In manufacturing circles, “First-Time Right” (FTR) has become something of a sacred cow-a philosophy so universally accepted that questioning it feels almost heretical. Yet as continuous manufacturing processes increasingly replace traditional batch production, we need to critically examine whether this cherished doctrine serves us well or creates dangerous blind spots in our quality assurance frameworks.

The Seductive Promise of First-Time Right

Let’s start by acknowledging the compelling appeal of FTR. As commonly defined, First-Time Right is both a manufacturing principle and KPI that denotes the percentage of end-products leaving production without quality defects. The concept promises a manufacturing utopia: zero waste, minimal costs, maximum efficiency, and delighted customers receiving perfect products every time.

The math seems straightforward. If you produce 1,000 units and 920 are defect-free, your FTR is 92%. Continuous improvement efforts should steadily drive that percentage upward, reducing the resources wasted on imperfect units.

This principle finds its intellectual foundation in Six Sigma methodology, which can tend to give it an air of scientific inevitability. Yet even Six Sigma acknowledges that perfection remains elusive. This subtle but crucial nuance often gets lost when organizations embrace FTR as an absolute expectation rather than an aspiration.

First-Time Right in biologics drug substance manufacturing refers to the principle and performance metric of producing a biological drug substance that meets all predefined quality attributes and regulatory requirements on the first attempt, without the need for rework, reprocessing, or batch rejection. In this context, FTR emphasizes executing each step of the complex, multi-stage biologics manufacturing process correctly from the outset-starting with cell line development, through upstream (cell culture/fermentation) and downstream (purification, formulation) operations, to the final drug substance release.

Achieving FTR is especially challenging in biologics because these products are made from living systems and are highly sensitive to variations in raw materials, process parameters, and environmental conditions. Even minor deviations can lead to significant quality issues such as contamination, loss of potency, or batch failure, often requiring the entire batch to be discarded.

In biologics manufacturing, FTR is not just about minimizing waste and cost; it is critical for patient safety, regulatory compliance, and maintaining supply reliability. However, due to the inherent variability and complexity of biologics, FTR is best viewed as a continuous improvement goal rather than an absolute expectation. The focus is on designing and controlling processes to consistently deliver drug substances that meet all critical quality attributes-recognizing that, despite best efforts, some level of process variation and deviation is inevitable in biologics production

The Unique Complexities of Continuous Manufacturing

Traditional batch processing creates natural boundaries-discrete points where production pauses, quality can be assessed, and decisions about proceeding can be made. In contrast, continuous manufacturing operates without these convenient checkpoints, as raw materials are continuously fed into the manufacturing system, and finished products are continuously extracted, without interruption over the life of the production run.

This fundamental difference requires a complete rethinking of quality assurance approaches. In continuous environments:

- Quality must be monitored and controlled in real-time, without stopping production

- Deviations must be detected and addressed while the process continues running

- The interconnected nature of production steps means issues can propagate rapidly through the system

- Traceability becomes vastly more complex

Regulatory agencies recognize these unique challenges, acknowledging that understanding and managing risks is central to any decision to greenlight CM in a production-ready environment. When manufacturing processes never stop, quality assurance cannot rely on the same methodologies that worked for discrete batches.

The Dangerous Complacency of Perfect-First-Time Thinking

The most insidious danger of treating FTR as an achievable absolute is the complacency it breeds. When leadership becomes fixated on achieving perfect FTR scores, several dangerous patterns emerge:

Overconfidence in Automation

While automation can significantly improve quality, it is important to recognize the irreplaceable value of human oversight. Automated systems, no matter how advanced, are ultimately limited by their programming, design, and maintenance. Human operators bring critical thinking, intuition, and the ability to spot subtle anomalies that machines may overlook. A vigilant human presence can catch emerging defects or process deviations before they escalate, providing a layer of judgment and adaptability that automation alone cannot replicate. Relying solely on automation creates a dangerous blind spot-one where the absence of human insight can allow issues to go undetected until they become major problems. True quality excellence comes from the synergy of advanced technology and engaged, knowledgeable people working together.

Underinvestment in Deviation Management

If perfection is expected, why invest in systems to handle imperfections? Yet robust deviation management-the processes used to identify, document, investigate, and correct deviations becomes even more critical in continuous environments where problems can cascade rapidly. Organizations pursuing FTR often underinvest in the very systems that would help them identify and address the inevitable deviations.

False Sense of Process Robustness

Process robustness refers to the ability of a manufacturing process to tolerate the variability of raw materials, process equipment, operating conditions, environmental conditions and human factors. An obsession with FTR can mask underlying fragility in processes that appear to be performing well under normal conditions. When we pretend our processes are infallible, we stop asking critical questions about their resilience under stress.

Quality Culture Deterioration

When FTR becomes dogma, teams may become reluctant to report or escalate potential issues, fearing they’ll be seen as failures. This creates a culture of silence around deviations-precisely the opposite of what’s needed for effective quality management in continuous manufacturing. When perfection is the only acceptable outcome, people hide imperfections rather than address them.

Magical Thinking in Quality Management

The belief that we can eliminate all errors in complex manufacturing processes amounts to what organizational psychologists call “magical thinking” – the delusional belief that one can do the impossible. In manufacturing, this often manifests as pretending that doing more tasks with less resources will not hurt the work quality.

This is a pattern I’ve observed repeatedly in my investigations of quality failures. When leadership subscribes to the myth that perfection is not just desirable but achievable, they create the conditions for quality disasters. Teams stop preparing for how to handle deviations and start pretending deviations won’t occur.

The irony is that this approach actually undermines the very goal of FTR. By acknowledging the possibility of failure and building systems to detect and learn from it quickly, we actually increase the likelihood of getting things right.

Building a Healthier Quality Culture for Continuous Manufacturing

Rather than chasing the mirage of perfect FTR, organizations should focus on creating systems and cultures that:

- Detect deviations rapidly: Continuous monitoring through advanced process control systems becomes essential for monitoring and regulating critical parameters throughout the production process. The question isn’t whether deviations will occur but how quickly you’ll know about them.

- Investigate transparently: When issues occur, the focus should be on understanding root causes rather than assigning blame. The culture must prioritize learning over blame.

- Implement robust corrective actions: Deviations should be thoroughly documented including details about when and where it occurred, who identified it, a detailed description of the nonconformance, initial actions taken, results of the investigation into the cause, actions taken to correct and prevent recurrence, and a final evaluation of the effectiveness of these actions.

- Learn systematically: Each deviation represents a valuable opportunity to strengthen processes and prevent similar issues in the future. The organization that learns fastest wins, not the one that pretends to be perfect.

Breaking the Groupthink Cycle

The FTR myth thrives in environments characterized by groupthink, where challenging the prevailing wisdom is discouraged. When leaders obsess over FTR metrics while punishing those who report deviations, they create the perfect conditions for quality disasters.

This connects to a theme I’ve explored repeatedly on this blog: the dangers of losing institutional memory and critical thinking in quality organizations. When we forget that imperfection is inevitable, we stop building the systems and cultures needed to manage it effectively.

Embracing Humility, Vigilance, and Continuous Learning

True quality excellence comes not from pretending that errors don’t occur, but from embracing a more nuanced reality:

- Perfection is a worthy aspiration but an impossible standard

- Systems must be designed not just to prevent errors but to detect and address them

- A healthy quality culture prizes transparency and learning over the appearance of perfection

- Continuous improvement comes from acknowledging and understanding imperfections, not denying them

The path forward requires humility to recognize the limitations of our processes, vigilance to catch deviations quickly when they occur, and an unwavering commitment to learning and improving from each experience.

In the end, the most dangerous quality issues aren’t the ones we detect and address-they’re the ones our systems and culture allow to remain hidden because we’re too invested in the myth that they shouldn’t exist at all. First-Time Right should remain an aspiration that drives improvement, not a dogma that blinds us to reality.

From Perfect to Perpetually Improving

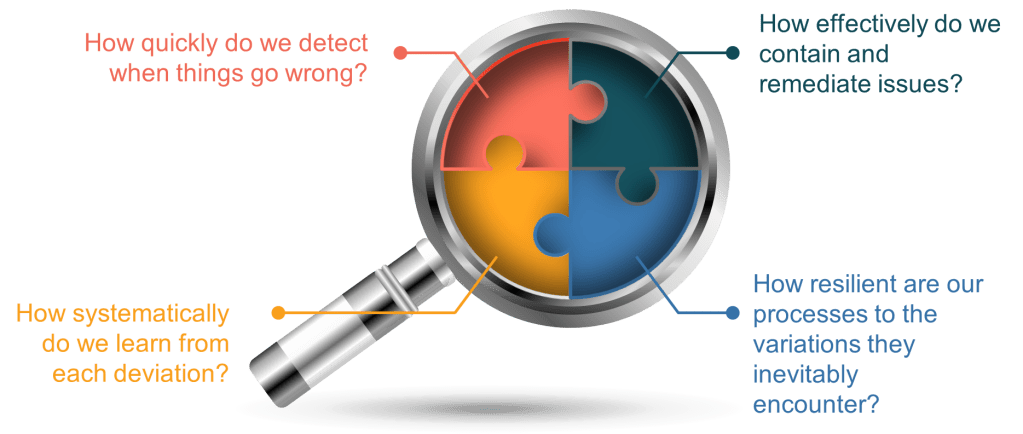

As continuous manufacturing becomes the norm rather than the exception, we need to move beyond the simplistic FTR myth toward a more sophisticated understanding of quality. Rather than asking, “Did we get it perfect the first time?” we should be asking:

- How quickly do we detect when things go wrong?

- How effectively do we contain and remediate issues?

- How systematically do we learn from each deviation?

- How resilient are our processes to the variations they inevitably encounter?

These questions acknowledge the reality of manufacturing-that imperfection is inevitable-while focusing our efforts on what truly matters: building systems and cultures capable of detecting, addressing, and learning from deviations to drive continuous improvement.

The companies that thrive in the continuous manufacturing future won’t be those with the most impressive FTR metrics on paper. They’ll be those with the humility to acknowledge imperfection, the systems to detect and address it quickly, and the learning cultures that turn each deviation into an opportunity for improvement.