Ready or not, the EU’s draft revision of Annex 11 is moving toward finalization, and its brand-new Section 13 on electronic signatures is a wake-up call for anyone still treating digital authentication as just Part 11 with an accent. In this post I will take a deep dive into what’s changing, why it matters, and how to keep your quality system out of the regulatory splash zone.

Section 13 turns electronic signatures from a check-the-box formality into a risk-based, security-anchored discipline. Think multi-factor authentication, time-zone stamps, hybrid wet-ink safeguards, and explicit “non-repudiation” language—all enforced at the same rigor as system login. If your current SOPs still assume username + password = done, it’s time to start planning some improvements.

Why the Rewrite?

- Tech has moved on: Biometric ID, cloud PaaS, and federated identity management were sci-fi when the 2011 Annex 11 dropped.

- Threat landscape: Ransomware and credential stuffing didn’t exist at today’s scale. Regulators finally noticed.

- Global convergence: The FDA’s Computer Software Assurance (CSA) draft and PIC/S data-integrity guides pushed the EU to level up.

For the bigger regulatory context, see my post on EMA GMP Plans for Regulation Updates.

What’s Actually New in Section 13?

| Topic | 2011 Annex 11 | Draft Annex 11 (2025) | 21 CFR Part 11 | Why You Should Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentication at Signature | Silent | Must equal or exceed login strength; first sign = full re-auth, subsequent signs = pwd/biometric; smart-card-only = banned | Two identification components | Forces MFA or biometrics; goodbye “remember me” shortcuts |

| Time & Time-Zone | Date + time (manual OK) | Auto-captured and time-zone logged | Date + time (no TZ) | Multisite ops finally get defensible chronology |

| Signature Meaning Prompt | Not required | System must ask user for purpose (approve, review…) | Required but less prescriptive | Eliminates “mystery clicks” that auditors love to exploit |

| Manifestation Elements | Minimal | Full name, username, role, meaning, date/time/TZ | Name, date, meaning | Closes attribution gaps; boosts ALCOA+ “Legible” |

| Indisputability Clause | “Same impact” | Explicit non-repudiation mandate | Equivalent legal weight | Sets the stage for eIDAS/federated ID harmonization |

| Record Linking After Change | Permanent link | If record altered post-sign, signature becomes void/flagged | Link cannot be excised | Ends stealth edits after approval |

| Hybrid Wet-Ink Control | Silent | Hash code or similar to break link if record changes | Silent | Lets you keep occasional paper without tanking data integrity |

| Open Systems / Trusted Services | Silent | Must comply with “national/international trusted services” (read: eIDAS) | Extra controls, but legacy wording | Validates cloud signing platforms out of the box |

The Implications

Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) Is Now Table Stakes

Because the draft explicitly bars any authentication method that relies solely on a smart card or a static PIN, every electronic signature now has to be confirmed with an additional, independent factor—such as a password, biometric scan, or time-limited one-time code—so that the credential used to apply the signature is demonstrably different from the one that granted the user access to the system in the first place.

Time-Zone Logging Kills Spreadsheet Workarounds

One of the more subtle but critical updates in Draft Annex 11’s Section 13.4 is the explicit requirement for automatic logging of the time zone when electronic signatures are applied. Unlike previous guidance—whether under the 2011 Annex 11 or 21 CFR Part 11—that only mandated the capture of date and time (often allowing manual entry or local system time), the draft stipulates that systems must automatically capture the precise time and associated time zone for each signature event. This seemingly small detail has monumental implications for data integrity, traceability, and regulatory compliance. Why does this matter? For global pharmaceutical operations spanning multiple time zones, manual or local-only timestamps often create ambiguous or conflicting audit trails, leading to discrepancies in event sequencing. Companies relying on spreadsheets or legacy systems that do not incorporate time zone information effectively invite errors where a signature in one location appears to precede an earlier event simply due to zone differences. This ambiguity can undermine the “Contemporaneous” and “Enduring” principles of ALCOA+, principles the draft Annex 11 explicitly reinforces throughout electronic signature requirements. By mandating automated, time zone-aware timestamping, Draft Annex 11 Section 13.4 ensures that electronic signature records maintain a defensible and standardized chronology across geographies, eliminating the need for cumbersome manual reconciliation or retrospective spreadsheet corrections. This move not only tightens compliance but also supports modern, centralized data review and analytics where uniform timestamping is essential. If your current systems or SOPs rely on manual date/time entry or overlook time zone logging, prepare for significant system and procedural updates to meet this enhanced expectation once the draft Annex 11 is finalized. .

Hybrid Records Are Finally Codified

If you still print a batch record for wet-ink QA approval, Section 13.9 lets you keep the ritual—but only if a cryptographic hash or similar breaks when someone tweaks the underlying PDF. Expect a flurry of DocuSign-scanner-hash utilities.

Open-System Signatures Shift Liability

Draft Annex 11’s Section 13.2 represents perhaps the most strategically significant change in electronic signature liability allocation since 21 CFR Part 11 was published in 1997. The provision states that “Where the system owner does not have full control of system accesses (open systems), or where required by other legislation, electronic signatures should, in addition, meet applicable national and international requirements, such as trusted services”. This seemingly simple sentence fundamentally reshapes liability relationships in modern pharmaceutical IT architectures.

Defining the Open System Boundary

The draft Annex 11 adopts the 21 CFR Part 11 definition of open systems—environments where system owners lack complete control over access and extends it into contemporary cloud, SaaS, and federated identity scenarios. Unlike the original Part 11 approach, which merely required “additional measures such as document encryption and use of appropriate digital signature standards”, Section 13.2 creates a positive compliance obligation by mandating adherence to “trusted services” frameworks.

This distinction is critical: while Part 11 treats open systems as inherently risky environments requiring additional controls, draft Annex 11 legitimizes open systems provided they integrate with qualified trust service providers. Organizations no longer need to avoid cloud-based signature services; instead, they must ensure those services meet eIDAS-qualified standards or equivalent national frameworks.

The Trusted Services Liability Transfer

Section 13.2’s reference to “trusted services” directly incorporates European eIDAS Regulation 910/2014 into pharmaceutical GMP compliance, creating what amounts to a liability transfer mechanism. Under eIDAS, Qualified Trust Service Providers (QTSPs) undergo rigorous third-party audits, maintain certified infrastructure, and provide legal guarantees about signature validity and non-repudiation. When pharmaceutical companies use eIDAS-qualified signature services, they effectively transfer signature validity liability from their internal systems to certified external providers.

This represents a fundamental shift from the 21 CFR Part 11 closed-system preference, where organizations maintained complete control over signature infrastructure but also bore complete liability for signature failures. Draft Annex 11 acknowledges that modern pharmaceutical operations often depend on cloud service providers, federated authentication systems, and external trust services—and provides a regulatory pathway to leverage these technologies while managing liability exposure.

Practical Implications for SaaS Platforms

The most immediate impact affects organizations using Software-as-a-Service platforms for clinical data management, quality management, or document management. Under current Annex 11 and Part 11, these systems often require complex validation exercises to demonstrate signature integrity, with pharmaceutical companies bearing full responsibility for signature validity even when using external platforms.

Section 13.2 changes this dynamic by validating reliance on qualified trust services. Organizations using platforms like DocuSign, Adobe Sign, or specialized pharmaceutical SaaS providers can now satisfy Annex 11 requirements by ensuring their chosen platforms integrate with eIDAS-qualified signature services. The pharmaceutical company’s validation responsibility shifts from proving signature technology integrity to verifying trust service provider qualifications and proper integration.

Integration with Identity and Access Management

Draft Annex 11’s Section 11 (Identity and Access Management) works in conjunction with Section 13.2 to support federated identity scenarios common in modern pharmaceutical operations. Organizations can now implement single sign-on (SSO) systems with external identity providers, provided the signature components integrate with trusted services. This enables scenarios where employees authenticate through corporate Active Directory systems but execute legally binding signatures through eIDAS-qualified providers.

The liability implications are significant: authentication failures become the responsibility of the identity provider (within contractual limits), while signature validity becomes the responsibility of the qualified trust service provider. The pharmaceutical company retains responsibility for proper system integration and user access controls, but shares technical implementation liability with certified external providers.

Cloud Service Provider Risk Allocation

For organizations using cloud-based LIMS, MES, or quality management systems, Section 13.2 provides regulatory authorization to implement signature services hosted entirely by external providers. Cloud service providers offering eIDAS-compliant signature services can contractually accept liability for signature technical implementation, cryptographic integrity, and legal validity—provided they maintain proper trust service qualifications.

This risk allocation addresses a long-standing concern in pharmaceutical cloud adoption: the challenge of validating signature infrastructure owned and operated by external parties. Under Section 13.2, organizations can rely on qualified trust service provider certifications rather than conducting detailed technical validation of cloud provider signature implementations.

Harmonization with Global Standards

Section 13.2’s “national and international requirements” language extends beyond eIDAS to encompass other qualified electronic signature frameworks. This includes Swiss ZertES standards and Canadian digital signature regulations,. Organizations operating globally can implement unified signature platforms that satisfy multiple regulatory requirements through single trusted service provider integrations.

The practical effect is regulatory arbitrage: organizations can choose signature service providers based on the most favorable combination of technical capabilities, cost, and regulatory coverage, rather than being constrained by local regulatory limitations.

Supplier Assessment Transformation

Draft Annex 11’s Section 7 (Supplier and Service Management) requires comprehensive supplier assessment for computerized systems. However, Section 13.2 creates a qualified exception for eIDAS-certified trust service providers: organizations can rely on third-party certification rather than conducting independent technical assessments of signature infrastructure.

This significantly reduces supplier assessment burden for signature services. Instead of auditing cryptographic implementations, hardware security modules, and signature validation algorithms, organizations can verify trust service provider certifications and assess integration quality. The result: faster implementation cycles and reduced validation costs for signature-enabled systems.

Audit Trail Integration Considerations

The liability shift enabled by Section 13.2 affects audit trail management requirements detailed in draft Annex 11’s expanded Section 12 (Audit Trails). When signature events are managed by external trust service providers, organizations must ensure signature-related audit events are properly integrated with internal audit trail systems while maintaining clear accountability boundaries.

Qualified trust service providers typically provide comprehensive signature audit logs, but organizations remain responsible for correlation with business process audit trails. This creates shared audit trail management where signature technical events are managed externally but business context remains internal responsibility.

Competitive Advantages of Early Adoption

Organizations that proactively implement Section 13.2 requirements gain several strategic advantages:

- Reduced Infrastructure Costs: Elimination of internal signature infrastructure maintenance and validation overhead

- Enhanced Security: Leverage specialized trust service provider security expertise and certified infrastructure

- Global Scalability: Unified signature platforms supporting multiple regulatory jurisdictions through single provider relationships

- Accelerated Digital Transformation: Faster deployment of signature-enabled processes through validated external services

- Risk Transfer: Contractual liability allocation with qualified external providers rather than complete internal risk retention

Section 13.2 transforms open system electronic signatures from compliance challenges into strategic enablers of digital pharmaceutical operations. By legitimizing reliance on qualified trust services, the draft Annex 11 enables organizations to leverage best-in-class signature technologies while managing regulatory compliance and liability exposure through proven external partnerships. The result: more secure, cost-effective, and globally scalable electronic signature implementations that support advanced digital quality management systems.

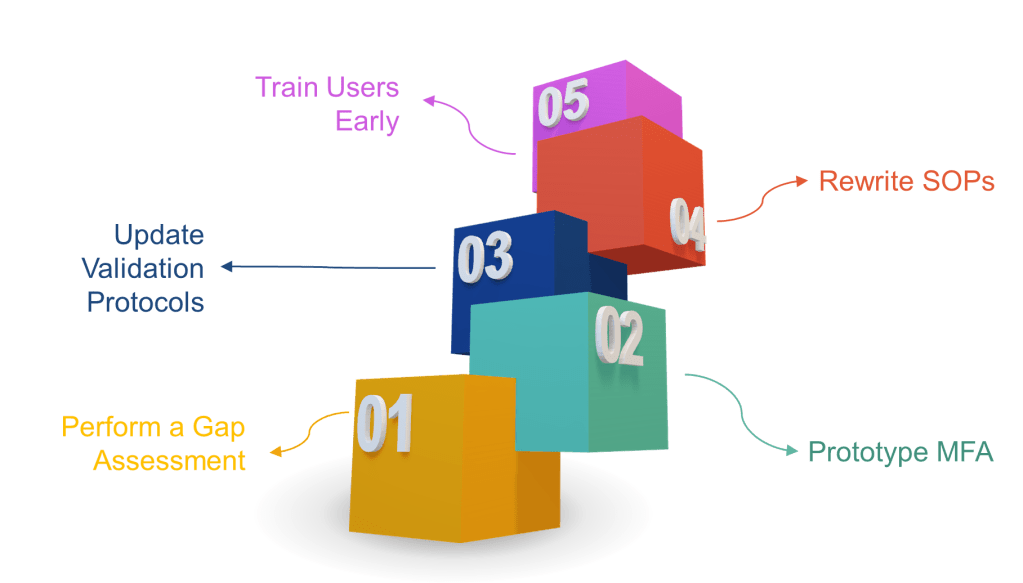

How to Get Ahead (Instead of Playing Cleanup)

- Perform a gap assessment now—map every signature point to the new rules.

- Prototype MFA in your eDMS or MES. If users scream about friction, remind them that ransomware is worse.

- Update validation protocols to include time-zone, hybrid record, and non-repudiation tests.

- Rewrite SOPs to include signature-meaning prompts and periodic access-right recertification.

- Train users early. A 30-second “why you must re-authenticate” explainer video beats 300 deviations later.

Final Thoughts

The draft Annex 11 doesn’t just tweak wording—it yanks electronic signatures into the 2020s. Treat Section 13 as both a compliance obligation and an opportunity to slash latent data-integrity risk. Those who adapt now will cruise through 2026/2027 inspections while the laggards scramble for remediation budgets.