Pharmaceutical regulatory frameworks have evolved substantially over the past two decades, moving from fixed-approval models—where products remained frozen in approved specifications after authorization—toward dynamic lifecycle management approaches that acknowledge manufacturing reality. Products don’t remain static across their commercial life. Manufacturing sites scale up. Suppliers introduce new materials. Analytical technologies improve. Equipment upgrades occur. Process understanding deepens through continued manufacturing experience. Managing these inevitable changes while maintaining product quality and regulatory compliance has historically required regulatory submission and approval for nearly every meaningful post-approval modification, regardless of risk magnitude or scientific foundation.

This traditional submission-for-approval model reflected regulatory frameworks designed when pharmaceutical manufacturing was less understood, analytical capabilities were more limited, and standardized post-approval change procedures were the best available mechanism for regulatory oversight. Organizations would develop products, conduct manufacturing validation, obtain market approval, then essentially operate within a frozen state of approval—any meaningful change required regulatory notification and frequently required prior approval before distribution of product made under the changed conditions.

The limitations of this approach became increasingly apparent over the 2000s. Regulatory approval cycles extended as the volume of submitted changes increased. Organizations deferred beneficial improvements to avoid submission burden. Supply chain disruptions couldn’t be addressed quickly because qualified alternative suppliers required prior approval supplements with multi-year review timelines. Manufacturing facilities accumulated technical debt—aging equipment, suboptimal processes, outdated analytical methods—because upgrading would trigger regulatory requirements disproportionate to the quality impact. Quality culture inadvertently incentivized resistance to change rather than continuous improvement.

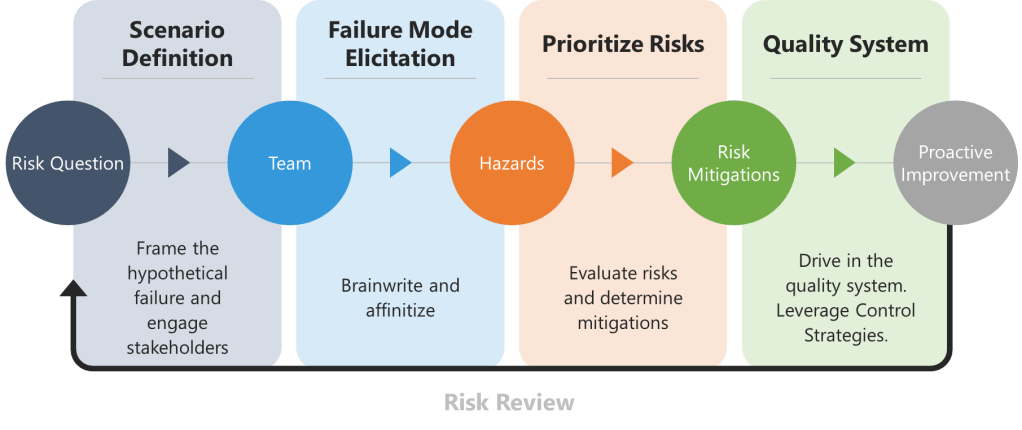

Simultaneously, the pharmaceutical industry’s scientific understanding evolved. Quality by Design (QbD) principles, implemented through ICH Q8 guidance on pharmaceutical development, enabled organizations to develop products with comprehensive process understanding and characterized design spaces. ICH Q10 on pharmaceutical quality systems introduced systematic approaches to knowledge management and continual improvement. Risk management frameworks (ICH Q9) provided scientific methods to evaluate change impact with quantitative rigor. This growing scientific sophistication created opportunity for more nuanced, risk-informed post-approval change management than the binary approval/no approval model permitted.

ICH Q12 “Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management” represents the evolution toward scientific, risk-based lifecycle management frameworks. Rather than treating all post-approval changes as equivalent regulatory events, Q12 provides a comprehensive toolbox: Established Conditions (designating which product elements warrant regulatory oversight if changed), Post-Approval Change Management Protocols (enabling prospective agreement on how anticipated changes will be implemented), categorized reporting approaches (aligning regulatory oversight intensity with quality risk), and the Product Lifecycle Management (PLCM) document as central repository for this lifecycle strategy.

The PLCM document itself represents this evolutionary mindset. Where traditional regulatory submissions distribute CMC information across dozens of sections following Common Technical Document structure, the PLCM document consolidates lifecycle management strategy into a central location accessible to regulatory assessors, inspectors, and internal quality teams. The document serves “as a central repository in the marketing authorization application for Established Conditions and reporting categories for making changes to Established Conditions”. It outlines “the specific plan for product lifecycle management that includes the Established Conditions, reporting categories for changes to Established Conditions, PACMPs (if used), and any post-approval CMC commitments”.

This approach doesn’t abandon regulatory oversight. Rather, it modernizes oversight mechanisms by aligning regulatory scrutiny with scientific understanding and risk assessment. High-risk changes warrant prior approval. Moderate-risk changes warrant notification to maintain regulators’ awareness. Low-risk changes can be managed through pharmaceutical quality systems without regulatory notification—though the robust quality system remains subject to regulatory inspection.

The shift from fixed-approval to lifecycle management represents maturation in how the pharmaceutical industry approaches quality. Instead of assuming that quality emerges from regulatory permission, the evolved approach recognizes that quality emerges from robust understanding, effective control systems, and systematic continuous improvement. Regulatory frameworks support this quality assurance by maintaining oversight appropriate to risk, enabling efficient improvement implementation, and incentivizing investment in product and process understanding that justifies flexibility.

For pharmaceutical organizations, this evolution creates both opportunity and complexity. The opportunity is substantial: post-approval flexibility enabling faster response to supply chain challenges, incentives for continuous improvement no longer penalized by submission burden, manufacturing innovation supported by risk-based change management rather than constrained by regulatory caution. The complexity emerges from requirements to build the organizational capability, scientific understanding, and quality system infrastructure supporting this more sophisticated approach.

The PLCM document is the central planning and communication tool, making this evolution operational. Understanding what PLCM documents are, how they’re constructed, and how they connect control strategy development to commercial lifecycle management is essential for organizations navigating this transition from fixed-approval models toward dynamic, evidence-based lifecycle management.

Established Conditions: The Foundation Underlying PLCM Documents

The PLCM document cannot be understood without first understanding Established Conditions—the regulatory construct that forms the foundation for modern lifecycle management approaches. Established Conditions (ECs) are elements in a marketing application considered necessary to assure product quality and therefore requiring regulatory submission if changed post-approval. This definition appears straightforward until you confront the judgment required to distinguish “necessary to assure product quality” from the extensive supporting information submitted in regulatory applications that doesn’t meet this threshold.

The pharmaceutical development process generates enormous volumes of data. Formulation screening studies. Process characterization experiments. Analytical method development. Stability studies. Scale-up campaigns. Manufacturing experience from clinical trial material production. Much of this information appears in regulatory submissions because it supports and justifies the proposed commercial manufacturing process and control strategy. But not all submitted information constitutes an Established Condition.

Consider a monoclonal antibody purification process submitted in a biologics license application. The application describes the chromatography sequence: Protein A capture, viral inactivation, anion exchange polish, cation exchange polish. For each step, the application provides:

- Column resin identity and supplier

- Column dimensions and bed height

- Load volume and load density

- Buffer compositions and pH

- Flow rates

- Gradient profiles

- Pool collection criteria

- Development studies showing how these parameters were selected

- Process characterization data demonstrating parameter ranges that maintain product quality

- Viral clearance validation demonstrating step effectiveness

Which elements are Established Conditions requiring regulatory submission if changed? Which are supportive information that can be managed through the Pharmaceutical Quality System without regulatory notification?

The traditional regulatory approach made everything potentially an EC through conservative interpretation—any element described in the application might require submission if changed. This created perverse incentives against thorough process description (more detail creates more constraints) and against continuous improvement (changes trigger submission burden regardless of quality impact). ICH Q12 explicitly addresses this problem by distinguishing ECs from supportive information and providing frameworks for identifying ECs based on product and process understanding, quality risk management, and control strategy design.

The guideline describes three approaches to identifying process parameters as ECs:

Minimal parameter-based approach: Critical process parameters (CPPs) and other parameters where impact on product quality cannot be reasonably excluded are identified as ECs. This represents the default position requiring limited process understanding—if you haven’t demonstrated that a parameter doesn’t impact quality, assume it’s critical and designate it an EC. For our chromatography example, this approach would designate most process parameters as ECs: resin type, column dimensions, load parameters, buffer compositions, flow rates, gradient profiles. Only clearly non-impactful variables (e.g., specific pump model, tubing lengths within reasonable ranges) would be excluded.

Enhanced parameter-based approach: Leveraging extensive process characterization and understanding of parameter impacts on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), the organization identifies which parameters are truly critical versus those demonstrated to have minimal quality impact across realistic operational ranges. Process characterization studies using Design of Experiments (DoE), prior knowledge from similar products, and mechanistic understanding support justifications that certain parameters, while described in the application for completeness, need not be ECs because quality impact has been demonstrated to be negligible. For our chromatography process, enhanced understanding might demonstrate that precise column dimensions matter less than maintaining appropriate bed height and superficial velocity within characterized ranges. Gradient slope variations within defined design space don’t impact product quality measurably. Flow rate variations of ±20% from nominal don’t affect separation performance meaningfully when other parameters compensate appropriately.

Performance-based approach: Rather than designating input parameters (process settings) as ECs, this approach designates output performance criteria—in-process or release specifications that assure quality regardless of how specific parameters vary. For chromatography, this might mean the EC is aggregate purity specification rather than specific column operating parameters. As long as the purification process delivers aggregates below specification limits, variation in how that outcome is achieved doesn’t require regulatory notification. This provides maximum flexibility but requires robust process understanding, appropriate performance specifications representing quality assurance, and effective pharmaceutical quality system controls.

The choice among these approaches depends on product and process understanding available at approval and organizational lifecycle management strategy. Products developed with minimal Quality by Design (QbD) application, limited process characterization, and traditional “recipe-based” approaches default toward minimal parameter-based EC identification—describing most elements as ECs because insufficient knowledge exists to justify alternatives. Products developed with extensive QbD, comprehensive process characterization, and demonstrated design spaces can justify enhanced or performance-based approaches that provide greater post-approval flexibility.

This creates strategic implications. Organizations implementing ICH Q12 for legacy products often confront applications describing processes in detail without the underlying characterization studies that would support enhanced EC approaches. The submitted information implies everything might be critical because nothing was systematically demonstrated non-critical. Retrofitting ICH Q12 concepts requires either accepting conservative EC designation (reducing post-approval flexibility) or conducting characterization studies to generate understanding supporting more nuanced EC identification. The latter option represents significant investment but potentially generates long-term value through reduced regulatory submission burden for routine lifecycle changes.

For new products, the strategic decision occurs during pharmaceutical development. QbD implementation, process characterization investment, and design space establishment aren’t simply about demonstrating understanding to reviewers—they create the foundation for efficient lifecycle management by enabling justified EC identification that balances quality assurance with operational flexibility.

The PLCM Document Structure: Central Repository for Lifecycle Strategy

The PLCM document consolidates this EC identification and associated lifecycle management planning into a central location within the regulatory application. ICH Q12 describes the PLCM document as serving “as a central repository in the marketing authorization application for ECs and reporting categories for making changes to ECs”. The document “outlines the specific plan for product lifecycle management that includes the ECs, reporting categories for changes to ECs, PACMPs (if used) and any post-approval CMC commitments”.

The functional purpose is transparency and predictability. Regulatory assessors reviewing a marketing application can locate the PLCM document and immediately understand:

- Which elements the applicant considers Established Conditions (versus supportive information)

- The reporting category the applicant believes appropriate if each EC changes (prior approval, notification, or managed solely in PQS)

- Any Post-Approval Change Management Protocols (PACMPs) proposed for planned future changes

- Specific post-approval CMC commitments made during regulatory negotiations

This consolidation addresses a persistent challenge in regulatory assessment and inspection. Traditional applications distribute CMC information across dozens of sections following Common Technical Document (CTD) structure. Critical process parameters appear in section 3.2.S.2.2 or 3.2.P.3.3. Specifications appear in 3.2.S.4.1 or 3.2.P.5.1. Analytical procedures scatter across multiple sections. Control strategy discussions appear in pharmaceutical development sections. Regulatory commitments might exist in scattered communications, meeting minutes, and approval letters accumulated over the years.

When post-approval changes arise, determining what requires submission involves archeology through historical submissions, approval letters, and regional regulatory guidance. Different regional regulatory authorities might interpret submission requirements differently. Change control groups debate whether manufacturing site changes to mixing speed from 150 RPM to 180 RPM triggers prior approval (if RPM was specified in the approved application) or represent routine optimization (if only “appropriate mixing” was specified).

The PLCM document centralizes this information and makes commitments explicit. When properly constructed and maintained, the PLCM becomes the primary reference for change management decisions and regulatory inspection discussions about lifecycle management approach.

Core Elements of the PLCM Document

ICH Q12 specifies that the PLCM document should contain several key elements:

Summary of product control strategy: A high-level summary clarifying and highlighting which control strategy elements should be considered ECs versus supportive information. This summary addresses the fundamental challenge that control strategies contain extensive elements—material controls, in-process testing, process parameter monitoring, release testing, environmental monitoring, equipment qualification requirements, cleaning validation—but not all control strategy elements necessarily rise to EC status requiring regulatory submission if changed. The control strategy summary in the PLCM document maps this landscape, distinguishing legally binding commitments from quality system controls.

Established Conditions listing: The proposed ECs for the product should be listed comprehensively with references to detailed information located elsewhere in the CTD/eCTD structure. A tabular format is recommended though not mandatory. The table typically includes columns for: CTD section reference, EC description, justification for EC designation, current approved state, and reporting category for changes.

Reporting category assignments: For each EC, the reporting category indicates whether changes require prior approval (major changes with high quality risk), notification to regulatory authority (moderate changes with manageable risk), or can be managed solely within the PQS without regulatory notification (minimal or no quality risk). These categorizations should align with regional regulatory frameworks (21 CFR 314.70 in the US, EU variation regulations, equivalent frameworks in other ICH regions) while potentially proposing justified deviations based on product-specific risk assessment.

Post-Approval Change Management Protocols: If the applicant has developed PACMPs for anticipated future changes, these should be referenced in the PLCM document with location of the detailed protocols elsewhere in the submission. PACMPs represent prospective agreements with regulatory authorities about how specific types of changes will be implemented, what studies will support implementation, and what reporting category will apply when acceptance criteria are met. The PLCM document provides the index to these protocols.

Post-approval CMC commitments: Any commitments made to regulatory authorities during assessment—additional validation studies, monitoring programs, method improvements, process optimization plans—should be documented in the PLCM with timelines and expected completion. This addresses the common problem of commitments made during approval negotiations becoming lost or forgotten without systematic tracking.

The document is submitted initially with the marketing authorization application or via supplement/variation for marketed products when defining ECs. Following approval, the PLCM document should be updated in post-approval submissions for CMC changes, capturing how ECs have evolved and whether commitments have been fulfilled.

Location and Format Within Regulatory Submissions

The PLCM document can be located in eCTD Module 1 (regional administrative information), Module 2 (summaries), or Module 3 (quality information) based on regional regulatory preferences. The flexibility in location reflects that the PLCM document functions somewhat differently than traditional CTD sections—it’s a cross-reference and planning document rather than detailed technical information.

Module 3 placement (likely section 3.2.P.2 or 3.2.S.2 as part of pharmaceutical development discussions) positions the PLCM document alongside control strategy descriptions and process development narratives. This co-location makes logical sense—the PLCM represents the regulatory management strategy for the control strategy and process described in those sections.

Module 2 placement (within quality overall summary sections) positions the PLCM as summary-level strategic document, which aligns with its function as a high-level map rather than detailed specification.

Module 1 placement reflects that the PLCM document contains primarily regulatory process information (reporting categories, commitments) rather than scientific/technical content.

In practice, consultation with regional regulatory authorities during development or pre-approval meetings can clarify preferred location. The critical requirement is consistency and findability—inspectors and assessors need to locate the PLCM document readily.

The tabular format recommended for key PLCM elements facilitates comprehension and maintenance. ICH Q12 Annex IF provides an illustrative example showing how ECs, reporting categories, justifications, PACMPs, and commitments might be organized in tabular structure. While this example shouldn’t be treated as prescriptive template, it demonstrates organizational principles: grouping by product attribute (drug substance vs. drug product), clustering related parameters, referencing detailed justifications in development sections rather than duplicating extensive text in the table.

Control Strategy: The Foundation From Which ECs Emerge

The PLCM document’s Established Conditions emerge from the control strategy developed during pharmaceutical development and refined through technology transfer and commercial manufacturing experience. Understanding how PLCM documents relate to control strategy requires understanding what control strategies are, how they evolve across the lifecycle, and which control strategy elements become ECs versus remaining internal quality system controls.

ICH Q10 defines control strategy as “a planned set of controls, derived from current product and process understanding, that assures process performance and product quality”. This deceptively simple definition encompasses extensive complexity. The “planned set of controls” includes multiple layers:

- Controls on material attributes: Specifications and acceptance criteria for starting materials, excipients, drug substance, intermediates, and packaging components. These controls ensure incoming materials possess the attributes necessary for the manufacturing process to perform as designed and the final product to meet quality standards.

- Controls on the manufacturing process: Process parameter ranges, operating conditions, sequence of operations, and in-process controls that govern how materials are transformed into drug product. These include both parameters that operators actively control (temperatures, pressures, mixing speeds, flow rates) and parameters that are monitored to verify process state (pH, conductivity, particle counts).

- Controls on drug substance and drug product: Release specifications, stability monitoring programs, and testing strategies that verify the final product meets all quality requirements before distribution and maintains quality throughout its shelf life.

- Controls implicit in process design: Elements like sequence of unit operations, order of addition, purification step selection that aren’t necessarily “controlled” in real-time but represent design decisions that assure quality. A viral inactivation step positioned after affinity chromatography but before polishing steps exemplifies implicit control—the sequence matters for process performance but isn’t a parameter operators adjust batch-to-batch.

- Environmental and facility controls: Clean room classifications, environmental monitoring programs, utilities qualification, equipment maintenance, and calibration that create the context within which manufacturing occurs.

The control strategy is not a single document. It’s distributed across process descriptions, specifications, SOPs, batch records, validation protocols, equipment qualification protocols, environmental monitoring programs, stability protocols, and analytical methods. What makes these disparate elements a “strategy” is that they collectively and systematically address how Critical Quality Attributes are ensured within appropriate limits throughout manufacturing and shelf life.

Control Strategy Development During Pharmaceutical Development

Control strategies don’t emerge fully formed at the end of development. They evolve systematically as product and process understanding grows.

Early development focuses on identifying what quality attributes matter. The Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) articulates intended product performance, dosage form, route of administration, strength, stability, and quality characteristics necessary for safety and efficacy. From QTPP, potential Critical Quality Attributes are identified—the physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that should be controlled within appropriate limits to ensure product quality.

For a monoclonal antibody therapeutic, potential CQAs might include: protein concentration, high molecular weight species (aggregates), low molecular weight species (fragments), charge variants, glycosylation profile, host cell protein levels, host cell DNA levels, viral safety, endotoxin levels, sterility, particulates, container closure integrity. Not all initially identified quality attributes prove critical upon investigation, but systematic evaluation determines which attributes genuinely impact safety or efficacy versus which can vary without meaningful consequence.

Risk assessment identifies which formulation components and process steps might impact these CQAs. For attributes confirmed as critical, development studies characterize how material attributes and process parameters affect CQA levels. Design of Experiments (DoE), mechanistic models, scale-down models, and small-scale studies explore parameter space systematically.

This characterization reveals Critical Material Attributes (CMAs)—characteristics of input materials that impact CQAs when varied—and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs)—process variables that affect CQAs. For our monoclonal antibody, CMAs might include cell culture media glucose concentration (affects productivity and glycosylation), excipient sources (affect aggregation propensity), and buffer pH (affects stability). CPPs might include bioreactor temperature, pH control strategy, harvest timing, chromatography load density, viral inactivation pH and duration, ultrafiltration/diafiltration concentration factors.

The control strategy emerges from this understanding. CMAs become specifications on incoming materials. CPPs become controlled process parameters with defined operating ranges in batch records. CQAs become specifications with appropriate acceptance criteria. Process analytical technology (PAT) or in-process testing provides real-time verification that process state aligns with expectations. Design spaces, when established, define multidimensional regions where input variables and process parameters consistently deliver quality.

Control Strategy Evolution Through Technology Transfer and Commercial Manufacturing

The control strategy at approval represents best understanding achieved during development and clinical manufacturing. Technology transfer to commercial manufacturing sites tests whether that understanding transfers successfully—whether commercial-scale equipment, commercial facility environments, and commercial material sourcing produce equivalent product quality when operating within the established control strategy.

Technology transfer frequently reveals knowledge gaps. Small-scale bioreactors used for clinical supply might achieve adequate oxygen transfer through simple impeller agitation; commercial-scale 20,000L bioreactors require sparging strategy design considering bubble size, gas flow rates, and pressure control that weren’t critical at smaller scale. Heat transfer dynamics differ between 200L and 2000L vessels, affecting cooling/heating rates and potentially impacting CQAs sensitive to temperature excursions. Column packing procedures validated on 10cm diameter columns at development scale might not translate directly to 80cm diameter columns at commercial scale.

These discoveries during scale-up, process validation, and early commercial manufacturing build on development knowledge. Process characterization at commercial scale, continued process verification, and manufacturing experience over initial production batches refine understanding of which parameters truly drive quality versus which development-scale sensitivities don’t manifest at commercial scale.

The control strategy should evolve to reflect this learning. Parameters initially controlled tightly based on limited understanding might be relaxed when commercial experience demonstrates wider ranges maintain quality. Parameters not initially recognized as critical might be added when commercial-scale phenomena emerge. In-process testing strategies might shift from extensive sampling to targeted critical points when process capability is demonstrated.

ICH Q10 explicitly envisions this evolution, describing pharmaceutical quality system objectives that include “establishing and maintaining a state of control” and “facilitating continual improvement”. The state of control isn’t static—it’s dynamic equilibrium where process understanding, monitoring, and control mechanisms maintain product quality while enabling adaptation as knowledge grows.

Connecting Control Strategy to PLCM Document: Which Elements Become Established Conditions?

The control strategy contains far more elements than should be Established Conditions. This is where the conceptual distinction between control strategy (comprehensive quality assurance approach) and Established Conditions (regulatory commitments requiring submission if changed) becomes critical.

Not all controls necessary to assure quality need regulatory approval before changing. Organizations should continuously improve control strategies based on growing knowledge, without regulatory approval creating barriers to enhancement. The challenge is determining which controls are so fundamental to quality assurance that regulatory oversight of changes is appropriate versus which controls can be managed through pharmaceutical quality systems without regulatory involvement.

ICH Q12 guidance indicates that EC designation should consider:

- Criticality to product quality: Controls directly governing CQAs or CPPs/CMAs with demonstrated impact on CQAs are candidates for EC status. Release specifications for CQAs clearly merit EC designation—changing acceptance criteria for aggregates in a protein therapeutic affects patient safety and product efficacy directly. Similarly, critical process parameters with demonstrated CQA impact warrant EC consideration.

- Level of quality risk: High-risk controls where inappropriate change could compromise patient safety should be ECs with prior approval reporting category. Moderate-risk controls might be ECs with notification reporting category. Low-risk controls might not need EC designation.

- Product and process understanding: Greater understanding enables more nuanced EC identification. When extensive characterization demonstrates certain parameters have minimal quality impact, justification exists for excluding them from ECs. Conversely, limited understanding argues for conservative EC designation until further characterization enables refinement.

- Regulatory expectations and precedent: While ICH Q12 harmonizes approaches, regional regulatory expectations still influence EC identification strategy. Conservative regulators might expect more extensive EC designation; progressive regulators comfortable with risk-based approaches might accept narrower EC scope when justified.

Consider our monoclonal antibody purification process control strategy. The comprehensive control strategy includes:

- Column resin specifications (purity, dynamic binding capacity, lot-to-lot variability limits)

- Column packing procedures (compression force, bed height uniformity testing, packing SOPs)

- Buffer preparation procedures (component specifications, pH verification, bioburden limits)

- Equipment qualification status (chromatography skid IQ/OQ/PQ, automated systems validation)

- Process parameters (load density, flow rates, gradient slopes, pool collection criteria)

- In-process testing (pool purity analysis, viral clearance sample retention)

- Environmental monitoring in manufacturing suite

- Operator training qualification

- Cleaning validation for equipment between campaigns

- Batch record templates documenting execution

- Investigation procedures when deviations occur

Which elements become ECs in the PLCM document?

Using enhanced parameter-based approach with substantial process understanding: Resin specifications for critical attributes (dynamic binding capacity range, leachables below limits) likely merit EC designation—changing resin characteristics affects purification performance and CQA delivery. Load density ranges and pool collection criteria based on specific quality specifications probably merit EC status given their direct connection to product purity and yield. Critical buffer component specifications affecting pH and conductivity (which impact protein behavior on resins) warrant EC consideration.

Buffer preparation SOPs, equipment qualification procedures, environmental monitoring program details, operator training qualification criteria, cleaning validation acceptance criteria, and batch record templates likely don’t require EC designation despite being essential control strategy elements. These controls matter for quality, but changes can be managed through pharmaceutical quality system change control with appropriate impact assessment, validation where needed, and implementation without regulatory notification.

The PLCM document makes these distinctions explicit. The control strategy summary section acknowledges that comprehensive controls exist beyond those designated ECs. The EC listing table specifies which elements are ECs, referencing detailed justifications in development sections. The reporting category column indicates whether EC changes require prior approval (drug substance concentration specification), notification (resin dynamic binding capacity specification range adjustment based on additional characterization), or PQS management only (parameters within approved design space).

How ICH Q12 Tools Integrate Into Overall Lifecycle Management

The PLCM document serves as integrating framework for ICH Q12’s lifecycle management tools: Established Conditions, Post-Approval Change Management Protocols, reporting category assignments, and pharmaceutical quality system enablement.

Post-Approval Change Management Protocols: Planning Future Changes Prospectively

PACMPs address a fundamental lifecycle management challenge: regulatory authorities assess change appropriateness when changes are proposed, but this reactive assessment creates timeline uncertainty and resource inefficiency. Organizations proposing manufacturing site additions, analytical method improvements, or process optimizations submit change supplements, then wait months or years for assessment and approval while maintaining existing less-optimal approaches.

PACMPs flip this dynamic by obtaining prospective agreement on how anticipated changes will be implemented and assessed. The PACMP submitted in the original application or post-approval supplement describes:

- The change intended for future implementation (e.g., manufacturing site addition, scale-up to larger bioreactors, analytical method improvement)

- Rationale for the change (capacity expansion, technology improvement, continuous improvement)

- Studies and validation work that will support change implementation

- Acceptance criteria that will demonstrate the change maintains product quality

- Proposed reporting category when acceptance criteria are met

If regulatory authorities approve the PACMP, the organization can implement the described change when studies meet acceptance criteria, reporting results per the agreed category rather than defaulting to conservative prior approval submission. This dramatically improves predictability—the organization knows in advance what studies will suffice and what reporting timeline applies.

For example, a PACMP might propose adding manufacturing capacity at a second site using identical equipment and procedures. The protocol specifies: three engineering runs demonstrating equipment performs comparably; analytical comparability studies showing product quality matches reference site; process performance qualification demonstrating commercial batches meet specifications; stability studies confirming comparable stability profiles. When these acceptance criteria are met, implementation proceeds via notification rather than prior approval supplement.

The PLCM document references approved PACMPs, providing the index to these prospectively planned changes. During regulatory inspections or when implementing changes, the PLCM document directs inspectors and internal change control teams to the relevant protocol describing the agreed implementation approach.

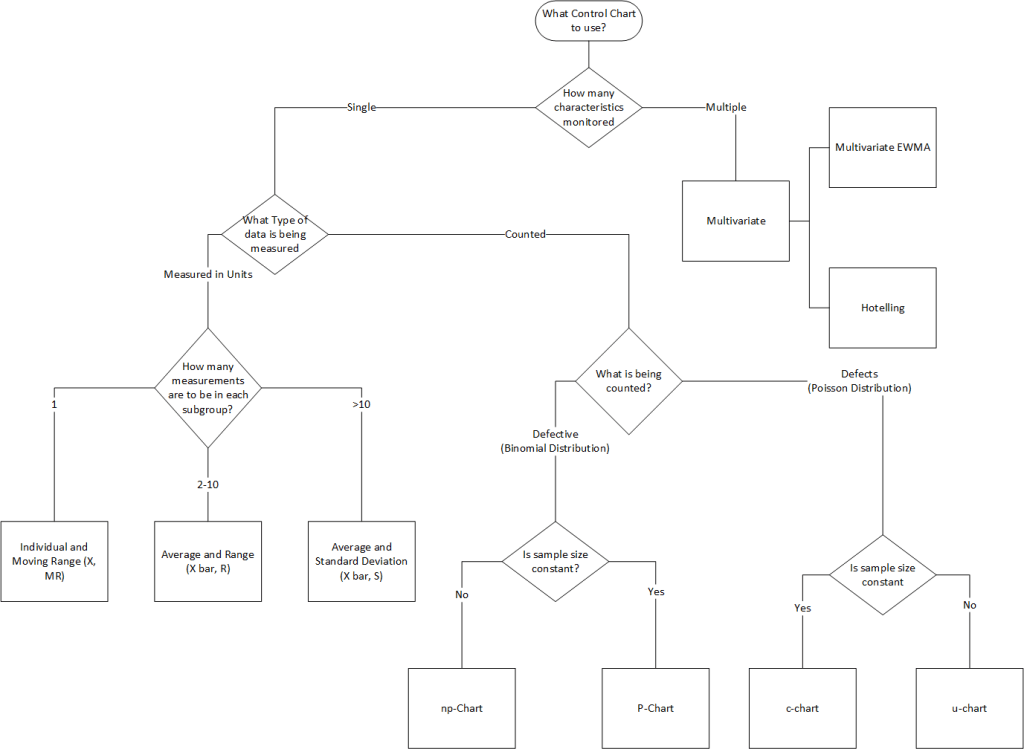

Reporting Categories: Risk-Based Regulatory Oversight

Reporting category assignment represents ICH Q12’s mechanism for aligning regulatory oversight intensity with quality risk. Not all changes merit identical regulatory scrutiny. Changes with high potential patient impact warrant prior approval before implementation. Changes with moderate impact might warrant notification so regulators are aware but don’t need to approve prospectively. Changes with minimal quality risk can be managed through pharmaceutical quality systems without regulatory notification (though inspection verification remains possible).

ICH Q12 encourages risk-based categorization aligned with regional regulatory frameworks while enabling flexibility when justified by product/process understanding and robust PQS. The PLCM document makes categorization explicit and provides justification.

Traditional US framework defines three reporting categories per 21 CFR 314.70:

- Major changes (prior approval supplement): Changes requiring FDA approval before distribution of product made using the change. Examples include formulation changes affecting bioavailability, new manufacturing sites, significant manufacturing process changes, specification relaxations for CQAs. These changes present high quality risk; regulatory assessment verifies that proposed changes maintain safety and efficacy.

- Moderate changes (Changes Being Effected or notification): Changes implemented after submission but before FDA approval (CBE-30: 30 days after submission) or notification to FDA without awaiting approval. Examples include analytical method changes, minor formulation adjustments, supplier changes for non-critical materials. Quality risk is manageable; notification ensures regulatory awareness while avoiding unnecessary delay.

- Minor changes (annual report): Changes reported annually without prior notification. Examples include editorial corrections, equipment replacement with comparable equipment, supplier changes for non-critical non-functional components. Quality risk is minimal; annual aggregation reduces administrative burden while maintaining regulatory visibility.

European variation regulations provide comparable framework with Type IA (notification), Type IB (notification with delayed implementation), and Type II (approval required) variations.

ICH Q12 enables movement beyond default categorization through justified proposals based on product understanding, process characterization, and PQS effectiveness. A change that would traditionally require prior approval might justify notification category when:

- Extensive process characterization demonstrates the change remains within validated design space

- Comparability studies show equivalent product quality

- Robust PQS ensures appropriate impact assessment and validation before implementation

- PACMP established prospectively agreed acceptance criteria

The PLCM document documents these justified categorizations alongside conservative defaults, creating transparency about lifecycle management approach. When organizations propose that specific EC changes merit notification rather than prior approval based on process understanding, the PLCM provides the location for that proposal and cross-references to supporting justification in development sections.

Pharmaceutical Quality System: The Foundation Enabling Flexibility

None of the ICH Q12 tools—ECs, PACMPs, reporting categories, PLCM documents—function effectively without robust pharmaceutical quality system foundation. The PQS provides the infrastructure ensuring that changes not requiring regulatory notification are nevertheless managed with appropriate rigor.

ICH Q10 describes PQS as the comprehensive framework spanning the entire lifecycle from pharmaceutical development through product discontinuation, with objectives including achieving product realization, establishing and maintaining state of control, and facilitating continual improvement. The PQS elements—process performance monitoring, corrective and preventive action, change management, management review—provide systematic mechanisms for managing all changes (not just those notified to regulators).

When the PLCM document indicates that certain parameters can be adjusted within design space without regulatory notification, the PQS change management system ensures those adjustments undergo appropriate impact assessment, scientific justification, implementation with validation where needed, and effectiveness verification. When parameters are adjusted within specification ranges based on process optimization, CAPA systems ensure changes address identified opportunities while monitoring systems verify maintained quality.

Regulatory inspectors assessing ICH Q12 implementation evaluate PQS effectiveness as much as PLCM document content. An impressive PLCM document with sophisticated EC identification and justified reporting categories means little if the PQS change management system can’t demonstrate appropriate rigor for changes managed internally. Conversely, organizations with robust PQS can justify greater regulatory flexibility because inspectors have confidence that internal management substitutes effectively for regulatory oversight.

The Lifecycle Perspective: PLCM Documents as Living Infrastructure

The PLCM document concept fails if treated as static submission artifact—a form populated during regulatory preparation then filed away after approval. The document’s value emerges from functioning as living infrastructure maintained throughout commercial lifecycle.

Pharmaceutical Development Stage: Establishing Initial PLCM

During pharmaceutical development (ICH Q10’s first lifecycle stage), the focus is designing products and processes that consistently deliver intended performance. Development activities using QbD principles, risk management, and systematic characterization generate the product and process understanding that enables initial control strategy design and EC identification.

At this stage, the PLCM document represents the lifecycle management strategy proposed to regulatory authorities. Development teams compile:

- Control strategy summary articulating how CQAs will be ensured through material controls, process controls, and testing strategy

- Proposed EC listing based on available understanding and chosen approach (minimal, enhanced parameter-based, or performance-based)

- Reporting category proposals justified by development studies and risk assessment

- Any PACMPs for changes anticipated during commercialization (site additions, scale-up, method improvements)

- Commitments for post-approval work (additional validation studies, monitoring programs, process characterization to be completed commercially)

The quality of this initial PLCM document depends heavily on development quality. Products developed with minimal process characterization and traditional empirical approaches produce conservative PLCM documents—extensive ECs, default prior approval reporting categories, limited justification for flexibility. Products developed with extensive QbD, comprehensive characterization, and demonstrated design spaces produce strategic PLCM documents—targeted ECs, risk-based reporting categories, justified flexibility.

This creates powerful incentive alignment. QbD investment during development isn’t merely about satisfying reviewers or demonstrating scientific sophistication—it’s infrastructure investment enabling lifecycle flexibility that delivers commercial value through reduced regulatory burden, faster implementation of improvements, and supply chain agility.

Technology Transfer Stage: Testing and Refining PLCM Strategy

Technology transfer represents critical validation of whether development understanding and proposed control strategy transfer successfully to commercial manufacturing. This stage tests the PLCM strategy implicitly—do the identified ECs actually ensure quality at commercial scale? Are proposed reporting categories appropriate for the change types that emerge during scale-up?

Technology transfer frequently reveals refinements needed. Parameters identified as critical at development scale might prove less sensitive commercially due to different equipment characteristics. Parameters not initially critical might require tighter control at larger scale due to heat/mass transfer limitations, longer processing times, or equipment-specific phenomena.

These discoveries should inform PLCM document updates submitted with first commercial manufacturing supplements or variations. The EC listing might be refined based on scale-up learning. Reporting category proposals might be adjusted when commercial-scale validation provides different risk perspectives. PACMPs initially proposed might require modification when commercial manufacturing reveals implementation challenges not apparent from development-scale thinking.

Organizations treating the PLCM as static approval-time artifact miss this refinement opportunity. The PLCM document approved initially reflected best understanding available during development. Commercial manufacturing generates new understanding that should enhance the PLCM, making it more accurate and strategic.

Commercial Manufacturing Stage: Maintaining PLCM as Living Document

Commercial manufacturing represents the longest lifecycle stage, potentially spanning decades. During this period, the PLCM document should evolve continuously as the product evolves.

Post-approval changes occur constantly in pharmaceutical manufacturing. Supplier discontinuations force raw material changes. Equipment obsolescence requires replacement. Analytical methods improve as technology advances. Process optimizations based on manufacturing experience enhance efficiency or robustness. Regulatory standard evolution necessitates updated validation approaches or expanded testing.

Each change potentially affects the PLCM document. If an EC changes, the PLCM document should be updated to reflect the new approved state. If a PACMP is executed and the change implemented, the PLCM should document completion and remove that protocol from active status while adding the implemented change to the EC listing if it becomes a new EC. If post-approval commitments are fulfilled, the PLCM should document completion.

The PLCM document becomes the central change management reference. When change controls propose manufacturing modifications, the first question is: “Does this affect an Established Condition in our PLCM document?” If yes, what’s the reporting category? Do we have an approved PACMP covering this change type? If we’re proposing this change doesn’t require regulatory notification despite affecting described elements, what’s our justification based on design space, process understanding, or risk assessment?

Annual Product Reviews, Management Reviews, and change management metrics should assess PLCM document currency. How many changes implemented last year affected ECs? What reporting categories were used? Were reporting category assignments appropriate retrospectively based on actual quality impact? Are there patterns suggesting EC designation should be refined—parameters initially identified as critical that commercial experience shows have minimal impact, or vice versa?

This dynamic maintenance transforms the PLCM document from regulatory artifact into operational tool for lifecycle management strategy. The document evolves from initial approval state toward increasingly sophisticated representation of how the organization manages quality through knowledge-based, risk-informed change management rather than rigid adherence to initial approval conditions.

Practical Implementation Challenges: PLCM-as-Done Versus PLCM-as-Imagined

The conceptual elegance of PLCM documents—central repository for lifecycle management strategy, transparent communication with regulators, strategic enabler for post-approval flexibility—confronts implementation reality in pharmaceutical organizations struggling with resource constraints, competing priorities, and cultural inertia favoring traditional approaches.

The Knowledge Gap: Insufficient Understanding to Support Enhanced EC Approaches

Many pharmaceutical organizations implementing ICH Q12 confront applications containing limited process characterization. Products approved years or decades ago described manufacturing processes in detail without the underlying DoE studies, mechanistic models, or design space characterization that would support enhanced EC identification.

The submitted information implies everything might be critical because systematic demonstrations of non-criticality don’t exist. Implementing PLCM documents for these legacy products forces uncomfortable choice: designate extensive ECs based on conservative interpretation (accepting reduced post-approval flexibility), or invest in retrospective characterization studies generating understanding needed to justify refined EC identification.

The latter option represents significant resource commitment. Process characterization at commercial scale requires manufacturing capacity allocation, analytical testing resources, statistical expertise for DoE design and interpretation, and time for study execution and assessment. For products with mature commercial manufacturing, this investment competes with new product development, existing product improvements, and operational firefighting.

Organizations often default to conservative EC designation for legacy products, accepting reduced ICH Q12 benefits rather than making characterization investment. This creates two-tier environment: new products developed with QbD approaches achieving ICH Q12 flexibility, while legacy products remain constrained by limited understanding despite being commercially mature.

The strategic question is whether retrospective characterization investment pays back through avoided regulatory submission costs, faster implementation of supply chain changes, and enhanced resilience during material shortages or supplier disruptions. For high-value products with long remaining commercial life, the investment frequently justifies itself. For products approaching patent expiration or with declining volumes, the business case weakens.

The Cultural Gap: Change Management as Compliance Versus Strategic Capability

Traditional pharmaceutical change management culture treats post-approval changes as compliance obligations requiring regulatory permission rather than strategic capabilities enabling continuous improvement. This mindset manifests in change control processes designed to document what changed and ensure regulatory notification rather than optimize change implementation efficiency.

ICH Q12 requires cultural shift from “prove we complied with regulatory notification requirements” toward “optimize lifecycle management strategy balancing quality assurance with operational agility”. This shift challenges embedded assumptions.

The assumption that “more regulatory oversight equals better quality” must confront evidence that excessive regulatory burden can harm quality by preventing necessary improvements, forcing workarounds when optimal changes can’t be implemented due to submission timelines, and creating perverse incentives against process optimization. Quality emerges from robust understanding, effective control, and systematic improvement—not from regulatory permission slips for every adjustment.

The assumption that “regulatory submission requirements are fixed by regulation” must acknowledge that ICH Q12 explicitly encourages justified proposals for risk-based reporting categories differing from traditional defaults. Organizations can propose that specific changes merit notification rather than prior approval based on process understanding, comparability demonstrations, and PQS rigor. But proposing non-default categorization requires confidence to articulate justification and defend during regulatory assessment—confidence many organizations lack.

Building this capability requires training quality professionals, regulatory affairs teams, and change control reviewers in ICH Q12 concepts and their application. It requires developing organizational competency in risk assessment connecting change types to quality impact with quantitative or semi-quantitative justification. It requires quality systems that can demonstrate to inspectors that internally managed changes undergo appropriate rigor even without regulatory oversight.

The Maintenance Gap: PLCM Documents as Static Approval Artifacts Versus Living Systems

Perhaps the largest implementation gap exists between PLCM documents as living lifecycle management infrastructure versus PLCM documents as one-time regulatory submission artifacts. Pharmaceutical organizations excel at generating documentation for regulatory submissions. We struggle with maintaining dynamic documents that evolve with the product.

The PLCM document submitted at approval captures understanding and strategy at that moment. Absent systematic maintenance processes, the document fossilizes. Post-approval changes occur but the PLCM document isn’t updated to reflect current EC state. PACMPs are executed but completion isn’t documented in updated PLCM versions. Commitments are fulfilled but the PLCM document continues listing them as pending.

Within several years, the PLCM document submitted at approval no longer accurately represents current product state or lifecycle management approach. When inspectors request the PLCM document, organizations scramble to reconstruct current state from change control records, approval letters, and variation submissions rather than maintaining the PLCM proactively.

This failure emerges from treating PLCM documents as regulatory submission deliverables (owned by regulatory affairs, prepared for submission, then archived) rather than operational quality system documents (owned by quality systems, maintained continuously, used routinely for change management decisions). The latter requires infrastructure:

- Document management systems with version control and change history

- Assignment of PLCM document maintenance responsibility to specific quality system roles

- Integration of PLCM updates into change control workflows (every approved change affecting ECs triggers PLCM update)

- Periodic PLCM review during annual product reviews or management reviews to verify currency

- Training for quality professionals in using PLCM documents as operational references rather than dusty submission artifacts

Organizations implementing ICH Q12 successfully build these infrastructure elements deliberately. They recognize that PLCM document value requires maintenance investment comparable to batch record maintenance, specification maintenance, or validation protocol maintenance—not one-time preparation then neglect.

Strategic Implications: PLCM Documents as Quality System Maturity Indicators

The quality and maintenance of PLCM documents reveals pharmaceutical quality system maturity. Organizations with immature quality systems produce PLCM documents that check regulatory boxes—listing ECs comprehensively with conservative reporting categories, acknowledging required elements, fulfilling submission expectations. But these PLCM documents provide minimal strategic value because they reflect compliance obligation rather than lifecycle management strategy.

Organizations with mature quality systems produce PLCM documents demonstrating sophisticated lifecycle thinking: targeted EC identification justified by process understanding, risk-based reporting category proposals supported by characterization data and PQS capabilities, PACMPs anticipating future manufacturing evolution, and maintained currency through systematic update processes integrated into quality system operations.

This maturity manifests in tangible outcomes. Mature organizations implement post-approval improvements faster because PLCM planning anticipated change types and established appropriate reporting categories. They navigate supplier changes and material shortages more effectively because EC scope acknowledges design space flexibility rather than rigid specification adherence. They demonstrate regulatory inspection resilience because inspectors reviewing PLCM documents find coherent lifecycle strategy supported by robust PQS rather than afterthought compliance artifacts.

The PLCM document, implemented authentically, becomes what it was intended to be: central infrastructure connecting product understanding, control strategy design, risk management, quality systems, and regulatory strategy into integrated lifecycle management capability. Not another form to complete during regulatory preparation, but the strategic framework enabling pharmaceutical organizations to manage commercial manufacturing evolution over decades while assuring consistent product quality and maintaining regulatory compliance.

That’s what ICH Q12 envisions. That’s what the pharmaceutical industry needs. The gap between vision and reality—between PLCM-as-imagined and PLCM-as-done—determines whether these tools transform pharmaceutical lifecycle management or become another layer of regulatory theater generating compliance artifacts without operational value.

Closing that gap requires the same fundamental shift quality culture always requires: moving from procedure compliance and documentation theater toward genuine capability development grounded in understanding, measurement, and continuous improvement. PLCM documents that work emerge from organizations committed to product understanding, lifecycle strategy, and quality system maturity—not from organizations populating templates because ICH Q12 says we should have these documents.

Which type of organization are we building? The answer appears not in the eloquence of our PLCM document prose, but in whether our change control groups reference these documents routinely, whether our annual product reviews assess PLCM currency systematically, whether our quality professionals can articulate EC rationale confidently, and whether our post-approval changes implement predictably because lifecycle planning anticipated them rather than treating each change as crisis requiring regulatory archeology.

PLCM documents are falsifiable quality infrastructure. They make specific predictions: that identified ECs capture elements necessary for quality assurance, that reporting categories align with actual quality risk, that PACMPs enable anticipated changes efficiently, that PQS provides appropriate rigor for internally managed changes. These predictions can be tested through change implementation experience, regulatory inspection outcomes, supply chain resilience during disruptions, and cycle time metrics for post-approval changes.

Organizations serious about pharmaceutical lifecycle management should test these predictions systematically. If PLCM strategies prove ineffective—if supposedly non-critical parameters actually impact quality when changed, if reporting categories prove inappropriate, if PQS rigor proves insufficient for internally managed changes—that’s valuable information demanding revision. If PLCM strategies prove effective, that validates the lifecycle management approach and builds confidence for further refinement.

Most organizations won’t conduct this rigorous testing. PLCM documents will become another compliance artifact, accepted uncritically as required elements without empirical validation of effectiveness. This is exactly the kind of unfalsifiable quality system I’ve critiqued throughout this blog. Genuine commitment to lifecycle management requires honest measurement of whether ICH Q12 tools actually improve lifecycle management outcomes.

The pharmaceutical industry deserves better. Patients deserve better. We can build lifecycle management infrastructure that actually manages lifecycles—or we can generate impressive documents that impress nobody except those who’ve never tried using them for actual change management decisions.