As pharmaceutical and biotech organizations rush to harness artificial intelligence to eliminate “inefficient” entry-level positions, we are at risk of creating a crisis that threatens the very foundation of quality expertise. The Harvard Business Review’s recent analysis of AI’s impact on entry-level jobs reads like a prophecy of organizational doom—one that quality leaders should heed before it’s too late.

Research from Stanford indicates that there has been a 13% decline in entry-level job opportunities for workers aged 22 to 25 since the widespread adoption of generative AI. The study shows that 50-60% of typical junior tasks—such as report drafting, research synthesis, data cleaning, and scheduling—can now be performed by AI. For high-quality organizations already facing expertise gaps, this trend signals a potential self-destructive path rather than increased efficiency.

Equally concerning, automation is leading to the phasing out of some traditional entry-level professional tasks. When I started in the field, newcomers would gain experience through tasks like batch record reviews and good documentation practices for protocols. However, with the introduction of electronic batch records and electronic validation management, these tasks have largely disappeared. AI is expected to accelerate this trend even further.

Everyone should go and read “The Perils of Using AI to Replace Entry-Level Jobs” by Amy C. Edmondson and Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic and then come back and read this post.

The Apprenticeship Dividend: What We Lose When We Skip the Journey

Every expert in pharmaceutical quality began somewhere. They learned to read batch records, investigated their first deviations, struggled through their first CAPA investigations, and gradually developed the pattern recognition that distinguishes competent from exceptional quality professionals. This journey, what the Edmondson and Chamorro-Premuzic call the “apprenticeship dividend”, cannot be replicated by AI or compressed into senior-level training programs.

Consider commissioning, qualification, and validation (CQV) work in biotech manufacturing. Junior engineers traditionally started by documenting Installation Qualification protocols, learning to recognize when equipment specifications align with user requirements. They progressed to Operational Qualification, developing understanding of how systems behave under various conditions. Only after this foundation could they effectively design Performance Qualification strategies that demonstrate process capability.

When organizations eliminate these entry-level CQV roles in favor of AI-generated documentation and senior engineers managing multiple systems simultaneously, they create what appears to be efficiency. In reality, they’ve severed the pipeline that transforms technical contributors into systems thinkers capable of managing complex manufacturing operations.

The Expertise Pipeline: Building Quality Gardeners

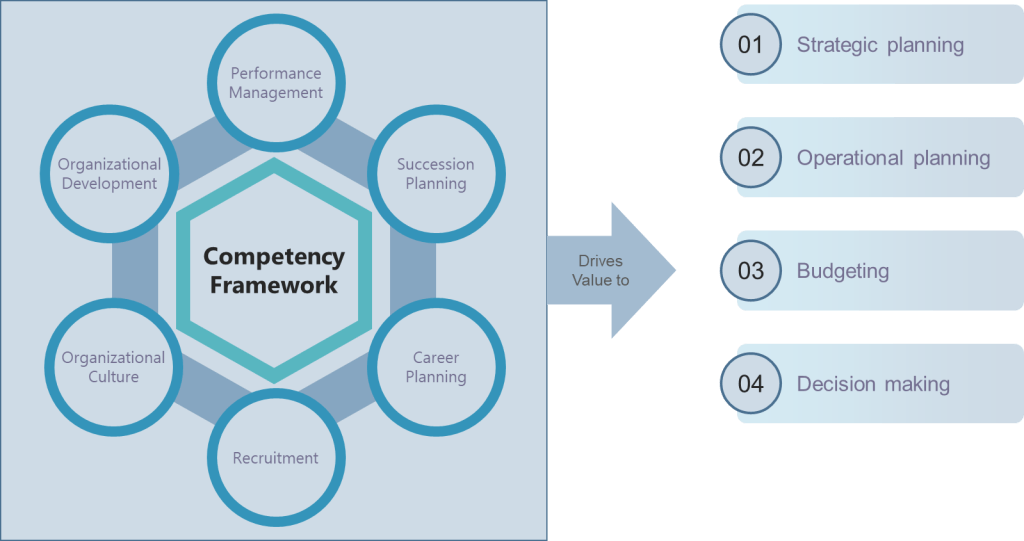

As I’ve written previously about building competency frameworks for quality professionals, true expertise requires integration of technical knowledge, methodological skills, social capabilities, and self-management abilities. This integration occurs through sustained practice, mentorship, and gradual assumption of responsibility—precisely what entry-level positions provide.

The traditional path from Quality specialist to Quality Manager to Quality Director illustrates this progression:

Foundation Level: Learning to execute quality methods methods, understand requirements, and recognize when results fall outside acceptance criteria. Basic deviation investigation and CAPA support.

Intermediate Level: Taking ownership of requirement gathering, leading routine investigations, participating in supplier audits, and beginning to see connections between different quality systems.

Advanced Level: Designing audit activities, facilitating cross-functional investigations, mentoring junior staff, and contributing to strategic quality initiatives.

Leadership Level: Building quality cultures, designing organizational capabilities, and creating systems that enable others to excel.

Each level builds upon the previous, creating what we might call “quality gardeners”—professionals who nurture quality systems as living ecosystems rather than enforcing compliance through rigid oversight. Skip the foundation levels, and you cannot develop the sophisticated understanding required for advanced practice.

The False Economy of AI Substitution

Organizations defending entry-level job elimination often point to cost savings and “efficiency gains.” This thinking reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how expertise develops and quality systems function. Consider risk management in biotech manufacturing—a domain where pattern recognition and contextual judgment are essential.

A senior risk management professional reviewing a contamination event can quickly identify potential failure modes, assess likelihood and severity, and design effective mitigation strategies. This capability developed through years of investigating routine deviations, participating in CAPA teams, and learning to distinguish significant risks from minor variations.

When AI handles initial risk assessments and senior professionals review only the outputs, we create a dangerous gap. The senior professional lacks the deep familiarity with routine variations that enables recognition of truly significant deviations. Meanwhile, no one is developing the foundational expertise needed to replace retiring experts.

The result is what is called expertise hollowing, organizations that appear capable on the surface but lack the deep competency required to handle complex challenges or adapt to changing conditions.

Building Expertise in a Quality Organization

Creating robust expertise development requires intentional design that recognizes both the value of human development and the capabilities of AI tools. Rather than eliminating entry-level positions, quality organizations should redesign them to maximize learning value while leveraging AI appropriately.

Structured Apprenticeship Programs

Quality organizations should implement formal apprenticeship programs that combine academic learning with progressive practical responsibility. These programs should span 2-3 years and include:

Year 1: Foundation Building

- Basic GMP principles and quality systems overview

- Hands-on experience with routine quality operations

- Mentorship from experienced quality professionals

- Participation in investigations under supervision

Year 2: Skill Development

- Specialized training in areas like CQV, risk management, or supplier quality

- Leading routine activities with oversight

- Cross-functional project participation

- Beginning to train newer apprentices

Year 3: Integration and Leadership

- Independent project leadership

- Mentoring responsibilities

- Contributing to strategic quality initiatives

- Preparation for advanced roles

As I evaluate the organization I am building, this is a critical part of the vision.

Mentorship as Core Competency

Every senior quality professional should be expected to mentor junior colleagues as a core job responsibility, not an additional burden. This requires:

- Formal Mentorship Training: Teaching experienced professionals how to transfer tacit knowledge, provide effective feedback, and create learning opportunities.

- Protected Time: Ensuring mentors have dedicated time for development activities, not just “additional duties as assigned.”

- Measurement Systems: Tracking mentorship effectiveness through apprentice progression, retention rates, and long-term career development.

- Recognition Programs: Rewarding excellent mentorship as a valued contribution to organizational capability.

Progressive Responsibility Models

Entry-level roles should be designed with clear progression pathways that gradually increase responsibility and complexity:

CQV Progression Example:

- CQV Technician: Executing test protocols, documenting results, supporting commissioning activities

- CQV Specialist: Writing protocols, leading qualification activities, interfacing with vendors

- CQV Engineer: Designing qualification strategies, managing complex projects, training others

- CQV Manager: Building organizational CQV capabilities, strategic planning, external representation

Risk Management Progression:

- Risk Analyst: Data collection, basic risk identification, supporting formal assessments

- Risk Specialist: Facilitating risk assessments, developing mitigation strategies, training stakeholders

- Risk Manager: Designing risk management systems, building organizational capabilities, strategic oversight

AI as Learning Accelerator, Not Replacement

Rather than replacing entry-level workers, AI should be positioned as a learning accelerator that enables junior professionals to handle more complex work earlier in their careers:

- Enhanced Analysis Capabilities: AI can help junior professionals identify patterns in large datasets, enabling them to focus on interpretation and decision-making rather than data compilation.

- Simulation and Modeling: AI-powered simulations can provide safe environments for junior professionals to practice complex scenarios without real-world consequences.

- Knowledge Management: AI can help junior professionals access relevant historical examples, best practices, and regulatory guidance more efficiently.

- Quality Control: AI can help ensure that junior professionals’ work meets standards while they’re developing expertise, providing a safety net during the learning process.

The Cost of Expertise Shortcuts

Organizations that eliminate entry-level positions in pursuit of short-term efficiency gains will face predictable long-term consequences:

- Expertise Gaps: As senior professionals retire or move to other organizations, there will be no one prepared to replace them.

- Reduced Innovation: Innovation often comes from fresh perspectives questioning established practices—precisely what entry-level employees provide.

- Cultural Degradation: Quality cultures are maintained through socialization and shared learning experiences that occur naturally in diverse, multi-level teams.

- Risk Blindness: Without the deep familiarity that comes from hands-on experience, organizations become vulnerable to risks they cannot recognize or understand.

- Competitive Disadvantage: Organizations with strong expertise development programs will attract and retain top talent while building superior capabilities.

Choosing Investment Over Extraction

The decision to eliminate entry-level positions represents a choice between short-term cost extraction and long-term capability investment. For quality organizations, this choice is particularly stark because our work depends fundamentally on human judgment, pattern recognition, and the ability to adapt to novel situations.

AI should augment human capability, not replace the human development process. The organizations that thrive in the next decade will be those that recognize expertise development as a core competency and invest accordingly. They will build “quality gardeners” who can nurture adaptive, resilient quality systems rather than simply enforce compliance.

The expertise crisis is not inevitable—it’s a choice. Quality leaders must choose wisely, before the cost of that choice becomes irreversible.

2 thoughts on “The Expertise Crisis: Why AI’s War on Entry-Level Jobs Threatens Quality Excellence”