The pharmaceutical industry’s approach to supplier management has operated on a comfortable fiction for decades: as long as you had a signed contract and conducted an annual questionnaire review, regulatory responsibility somehow transferred to your vendors. That cozy delusion is shattered to a surprising degree in the new Section 7 of the draft Annex 11, which reads like a regulatory autopsy of every failed outsourcing arrangement that ever derailed a drug approval or triggered a warning letter.

If you’ve been following my earlier breakdowns of the draft Annex 11 overhaul, you know this isn’t incremental tinkering. The regulators are systematically dismantling every assumption about digital compliance that pharmaceutical companies have built their strategies around. Nowhere is this more evident than in Section 7, which transforms supplier management from a procurement afterthought into the backbone of GxP data integrity.

The new requirements don’t just raise the bar—they relocate it to a different planet entirely. Organizations that treat vendor management as a checkbox exercise are about to discover that their carefully constructed compliance programs have been built on quicksand. The draft makes one thing crystal clear: you cannot outsource responsibility, only tasks. Every cloud service, every SaaS platform, every IT support contract becomes a direct extension of your quality management system, subject to the same scrutiny as your in-house operations.

This represents more than regulatory updating. Section 7 acknowledges that modern pharmaceutical operations depend fundamentally on external providers—from cloud infrastructure underpinning LIMS systems to SaaS platforms managing clinical data to third-party IT support maintaining manufacturing execution systems. The old model of “trust but check-in once a year” has been replaced with “prove it, continuously, or prepare for the consequences.”

The Regulatory Context: Why Section 7 Emerged

The current Annex 11, published in 2011, addresses suppliers through a handful of brief clauses that seem almost quaint in retrospect. Section 3 requires “formal agreements” with “clear statements of responsibilities” and suggests that “competence and reliability” should guide supplier selection. The audit requirement appears as a single sentence recommending risk-based assessment. That’s it. Five sentences to govern relationships that now determine whether pharmaceutical companies can manufacture products, release batches, or maintain regulatory compliance.

As digital transformation accelerated throughout the pharmaceutical industry, the guidance became increasingly outdated. Organizations moved core GMP functions to cloud platforms, implemented SaaS quality management systems, and relied increasingly on external IT support—all while operating under regulatory guidance designed for a world where “computerized systems” meant locally installed software running on company-owned hardware.

The regulatory wake-up call came through a series of high-profile data integrity failures, cybersecurity breaches, and compliance failures that traced directly to inadequate supplier oversight. Warning letters began citing “failure to ensure that service providers meet applicable requirements” and “inadequate oversight of computerized system suppliers.” Inspection findings revealed organizations that couldn’t explain how their cloud providers managed data, couldn’t access their audit trails, and couldn’t demonstrate control over systems essential to product quality.

Section 7 represents the regulatory response to this systemic failure. The draft Annex 11 approaches supplier management with the same rigor previously reserved for manufacturing processes, recognizing that in digitized pharmaceutical operations, the distinction between internal and external systems has become largely meaningless from a compliance perspective.

Dissecting Section 7: The Five Subsections That Change Everything

7.1 Responsibility: The Death of Liability Transfer

The opening salvo of Section 7 eliminates any ambiguity about accountability: “When a regulated user is relying on a vendor’s qualification of a system used in GMP activities, a service provider, or an internal IT department’s qualification and/or operation of such system, this does not change the requirements put forth in this document. The regulated user remains fully responsible for these activities based on the risk they constitute on product quality, patient safety and data integrity.”

TThis language represents a fundamental shift from the permissive approach of the 2011 version. Organizations can no longer treat outsourcing as risk transfer. Whether you’re using Amazon Web Services to host your quality management system, Microsoft Azure to run your clinical data platform, or a specialized pharmaceutical SaaS provider for batch record management, you remain fully accountable for ensuring those systems meet every requirement specified in Annex 11.

The practical implications are staggering. Organizations that have structured their compliance programs around the assumption that “the vendor handles validation” must completely reconceptualize their approach. Cloud service providers don’t become exempt from GxP requirements simply because they’re external entities. SaaS platforms can’t claim immunity from data integrity standards because they serve multiple industries. Every system that touches GMP activities becomes subject to the same validation, documentation, and control requirements regardless of where it operates or who owns the infrastructure.

This requirement also extends to internal IT departments, acknowledging that many pharmaceutical organizations have tried to create an artificial separation between quality functions and IT support. The draft eliminates this distinction, making clear that IT departments supporting GMP activities are subject to the exact oversight requirements as external service providers.

The responsibility clause creates particular challenges for organizations using multi-tenant SaaS platforms, where multiple pharmaceutical companies share infrastructure and applications. The regulated user cannot claim that shared tenancy dilutes their responsibility or that other tenants’ activities absolve them of compliance obligations. Each organization must demonstrate control and oversight as if it were the sole user of the system.

7.2 Audit: Risk-Based Assessment That Actually Means Something

Section 7.2 transforms supplier auditing from an optional risk management exercise into a structured compliance requirement: “When a regulated user is relying on a vendor’s or a service provider’s qualification and/or operation of a system used in GMP activities, the regulated user should, according to risk and system criticality, conduct an audit or a thorough assessment to determine the adequacy of the vendor or service provider’s implemented procedures, the documentation associated with the deliverables, and the potential to leverage these rather than repeating the activities.”

The language “according to risk and system criticality” establishes a scalable framework that requires organizations to classify their systems and adjust audit rigor accordingly. A cloud-based LIMS managing batch release testing demands different scrutiny than a SaaS platform used for training record management. However, the draft makes clear that risk-based does not mean risk-free—even lower-risk systems require documented assessment to justify reduced audit intensity.

The phrase “thorough assessment” provides flexibility for organizations that cannot conduct traditional on-site audits of major cloud providers like AWS or Microsoft. However, it establishes a burden of proof requiring organizations to demonstrate that their assessment methodology provides equivalent assurance to traditional auditing approaches. This might include reviewing third-party certifications, analyzing security documentation, or conducting remote assessments of provider capabilities.

The requirement to evaluate “potential to leverage” supplier documentation acknowledges the reality that many cloud providers and SaaS vendors have invested heavily in GxP-compliant infrastructure and documentation. Organizations can potentially reduce their validation burden by demonstrating that supplier qualifications meet regulatory requirements, but they must affirmatively prove this rather than simply assuming it.

For organizations managing dozens or hundreds of supplier relationships, the audit requirement creates significant resource implications. Companies must develop risk classification methodologies, train audit teams on digital infrastructure assessment, and establish ongoing audit cycles that account for the dynamic nature of cloud services and SaaS platforms.

7.3 Oversight: SLAs and KPIs That Actually Matter

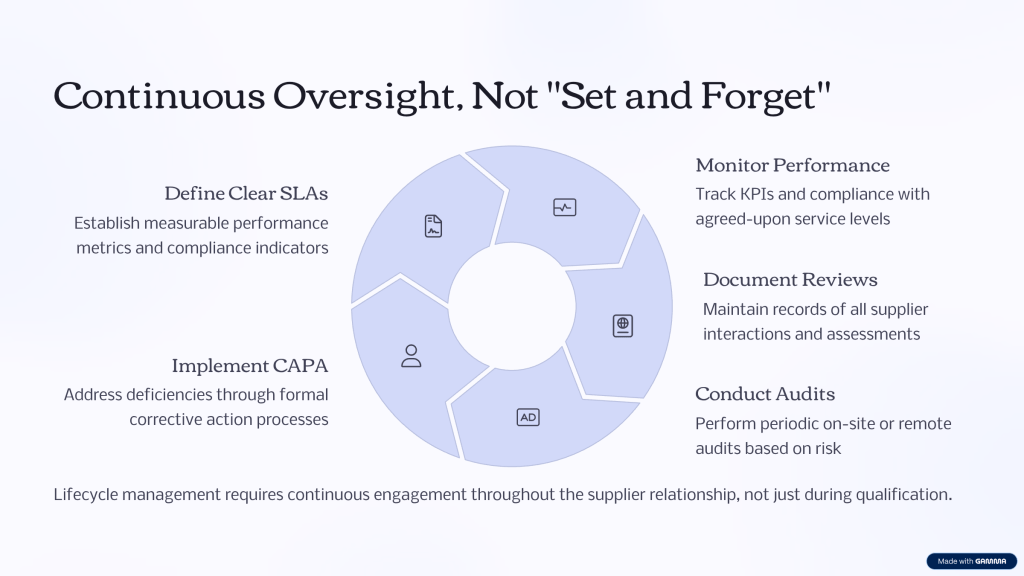

The oversight requirement in Section 7.3 mandates active, continuous supplier management rather than passive relationship maintenance: “When a regulated user is relying on a service provider’s or an internal IT department’s operation of a system used in GMP activities, the regulated user should exercise effective oversight of this according to defined service level agreements (SLA) and key performance indicators (KPI) agreed with the service provider or the internal IT department.”

This requirement acknowledges that traditional supplier management approaches, based on annual reviews and incident-driven interactions, are inadequate for managing dynamic digital services. Cloud platforms undergo continuous updates. SaaS providers deploy new features regularly. Infrastructure changes occur without direct customer notification. The oversight requirement establishes expectations for real-time monitoring and proactive management of these relationships.

The emphasis on “defined” SLAs and KPIs means organizations cannot rely on generic service level commitments provided by suppliers. Instead, they must negotiate specific metrics aligned with GMP requirements and data integrity objectives. For a cloud-based manufacturing execution system, relevant KPIs might include system availability during manufacturing campaigns, data backup completion rates, and incident response times for GMP-critical issues.

Effective oversight requires organizations to establish monitoring systems capable of tracking supplier performance against agreed metrics. This might involve automated dashboard monitoring of system availability, regular review of supplier-provided performance reports, or integration of supplier metrics into internal quality management systems. The goal is continuous visibility into supplier performance rather than retrospective assessment during periodic reviews.

The requirement also applies to internal IT departments, recognizing that many pharmaceutical organizations struggle with accountability when GMP systems are managed by IT teams that don’t report to quality functions. The draft requires the same SLA and KPI framework for internal providers, establishing clear performance expectations and accountability mechanisms.

Evaluating KPIs for IT Service Providers

When building a system of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for supplier and service management in a GxP-regulated environment you will want KPIs that truly measure your suppliers’ performance and your own ability to maintain control and regulatory compliance. Since the new requirements emphasize continuous oversight, risk-based evaluation, and lifecycle management, KPIs should cover not just commercial performance but all areas of GxP relevance.

Here are supplier KPIs that are practical, defensible, and ready to justify in both quality forums and to auditors:

1. System Availability/Uptime

Measures the percentage of time your supplier’s system or service is fully operational during agreed business hours (or 24/7 for critical GMP systems).

Target: 99.9% uptime for critical systems.

2. Incident Response Time

Average or maximum time elapsed between a reported incident (especially those affecting GMP/data integrity) and initial supplier response.

Target: Immediate acknowledgment; <4 hours for GMP-impacting incidents.

3. Incident Resolution/Recovery Time

Average time taken to fully resolve GMP-critical incidents and restore compliant operations.

Target: <24 hours for resolution, with root cause and preventive action documented.

4. Change Notification Timeliness

Measures whether the supplier notifies you of planned changes, updates, or upgrades within the contractually required timeframe before implementation.

Target: 100% advance notification as per contract (e.g., 30 days for non-critical, 48 hours for critical updates).

5. Data Backup Success Rate

Percentage of scheduled backups completed successfully and verified for integrity.

Target: 100% for GMP-relevant data.

6. Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) Closure Rate

Percentage of supplier-driven CAPA actions (arising from audits, incidents, or performance monitoring) closed on time.

Target: 95% closed within agreed timelines.

7. Audit Finding Closure Timeliness

Measures time from audit finding notification to completed remediation (agreed corrective action implemented and verified).

Target: 100% of critical findings closed within set period (e.g., 30 days).

8. Percentage of Deliverables On-Time

For services involving defined deliverables (e.g., validation documentation, periodic reports)—what percentage arrive within agreed deadlines.

Target: 98–100%.

9. Compliance with Change Control

Rate at which supplier’s changes (software, hardware, infrastructure) are processed in accordance with your approved change control system—including proper notification, documentation, and assessment.

Target: 100% compliance.

10. Regulatory/SLA Audit Support Satisfaction

Measured by feedback (internal or from inspectors) on supplier’s effectiveness and readiness in supporting regulatory or SLA-related audits.

Target: 100% “satisfactory.”

11. Security Event/Incident Rate

Number of security events or potential data integrity breaches attributable to the supplier per reporting period.

Target: Zero for GMP-impacting events; rapid supplier notification if any occur.

12. Service Request Resolution Rate

Percentage of service/support requests (tickets) resolved within the defined response and resolution SLAs.

Target: 98%+.

13. Documentation Accessibility Rate

Percentage of required documentation (validation packages, SOPs, certifications, audit trails) available on demand (especially during inspection readiness checks).

Target: 100%.

14. Training Completion Rate for Supplier Personnel

Percentage of supplier team members assigned to your contract who have successfully completed required GxP and data integrity training.

Target: 100%.

To be Annex 11 ready, always align your KPIs with your supplier’s contract (including SLAs/KPIs written into the agreement). Track these metrics and trend them over time—continual improvement and transparency are expected.

Also, regularly review and risk-assess your chosen KPIs: as the risk profile of the supplier or service changes, update the KPIs and targets, and ensure they are embedded into your supplier oversight, quality management review, and audit processes. This forms a defensible part of your data integrity and supplier management evidence under the upcoming draft Annex 11.

7.4 Documentation Availability: No More “Black Box” Services

Section 7.4 addresses one of the most persistent challenges in modern supplier management—ensuring access to documentation needed for regulatory compliance: “When a regulated user relies on a vendor’s, a service provider’s or an internal IT department’s qualification and/or operation of a system used in GMP activities, the regulated user should ensure that documentation for activities required in this document is accessible and can be explained from their facility.”

The phrase “accessible and can be explained” establishes two distinct requirements. Documentation must be physically or electronically available when needed, but organizations must also maintain sufficient understanding to explain systems and processes to regulatory inspectors. This eliminates the common practice of simply collecting supplier documentation without ensuring internal teams understand its contents and implications.

For cloud-based systems, this requirement creates particular challenges. Major cloud providers like AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud offer extensive documentation about their infrastructure and services, but pharmaceutical companies must identify which documents are relevant to their specific GMP applications and ensure they can explain how cloud architecture supports data integrity and system reliability.

SaaS providers typically provide less detailed technical documentation, focusing instead on user guides and administrative procedures. Organizations must work with suppliers to obtain validation documentation, system architecture information, and technical specifications needed to demonstrate compliance. This often requires negotiating specific documentation requirements into service agreements rather than accepting standard documentation packages.

The requirement that documentation be explainable “from their facility” means organizations cannot simply reference supplier documentation during inspections. Internal teams must understand system architecture, data flows, security controls, and validation approaches well enough to explain them without direct supplier support. This necessitates significant knowledge transfer from suppliers and ongoing training for internal personnel.

7.5 Contracts: From Legal Formalities to GMP Control Documents

The final subsection transforms supplier contracts from legal formalities into operational control documents: “When a regulated user is relying on a service provider’s or an internal IT department’s qualification and/or operation of a system used in GMP activities, the regulated user should have a contract with a service provider or have approved procedures with an internal IT department which: i. Describes the activities and documentation to be provided ii. Establishes the company procedures and regulatory requirements to be met iii. Agrees on regular, ad hoc and incident reporting and oversight (incl. SLAs and KPIs), answer times, resolution times, etc. iv. Agrees on conditions for supplier audits v. Agrees on support during regulatory inspections, if so requested”

This contract framework establishes five essential elements that transform supplier agreements from commercial documents into GMP control mechanisms. Each element addresses specific compliance risks that have emerged as pharmaceutical organizations increased their reliance on external providers.

Activities and Documentation (7.5.i): This requirement ensures contracts specify exactly what work will be performed and what documentation will be provided. Generic service descriptions become inadequate when regulatory compliance depends on specific activities being performed to defined standards. For a cloud infrastructure provider, this might specify data backup procedures, security monitoring activities, and incident response protocols. For a SaaS platform, it might detail user access management, audit trail generation, and data export capabilities.

Regulatory Requirements (7.5.ii): Contracts must explicitly establish which regulatory requirements apply to supplier activities and how compliance will be demonstrated. This eliminates ambiguity about whether suppliers must meet GxP standards and establishes accountability for regulatory compliance. Suppliers cannot claim ignorance of pharmaceutical requirements, and regulated companies cannot assume suppliers understand applicable standards without explicit contractual clarification.

Reporting and Oversight (7.5.iii): The requirement for “regular, ad hoc and incident reporting” establishes expectations for ongoing communication beyond standard commercial reporting. Suppliers must provide performance data, incident notifications, and ad hoc reports needed for effective oversight. The specification of “answer times” and “resolution times” ensures suppliers commit to response standards aligned with GMP operational requirements rather than generic commercial service levels.

Audit Conditions (7.5.iv): Contracts must establish explicit audit rights and conditions, eliminating supplier claims that audit activities exceed contractual scope. This is particularly important for cloud providers and SaaS vendors who serve multiple industries and may resist pharmaceutical-specific audit requirements. The contractual audit framework must specify frequency, scope, access rights, and supplier support obligations.

Regulatory Inspection Support (7.5.v): Perhaps the most critical requirement, contracts must establish supplier obligations to support regulatory inspections “if so requested.” This cannot be optional or subject to additional fees—it must be a contractual obligation. Suppliers must commit to providing documentation, expert testimony, and system demonstrations needed during regulatory inspections. For cloud providers, this might include architectural diagrams and security certifications. For SaaS vendors, it might include system demonstrations and user access reports.

The Cloud Provider Challenge: Managing Hyperscale Relationships

Section 7’s requirements create particular challenges for organizations using hyperscale cloud providers like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform. These providers serve thousands of customers across multiple industries and typically resist customization of their standard service agreements and operational procedures. However, the draft Annex 11 requirements apply regardless of provider size or market position.

Shared Responsibility Models: Cloud providers operate on shared responsibility models where customers retain responsibility for data, applications, and user access while providers manage infrastructure, physical security, and basic services. Section 7 requires pharmaceutical companies to understand and document these responsibility boundaries clearly, ensuring no compliance gaps exist between customer and provider responsibilities.

Standardized Documentation: Hyperscale providers offer extensive documentation about their services, security controls, and compliance certifications. However, pharmaceutical companies must identify which documents are relevant to their specific GMP applications and ensure they understand how provider capabilities support their compliance obligations. This often requires significant analysis of provider documentation to extract GMP-relevant information.

Audit Rights: Traditional audit rights are generally not available with hyperscale cloud providers, who instead offer third-party certifications and compliance reports. Organizations must develop alternative assessment methodologies that satisfy Section 7.2 requirements while acknowledging the realities of cloud provider business models. This might include relying on SOC 2 Type II reports, ISO 27001 certifications, and specialized GxP assessments provided by the cloud provider.

Service Level Agreements: Cloud providers offer standard SLAs focused on technical performance metrics like availability and response times. Pharmaceutical companies must ensure these standard metrics align with GMP requirements or negotiate additional commitments. For example, standard 99.9% availability commitments may be inadequate for systems supporting continuous manufacturing operations.

Incident Response: Cloud provider incident response procedures focus on technical service restoration rather than GMP impact assessment. Organizations must establish internal procedures to evaluate the GMP implications of cloud incidents and ensure appropriate notifications and investigations occur even when the underlying technical issues are resolved by the provider.

SaaS Platform Management: Beyond Standard IT Procurement

Software-as-a-Service platforms present unique challenges under Section 7 because they combine infrastructure management with application functionality, often operated by providers with limited pharmaceutical industry experience. Unlike hyperscale cloud providers who focus purely on infrastructure, SaaS vendors make decisions about application design, user interface, and business workflows that directly impact GMP compliance.

Validation Dependencies: SaaS platforms undergo continuous development and deployment cycles that can affect GMP functionality without customer involvement. Section 7 requires organizations to maintain oversight of these changes and ensure ongoing validation despite dynamic platform evolution. This necessitates change control procedures that account for supplier-initiated modifications and validation strategies that accommodate continuous deployment models.

Data Integrity Controls: SaaS platforms must implement audit trail capabilities, user access controls, and data integrity measures aligned with ALCOA+ principles. However, many platforms designed for general business use lack pharmaceutical-specific features. Organizations must work with suppliers to ensure platform capabilities support GMP requirements or implement compensating controls to address gaps.

Multi-Tenant Considerations: Most SaaS platforms operate in multi-tenant environments where multiple customers share application instances and infrastructure. This creates unique challenges for demonstrating data segregation, ensuring audit trail integrity, and maintaining security controls. Organizations must understand multi-tenant architecture and verify that other tenants cannot access or affect their GMP data.

Integration Management: SaaS platforms typically integrate with other systems through APIs and data feeds that may not be under direct pharmaceutical company control. Section 7 oversight requirements extend to these integrations, requiring organizations to understand data flows, validation status, and change control procedures for all connected systems.

Exit Strategies: The draft Annex 11 implications include requirements for data retrieval and system discontinuation procedures. SaaS contracts must specify data export capabilities, retention periods, and migration support to ensure organizations can maintain compliance during platform transitions.

Internal IT Department Transformation

One of the most significant aspects of Section 7 is its explicit inclusion of internal IT departments within the supplier management framework. This acknowledges the reality that many pharmaceutical organizations have created artificial separations between quality functions and IT support, leading to unclear accountability and inadequate oversight of GMP-critical systems.

Procedural Requirements: The draft requires “approved procedures” with internal IT departments that mirror the contractual requirements applied to external suppliers. This means IT departments must operate under documented procedures that specify their GMP responsibilities, performance expectations, and accountability mechanisms.

SLA Framework: Internal IT departments must commit to defined service level agreements and key performance indicators just like external suppliers. This eliminates the informal, best-effort support models that many organizations have relied upon for internal IT services. IT departments must commit to specific response times, availability targets, and resolution procedures for GMP-critical systems.

Audit and Oversight: Quality organizations must implement formal oversight processes for internal IT departments, including regular performance reviews, capability assessments, and compliance evaluations. This may require establishing new organizational relationships and reporting structures to ensure appropriate independence and accountability.

Change Management: Internal IT departments must implement change control procedures that align with GMP requirements rather than general IT practices. This includes impact assessment procedures, testing requirements, and approval processes that account for potential effects on product quality and data integrity.

Documentation Standards: IT departments must maintain documentation to the same standards required of external suppliers, including system architecture documents, validation records, and operational procedures. This often requires significant upgrades to IT documentation practices and knowledge management systems.

Risk-Based Implementation Strategy

Section 7’s risk-based approach requires organizations to develop systematic methodologies for classifying suppliers and systems, determining appropriate oversight levels, and allocating management resources effectively. This represents a significant departure from one-size-fits-all approaches that many organizations have used for supplier management.

System Criticality Assessment: Organizations must classify their computerized systems based on impact to product quality, patient safety, and data integrity. This classification drives the intensity of supplier oversight, audit requirements, and contractual controls. Critical systems like manufacturing execution systems and laboratory information management systems require the highest level of supplier management, while lower-impact systems like general productivity applications may warrant less intensive oversight.

Supplier Risk Profiling: Different types of suppliers present different risk profiles that affect management approaches. Hyperscale cloud providers typically have robust infrastructure and security controls but limited pharmaceutical industry knowledge. Specialized pharmaceutical software vendors understand GxP requirements but may have less mature operational capabilities. Contract research organizations have pharmaceutical expertise but variable quality systems. Organizations must develop supplier-specific management strategies that account for these different risk profiles.

Audit Planning: Risk-based audit planning requires organizations to prioritize audit activities based on system criticality, supplier risk, and business impact. High-risk suppliers supporting critical systems require comprehensive audits, while lower-risk relationships may be managed through document reviews and remote assessments. Organizations must develop audit scheduling that ensures adequate coverage while managing resource constraints.

Performance Monitoring: Risk-based monitoring means different suppliers require different levels of ongoing oversight. Critical suppliers need real-time performance monitoring and frequent review cycles, while lower-risk suppliers may be managed through periodic assessments and exception reporting. Organizations must implement monitoring systems that provide appropriate visibility without creating excessive administrative burden.

Data Ownership and Access Rights

Section 7’s requirements for clear data ownership and access rights address one of the most contentious issues in modern supplier relationships. Many cloud providers and SaaS vendors have terms of service that create ambiguity about data ownership, retention rights, and access capabilities that are incompatible with GMP requirements.

Ownership Clarity: Contracts must explicitly establish that pharmaceutical companies retain full ownership of all GMP data regardless of where it is stored or processed. This includes not only direct manufacturing and quality data but also metadata, audit trails, and system configuration information. Suppliers cannot claim any ownership rights or use licenses that could affect data availability or integrity.

Access Rights: Pharmaceutical companies must maintain unrestricted access to their data for regulatory purposes, internal investigations, and business operations. This includes both standard data access through application interfaces and raw data access for migration or forensic purposes. Suppliers cannot impose restrictions on data access that could interfere with regulatory compliance or business continuity.

Retention Requirements: Contracts must specify data retention periods that align with pharmaceutical industry requirements rather than supplier standard practices. GMP data may need to be retained for decades beyond normal business lifecycles, and suppliers must commit to maintaining data availability throughout these extended periods.

Migration Rights: Organizations must retain the right to migrate data from supplier systems without restriction or penalty. This includes both planned migrations during contract transitions and emergency migrations necessitated by supplier business failures or service discontinuations. Suppliers must provide data in standard formats and support migration activities.

Regulatory Access: Suppliers must support regulatory inspector access to data and systems as required by pharmaceutical companies. This cannot be subject to additional fees or require advance notice that could delay regulatory compliance. Suppliers must understand their role in regulatory inspections and commit to providing necessary support.

Change Control and Communication

The dynamic nature of cloud services and SaaS platforms creates unique challenges for change control that Section 7 addresses through requirements for proactive communication and impact assessment. Traditional change control models based on formal change requests and approval cycles are incompatible with continuous deployment models used by many digital service providers.

Change Notification: Suppliers must provide advance notification of changes that could affect GMP compliance or system functionality. This includes not only direct application changes but also infrastructure modifications, security updates, and business process changes. The notification period must be sufficient to allow impact assessment and implementation of any necessary mitigating measures.

Impact Assessment: Pharmaceutical companies must evaluate the GMP implications of supplier changes even when the technical impact appears minimal. A cloud provider’s infrastructure upgrade could affect system performance during critical manufacturing operations. A SaaS platform’s user interface change could impact operator training and qualification requirements. Organizations must develop change evaluation procedures that account for these indirect effects.

Emergency Changes: Suppliers must have procedures for emergency changes that balance urgent technical needs with GMP requirements. Security patches and critical bug fixes cannot wait for formal change approval cycles, but pharmaceutical companies must be notified and given opportunity to assess implications. Emergency change procedures must include retroactive impact assessment and documentation requirements.

Testing and Validation: Changes to supplier systems may require re-testing or revalidation of pharmaceutical company applications and processes. Contracts must specify supplier support for customer testing activities and establish responsibilities for validation of changes. This is particularly challenging for multi-tenant SaaS platforms where changes affect all customers simultaneously.

Rollback Capabilities: Suppliers must maintain capabilities to reverse changes that adversely affect GMP compliance or system functionality. This includes technical rollback capabilities and procedural commitments to restore service levels if changes cause operational problems. Rollback procedures must account for data integrity implications and ensure no GMP data is lost or corrupted during restoration activities.

Incident Management and Response

Section 7’s requirements for incident reporting and response acknowledge that service disruptions, security incidents, and system failures have different implications in GMP environments compared to general business applications. Suppliers must understand these implications and adapt their incident response procedures accordingly.

Incident Classification: Suppliers must classify incidents based on GMP impact rather than purely technical severity. A brief database connectivity issue might be low priority from a technical perspective but could affect batch release decisions and require immediate escalation. Suppliers must understand pharmaceutical business processes well enough to assess GMP implications accurately.

Notification Procedures: Incident notification procedures must account for pharmaceutical industry operational patterns and regulatory requirements. Manufacturing operations may run around the clock, requiring immediate notification for GMP-critical incidents. Regulatory reporting obligations may require incident documentation within specific timeframes that differ from standard business practices.

Investigation Support: Suppliers must support pharmaceutical company investigations of incidents that could affect product quality or data integrity. This includes providing detailed technical information, preserving evidence, and making subject matter experts available for investigation activities. Investigation support cannot be subject to additional fees or require formal legal processes.

Corrective Actions: Incident response must include identification and implementation of corrective actions to prevent recurrence. Suppliers must commit to addressing root causes rather than simply restoring service functionality. Corrective action plans must be documented and tracked to completion with pharmaceutical company oversight.

Regulatory Reporting: Suppliers must understand when incidents may require regulatory reporting and provide information needed to support pharmaceutical company reporting obligations. This includes detailed incident timelines, impact assessments, and corrective action documentation. Suppliers must maintain incident records for periods consistent with pharmaceutical industry retention requirements.

Performance Monitoring and Metrics

The oversight requirements in Section 7 necessitate comprehensive performance monitoring systems that go beyond traditional IT service management to encompass GMP-specific requirements and quality metrics. Organizations must implement monitoring frameworks that provide real-time visibility into supplier performance while demonstrating ongoing compliance with regulatory requirements.

GMP-Relevant Metrics: Performance monitoring must include metrics that reflect GMP impact rather than purely technical performance. System availability during manufacturing campaigns is more important than general uptime statistics. Data backup completion rates are more critical than storage utilization metrics. Response times for GMP-critical incidents require different measurement than general support ticket resolution.

Real-Time Monitoring: The dynamic nature of cloud services requires real-time monitoring capabilities rather than periodic reporting. Organizations must implement dashboard systems that provide immediate visibility into supplier performance and alert capabilities for GMP-critical events. This often requires integration between supplier monitoring systems and internal quality management platforms.

Trend Analysis: Performance monitoring must include trend analysis capabilities to identify degrading performance before it affects GMP operations. Gradual increases in system response times could indicate capacity constraints that might affect manufacturing efficiency. Increasing incident frequencies could suggest infrastructure problems that require proactive intervention.

Compliance Metrics: Monitoring systems must track compliance-related metrics such as audit trail completeness, user access control effectiveness, and change control adherence. These metrics require deeper integration with supplier systems and may not be available through standard monitoring interfaces. Organizations may need to negotiate specific compliance reporting capabilities into their service agreements.

Exception Reporting: Performance monitoring must include exception reporting capabilities that identify situations requiring management attention. Missed SLA targets, compliance deviations, and unusual system behavior must trigger immediate notifications and investigation procedures. Exception reporting thresholds must account for GMP operational requirements rather than general business practices.

Audit Trail and Documentation Integration

Section 7’s documentation requirements extend beyond static documents to encompass dynamic audit trail information and real-time system monitoring data that must be integrated with internal quality management systems. This creates significant technical and procedural challenges for organizations managing multiple supplier relationships.

Audit Trail Aggregation: Organizations using multiple suppliers must aggregate audit trail information from various sources to maintain complete records of GMP activities. A manufacturing batch might involve data from cloud-based LIMS systems, SaaS quality management platforms, and locally managed manufacturing execution systems. All audit trail information must be correlated and preserved to support regulatory requirements.

Data Format Standardization: Different suppliers provide audit trail information in different formats and structures, making aggregation and analysis challenging. Organizations must work with suppliers to establish standardized data formats or implement translation capabilities to ensure audit trail information can be effectively integrated and analyzed.

Retention Coordination: Audit trail retention requirements may exceed supplier standard practices, requiring coordination to ensure information remains available throughout required retention periods. Organizations must verify that supplier retention policies align with GMP requirements and establish procedures for retrieving historical audit trail data when needed.

Search and Retrieval: Integrated audit trail systems must provide search and retrieval capabilities that span multiple supplier systems. Regulatory investigations may require analysis of activities across multiple platforms and timeframes. Organizations must implement search capabilities that can effectively query distributed audit trail information.

Access Control Integration: Audit trail access must be controlled through integrated access management systems that span multiple suppliers. Users should not require separate authentication for each supplier system, but access controls must maintain appropriate segregation and monitoring capabilities. This often requires federated identity management systems and single sign-on capabilities.

Validation Strategies for Supplier-Managed Systems

Section 7’s responsibility requirements mean that pharmaceutical companies cannot rely solely on supplier validation activities but must implement validation strategies that encompass supplier-managed systems while avoiding duplication of effort. This requires sophisticated approaches that leverage supplier capabilities while maintaining regulatory accountability.

Hybrid Validation Models: Organizations must develop validation approaches that combine supplier-provided validation evidence with customer-specific testing and verification activities. Suppliers may provide infrastructure qualification documentation, but customers must verify that applications perform correctly on that infrastructure. SaaS providers may offer functional testing evidence, but customers must verify that functionality meets their specific GMP requirements.

Continuous Validation: The dynamic nature of supplier-managed systems requires continuous validation approaches rather than periodic revalidation cycles. Automated testing systems must verify that system functionality remains intact after supplier changes. Monitoring systems must detect performance degradation that could affect validation status. Change control procedures must include validation impact assessment for all supplier modifications.

Risk-Based Testing: Validation testing must focus on GMP-critical functionality rather than comprehensive system testing. Organizations must identify the specific functions that affect product quality and data integrity and concentrate validation efforts on these areas. This requires detailed understanding of business processes and system functionality to determine appropriate testing scope.

Supplier Validation Leverage: Organizations should leverage supplier validation activities where possible while maintaining ultimate responsibility for validation adequacy. This requires assessment of supplier validation procedures, review of testing evidence, and verification that supplier validation scope covers customer GMP requirements. Supplier validation documentation becomes input to customer validation activities rather than replacement for them.

Documentation Integration: Validation documentation must integrate supplier-provided evidence with customer-generated testing results and assessments. The final validation package must demonstrate comprehensive coverage of GMP requirements while clearly delineating supplier and customer contributions to validation activities.

Effective implementation of Section 7 requirements necessitates significant organizational changes that extend beyond traditional supplier management functions to encompass quality assurance, information technology, regulatory affairs, and legal departments. Organizations must develop cross-functional capabilities and governance structures that can manage complex supplier relationships while maintaining regulatory compliance.

Organizational Structure: Many pharmaceutical companies will need to establish dedicated supplier management functions with specific responsibility for GMP-critical supplier relationships. These functions must combine procurement expertise with quality assurance knowledge and technical understanding of computerized systems. Traditional procurement organizations typically lack the regulatory knowledge needed to manage GMP suppliers effectively.

Cross-Functional Teams: Supplier management requires coordination between multiple organizational functions including quality assurance, information technology, regulatory affairs, legal, and procurement. Cross-functional teams must be established to manage complex supplier relationships and ensure all relevant perspectives are considered in supplier selection, contract negotiation, and ongoing oversight activities.

Competency Development: Organizations must develop internal competencies in areas such as cloud infrastructure assessment, SaaS platform evaluation, and contract negotiation for digital services. Many pharmaceutical companies have limited experience in these areas and will need to invest in training and potentially external expertise to build necessary capabilities.

Technology Infrastructure: Effective supplier oversight requires significant technology infrastructure including monitoring systems, audit trail aggregation platforms, and integration capabilities. Organizations must invest in systems that can provide real-time visibility into supplier performance and integrate supplier-provided information with internal quality management systems.

Process Standardization: Supplier management processes must be standardized across the organization to ensure consistent approaches and facilitate knowledge sharing. This includes risk assessment methodologies, audit procedures, contract templates, and performance monitoring frameworks. Standardization becomes particularly important as organizations manage increasing numbers of supplier relationships.

Regulatory Implications and Inspection Readiness

Section 7 requirements significantly change regulatory inspection dynamics by extending inspector access and scrutiny to supplier systems and processes. Organizations must prepare for inspections that encompass their entire supply chain rather than just internal operations, while ensuring suppliers understand and support regulatory compliance obligations.

Extended Inspection Scope: Regulatory inspectors may request access to supplier systems, documentation, and personnel as part of pharmaceutical company inspections. This extends inspection scope beyond traditional facility boundaries to encompass cloud data centers, SaaS platform operations, and supplier quality management systems. Organizations must ensure suppliers understand these obligations and commit to providing necessary support.

Supplier Participation: Suppliers may be required to participate directly in regulatory inspections through system demonstrations, expert testimony, or document provision. This represents a significant change from traditional inspection models where suppliers remained in the background. Suppliers must understand regulatory expectations and prepare to engage directly with inspectors when required.

Documentation Coordination: Inspection preparation must coordinate documentation from multiple suppliers and ensure consistent presentation of integrated systems and processes. This requires significant advance planning and coordination with suppliers to ensure required documentation is available and personnel can explain supplier-managed systems effectively.

Response Coordination: Inspection responses and corrective actions may require coordination with multiple suppliers, particularly when findings relate to integrated systems or shared responsibilities. Organizations must establish procedures for coordinating supplier responses and ensuring corrective actions address root causes across the entire supply chain.

Ongoing Readiness: Inspection readiness becomes a continuous requirement rather than periodic preparation as supplier-managed systems undergo constant change. Organizations must maintain ongoing documentation updates, supplier coordination, and internal knowledge to ensure they can explain and defend their supplier management practices at any time.

Implementation Roadmap and Timeline

Organizations implementing Section 7 requirements must develop comprehensive implementation roadmaps that account for the complexity of modern supplier relationships and the time required to establish new capabilities and procedures. Implementation planning must balance regulatory compliance timelines with practical constraints of supplier negotiation and system modification.

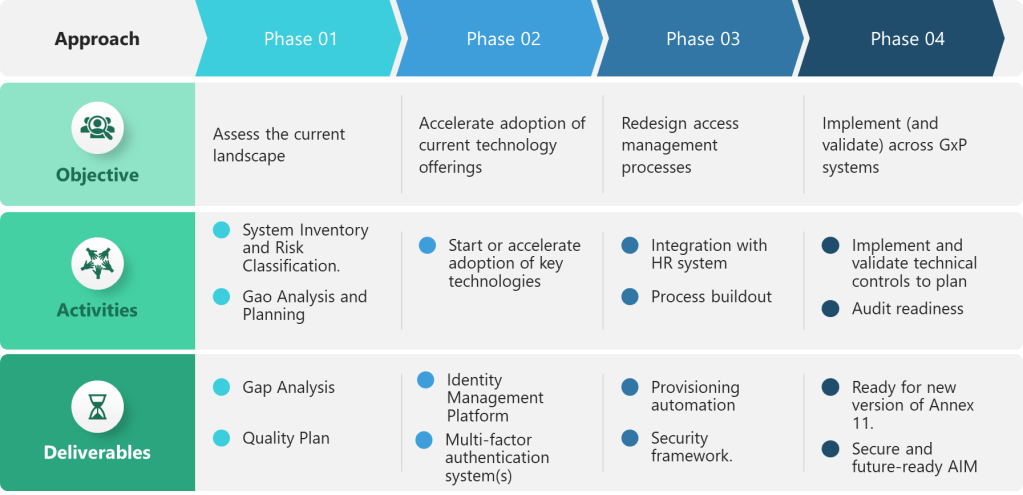

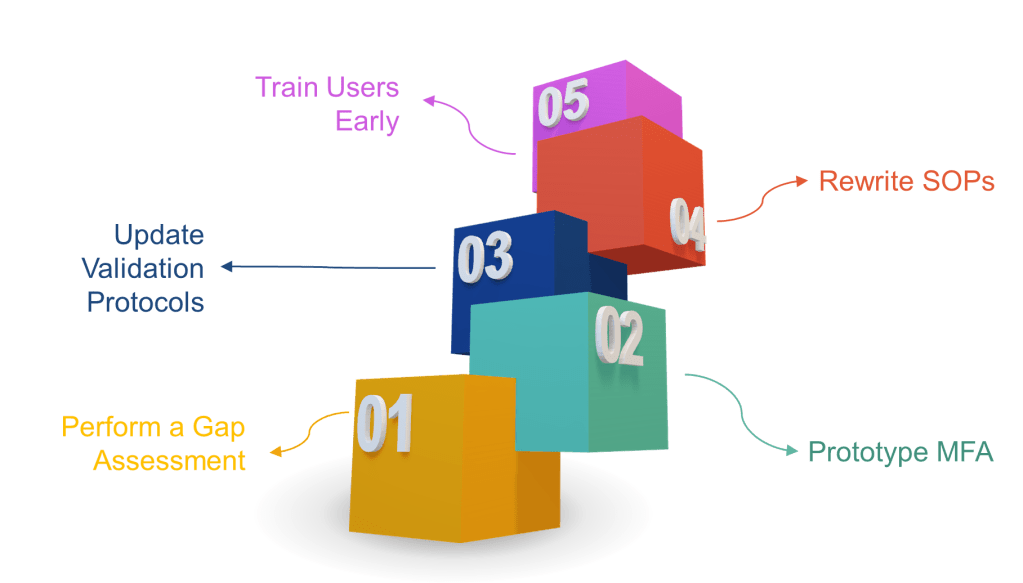

Assessment Phase (Months 1-6): Organizations must begin with comprehensive assessment of current supplier relationships, system dependencies, and gap identification. This includes inventory of all suppliers supporting GMP activities, risk classification of supplier relationships, and evaluation of current contracts and procedures against Section 7 requirements. Assessment activities should identify high-priority gaps requiring immediate attention and longer-term improvements needed for full compliance.

Supplier Engagement (Months 3-12): Parallel to internal assessment, organizations must engage suppliers to communicate new requirements and negotiate contract modifications. This process varies significantly based on supplier type and relationship maturity. Hyperscale cloud providers typically resist contract modifications but may offer additional compliance documentation or services. Specialized pharmaceutical software vendors may be more willing to accommodate specific requirements but may require time to develop new capabilities.

Contract Renegotiation (Months 6-18): Contract modifications to incorporate Section 7 requirements represent major undertakings that may require extensive negotiation and legal review. Organizations should prioritize critical suppliers and high-risk relationships while developing template approaches that can be applied more broadly. Contract renegotiation timelines must account for supplier response times and potential resistance to pharmaceutical-specific requirements.

Procedure Development (Months 6-12): New procedures must be developed for supplier oversight, performance monitoring, audit planning, and incident response. These procedures must integrate with existing quality management systems while accommodating the unique characteristics of different supplier types. Procedure development should include training materials and competency assessment approaches to ensure effective implementation.

Technology Implementation (Months 9-24): Monitoring systems, audit trail aggregation platforms, and integration capabilities require significant technology implementation efforts. Organizations should plan for extended implementation timelines and potential integration challenges with supplier systems. Technology implementation should be phased to address critical suppliers first while building capabilities for broader deployment.

Training and Competency (Months 12-18): Personnel across multiple functions require training on new supplier management approaches and specific competencies for managing different types of supplier relationships. Training programs must be developed for various roles including supplier managers, quality assurance personnel, auditors, and technical specialists. Competency assessment and ongoing training requirements must be established to maintain capabilities as supplier relationships evolve.

Ongoing Monitoring (Continuous): Full implementation of Section 7 requirements establishes ongoing monitoring and continuous improvement processes that become permanent organizational capabilities. Performance monitoring, supplier relationship management, and compliance assessment become routine activities that require sustained resource allocation and management attention.

Future Implications and Industry Evolution

Section 7 represents more than regulatory compliance requirements—it establishes a framework for pharmaceutical industry evolution toward fully integrated digital supply chains where traditional boundaries between internal and external operations become increasingly meaningless. Organizations that successfully implement these requirements will gain competitive advantages through enhanced operational flexibility and risk management capabilities.

Supply Chain Integration: Section 7 requirements drive deeper integration between pharmaceutical companies and their suppliers, creating opportunities for improved efficiency and innovation. Real-time performance monitoring enables proactive management of supply chain risks. Integrated documentation and audit trail systems provide comprehensive visibility into end-to-end processes. Enhanced communication and change management procedures facilitate faster implementation of improvements and innovations.

Technology Evolution: Regulatory requirements for supplier oversight will drive technology innovation in areas such as automated monitoring systems, audit trail aggregation platforms, and integrated validation frameworks. Suppliers will develop pharmaceutical-specific capabilities to meet customer requirements and differentiate their offerings. Technology vendors will emerge to provide specialized solutions for managing complex supplier relationships in regulated industries.

Industry Standards: Section 7 requirements will likely drive development of industry standards for supplier management, contract templates, and integration approaches. Trade associations and standards organizations will develop best practice guidance and template documents to support implementation. Convergence around common approaches will reduce implementation costs and improve interoperability between suppliers and customers.

Regulatory Harmonization: The risk-based, lifecycle-oriented approach embodied in Section 7 aligns with regulatory trends in other jurisdictions and may drive harmonization of global supplier management requirements. FDA Computer Software Assurance guidance shares similar risk-based philosophies, and other regulatory authorities are likely to adopt comparable approaches. Harmonization reduces compliance burden for global pharmaceutical companies and suppliers serving multiple markets.

Competitive Differentiation: Organizations that excel at supplier management under Section 7 requirements will gain competitive advantages through reduced risk, improved operational efficiency, and enhanced innovation capabilities. Effective supplier partnerships enable faster implementation of new technologies and more agile responses to market opportunities. Strong supplier relationships provide resilience during disruptions and enable rapid scaling of operations.

Conclusion: The Strategic Imperative

Section 7 of the draft Annex 11 represents the most significant change in pharmaceutical supplier management requirements since the introduction of 21CFRPart11. The transformation from perfunctory oversight to comprehensive management reflects the reality that modern pharmaceutical operations depend fundamentally on external providers for capabilities that directly affect product quality and patient safety.

Organizations that approach Section 7 implementation as mere regulatory compliance will miss the strategic opportunity these requirements represent. The enhanced supplier management capabilities required by Section 7 enable pharmaceutical companies to leverage external innovation more effectively, manage operational risks more comprehensively, and respond to market opportunities more rapidly than traditional approaches allow.

However, successful implementation requires sustained commitment and significant investment in organizational capabilities, technology infrastructure, and relationship management. Organizations cannot simply modify existing procedures—they must fundamentally reconceptualize their approach to supplier relationships and develop entirely new competencies for managing digital supply chains.

The implementation timeline for Section 7 requirements extends well beyond the expected 2026 effective date for the final Annex 11. Organizations that begin implementation now will have competitive advantages through enhanced capabilities and supplier relationships. Those that delay implementation will find themselves struggling to achieve compliance while their competitors demonstrate regulatory leadership through proactive adoption.

Section 7 acknowledges that pharmaceutical manufacturing has evolved from discrete operations conducted within company facilities to integrated processes that span multiple organizations and geographic locations. Regulatory compliance must evolve correspondingly to encompass these extended operations while maintaining the rigor and accountability that ensures product quality and patient safety.

The future of pharmaceutical manufacturing belongs to organizations that can effectively manage complex supplier relationships while maintaining regulatory compliance and operational excellence. Section 7 provides the framework for this evolution—organizations that embrace it will thrive, while those that resist it will find themselves increasingly disadvantaged in a digitized, interconnected industry.

The message of Section 7 is clear: supplier management is no longer a support function but a core competency that determines organizational success in the modern pharmaceutical industry. Organizations that recognize this reality and invest accordingly will build sustainable competitive advantages that extend far beyond regulatory compliance to encompass operational excellence, innovation capability, and strategic flexibility.

The transformation required by Section 7 is comprehensive and challenging, but it positions the pharmaceutical industry for a future where effective supplier partnerships enable better medicines, safer products, and more efficient operations. Organizations that master these requirements will lead industry evolution toward more innovative, efficient, and patient-focused pharmaceutical development and manufacturing.

| Requirement Area | Current Annex 11 (2011) | Draft Annex 11 Section 7 (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Supplier Management | Third parties (suppliers, service providers) for systems/services | All vendors, service providers, internal IT departments for GMP systems |

| MAH/Manufacturer Responsibility | Basic – formal agreements must exist | Regulated user remains fully responsible regardless of outsourcing |

| Risk-Based Assessment | Audit need based on risk assessment | Audit/assessment required according to risk and system criticality |

| Supplier Qualification Process | Competence and reliability key factors | Detailed qualification with thorough assessment of procedures/documentation |

| Written Agreements/Contracts | Formal agreements with clear responsibilities | Comprehensive contracts with specific GMP responsibilities defined |

| Audit Requirements | Risk-based audit decisions | Risk-based audits with defined conditions and support requirements |

| Ongoing Oversight | Not explicitly detailed | Effective oversight via SLAs and KPIs with defined reporting |

| Change Management | Not specified | Proactive change notification and assessment requirements |

| Data Ownership & Access | Not explicitly addressed | Clear data ownership, backup, retention responsibilities in contracts |

| Documentation Availability | Documentation should be available to inspectors | All required documentation must be accessible and explainable |

| Service Level Agreements | Not mentioned | Mandatory SLAs with KPIs, reporting, and oversight mechanisms |

| Incident Management | Not specified | Incident reporting, answer times, resolution procedures required |

| Cloud Service Providers | Not specifically addressed | Explicitly included with comprehensive management requirements |

| SaaS Platform Management | Not mentioned | Full coverage including multi-tenant platforms and cloud services |

| Subcontractor Control | Not explicitly covered | Complete visibility and control over all subcontracting arrangements |

| Performance Monitoring | Not specified | Continuous monitoring with documented KPIs and performance metrics |

| Requalification | Not mentioned | Regular, risk-based requalification processes required |

| Termination/Exit Strategy | Not addressed | Exit strategies and data migration procedures must be defined |