In my previous post, “The Effectiveness Paradox: Why ‘Nothing Bad Happened’ Doesn’t Prove Your Quality System Works”, I challenged a core assumption underpinning how the pharmaceutical industry evaluates its quality systems. We have long mistaken the absence of negative events—no deviations, no recalls, no adverse findings—for evidence of effectiveness. As I argued, this is not proof of success, but rather a logical fallacy: conflating absence of evidence with evidence of absence, and building unfalsifiable systems that teach us little about what truly works.

But recognizing the limits of “nothing bad happened” as a quality metric is only the starting point. The real challenge is figuring out what comes next: How do we move from defensive, unfalsifiable quality posturing toward a framework where our systems can be genuinely and rigorously tested? How do we design quality management approaches that not only anticipate success but are robust enough to survive—and teach us from—failure?

The answer begins with transforming the way we frame and test our assumptions about quality performance. Enter structured hypothesis formation: a disciplined, scientific approach that takes us from passive observation to active, falsifiable prediction. This methodology doesn’t just close the door on the effectiveness paradox—it opens a new frontier for quality decision-making grounded in scientific rigor, predictive learning, and continuous improvement.

The Science of Structured Hypothesis Formation

Structured hypothesis formation differs fundamentally from traditional quality planning by emphasizing falsifiability and predictive capability over compliance demonstration. Where traditional approaches ask “How can we prove our system works?” structured hypothesis formation asks “What specific predictions can our quality system make, and how can these predictions be tested?”

The core principles of structured hypothesis formation in quality systems include:

Explicit Prediction Generation: Quality hypotheses must make specific, measurable predictions about system behavior under defined conditions. Rather than generic statements like “our cleaning process prevents cross-contamination,” effective hypotheses specify conditions: “our cleaning procedure will reduce protein contamination below 10 ppm within 95% confidence when contact time exceeds 15 minutes at temperatures above 65°C.”

Testable Mechanisms: Hypotheses should articulate the underlying mechanisms that drive quality outcomes. This moves beyond correlation toward causation, enabling genuine process understanding rather than statistical association.

Failure Mode Specification: Effective quality hypotheses explicitly predict how and when systems will fail, creating opportunities for proactive detection and mitigation rather than reactive response.

Uncertainty Quantification: Rather than treating uncertainty as weakness, structured hypothesis formation treats uncertainty quantification as essential for making informed quality decisions under realistic conditions.

Framework for Implementation: The TESTED Approach

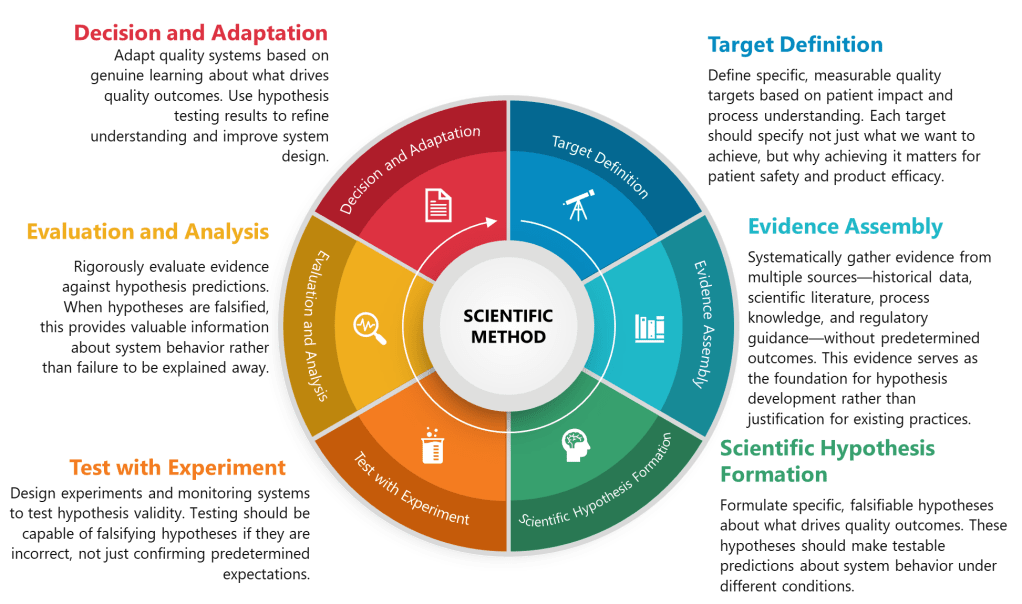

The practical implementation of structured hypothesis formation in pharmaceutical quality systems can be systematized through what I call the TESTED framework—a six-phase approach that transforms traditional quality activities into hypothesis-driven scientific inquiry:

T – Target Definition

Traditional Approach: Identify potential quality risks through brainstorming or checklist methods.

TESTED Approach: Define specific, measurable quality targets based on patient impact and process understanding. Each target should specify not just what we want to achieve, but why achieving it matters for patient safety and product efficacy.

E – Evidence Assembly

Traditional Approach: Collect available data to support predetermined conclusions.

TESTED Approach: Systematically gather evidence from multiple sources—historical data, scientific literature, process knowledge, and regulatory guidance—without predetermined outcomes. This evidence serves as the foundation for hypothesis development rather than justification for existing practices.

S – Scientific Hypothesis Formation

Traditional Approach: Develop risk assessments based on expert judgment and generic failure modes.

TESTED Approach: Formulate specific, falsifiable hypotheses about what drives quality outcomes. These hypotheses should make testable predictions about system behavior under different conditions.

T – Testing Design

Traditional Approach: Design validation studies to demonstrate compliance with predetermined acceptance criteria.

TESTED Approach: Design experiments and monitoring systems to test hypothesis validity. Testing should be capable of falsifying hypotheses if they are incorrect, not just confirming predetermined expectations.

E – Evaluation and Analysis

Traditional Approach: Analyze results to demonstrate system adequacy.

TESTED Approach: Rigorously evaluate evidence against hypothesis predictions. When hypotheses are falsified, this provides valuable information about system behavior rather than failure to be explained away.

D – Decision and Adaptation

Traditional Approach: Implement controls based on risk assessment outcomes.

TESTED Approach: Adapt quality systems based on genuine learning about what drives quality outcomes. Use hypothesis testing results to refine understanding and improve system design.

Application Examples

Cleaning Validation Transformation

Traditional Approach: Demonstrate that cleaning procedures consistently achieve residue levels below acceptance criteria.

TESTED Implementation:

- Target: Prevent cross-contamination between products while optimizing cleaning efficiency

- Evidence: Historical contamination data, scientific literature on cleaning mechanisms, process capability data

- Hypothesis: Contact time with cleaning solution above 12 minutes combined with mechanical action intensity >150 RPM will achieve >99.9% protein removal regardless of product sequence, with failure probability <1% when both parameters are maintained simultaneously

- Testing: Designed experiments varying contact time and mechanical action across different product sequences

- Evaluation: Results confirmed the importance of the interaction but revealed that product sequence affects required contact time by up to 40%

- Decision: Revised cleaning procedure to account for product-specific requirements while maintaining hypothesis-driven monitoring

Process Control Strategy Development

Traditional Approach: Establish critical process parameters and control limits based on process validation studies.

TESTED Implementation:

- Target: Ensure consistent product quality while enabling process optimization

- Evidence: Process development data, literature on similar processes, regulatory precedents

- Hypothesis: Product quality is primarily controlled by the interaction between temperature (±2°C) and pH (±0.1 units) during the reaction phase, with environmental factors contributing <5% to overall variability when these parameters are controlled

- Testing: Systematic evaluation of parameter interactions using designed experiments

- Evaluation: Temperature-pH interaction confirmed, but humidity found to have >10% impact under specific conditions

- Decision: Enhanced control strategy incorporating environmental monitoring with hypothesis-based action limits

3 thoughts on “Building Decision-Making with Structured Hypothesis Formation”