In my recent exploration of the Jobs-to-Be-Done tool I examined how customer-centric thinking could revolutionize our understanding of complex quality processes. Today, I want to extend that analysis to one of the most persistent challenges in pharmaceutical data integrity: determining when electronic signatures are truly required to meet regulatory standards and data integrity expectations.

Most organizations approach electronic signature decisions through what I call “compliance theater”—mechanically applying rules without understanding the fundamental jobs these signatures need to accomplish. They focus on regulatory checkbox completion rather than building genuine data integrity capability. This approach creates elaborate signature workflows that satisfy auditors but fail to serve the actual needs of users, processes, or the data integrity principles they’re meant to protect.

The cost of getting this wrong extends far beyond regulatory findings. When organizations implement electronic signatures incorrectly, they create false confidence in their data integrity controls while potentially undermining the very protections these signatures are meant to provide. Conversely, when they avoid electronic signatures where they would genuinely improve data integrity, they perpetuate manual processes that introduce unnecessary risks and inefficiencies.

The Electronic Signature Jobs Users Actually Hire

When quality professionals, process owners and system owners consider electronic signature requirements, what job are they really trying to accomplish? The answer reveals a profound disconnect between regulatory intent and operational reality.

The Core Functional Job

“When I need to ensure data integrity, establish accountability, and meet regulatory requirements for record authentication, I want a signature method that reliably links identity to action and preserves that linkage throughout the record lifecycle, so I can demonstrate compliance and maintain trust in my data.”

This job statement immediately exposes the inadequacy of most electronic signature decisions. Organizations often focus on technical implementation rather than the fundamental purpose: creating trustworthy, attributable records that support decision-making and regulatory confidence.

The Consumption Jobs: The Hidden Complexity

Electronic signature decisions involve numerous consumption jobs that organizations frequently underestimate:

- Evaluation and Selection: “I need to assess when electronic signatures provide genuine value versus when they create unnecessary complexity.”

- Implementation and Training: “I need to build electronic signature capability without overwhelming users or compromising data quality.”

- Maintenance and Evolution: “I need to keep my signature approach current as regulations evolve and technology advances.”

- Integration and Governance: “I need to ensure electronic signatures integrate seamlessly with my broader data integrity strategy.”

These consumption jobs represent the difference between electronic signature systems that users genuinely want to hire and those they grudgingly endure.

The Emotional and Social Dimensions

Electronic signature decisions involve profound emotional and social jobs that traditional compliance approaches ignore:

- Confidence: Users want to feel genuinely confident that their signature approach provides appropriate protection, not just regulatory coverage.

- Professional Credibility: Quality professionals want signature systems that enhance rather than complicate their ability to ensure data integrity.

- Organizational Trust: Executive teams want assurance that their signature approach genuinely protects data integrity rather than creating administrative overhead.

- User Acceptance: Operational staff want signature workflows that support rather than impede their work.

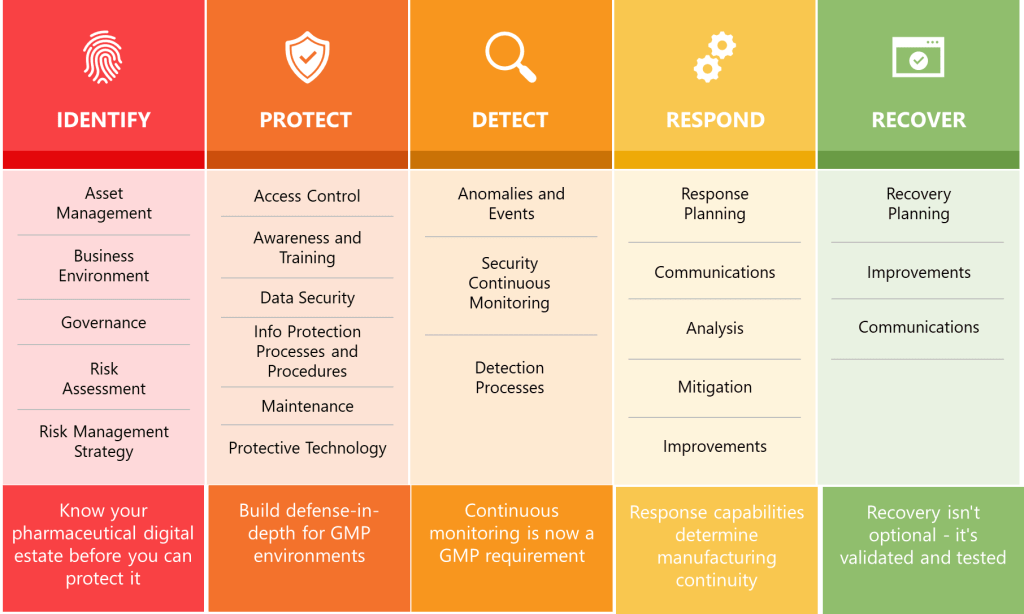

The Current Regulatory Landscape: Beyond the Checkbox

Understanding when electronic signatures are required demands a sophisticated appreciation of the regulatory landscape that extends far beyond simple rule application.

FDA 21 CFR Part 11: The Foundation

21 CFR Part 11 establishes that electronic signatures can be equivalent to handwritten signatures when specific conditions are met. However, the regulation’s scope is explicitly limited to situations where signatures are required by predicate rules—the underlying FDA regulations that mandate signatures for specific activities.

The critical insight that most organizations miss: Part 11 doesn’t create new signature requirements. It simply establishes standards for electronic signatures when signatures are already required by other regulations. This distinction is fundamental to proper implementation.

Key Part 11 requirements include:

- Unique identification for each individual

- Verification of signer identity before assignment

- Certification that electronic signatures are legally binding equivalents

- Secure signature/record linking to prevent falsification

- Comprehensive signature manifestations showing who signed what, when, and why

EU Annex 11: The European Perspective

EU Annex 11 takes a similar approach, requiring that electronic signatures “have the same impact as hand-written signatures”. However, Annex 11 places greater emphasis on risk-based decision making throughout the computerized system lifecycle.

Annex 11’s approach to electronic signatures emphasizes:

- Risk assessment-based validation

- Integration with overall data integrity strategy

- Lifecycle management considerations

- Supplier assessment and management

GAMP 5: The Risk-Based Framework

GAMP 5 provides the most sophisticated framework for electronic signature decisions, emphasizing risk-based approaches that consider patient safety, product quality, and data integrity throughout the system lifecycle.

GAMP 5’s key principles for electronic signature decisions include:

- Risk-based validation approaches

- Supplier assessment and leverage

- Lifecycle management

- Critical thinking application

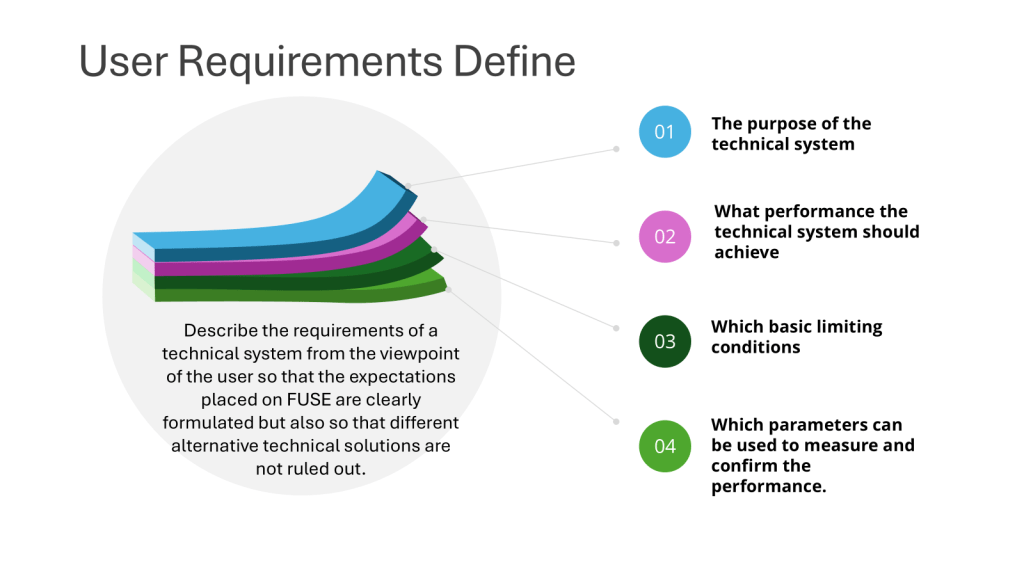

- User requirement specification based on intended use

The Predicate Rule Reality: Where Signatures Are Actually Required

The foundation of any electronic signature decision must be a clear understanding of where signatures are required by predicate rules. These requirements fall into several categories:

- Manufacturing Records: Batch records, equipment logbooks, cleaning records where signature accountability is mandated by GMP regulations.

- Laboratory Records: Analytical results, method validations, stability studies where analyst and reviewer signatures are required.

- Quality Records: Deviation investigations, CAPA records, change controls where signature accountability ensures proper review and approval.

- Regulatory Submissions: Clinical data, manufacturing information, safety reports where signatures establish accountability for submitted information.

The critical insight: electronic signatures are only subject to Part 11 requirements when handwritten signatures would be required in the same circumstances.

The Eight-Step Electronic Signature Decision Framework

Applying the Jobs-to-Be-Done universal job map to electronic signature decisions reveals where current approaches systematically fail and how organizations can build genuinely effective signature strategies.

Step 1: Define Context and Purpose

What users need: Clear understanding of the business process, data integrity requirements, regulatory obligations, and decisions the signature will support.

Current reality: Electronic signature decisions often begin with technology evaluation rather than purpose definition, leading to solutions that don’t serve actual needs.

Best practice approach: Begin every electronic signature decision by clearly articulating:

- What business process requires authentication

- What regulatory requirements mandate signatures

- What data integrity risks the signature will address

- What decisions the signed record will support

- Who will use the signature system and in what context

Step 2: Locate Regulatory Requirements

What users need: Comprehensive understanding of applicable predicate rules, data integrity expectations, and regulatory guidance specific to their process and jurisdiction.

Current reality: Organizations often apply generic interpretations of Part 11 or Annex 11 without understanding the specific predicate rule requirements that drive signature needs.

Best practice approach: Systematically identify:

- Specific predicate rules requiring signatures for your process

- Applicable data integrity guidance (MHRA, FDA, EMA)

- Relevant industry standards (GAMP 5, ICH guidelines)

- Jurisdictional requirements for your operations

- Industry-specific guidance for your sector

Step 3: Prepare Risk Assessment

What users need: Structured evaluation of risks associated with different signature approaches, considering patient safety, product quality, data integrity, and regulatory compliance.

Current reality: Risk assessments often focus on technical risks rather than the full spectrum of data integrity and business risks associated with signature decisions.

Best practice approach: Develop comprehensive risk assessment considering:

- Patient safety implications of signature failure

- Product quality risks from inadequate authentication

- Data integrity risks from signature system vulnerabilities

- Regulatory risks from non-compliant implementation

- Business risks from user acceptance and system reliability

- Technical risks from system integration and maintenance

Step 4: Confirm Decision Criteria

What users need: Clear criteria for evaluating signature options, with appropriate weighting for different risk factors and user needs.

Current reality: Decision criteria often emphasize technical features over fundamental fitness for purpose, leading to over-engineered or under-protective solutions.

Best practice approach: Establish explicit criteria addressing:

- Regulatory compliance requirements

- Data integrity protection level needed

- User experience and adoption requirements

- Technical integration and maintenance needs

- Cost-benefit considerations

- Long-term sustainability and evolution capability

Step 5: Execute Risk Analysis

What users need: Systematic comparison of signature options against established criteria, with clear rationale for recommendations.

Current reality: Risk analysis often becomes feature comparison rather than genuine assessment of how different approaches serve the jobs users need accomplished.

Best practice approach: Conduct structured analysis that:

- Evaluates each option against established criteria

- Considers interdependencies with other systems and processes

- Assesses implementation complexity and resource requirements

- Projects long-term implications and evolution needs

- Documents assumptions and limitations

- Provides clear recommendation with supporting rationale

Step 6: Monitor Implementation

What users need: Ongoing validation that the chosen signature approach continues to serve its intended purposes and meets evolving requirements.

Current reality: Organizations often treat electronic signature implementation as a one-time decision rather than an ongoing capability requiring continuous monitoring and adjustment.

Best practice approach: Establish monitoring systems that:

- Track signature system performance and reliability

- Monitor user adoption and satisfaction

- Assess continued regulatory compliance

- Evaluate data integrity protection effectiveness

- Identify emerging risks or opportunities

- Measure business value and return on investment

Step 7: Modify Based on Learning

What users need: Responsive adjustment of signature strategies based on monitoring feedback, regulatory changes, and evolving business needs.

Current reality: Electronic signature systems often become static implementations, updated only when forced by system upgrades or regulatory findings.

Best practice approach: Build adaptive capability that:

- Regularly reviews signature strategy effectiveness

- Updates approaches based on regulatory evolution

- Incorporates lessons learned from implementation experience

- Adapts to changing business needs and user requirements

- Leverages technological advances and industry best practices

- Maintains documentation of changes and rationale

Step 8: Conclude with Documentation

What users need: Comprehensive documentation that captures the rationale for signature decisions, supports regulatory inspections, and enables knowledge transfer.

Current reality: Documentation often focuses on technical specifications rather than the risk-based rationale that supports the decisions.

Best practice approach: Create documentation that:

- Captures the complete decision rationale and supporting analysis

- Documents risk assessments and mitigation strategies

- Provides clear procedures for ongoing management

- Supports regulatory inspection and audit activities

- Enables knowledge transfer and training

- Facilitates future reviews and updates

The Risk-Based Decision Tool: Moving Beyond Guesswork

The most critical element of any electronic signature strategy is a robust decision tool that enables consistent, risk-based choices. This tool must address the fundamental question: when do electronic signatures provide genuine value over alternative approaches?

The Electronic Signature Decision Matrix

The decision matrix evaluates six critical dimensions:

Regulatory Requirement Level:

- High: Predicate rules explicitly require signatures for this activity

- Medium: Regulations require documentation/accountability but don’t specify signature method

- Low: Good practice suggests signatures but no explicit regulatory requirement

Data Integrity Risk Level:

- High: Data directly impacts patient safety, product quality, or regulatory submissions

- Medium: Data supports critical quality decisions but has indirect impact

- Low: Data supports operational activities with limited quality impact

Process Criticality:

- High: Process failure could result in patient harm, product recall, or regulatory action

- Medium: Process failure could impact product quality or regulatory compliance

- Low: Process failure would have operational impact but limited quality implications

User Environment Factors:

- High: Users are technically sophisticated, work in controlled environments, have dedicated time for signature activities

- Medium: Users have moderate technical skills, work in mixed environments, have competing priorities

- Low: Users have limited technical skills, work in challenging environments, face significant time pressures

System Integration Requirements:

- High: Must integrate with validated systems, requires comprehensive audit trails, needs long-term data integrity

- Medium: Moderate integration needs, standard audit trail requirements, medium-term data retention

- Low: Limited integration needs, basic documentation requirements, short-term data use

Business Value Potential:

- High: Electronic signatures could significantly improve efficiency, reduce errors, or enhance compliance

- Medium: Moderate improvements in operational effectiveness or compliance capability

- Low: Limited operational or compliance benefits from electronic implementation

Decision Logic Framework

Electronic Signature Strongly Recommended (Score: 15-18 points):

All high-risk factors align with strong regulatory requirements and favorable implementation conditions. Electronic signatures provide clear value and are essential for compliance.

Electronic Signature Recommended (Score: 12-14 points):

Multiple risk factors support electronic signature implementation, with manageable implementation challenges. Benefits outweigh costs and complexity.

Electronic Signature Optional (Score: 9-11 points):

Mixed risk factors with both benefits and challenges present. Decision should be based on specific organizational priorities and capabilities.

Alternative Controls Preferred (Score: 6-8 points):

Low regulatory requirements combined with implementation challenges suggest alternative controls may be more appropriate.

Electronic Signature Not Recommended (Score: Below 6 points):

Risk factors and implementation challenges outweigh potential benefits. Focus on alternative controls and process improvements.

Implementation Guidance by Decision Category

For Strongly Recommended implementations:

- Invest in robust, validated electronic signature systems

- Implement comprehensive training and competency programs

- Establish rigorous monitoring and maintenance procedures

- Plan for long-term system evolution and regulatory changes

For Recommended implementations:

- Consider phased implementation approaches

- Focus on high-value use cases first

- Establish clear success metrics and monitoring

- Plan for user adoption and change management

For Optional implementations:

- Conduct detailed cost-benefit analysis

- Consider pilot implementations in specific areas

- Evaluate alternative approaches simultaneously

- Maintain flexibility for future evolution

For Alternative Controls approaches:

- Focus on strengthening existing manual controls

- Consider semi-automated approaches (e.g., witness signatures, timestamp logs)

- Plan for future electronic signature capability as conditions change

- Maintain documentation of decision rationale for future reference

Practical Implementation Strategies: Building Genuine Capability

Effective electronic signature implementation requires attention to three critical areas: system design, user capability, and governance frameworks.

System Design Considerations

Electronic signature systems must provide robust identity verification that meets both regulatory requirements and practical user needs. This includes:

Authentication and Authorization:

- Multi-factor authentication appropriate to risk level

- Role-based access controls that reflect actual job responsibilities

- Session management that balances security with usability

- Integration with existing identity management systems where possible

Signature Manifestation Requirements:

Regulatory requirements for signature manifestation are explicit and non-negotiable. Systems must capture and display:

- Printed name of the signer

- Date and time of signature execution

- Meaning or purpose of the signature (approval, review, authorship, etc.)

- Unique identification linking signature to signer

- Tamper-evident presentation in both electronic and printed formats

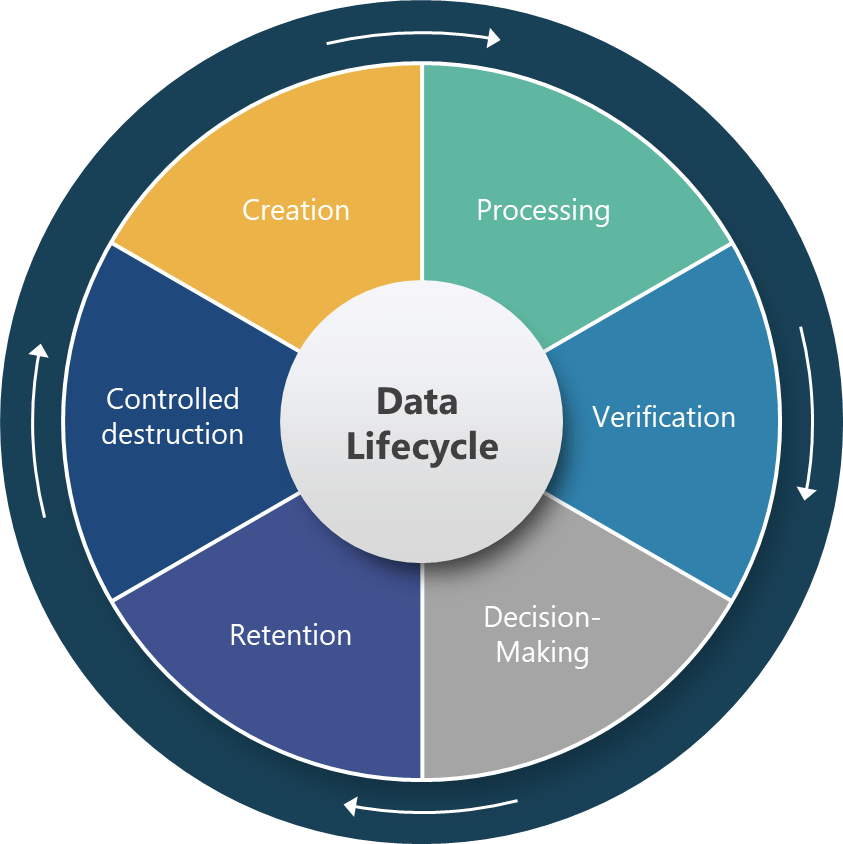

Audit Trail and Data Integrity:

Electronic signature systems must provide comprehensive audit trails that support both routine operations and regulatory inspections. Essential capabilities include:

- Immutable recording of all signature-related activities

- Comprehensive metadata capture (who, what, when, where, why)

- Integration with broader system audit trail capabilities

- Secure storage and long-term preservation of audit information

- Searchable and reportable audit trail data

System Integration and Interoperability:

Electronic signatures rarely exist in isolation. Effective implementation requires:

- Seamless integration with existing business applications

- Consistent user experience across different systems

- Data exchange standards that preserve signature integrity

- Backup and disaster recovery capabilities

- Migration planning for system upgrades and replacements

Training and Competency Development

User Training Programs:

Electronic signature success depends critically on user competency. Effective training programs address:

- Regulatory requirements and the importance of signature integrity

- Proper use of signature systems and security protocols

- Recognition and reporting of signature system problems

- Understanding of signature meaning and legal implications

- Regular refresher training and competency verification

Administrator and Support Training:

System administrators require specialized competency in:

- Electronic signature system configuration and maintenance

- User account and role management

- Audit trail monitoring and analysis

- Incident response and problem resolution

- Regulatory compliance verification and documentation

Management and Oversight Training:

Management personnel need understanding of:

- Strategic implications of electronic signature decisions

- Risk assessment and mitigation approaches

- Regulatory compliance monitoring and reporting

- Business continuity and disaster recovery planning

- Vendor management and assessment requirements

Governance Framework Development

Policy and Procedure Development:

Comprehensive governance requires clear policies addressing:

- Electronic signature use cases and approval authorities

- User qualification and training requirements

- System administration and maintenance procedures

- Incident response and problem resolution processes

- Periodic review and update procedures

Risk Management Integration:

Electronic signature governance must integrate with broader quality risk management:

- Regular risk assessment updates reflecting system changes

- Integration with change control and configuration management

- Vendor assessment and ongoing monitoring

- Business continuity and disaster recovery testing

- Regulatory compliance monitoring and reporting

Performance Monitoring and Continuous Improvement:

Effective governance includes ongoing performance management:

- Key performance indicators for signature system effectiveness

- User satisfaction and adoption monitoring

- System reliability and availability tracking

- Regulatory compliance verification and trending

- Continuous improvement process and implementation

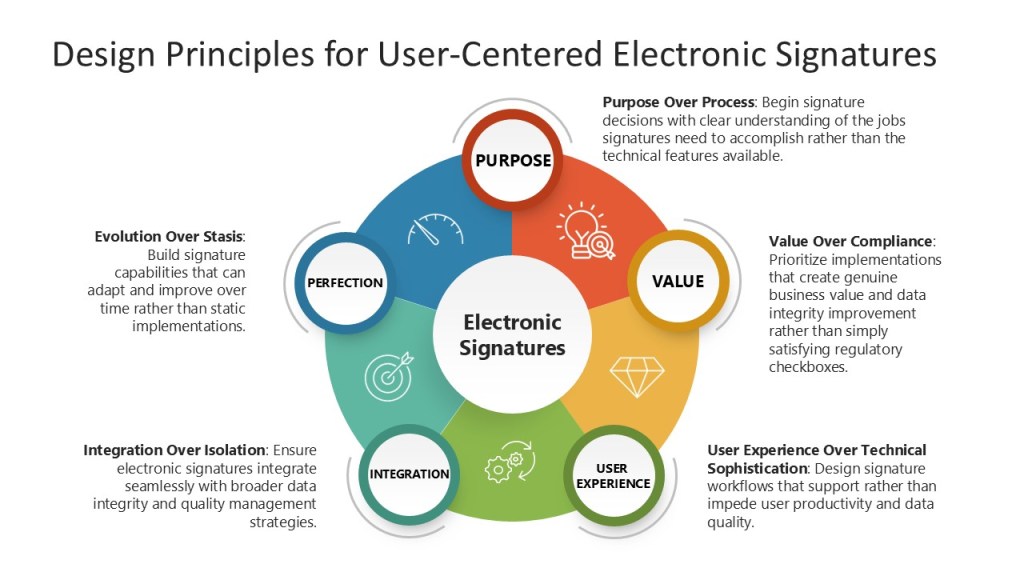

Building Genuine Capability

The ultimate goal of any electronic signature strategy should be building genuine organizational capability rather than simply satisfying regulatory requirements. This requires a fundamental shift in mindset from compliance theater to value creation.

Design Principles for User-Centered Electronic Signatures

Purpose Over Process: Begin signature decisions with clear understanding of the jobs signatures need to accomplish rather than the technical features available.

Value Over Compliance: Prioritize implementations that create genuine business value and data integrity improvement rather than simply satisfying regulatory checkboxes.

User Experience Over Technical Sophistication: Design signature workflows that support rather than impede user productivity and data quality.

Integration Over Isolation: Ensure electronic signatures integrate seamlessly with broader data integrity and quality management strategies.

Evolution Over Stasis: Build signature capabilities that can adapt and improve over time rather than static implementations.

Building Organizational Trust Through Electronic Signatures

Electronic signatures should enhance rather than complicate organizational trust in data integrity. This requires:

- Transparency: Users should understand how electronic signatures protect data integrity and support business decisions.

- Reliability: Signature systems should work consistently and predictably, supporting rather than impeding daily operations.

- Accountability: Electronic signatures should create clear accountability and traceability without overwhelming users with administrative burden.

- Competence: Organizations should demonstrate genuine competence in electronic signature implementation and management, not just regulatory compliance.

Future-Proofing Your Electronic Signature Approach

The regulatory and technological landscape for electronic signatures continues to evolve. Organizations need approaches that can adapt to:

- Regulatory Evolution: Draft revisions to Annex 11, evolving FDA guidance, and new regulatory requirements in emerging markets.

- Technological Advancement: Biometric signatures, blockchain-based authentication, artificial intelligence integration, and mobile signature capabilities.

- Business Model Changes: Remote work, cloud-based systems, global operations, and supplier network integration.

- User Expectations: Consumerization of technology, mobile-first workflows, and seamless user experiences.

The Path Forward: Hiring Electronic Signatures for Real Jobs

We need to move beyond electronic signature systems that create false confidence while providing no genuine data integrity protection. This happens when organizations optimize for regulatory appearance rather than user needs, creating elaborate signature workflows that nobody genuinely wants to hire.

True electronic signature strategy begins with understanding what jobs users actually need accomplished: establishing reliable accountability, protecting data integrity, enabling efficient workflows, and supporting regulatory confidence. Organizations that design electronic signature approaches around these jobs will develop competitive advantages in an increasingly digital world.

The framework presented here provides a structured approach to making these decisions, but the fundamental insight remains: electronic signatures should not be something organizations implement to satisfy auditors. They should be capabilities that organizations actively seek because they make data integrity demonstrably better.

When we design signature capabilities around the jobs users actually need accomplished—protecting data integrity, enabling accountability, streamlining workflows, and building regulatory confidence—we create systems that enhance rather than complicate our fundamental mission of protecting patients and ensuring product quality.

The choice is clear: continue performing electronic signature compliance theater, or build signature capabilities that organizations genuinely want to hire. In a world where data integrity failures can result in patient harm, product recalls, and regulatory action, only the latter approach offers genuine protection.

Electronic signatures should not be something we implement because regulations require them. They should be capabilities we actively seek because they make us demonstrably better at protecting data integrity and serving patients.