The current state of periodic reviews in most pharmaceutical organizations is, to put it charitably, underwhelming. Annual checkbox exercises where teams dutifully document that “the system continues to operate as intended” while avoiding any meaningful analysis of actual system performance, emerging risks, or validation gaps. I’ve seen periodic reviews that consist of little more than confirming the system is still running and updating a few SOPs. This approach might have survived regulatory scrutiny in simpler times, but Section 14 of the draft Annex 11 obliterates this compliance theater and replaces it with rigorous, systematic, and genuinely valuable system intelligence.

The new requirements in the draft Annex 11 Section 14: Periodic Review don’t just raise the bar—they relocate it to a different universe entirely. Where the 2011 version suggested that systems “should be periodically evaluated,” the draft mandates comprehensive, structured, and consequential reviews that must demonstrate continued fitness for purpose and validated state. Organizations that have treated periodic reviews as administrative burdens are about to discover they’re actually the foundation of sustainable digital compliance.

The Philosophical Revolution: From Static Assessment to Dynamic Intelligence

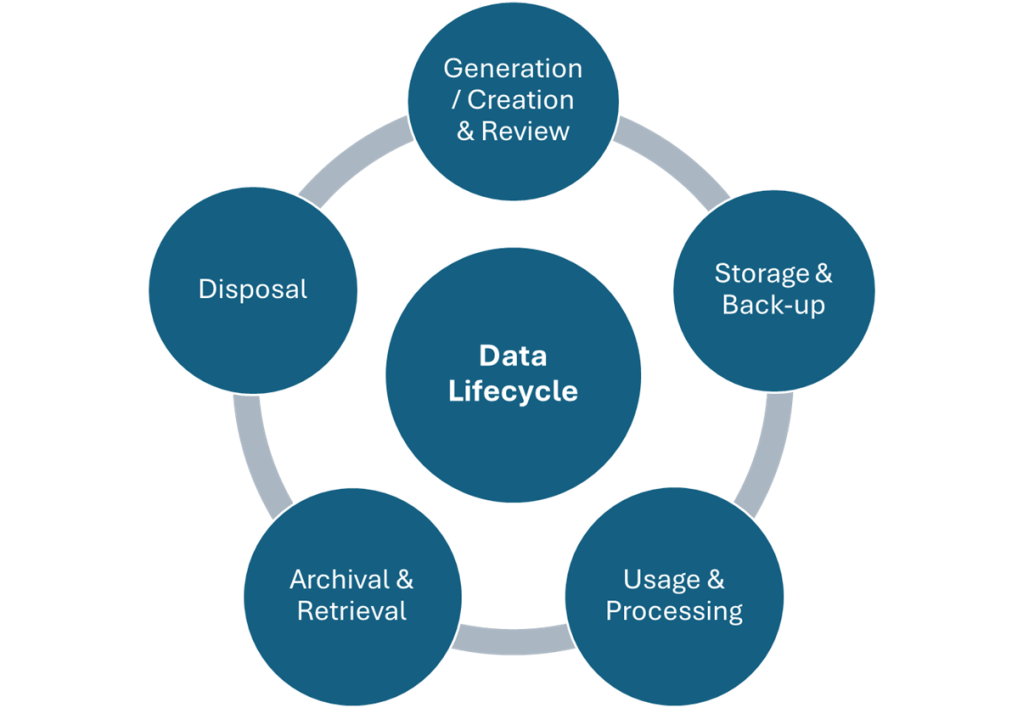

The fundamental transformation in Section 14 reflects a shift from viewing computerized systems as static assets that require occasional maintenance to understanding them as dynamic, evolving components of complex pharmaceutical operations that require continuous intelligence and adaptive management. This philosophical change acknowledges several uncomfortable realities that the industry has long ignored.

First, modern computerized systems never truly remain static. Cloud platforms undergo continuous updates. SaaS providers deploy new features regularly. Integration points evolve. User behaviors change. Regulatory requirements shift. Security threats emerge. Business processes adapt. The fiction that a system can be validated once and then monitored through cursory annual reviews has become untenable in environments where change is the only constant.

Second, the interconnected nature of modern pharmaceutical operations means that changes in one system ripple through entire operational ecosystems in ways that traditional periodic reviews rarely capture. A seemingly minor update to a laboratory information management system might affect data flows to quality management systems, which in turn impact batch release processes, which ultimately influence regulatory reporting. Section 14 acknowledges this complexity by requiring assessment of combined effects across multiple systems and changes.

Third, the rise of data integrity as a central regulatory concern means that periodic reviews must evolve beyond functional assessment to include sophisticated analysis of data handling, protection, and preservation throughout increasingly complex digital environments. This requires capabilities that most current periodic review processes simply don’t possess.

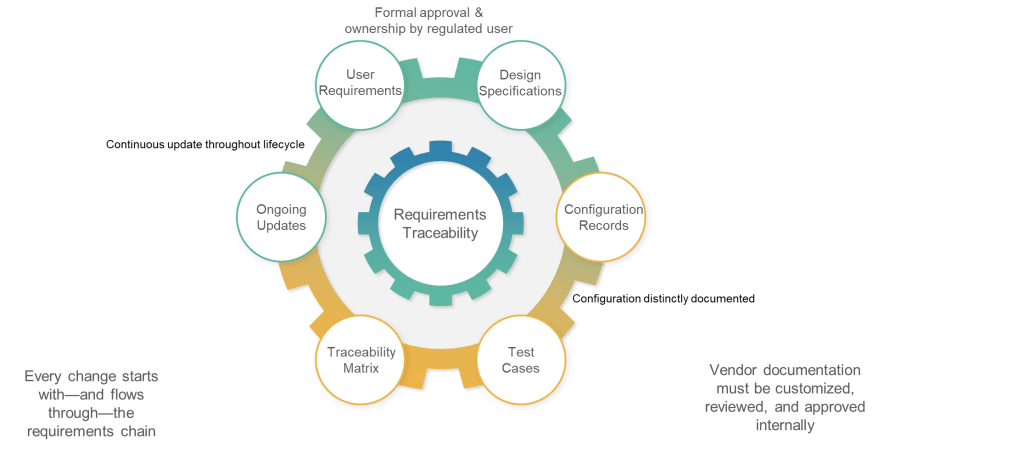

Section 14.1 establishes the foundational requirement that “computerised systems should be subject to periodic review to verify that they remain fit for intended use and in a validated state.” This language moves beyond the permissive “should be evaluated” of the current regulation to establish periodic review as a mandatory demonstration of continued compliance rather than optional best practice.

The requirement that reviews verify systems remain “fit for intended use” introduces a performance-based standard that goes beyond technical functionality to encompass business effectiveness, regulatory adequacy, and operational sustainability. Systems might continue to function technically while becoming inadequate for their intended purposes due to changing regulatory requirements, evolving business processes, or emerging security threats.

Similarly, the requirement to verify systems remain “in a validated state” acknowledges that validation is not a permanent condition but a dynamic state that can be compromised by changes, incidents, or evolving understanding of system risks and requirements. This creates an ongoing burden of proof that validation status is actively maintained rather than passively assumed.

The Twelve Pillars of Comprehensive System Intelligence

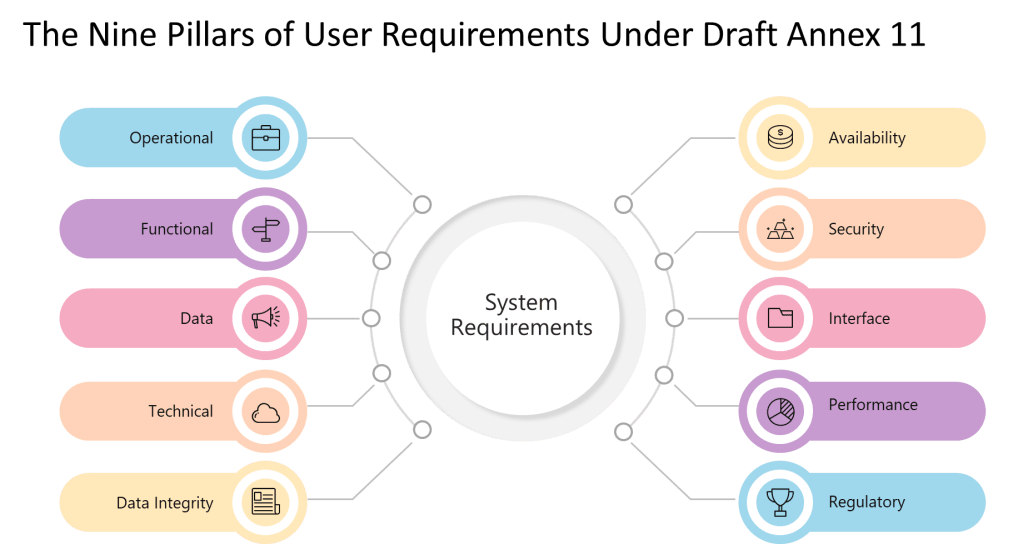

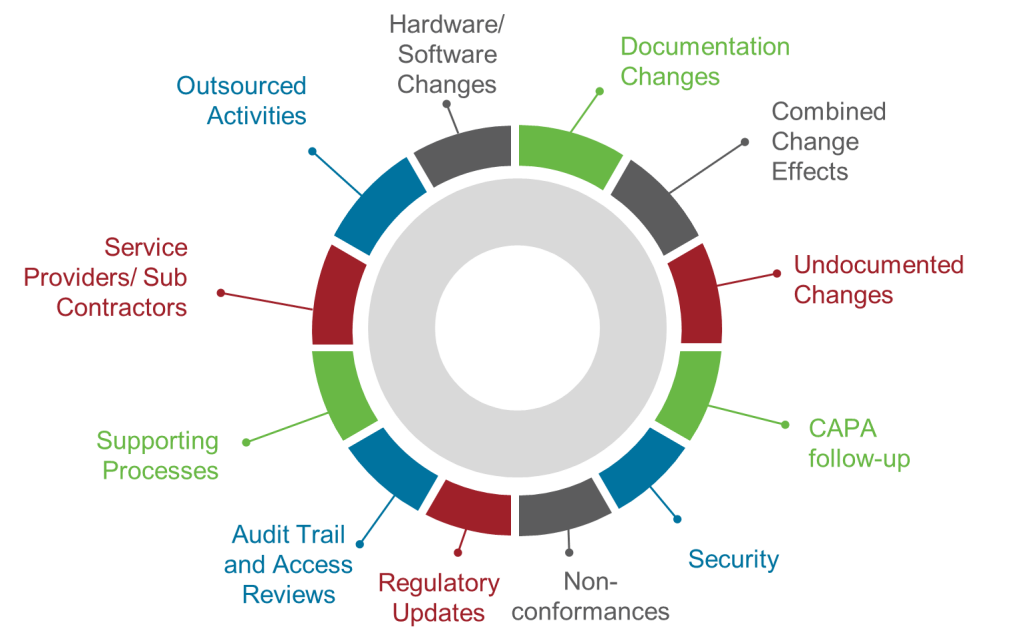

Section 14.2 represents perhaps the most significant transformation in the entire draft regulation by establishing twelve specific areas that must be addressed in every periodic review. This prescriptive approach eliminates the ambiguity that has allowed organizations to conduct superficial reviews while claiming regulatory compliance.

The requirement to assess “changes to hardware and software since the last review” acknowledges that modern systems undergo continuous modification through patches, updates, configuration changes, and infrastructure modifications. Organizations must maintain comprehensive change logs and assess the cumulative impact of all modifications on system validation status, not just changes that trigger formal change control processes.

“Changes to documentation since the last review” recognizes that documentation drift—where procedures, specifications, and validation documents become disconnected from actual system operation—represents a significant compliance risk. Reviews must identify and remediate documentation gaps that could compromise operational consistency or regulatory defensibility.

The requirement to evaluate “combined effect of multiple changes” addresses one of the most significant blind spots in traditional change management approaches. Individual changes might be assessed and approved through formal change control processes, but their collective impact on system performance, validation status, and operational risk often goes unanalyzed. Section 14 requires systematic assessment of how multiple changes interact and whether their combined effect necessitates revalidation activities.

“Undocumented or not properly controlled changes” targets one of the most persistent compliance failures in pharmaceutical operations. Despite robust change control procedures, systems inevitably undergo modifications that bypass formal processes. These might include emergency fixes, vendor-initiated updates, configuration drift, or unauthorized user modifications. Periodic reviews must actively hunt for these changes and assess their impact on validation status.

The focus on “follow-up on CAPAs” integrates corrective and preventive actions into systematic review processes, ensuring that identified issues receive appropriate attention and that corrective measures prove effective over time. This creates accountability for CAPA effectiveness that extends beyond initial implementation to long-term performance.

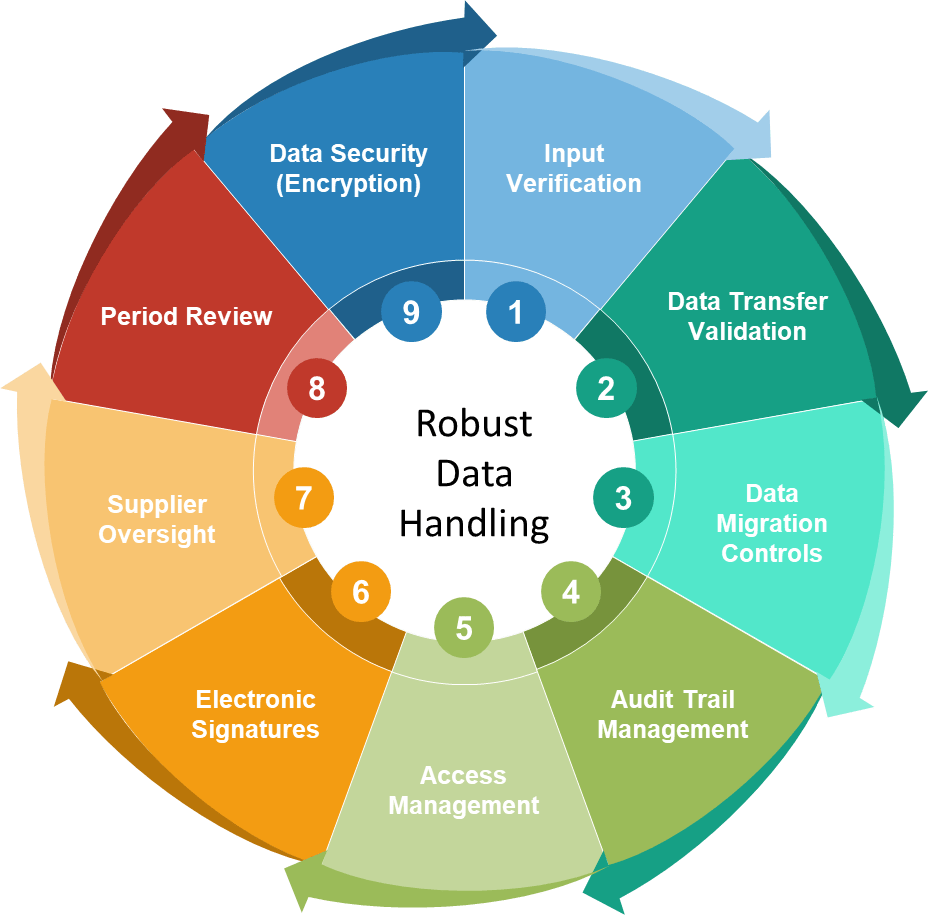

Requirements to assess “security incidents and other incidents” acknowledge that system security and reliability directly impact validation status and regulatory compliance. Organizations must evaluate whether incidents indicate systematic vulnerabilities that require design changes, process improvements, or enhanced controls.

“Non-conformities” assessment requires systematic analysis of deviations, exceptions, and other performance failures to identify patterns that might indicate underlying system inadequacies or operational deficiencies requiring corrective action.

The mandate to review “applicable regulatory updates” ensures that systems remain compliant with evolving regulatory requirements rather than becoming progressively non-compliant as guidance documents are revised, new regulations are promulgated, or inspection practices evolve.

“Audit trail reviews and access reviews” elevates these critical data integrity activities from routine operational tasks to strategic compliance assessments that must be evaluated for effectiveness, completeness, and adequacy as part of systematic periodic review.

Requirements for “supporting processes” assessment acknowledge that computerized systems operate within broader procedural and organizational contexts that directly impact their effectiveness and compliance. Changes to training programs, quality systems, or operational procedures might affect system validation status even when the systems themselves remain unchanged.

The focus on “service providers and subcontractors” reflects the reality that modern pharmaceutical operations depend heavily on external providers whose performance directly impacts system compliance and effectiveness. As I discussed in my analysis of supplier management requirements, organizations cannot outsource accountability for system compliance even when they outsource system operation.

Finally, the requirement to assess “outsourced activities” ensures that organizations maintain oversight of all system-related functions regardless of where they are performed or by whom, acknowledging that regulatory accountability cannot be transferred to external providers.

| Review Area | Primary Objective | Key Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware/Software Changes | Track and assess all system modifications | Change logs, patch management, infrastructure updates, version control |

| Documentation Changes | Ensure documentation accuracy and currency | Document version control, procedure updates, specification accuracy, training materials |

| Combined Change Effects | Evaluate cumulative change impact | Cumulative change impact, system interactions, validation status implications |

| Undocumented Changes | Identify and control unmanaged changes | Change detection, impact assessment, process gap identification, control improvements |

| CAPA Follow-up | Verify corrective action effectiveness | CAPA effectiveness, root cause resolution, preventive measure adequacy, trend analysis |

| Security & Other Incidents | Assess security and reliability status | Incident response effectiveness, vulnerability assessment, security posture, system reliability |

| Non-conformities | Analyze performance and compliance patterns | Deviation trends, process capability, system adequacy, performance patterns |

| Regulatory Updates | Maintain regulatory compliance currency | Regulatory landscape monitoring, compliance gap analysis, implementation planning |

| Audit Trail & Access Reviews | Evaluate data integrity control effectiveness | Data integrity controls, access management effectiveness, monitoring adequacy |

| Supporting Processes | Review supporting organizational processes | Process effectiveness, training adequacy, procedural compliance, organizational capability |

| Service Providers/Subcontractors | Monitor third-party provider performance | Vendor management, performance monitoring, contract compliance, relationship oversight |

| Outsourced Activities | Maintain oversight of external activities | Outsourcing oversight, accountability maintenance, performance evaluation, risk management |

Risk-Based Frequency: Intelligence-Driven Scheduling

Section 14.3 establishes a risk-based approach to periodic review frequency that moves beyond arbitrary annual schedules to systematic assessment of when reviews are needed based on “the system’s potential impact on product quality, patient safety and data integrity.” This approach aligns with broader pharmaceutical industry trends toward risk-based regulatory strategies while acknowledging that different systems require different levels of ongoing attention.

The risk-based approach requires organizations to develop sophisticated risk assessment capabilities that can evaluate system criticality across multiple dimensions simultaneously. A laboratory information management system might have high impact on product quality and data integrity but lower direct impact on patient safety, suggesting different review priorities and frequencies compared to a clinical trial management system or manufacturing execution system.

Organizations must document their risk-based frequency decisions and be prepared to defend them during regulatory inspections. This creates pressure for systematic, scientifically defensible risk assessment methodologies rather than intuitive or political decision-making about resource allocation.

The risk-based approach also requires dynamic adjustment as system characteristics, operational contexts, or regulatory environments change. A system that initially warranted annual reviews might require more frequent attention if it experiences reliability problems, undergoes significant changes, or becomes subject to enhanced regulatory scrutiny.

Risk-Based Periodic Review Matrix

High Criticality Systems

| High Complexity | Medium Complexity | Low Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| FREQUENCY: Quarterly DEPTH: Comprehensive (all 12 pillars) RESOURCES: Dedicated cross-functional team EXAMPLES: Manufacturing Execution Systems, Clinical Trial Management Systems, Integrated Quality Management Platforms FOCUS: Full analytical assessment, trend analysis, predictive modeling | FREQUENCY: Semi-annually DEPTH: Standard+ (emphasis on critical pillars) RESOURCES: Cross-functional team EXAMPLES: LIMS, Batch Management Systems, Electronic Document Management FOCUS: Critical pathway analysis, performance trending, compliance verification | FREQUENCY: Semi-annually DEPTH: Focused+ (critical areas with simplified analysis) RESOURCES: Quality lead + SME support EXAMPLES: Critical Parameter Monitoring, Sterility Testing Systems, Release Testing Platforms FOCUS: Performance validation, data integrity verification, regulatory compliance |

Medium Criticality Systems

| High Complexity | Medium Complexity | Low Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| FREQUENCY: Semi-annually DEPTH: Standard (structured assessment) RESOURCES: Cross-functional team EXAMPLES: Enterprise Resource Planning, Advanced Analytics Platforms, Multi-system Integrations FOCUS: System integration assessment, change impact analysis, performance optimization | FREQUENCY: Annually DEPTH: Standard (balanced assessment) RESOURCES: Small team EXAMPLES: Training Management Systems, Calibration Management, Standard Laboratory Instruments FOCUS: Operational effectiveness, compliance maintenance, trend monitoring | FREQUENCY: Annually DEPTH: Focused (key areas only) RESOURCES: Individual reviewer + occasional SME EXAMPLES: Simple Data Loggers, Basic Trending Tools, Standard Office Applications FOCUS: Basic functionality verification, minimal compliance checking |

High Criticality Systems

| High Complexity | Medium Complexity | Low Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| FREQUENCY: Annually DEPTH: Focused (complexity-driven assessment) RESOURCES: Technical specialist + reviewer EXAMPLES: IT Infrastructure Platforms, Communication Systems, Complex Non-GMP Analytics FOCUS: Technical performance, security assessment, maintenance verification | FREQUENCY: Bi-annually DEPTH: Streamlined (essential checks only) RESOURCES: Individual reviewer EXAMPLES: Facility Management Systems, Basic Inventory Tracking, Simple Reporting Tools FOCUS: Basic operational verification, security updates, essential maintenance | FREQUENCY: Bi-annually or trigger-based DEPTH: Minimal (checklist approach) RESOURCES: Individual reviewer EXAMPLES: Simple Environmental Monitors, Basic Utilities, Non-critical Support Tools FOCUS: Essential functionality, basic security, minimal documentation review |

Documentation and Analysis: From Checklists to Intelligence Reports

Section 14.4 transforms documentation requirements from simple record-keeping to sophisticated analytical reporting that must “document the review, analyze the findings and identify consequences, and be implemented to prevent any reoccurrence.” This language establishes periodic reviews as analytical exercises that generate actionable intelligence rather than administrative exercises that produce compliance artifacts.

The requirement to “analyze the findings” means that reviews must move beyond simple observation to systematic evaluation of what findings mean for system performance, validation status, and operational risk. This analysis must be documented in ways that demonstrate analytical rigor and support decision-making about system improvements, validation activities, or operational changes.

“Identify consequences” requires forward-looking assessment of how identified issues might affect future system performance, compliance status, or operational effectiveness. This prospective analysis helps organizations prioritize corrective actions and allocate resources effectively while demonstrating proactive risk management.

The mandate to implement measures “to prevent any reoccurrence” establishes accountability for corrective action effectiveness that extends beyond traditional CAPA processes to encompass systematic prevention of issue recurrence through design changes, process improvements, or enhanced controls.

These documentation requirements create significant implications for periodic review team composition, analytical capabilities, and reporting systems. Organizations need teams with sufficient technical and regulatory expertise to conduct meaningful analysis and systems capable of supporting sophisticated analytical reporting.

Integration with Quality Management Systems: The Nervous System Approach

Perhaps the most transformative aspect of Section 14 is its integration with broader quality management system activities. Rather than treating periodic reviews as isolated compliance exercises, the new requirements position them as central intelligence-gathering activities that inform broader organizational decision-making about system management, validation strategies, and operational improvements.

This integration means that periodic review findings must flow systematically into change control processes, CAPA systems, validation planning, supplier management activities, and regulatory reporting. Organizations can no longer conduct periodic reviews in isolation from other quality management activities—they must demonstrate that review findings drive appropriate organizational responses across all relevant functional areas.

The integration also means that periodic review schedules must align with other quality management activities including management reviews, internal audits, supplier assessments, and regulatory inspections. Organizations need coordinated calendars that ensure periodic review findings are available to inform these other activities while avoiding duplicative or conflicting assessment activities.

Technology Requirements: Beyond Spreadsheets and SharePoint

The analytical and documentation requirements of Section 14 push most current periodic review approaches beyond their technological limits. Organizations relying on spreadsheets, email coordination, and SharePoint collaboration will find these tools inadequate for systematic multi-system analysis, trend identification, and integrated reporting required by the new regulation.

Effective implementation requires investment in systems capable of aggregating data from multiple sources, supporting collaborative analysis, maintaining traceability throughout review processes, and generating reports suitable for regulatory presentation. These might include dedicated GRC (Governance, Risk, and Compliance) platforms, advanced quality management systems, or integrated validation lifecycle management tools.

The technology requirements extend to underlying system monitoring and data collection capabilities. Organizations need systems that can automatically collect performance data, track changes, monitor security events, and maintain audit trails suitable for periodic review analysis. Manual data collection approaches become impractical when reviews must assess twelve specific areas across multiple systems on risk-based schedules.

Resource and Competency Implications: Building Analytical Capabilities

Section 14’s requirements create significant implications for organizational capabilities and resource allocation. Traditional periodic review approaches that rely on part-time involvement from operational personnel become inadequate for systematic multi-system analysis requiring technical, regulatory, and analytical expertise.

Organizations need dedicated periodic review capabilities that might include full-time coordinators, subject matter expert networks, analytical tool specialists, and management reporting coordinators. These teams need training in analytical methodologies, regulatory requirements, technical system assessment, and organizational change management.

The competency requirements extend beyond technical skills to include systems thinking capabilities that can assess interactions between systems, processes, and organizational functions. Team members need understanding of how changes in one area might affect other areas and how to design analytical approaches that capture these complex relationships.

Comparison with Current Practices: The Gap Analysis

The transformation from current periodic review practices to Section 14 requirements represents one of the largest compliance gaps in the entire draft Annex 11. Most organizations conduct periodic reviews that bear little resemblance to the comprehensive analytical exercises envisioned by the new regulation.

Current practices typically focus on confirming that systems continue to operate and that documentation remains current. Section 14 requires systematic analysis of system performance, validation status, risk evolution, and operational effectiveness across twelve specific areas with documented analytical findings and corrective action implementation.

Current practices often treat periodic reviews as isolated compliance exercises with minimal integration into broader quality management activities. Section 14 requires tight integration with change management, CAPA processes, supplier management, and regulatory reporting.

Current practices frequently rely on annual schedules regardless of system characteristics or operational context. Section 14 requires risk-based frequency determination with documented justification and dynamic adjustment based on changing circumstances.

Current practices typically produce simple summary reports with minimal analytical content. Section 14 requires sophisticated analytical reporting that identifies trends, assesses consequences, and drives organizational decision-making.

GAMP 5 Alignment and Evolution

GAMP 5’s approach to periodic review provides a foundation for implementing Section 14 requirements but requires significant enhancement to meet the new regulatory standards. GAMP 5 recommends periodic review as best practice for maintaining validation throughout system lifecycles and provides guidance on risk-based approaches to frequency determination and scope definition.

However, GAMP 5’s recommendations lack the prescriptive detail and mandatory requirements of Section 14. While GAMP 5 suggests comprehensive system review including technical, procedural, and performance aspects, it doesn’t mandate the twelve specific areas required by Section 14. GAMP 5 recommends formal documentation and analytical reporting but doesn’t establish the specific analytical and consequence identification requirements of the new regulation.

The GAMP 5 emphasis on integration with overall quality management systems aligns well with Section 14 requirements, but organizations implementing GAMP 5 guidance will need to enhance their approaches to meet the more stringent requirements of the draft regulation.

Organizations that have successfully implemented GAMP 5 periodic review recommendations will have significant advantages in transitioning to Section 14 compliance, but they should not assume their current approaches are adequate without careful gap analysis and enhancement planning.

Implementation Strategy: From Current State to Section 14 Compliance

Organizations planning Section 14 implementation must begin with comprehensive assessment of current periodic review practices against the new requirements. This gap analysis should address all twelve mandatory review areas, analytical capabilities, documentation standards, integration requirements, and resource needs.

The implementation strategy should prioritize development of analytical capabilities and supporting technology infrastructure. Organizations need systems capable of collecting, analyzing, and reporting the complex multi-system data required for Section 14 compliance. This typically requires investment in new technology platforms and development of new analytical competencies.

Change management becomes critical for successful implementation because Section 14 requirements represent fundamental changes in how organizations approach system oversight. Stakeholders accustomed to routine annual reviews must be prepared for analytical exercises that might identify significant system issues requiring substantial corrective actions.

Training and competency development programs must address the enhanced analytical and technical requirements of Section 14 while ensuring that review teams understand their integration responsibilities within broader quality management systems.

Organizations should plan phased implementation approaches that begin with pilot programs on selected systems before expanding to full organizational implementation. This allows refinement of procedures, technology, and competencies before deploying across entire system portfolios.

The Final Review Requirement: Planning for System Retirement

Section 14.5 introduces a completely new concept: “A final review should be performed when a computerised system is taken out of use.” This requirement acknowledges that system retirement represents a critical compliance activity that requires systematic assessment and documentation.

The final review requirement addresses several compliance risks that traditional system retirement approaches often ignore. Organizations must ensure that all data preservation requirements are met, that dependent systems continue to operate appropriately, that security risks are properly addressed, and that regulatory reporting obligations are fulfilled.

Final reviews must assess the impact of system retirement on overall operational capabilities and validation status of remaining systems. This requires understanding of system interdependencies that many organizations lack and systematic assessment of how retirement might affect continuing operations.

The final review requirement also creates documentation obligations that extend system compliance responsibilities through the retirement process. Organizations must maintain evidence that system retirement was properly planned, executed, and documented according to regulatory requirements.

Regulatory Implications and Inspection Readiness

Section 14 requirements fundamentally change regulatory inspection dynamics by establishing periodic reviews as primary evidence of continued system compliance and organizational commitment to maintaining validation throughout system lifecycles. Inspectors will expect to see comprehensive analytical reports with documented findings, systematic corrective actions, and clear integration with broader quality management activities.

The twelve mandatory review areas provide inspectors with specific criteria for evaluating periodic review adequacy. Organizations that cannot demonstrate systematic assessment of all required areas will face immediate compliance challenges regardless of overall system performance.

The analytical and documentation requirements create expectations for sophisticated compliance artifacts that demonstrate organizational competency in system oversight and continuous improvement. Superficial reviews with minimal analytical content will be viewed as inadequate regardless of compliance with technical system requirements.

The integration requirements mean that inspectors will evaluate periodic reviews within the context of broader quality management system effectiveness. Disconnected or isolated periodic reviews will be viewed as evidence of inadequate quality system integration and organizational commitment to continuous improvement.

Strategic Implications: Periodic Review as Competitive Advantage

Organizations that successfully implement Section 14 requirements will gain significant competitive advantages through enhanced system intelligence, proactive risk management, and superior operational effectiveness. Comprehensive periodic reviews provide organizational insights that enable better system selection, more effective resource allocation, and proactive identification of improvement opportunities.

The analytical capabilities required for Section 14 compliance support broader organizational decision-making about technology investments, process improvements, and operational strategies. Organizations that develop these capabilities for periodic review purposes can leverage them for strategic planning, performance management, and continuous improvement initiatives.

The integration requirements create opportunities for enhanced organizational learning and knowledge management. Systematic analysis of system performance, validation status, and operational effectiveness generates insights that can improve future system selection, implementation, and management decisions.

Organizations that excel at Section 14 implementation will build reputations for regulatory sophistication and operational excellence that provide advantages in regulatory relationships, business partnerships, and talent acquisition.

The Future of Pharmaceutical System Intelligence

Section 14 represents the evolution of pharmaceutical compliance toward sophisticated organizational intelligence systems that provide real-time insight into system performance, validation status, and operational effectiveness. This evolution acknowledges that modern pharmaceutical operations require continuous monitoring and adaptive management rather than periodic assessment and reactive correction.

The transformation from compliance theater to genuine system intelligence creates opportunities for pharmaceutical organizations to leverage their compliance investments for strategic advantage while ensuring robust regulatory compliance. Organizations that embrace this transformation will build sustainable competitive advantages through superior system management and operational effectiveness.

However, the transformation also creates significant implementation challenges that will test organizational commitment to compliance excellence. Organizations that attempt to meet Section 14 requirements through incremental enhancement of current practices will likely fail to achieve adequate compliance or realize strategic benefits.

Success requires fundamental reimagining of periodic review as organizational intelligence activity that provides strategic value while ensuring regulatory compliance. This requires investment in technology, competencies, and processes that extend well beyond traditional compliance requirements but provide returns through enhanced operational effectiveness and strategic insight.

Summary Comparison: The New Landscape of Periodic Review

| Aspect | Draft Annex 11 Section 14 (2025) | Current Annex 11 (2011) | GAMP 5 Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Mandate | Mandatory periodic reviews to verify system remains “fit for intended use” and “in validated state” | Systems “should be periodically evaluated” – less prescriptive mandate | Strongly recommended as best practice for maintaining validation throughout lifecycle |

| Scope of Review | 12 specific areas mandated including changes, supporting processes, regulatory updates, security incidents | General areas listed: functionality, deviation records, incidents, problems, upgrade history, performance, reliability, security | Comprehensive system review including technical, procedural, and performance aspects |

| Risk-Based Approach | Frequency based on risk assessment of system impact on product quality, patient safety, data integrity | Risk-based approach implied but not explicitly required | Core principle – review depth and frequency based on system criticality and risk |

| Documentation Requirements | Reviews must be documented, findings analyzed, consequences identified, prevention measures implemented | Implicit documentation requirement but not explicitly detailed | Formal documentation recommended with structured reporting |

| Integration with Quality System | Integrated with audits, inspections, CAPA, incident management, security assessments | Limited integration requirements specified | Integrated with overall quality management system and change control |

| Follow-up Actions | Findings must be analyzed to identify consequences and prevent recurrence | No specific follow-up action requirements | Action plans for identified issues with tracking to closure |

| Final System Review | Final review mandated when system taken out of use | No final review requirement specified | Retirement planning and data preservation activities |

The transformation represented by Section 14 marks the end of periodic review as administrative burden and its emergence as strategic organizational capability. Organizations that recognize and embrace this transformation will build sustainable competitive advantages while ensuring robust regulatory compliance. Those that resist will find themselves increasingly disadvantaged in regulatory relationships and operational effectiveness as the pharmaceutical industry evolves toward more sophisticated digital compliance approaches.

Annex 11 Section 14 Integration: Computerized System Intelligence as the Foundation of CPV Excellence

The sophisticated framework for Continuous Process Verification (CPV) methodology and tool selection outlined in this post intersects directly with the revolutionary requirements of Draft Annex 11 Section 14 on periodic review. While CPV focuses on maintaining process validation through statistical monitoring and adaptive control, Section 14 ensures that the computerized systems underlying CPV programs remain in validated states and continue to generate trustworthy data throughout their operational lifecycles.

This intersection represents a critical compliance nexus where process validation meets system validation, creating dependencies that pharmaceutical organizations must understand and manage systematically. The failure to maintain computerized systems in validated states directly undermines CPV program integrity, while inadequate CPV data collection and analysis capabilities compromise the analytical rigor that Section 14 demands.

The Interdependence of System Validation and Process Validation

Modern CPV programs depend entirely on computerized systems for data collection, statistical analysis, trend detection, and regulatory reporting. Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES) capture Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) in real-time. Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) manage Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) testing data. Statistical process control platforms perform the normality testing, capability analysis, and control chart generation that drive CPV decision-making. Enterprise quality management systems integrate CPV findings with broader quality management activities including CAPA, change control, and regulatory reporting.

Section 14’s requirement that computerized systems remain “fit for intended use and in a validated state” directly impacts CPV program effectiveness and regulatory defensibility. A manufacturing execution system that undergoes undocumented configuration changes might continue to collect process data while compromising data integrity in ways that invalidate statistical analysis. A LIMS system with inadequate change control might introduce calculation errors that render capability analyses meaningless. Statistical software with unvalidated updates might generate control charts based on flawed algorithms.

The twelve pillars of Section 14 periodic review map directly onto CPV program dependencies. Hardware and software changes affect data collection accuracy and statistical calculation reliability. Documentation changes impact procedural consistency and analytical methodology validity. Combined effects of multiple changes create cumulative risks to data integrity that traditional CPV monitoring might not detect. Undocumented changes represent blind spots where system degradation occurs without CPV program awareness.

Risk-Based Integration: Aligning System Criticality with Process Impact

The risk-based approach fundamental to both CPV methodology and Section 14 periodic review creates opportunities for integrated assessment that optimizes resource allocation while ensuring comprehensive coverage. Systems supporting high-impact CPV parameters require more frequent and rigorous periodic review than those managing low-risk process monitoring.

Consider an example of a high-capability parameter with data clustered near LOQ requiring threshold-based alerts rather than traditional control charts. The computerized systems supporting this simplified monitoring approach—perhaps basic trending software with binary alarm capabilities—represent lower validation risk than sophisticated statistical process control platforms. Section 14’s risk-based frequency determination should reflect this reduced complexity, potentially extending review cycles while maintaining adequate oversight.

Conversely, systems supporting critical CPV parameters with complex statistical requirements—such as multivariate analysis platforms monitoring bioprocess parameters—warrant intensive periodic review given their direct impact on patient safety and product quality. These systems require comprehensive assessment of all twelve pillars with particular attention to change management, analytical method validation, and performance monitoring.

The integration extends to tool selection methodologies outlined in the CPV framework. Just as process parameters require different statistical tools based on data characteristics and risk profiles, the computerized systems supporting these tools require different validation and periodic review approaches. A system supporting simple attribute-based monitoring requires different periodic review depth than one performing sophisticated multivariate statistical analysis.

Data Integrity Convergence: CPV Analytics and System Audit Trails

Section 14’s emphasis on audit trail reviews and access reviews creates direct synergies with CPV data integrity requirements. The sophisticated statistical analyses required for effective CPV—including normality testing, capability analysis, and trend detection—depend on complete, accurate, and unaltered data throughout collection, storage, and analysis processes.

The framework’s discussion of decoupling analytical variability from process signals requires systems capable of maintaining separate data streams with independent validation and audit trail management. Section 14’s requirement to assess audit trail review effectiveness directly supports this CPV capability by ensuring that system-generated data remains traceable and trustworthy throughout complex analytical workflows.

Consider the example where threshold-based alerts replaced control charts for parameters near LOQ. This transition requires system modifications to implement binary logic, configure alert thresholds, and generate appropriate notifications. Section 14’s focus on combined effects of multiple changes ensures that such CPV-driven system modifications receive appropriate validation attention while the audit trail requirements ensure that the transition maintains data integrity throughout implementation.

The integration becomes particularly important for organizations implementing AI-enhanced CPV tools or advanced analytics platforms. These systems require sophisticated audit trail capabilities to maintain transparency in algorithmic decision-making while Section 14’s periodic review requirements ensure that AI model updates, training data changes, and algorithmic modifications receive appropriate validation oversight.

Living Risk Assessments: Dynamic Integration of System and Process Intelligence

The framework’s emphasis on living risk assessments that integrate ongoing data with periodic review cycles aligns perfectly with Section 14’s lifecycle approach to system validation. CPV programs generate continuous intelligence about process performance, parameter behavior, and statistical tool effectiveness that directly informs system validation decisions.

Process capability changes detected through CPV monitoring might indicate system performance degradation requiring investigation through Section 14 periodic review. Statistical tool effectiveness assessments conducted as part of CPV methodology might reveal system limitations requiring configuration changes or software updates. Risk profile evolution identified through living risk assessments might necessitate changes to Section 14 periodic review frequency or scope.

This dynamic integration creates feedback loops where CPV findings drive system validation decisions while system validation ensures CPV data integrity. Organizations must establish governance structures that facilitate information flow between CPV teams and system validation functions while maintaining appropriate independence in decision-making processes.

Implementation Framework: Integrating Section 14 with CPV Excellence

Organizations implementing both sophisticated CPV programs and Section 14 compliance should develop integrated governance frameworks that leverage synergies while avoiding duplication or conflicts. This requires coordinated planning that aligns system validation cycles with process validation activities while ensuring both programs receive adequate resources and management attention.

The implementation should begin with comprehensive mapping of system dependencies across CPV programs, identifying which computerized systems support which CPV parameters and analytical methods. This mapping drives risk-based prioritization of Section 14 periodic review activities while ensuring that high-impact CPV systems receive appropriate validation attention.

System validation planning should incorporate CPV methodology requirements including statistical software validation, data integrity controls, and analytical method computerization. CPV tool selection decisions should consider system validation implications including ongoing maintenance requirements, change control complexity, and periodic review resource needs.

Training programs should address the intersection of system validation and process validation requirements, ensuring that personnel understand both CPV statistical methodologies and computerized system compliance obligations. Cross-functional teams should include both process validation experts and system validation specialists to ensure decisions consider both perspectives.

Strategic Advantage Through Integration

Organizations that successfully integrate Section 14 system intelligence with CPV process intelligence will gain significant competitive advantages through enhanced decision-making capabilities, reduced compliance costs, and superior operational effectiveness. The combination creates comprehensive understanding of both process and system performance that enables proactive identification of risks and opportunities.

Integrated programs reduce resource requirements through coordinated planning and shared analytical capabilities while improving decision quality through comprehensive risk assessment and performance monitoring. Organizations can leverage system validation investments to enhance CPV capabilities while using CPV insights to optimize system validation resource allocation.

The integration also creates opportunities for enhanced regulatory relationships through demonstration of sophisticated compliance capabilities and proactive risk management. Regulatory agencies increasingly expect pharmaceutical organizations to leverage digital technologies for enhanced quality management, and the integration of Section 14 with CPV methodology demonstrates commitment to digital excellence and continuous improvement.

This integration represents the future of pharmaceutical quality management where system validation and process validation converge to create comprehensive intelligence systems that ensure product quality, patient safety, and regulatory compliance through sophisticated, risk-based, and continuously adaptive approaches. Organizations that master this integration will define industry best practices while building sustainable competitive advantages through operational excellence and regulatory sophistication.