Environmental monitoring (EM) is not a hygiene check. It is a story we tell ourselves about whether our contamination control strategy actually works.

On paper, EM is straightforward: pick locations, define limits, collect samples, trend the data, investigate excursions. In practice, it sits at the messy intersection of microbiology, human behavior, facility design, and what I’ve elsewhere called unfalsifiable control strategies. When it works, EM quietly falsifies our fears by showing the facility behaving as predicted. When it fails, it often fails by never really testing the prediction in the first place.

This post is about that failure mode. More specifically, it is about two parts of the EM ecosystem that are chronically underpowered: trending and investigation. If you’ve read my earlier piece on Risk Assessment for Environmental Monitoring, think of this as the sequel where the risk model has to face its least forgiving critic: reality.

What Environmental Monitoring Is Really For

We often say EM is about verifying “state of control” in cleanrooms. It is a phrase that sounds reassuring and says almost nothing. State of control relative to what?

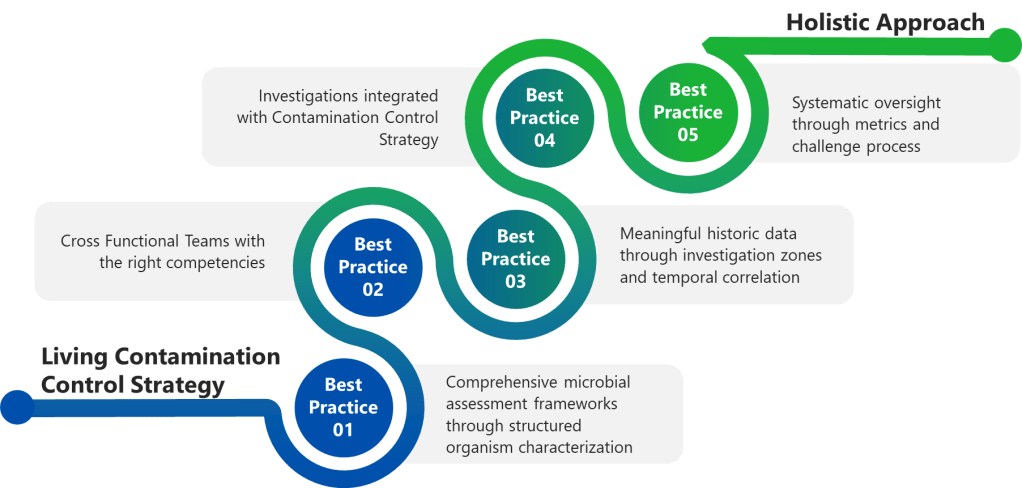

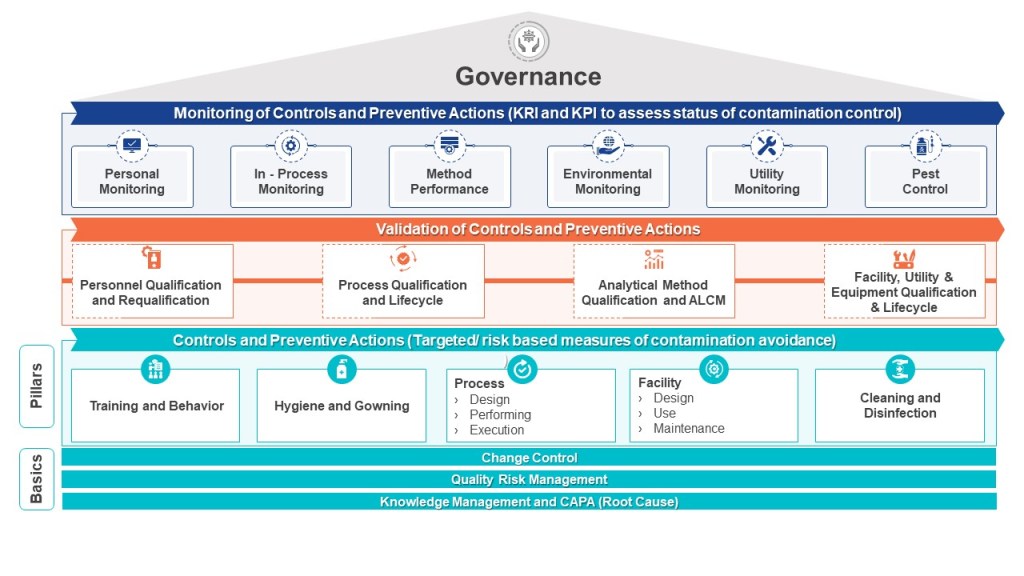

In Risk Assessment for Environmental Monitoring, I argued that an EM program should be anchored in a living risk assessment that behaves more like a heat map than a checklist. The assessment looks at:

- Amenability of equipment and surfaces to cleaning and disinfection

- Personnel presence and flow

- Material flow and hand‑offs

- Proximity to open product or direct-contact surfaces

- Complexity and frequency of interventions

The result is not just a pretty risk matrix to staple behind Annex 1. It is a falsifiable prediction:

Given this process, this design, and these behaviors, contamination is most likely to appear here, here, and here.

Environmental monitoring is the ongoing experiment we run against that prediction. Every plate, every settle dish, every active air sample is data in a long-running test: does the world behave the way our contamination control strategy (CCS) says it should?

That framing matters. It changes the central trending question from “Are we under our alert and action limits?” to “Are the patterns we see consistent with the story our CCS tells?”

In Contamination Control, Risk Management and Change Control, I wrote that contamination control is a risk management problem that must be dynamically updated as we learn. EM is where that learning is supposed to happen. A CCS that cannot be contradicted by EM data is not a strategy; it is a belief system.

Aspirational Data vs Representative Data

Before we talk about trending, we have to talk about the data we are trending. Environmental monitoring quietly encourages a particular pathology: the production of aspirational data.

Aspirational data capture how we wish the facility behaved. Representative data capture how it actually behaves. The differences are subtle and often invisible in a quarterly slide deck.

Common ways organizations drift toward aspiration:

- Pre-cleaned sampling. The team “freshens” the line before the EM tech arrives, creating a pristine snapshot of a room that never exists during peak operations.

- Special sampling behavior. Operators slow their movements, avoid borderline practices, and “try harder” when plates are out. EM never sees the way work happens at 02:00 on day seven of a long campaign.

- Convenience-based sites. Surfaces that are easy to access become the de facto sampling plan. Awkward, congested, or genuinely risky locations become afterthoughts.

- Frozen plans. Once a sampling plan is approved, changing it is culturally hard. Risk shifts, processes evolve, but the plan clings to the path of least resistance.

The result is a dataset that looks pleasant in management reviews but has low epistemic value. It cannot falsify the CCS because it rarely goes near the conditions where the CCS is most likely to fail.

In Control Strategies, I described control strategies as knowledge systems that depend on feedback loops. EM is one of those loops. When EM is restricted to safe sampling, we quietly turn down the volume on our feedback. We get charts that signal control regardless of what is happening in the real system.

When an inspector asks, “How do you know this program is representative of normal operations?”, the reflex is to present design-intent documents: risk assessments, HVAC diagrams, EM SOPs. We rarely acknowledge the human side:

- “We always clean right before EM.”

- “Operators adjust their behavior during sampling.”

But these are exactly the kinds of issues that decide whether EM is a diagnostic or a performance. Representative programs will, at times, generate ugly data. That is what makes trending worth doing.

Trending as Hypothesis Testing, Not Chart Decoration

Trending has become a ritual. EM SOPs promise regular trend analysis. Quarterly reports bristle with plots and heat maps. Warning letter responses swear that “trends are monitored.”

Yet, in practice, most trending boils down to two actions:

- Plot excursion counts or percentages by area/quarter.

- Confirm that they are below predefined thresholds (excursion rate limits, contamination recovery rate limits, etc.).

This can catch gross failures. It does little for the subtler changes that matter most.

The Wrong Question: “Are We Under the Number?”

When trending is reduced to “staying under 1% excursions” or “within CRR limits,” we are asking the wrong question. Limits are not magic; they are guesses, often conservative and sometimes inherited, about what “normal” should look like.

If your excursion rate moves from 0.05% to 0.4% to 0.8% across four quarters and your only commentary is “still under 1%,” you are treating an arbitrary number as a metaphysical boundary. The system is speaking; you are ignoring it because the cell in the dashboard is still green.

The same goes for contamination recovery rates. USP <1116> introduced CRR specifically to get us away from binary hit/no‑hit thinking. But CRR can easily become just another “good/bad” threshold if we do not embed it in a broader hypothesis test.

The Right Question: “What Pattern Would Falsify Our Story?”

In my 2025 retrospective, I described investigations as opportunities to falsify the control strategy. Trending is the front end of that logic. Before you can falsify a story, you must decide what would count as falsification.

Most EM programs are full of unspoken hypotheses:

- “If excursion rate ever exceeds X, we have a problem.”

- “If mold appears in Grade C, the building envelope is compromised.”

- “If we see TNTC in this room, an operator did something dramatically wrong.”

These thoughts exist as hallway comments and private thresholds in managers’ heads. They rarely make it into procedures.

A mature trending program would make them explicit. For example:

- Predefined trend triggers:

- Four consecutive quarters of increasing excursion rate, regardless of absolute level.

- A statistically significant increase in CRR versus the prior two-year baseline.

- Recurrence of the same organism species in the same location over multiple months.

- Emergence of organisms outside the current disinfectant challenge panel.

- Explicit CCS linkages:

- “This pattern would contradict our assumption that weekly sporicide is sufficient in Buffer Prep.”

- “This cluster would contradict our assumption that the gowning procedure is robust under peak traffic.”

In the Rechon warning letter post, I emphasized temporal correlation: contamination patterns aligned with specific campaigns, maintenance events, or staffing changes are not curiosities; they are tests of our explanatory model. Trend analysis that never confronts the CCS with these tests remains decorative.

Three Levels of Trend Analysis

Practically, it helps to distinguish three nested levels of trend analysis:

- Descriptive – What happened?

- Excursion counts and percentages by room, grade, quarter.

- CRR by parameter and area versus internal limits and historical baselines.

- Organism distributions over time.

- Relational – What does it correlate with?

- Overlay EM excursions with campaign schedules, change controls, shutdowns, HVAC events, and staffing patterns.

- Ask, “When X happens, does Y tend to happen as well?”

- Explanatory – What does this say about our CCS?

- Map observed trends back to specific CCS elements: cleaning regime, gowning, HVAC, material/personnel flow.

- Ask, “If this pattern persists, which CCS or risk assessment statements would we need to rewrite?”

Most organizations live at level 1, dabble in level 2, and rarely touch level 3. But level 3 is where trending actually becomes hypothesis testing.

In The Quality Continuum in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing, I wrote about QC’s role in providing continuity across detection, response, and learning. EM trending is one of the places QC can either uphold that continuum or quietly break it by staying at the descriptive level.

Seasonal Molds and Convenient Amnesia

Seasonality is a good example of where EM trending and investigation often part ways with reality.

Many facilities can tell you, in a hand-wavy way, that “we always see more molds in the fall” or “pollen season is rough on our Grade D.” Fewer can show you a disciplined comparison of Q4 versus Q4 across multiple years, with room-by-room and species-level analysis.

The usual pattern looks like this:

- A cluster of mold excursions appears in Q4.

- Each individual event is investigated as a standalone deviation: root cause “seasonal loading,” “door left open,” “operator movement,” etc.

- The quarterly report notes an “increase in mold recoveries consistent with seasonal variation.”

- No one actually compares the magnitude and distribution of this Q4 spike to prior years in a way that could falsify the “just seasonal” story.

The phrase “consistent with” is doing a lot of work there. Consistent with does not mean explained by. It means “we can imagine a world where this pattern is seasonal.”

A more disciplined approach would:

- Collect 3–5 years of Q4 data and compare mold counts and species distributions to other quarters.

- Look at spatial patterns: are these molds appearing in the same areas repeatedly, or migrating?

- Correlate with facility and CCS changes: new disinfectants, altered cleaning frequencies, HVAC modifications, construction, landscaping changes.

If the story is “seasonal loading,” that story should make predictions:

- The spike should repeat with roughly similar magnitude and species profile year-on-year, absent major changes in controls.

- Rooms with greater exchange with the external environment should be more affected than those with tight controls.

If those predictions do not hold, the hypothesis fails. Perhaps what we actually have is a cleaning regime that is adequate at baseline but fragile under seasonal stress; or a building envelope that slowly degraded; or a CCS that never truly considered spores as a separate risk dimension.

Trending without this kind of explicit, falsifiable seasonal analysis can lull us into a comforting narrative about inevitable variation, instead of pushing us to ask whether our controls are robust enough.

Investigation as the Continuation of Trending

If trending is hypothesis testing at the population level, investigation is the continuation of that testing at the event level.

In several posts, I have written about investigation craft:

- Using cognitive interviewing instead of leading questions.

- Avoiding the “Golden Day” fallacy, where we focus only on what was different on the day it went wrong and ignore the many days it went right.

- Distinguishing between negative reasoning (“no evidence of”) and causal reasoning (“this factor contributed to…”).

EM gives us a special sort of investigation problem. We are often dealing with:

- Low signal-to-noise ratio.

- Long latency between event and detection.

- Data that are inherently spatial and temporal (room, site, campaign, season).

When an EM excursion occurs, the temptation is to compress the narrative down to the single day, the single shift, the single operator. We write: “On this day, operator X failed to do Y, leading to Z.”

That can be true. It is rarely the whole truth.

The Golden Day vs the Typical Day

The Golden Day fallacy appears when we contrast the excursion day to an imaginary “typical day” and then attribute all differences to the excursion. The problem is that most of the time, we do not actually understand what a typical day looks like in any rigorous sense.

Trending should inform that understanding. For example:

- If a room has a history of low-level hits clustered around certain interventions, then seeing a spike during such an intervention may be a case of the same mechanism operating more strongly, not a unique one-off.

- If a species has appeared sporadically over months across different surfaces, the excursion might be the moment the underlying reservoir finally crossed a threshold, not the moment the contamination was created.

Good EM investigations make heavy use of trend data as context. They ask:

- “What does the last year of data in this room look like?”

- “Have we seen this organism before, and where?”

- “Which parts of the CCS would predict that this should not happen here?”

The investigation then moves from “What happened on Tuesday?” to “What does Tuesday tell us about a pattern we may have been ignoring?”

Negative Evidence and Silent Failures

Another trap in EM investigations is the overuse of negative evidence:

- “No HVAC deviations were noted.”

- “Cleaning logs were complete.”

- “No maintenance activities were recorded.”

Each of these is a statement about documentation, not reality. They are not useless—records matter—but they are not the same as positive evidence of proper behavior.

When we string together a series of “no deviations noted” statements and conclude that “no systemic issues were identified,” we have quietly moved from absence of evidence to evidence of absence.

Trend-informed EM investigations counter this by looking for silent failures:

- If we see a slow increase in low-level counts in a room with “perfect” cleaning records, what does that say about the sensitivity of our cleaning oversight?

- If we consistently recover organisms that our disinfectant efficacy studies never challenged, what does that say about our DE study design?

In other words, investigations should use EM data to question the sensitivity and specificity of our own controls, not just to confirm that paperwork exists.

A Composite Case: When EM Told Two Stories

Consider a composite, anonymized scenario that will feel familiar.

Over the course of a year, a facility sees:

- A quarterly excursion rate that increases from 0.1% to 0.7%, always under the 1.0% internal limit.

- Recurrent viable air excursions and occasional TNTC readings in two Grade C cell culture rooms during peak campaigns.

- A cluster of mold recoveries in Q4 in both Grade C and D areas, including species not previously seen at the site.

- A contamination recovery rate that remains within internal CRR limits for all grades.

The quarterly EM report dutifully notes:

- “Excursion rate remains below 1%; EM program continues to demonstrate control.”

- “Increased excursions seen in Grade C areas consistent with high activity.”

- “Mold recoveries consistent with seasonal variation.”

Investigations for the individual deviations attribute causes to:

- Operator aseptic technique.

- Increased production activity.

- Seasonal mold loading.

No trend deviation is opened. No update is made to the CCS.

From a strict, spec-driven point of view, this is plausible. From a hypothesis-testing point of view, it is deeply unsatisfying.

A more ambitious approach would treat the year’s data as a falsification challenge to the CCS:

- The CCS claimed cleaning frequencies and disinfectant rotation were sufficient for Grade C under expected facility loading. Yet under peak load, the system appears fragile.

- The CCS claimed gowning procedures and personnel flow were robust for cell culture operations. Recurrent TNTC and high viable air counts suggest a different story.

- The CCS and DE study implicitly assumed the disinfectant panel and contact times were adequate against relevant molds. The appearance of new species and seasonal clustering should trigger a revisit of those assumptions.

In this view, the “trend deviation” is not an administrative nicety. It is the vehicle for making the CCS falsification explicit and forcing the organization to decide:

- Do we update the control strategy and invest in new controls?

- Or do we defend the current strategy with stronger evidence?

Either answer is more honest than quietly declaring everything “within limits.”

Making EM Falsifiable by Design

If EM is going to function as a falsifiable story rather than a compliance ritual, a few design principles help.

1. Design for Representation, Not Respectability

Sampling plans should start from the premise that data will sometimes be uncomfortable. That means:

- Sampling when rooms are at their busiest, not when they are at their tidiest.

- Including sites that are awkward, noisy, or politically sensitive because they are truly high risk.

- Formalizing in procedures that pre‑cleaning specifically for EM is not permitted (and verifying this in practice).

If EM results never make anyone uncomfortable, they are probably not representative.

2. Treat Risk Assessments as Versioned Hypotheses

The EM risk assessment and CCS should be treated as versioned, hypothesis-bearing documents:

- Each version should explicitly state key assumptions: e.g., “Weekly sporicide is sufficient for Grade C floors under expected traffic.”

- Trend analysis should regularly review whether observed patterns still align with those assumptions.

- When they do not, the CCS and risk assessment should be revised, not simply the justification text.

This links EM data to change control in a way that Contamination Control, Risk Management and Change Control sketched conceptually but rarely gets fully implemented.

3. Use Annual Organism Review as a Falsification Step

Annual organism reviews for disinfectant challenge panels are often treated as administrative ticks: yes, we still have a Gram-positive, a Gram-negative, a yeast, a mold, and maybe a facility isolate or two.

A more useful review would ask:

- Which organisms actually dominated our EM recoveries this year?

- Which organisms recurred in high-risk rooms?

- Which organisms appeared for the first time, and where?

- Which of these are covered by our current disinfectant efficacy panel, and which are not?

When there is a mismatch, that is a hypothesis failure: our DE panel is not representative of the real flora. The response might be to:

- Add one or two high-frequency isolates to the next DE study.

- Re‑evaluate contact times or concentrations.

- Re-examine how disinfectant is applied in challenging locations.

This turns the organism review into an explicit test of how well our lab studies generalize to the field.

4. Integrate Trend Triggers into Investigation Governance

Trend triggers—like consecutive quarters of increase, or recurrent species in a location—should be codified and tied directly to deviation types. For example:

- “Any four-quarter monotonic increase in excursion rate in a grade triggers a site-level EM trend deviation.”

- “Any repeated recovery of the same mold in the same room over three months triggers a mold trend deviation.”

These trend deviations should then be treated with the same seriousness as a major one-off excursion, because they represent repeated falsification of a CCS assumption, not a single-point failure.

Culture: Pretty Charts vs Uncomfortable Truths

Behind all of this sits culture. Environmental monitoring lives in a tension between two expectations:

- Regulators expect EM to be representative of normal operations.

- Leadership often expects EM results to be respectable—low, stable, reassuring.

Those expectations are not always compatible.

A representative EM program will sometimes show uncomfortable patterns:

- A room that is chronically fragile under certain campaigns.

- A mold species that stubbornly reappears despite cleaning.

- A slow drift upward in viable counts in a high-risk area.

If every excursion turns into a hunt for the “operator at fault,” people learn quickly that ignorance is safer than insight. Sampling windows get narrowed, “special cleaning” becomes routine, and the data gradually become aspirational.

Building a culture where EM can falsify our own stories requires a few commitments:

- An excursion is the start of a learning conversation, not the end of a blame assignment.

- Trend deviations are opportunities to reconsider strategies, not black marks.

- Quality and operations jointly own the CCS and EM program; neither can use the other as a shield.

In Lessons from the Rechon Life Science Warning Letter, I argued that contamination events are often the visible tip of a long, shared history of decisions that made the system brittle. EM is one of the few tools that can reveal that history in real time—if we let it.

Questions to Ask of Your Own EM Program

If you want to stress-test your own EM trending and investigation system, a few questions can help. Treat this as a discussion tool, not a checklist.

About representation

- When are most of your EM samples taken: during peak activity or during “quiet times”?

- If you shadowed an EM tech for a week, what unwritten rules would you see about when and where they really sample?

About risk and CCS

- Can you point to specific CCS statements that your EM data are actively testing?

- When was the last time an EM trend led to a formal change to the CCS, rather than just a CAPA or training?

About trending

- Do your trend reports do more than plot counts versus limits?

- Have you defined patterns (e.g., consecutive increases, changing organism profiles) that automatically trigger deeper review?

About investigation

- How often do EM investigations bring in trend data from previous months as part of the causal reasoning?

- How often does the conclusion “no systemic issue identified” rest primarily on “no deviations found in records”?

About organisms and disinfectants

- Does your current disinfectant efficacy panel match the organisms you actually recover?

- Have you added or removed isolates based on organism review in the last three years?

If the honest answers make you uncomfortable, that is a good sign. It means there is room to turn EM from a hygiene ritual into a genuine falsification engine for your control strategy.

Environmental monitoring is, at its best, a continuous experiment we run on our own systems. Every sample is an invitation for the facility to contradict the story we tell about it. Trending and investigation are how we listen to those contradictions and decide whether to learn from them or explain them away.

We can continue to treat EM as a series of charts we wave at auditors. Or we can treat it as evidence in an ongoing argument between our control strategies and the stubbornness of reality.

The second option is harder. It is also the only one that moves us forward.

f