | Eight disciplines for containment, root cause analysis, and preventive action. |

| RCA Tools | Tools (e.g., 5 Whys, Fishbone) | Tactical instruments used within methodologies. |

- RCA is a framework when providing a scaffold for causal analysis (e.g., categorizing causes into human/process/systemic factors).

- RCA becomes a methodology when systematized into phases (e.g., 5 Whys) or integrated into broader methodologies like Six Sigma.

- Six Sigma and 8D are methodologies, not frameworks, due to their prescriptive, phase-based structures.

This duality allows RCA to adapt to contexts ranging from incident reviews to engineering failure analysis, making it a versatile approach for systemic problem-solving.

Synergy for Systemic Excellence

Methodologies provide the roadmap, frameworks offer the map, and tools equip the journey. In systems thinking and QbD, their integration ensures holistic problem-solving—whether optimizing manufacturing validation (CQV) or eliminating defects (Six Sigma). By anchoring these elements in process thinking, organizations transform isolated actions into coherent, quality-driven systems. Clarity on these distinctions isn’t academic; it’s the foundation of sustainable excellence.

| Aspect | Framework | Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Flexible, conceptual | Rigid, step-by-step |

| Application | Guides analysis | Prescribes execution |

Great work as always. Would you be able to do a follow up on the importance of starting from framework to really define what youre doing before going to the tool which is the how. I have often seen newer professionals jump right to the tool because they have seen it used successfully elsewhere. But if they had started from the framework, they would realize that the tool is not the best. This also comes up from time to time with more experience professionals but that is usually related to the cycle of complacency. Again great post and thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you!

I love this idea. Any preferred topic/framework you’d like a deep dive analysis around as an example?

LikeLike

I have a continuous process validation example. We employ control charts to monitor our process almost universally. However, we found that for some quality parameters nearly all of the data was below the Limit of Quantification. Thus, our rule 1 violations (outside of 3 SD from the mean) were really just identifying an atypical LOQ (potentially atypical analytic performance) and not atypical process performance.

The CPV framework aims to ensure that the process continues to remain in a validated state, but the use of the control chart as a tool to execute the monitoring was inappropriate in this situation. By jumping right to the tool of control charts we generated quite a few investigations that were effectively false positive signals about our process. After identifying the situation, we moved to a monitoring system of responding to any above LOQ results which better fit our CPV framework. Of note, the process capability for this parameter was very high so the variability in LOQ didnt pose a risk to the process as the LOQ <<< alert/action limit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I took a stab at answering: https://investigationsquality.com/2025/03/30/continuous-process-verification-cpv-methodology-and-tool-selection-a-framework-guided-by-fda-process-validation/

LikeLike