Dr. Valerie Mulholland’s recent exploration of the GI Joe Bias strikes gets to the heart of a fundamental challenge in pharmaceutical quality management: the persistent belief that awareness of cognitive biases is sufficient to overcome them. I find Valerie’s analysis particularly compelling because it connects directly to the practical realities we face when implementing ICH Q9(R1)’s mandate to actively manage subjectivity in risk assessment.

Valerie’s observation that “awareness of a bias does little to prevent it from influencing our decisions” shows us that the GI Joe Bias underlays a critical gap between intellectual understanding and practical application—a gap that pharmaceutical organizations must bridge if they hope to achieve the risk-based decision-making excellence that ICH Q9(R1) demands.

The Expertise Paradox: Why Quality Professionals Are Particularly Vulnerable

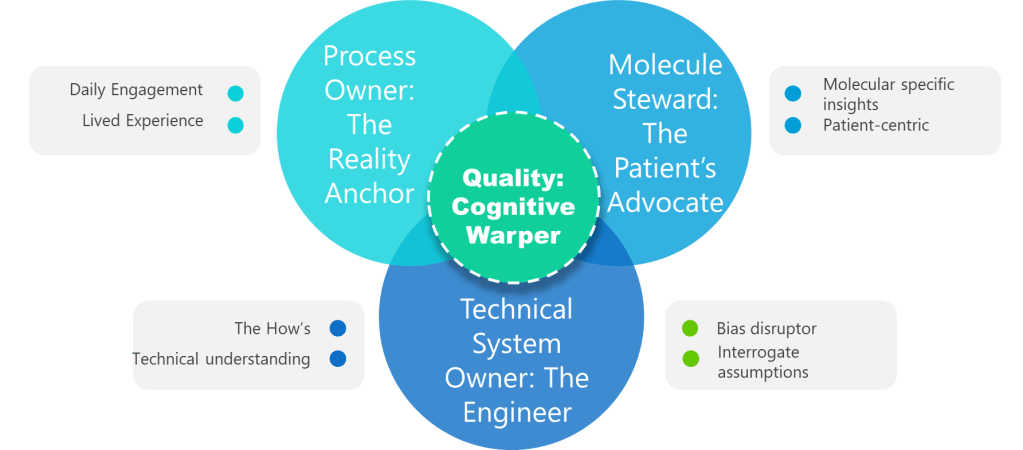

Valerie correctly identifies that quality risk management facilitators are often better at spotting biases in others than in themselves. This observation connects to a deeper challenge I’ve previously explored: the fallacy of expert immunity. Our expertise in pharmaceutical quality systems creates cognitive patterns that simultaneously enable rapid, accurate technical judgments while increasing our vulnerability to specific biases.

The very mechanisms that make us effective quality professionals—pattern recognition, schema-based processing, heuristic shortcuts derived from base rate experiences—are the same cognitive tools that generate bias. When I conduct investigations or facilitate risk assessments, my extensive experience with similar events creates expectations and assumptions that can blind me to novel failure modes or unexpected causal relationships. This isn’t a character flaw; it’s an inherent part of how expertise develops and operates.

Valerie’s emphasis on the need for trained facilitators in high-formality QRM activities reflects this reality. External facilitation isn’t just about process management—it’s about introducing cognitive diversity and bias detection capabilities that internal teams, no matter how experienced, cannot provide for themselves. The facilitator serves as a structured intervention against the GI Joe fallacy, embodying the systematic approaches that awareness alone cannot deliver.

From Awareness to Architecture: Building Bias-Resistant Quality Systems

The critical insight from both Valerie’s work and my writing about structured hypothesis formation is that effective bias management requires architectural solutions, not individual willpower. ICH Q9(R1)’s introduction of the “Managing and Minimizing Subjectivity” section represents recognition that regulatory compliance requires systematic approaches to cognitive bias management.

In my post on reducing subjectivity in quality risk management, I identified four strategies that directly address the limitations Valerie highlights about the GI Joe Bias:

- Leveraging Knowledge Management: Rather than relying on individual awareness, effective bias management requires systematic capture and application of objective information. When risk assessors can access structured historical data, supplier performance metrics, and process capability studies, they’re less dependent on potentially biased recollections or impressions.

- Good Risk Questions: The formulation of risk questions represents a critical intervention point. Well-crafted questions can anchor assessments in specific, measurable terms rather than vague generalizations that invite subjective interpretation. Instead of asking “What are the risks to product quality?”, effective risk questions might ask “What are the potential causes of out-of-specification dissolution results for Product X in the next 6 months based on the last three years of data?”

- Cross-Functional Teams: Valerie’s observation that we’re better at spotting biases in others translates directly into team composition strategies. Diverse, cross-functional teams naturally create the external perspective that individual bias recognition cannot provide. The manufacturing engineer, quality analyst, and regulatory specialist bring different cognitive frameworks that can identify blind spots in each other’s reasoning.

- Structured Decision-Making Processes: The tools Valerie mentions—PHA, FMEA, Ishikawa, bow-tie analysis—serve as external cognitive scaffolding that guides thinking through systematic pathways rather than relying on intuitive shortcuts that may be biased.

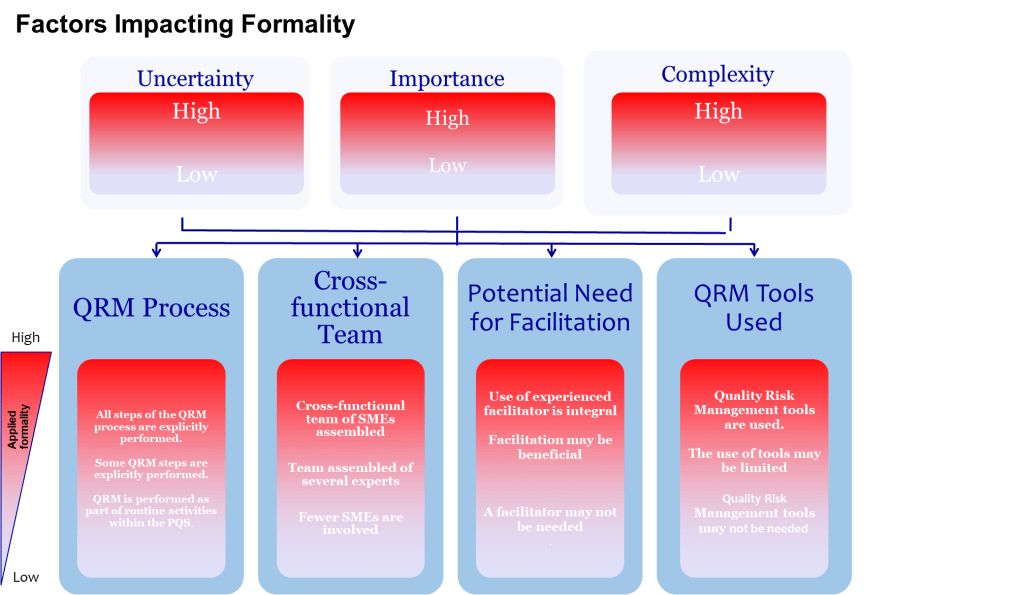

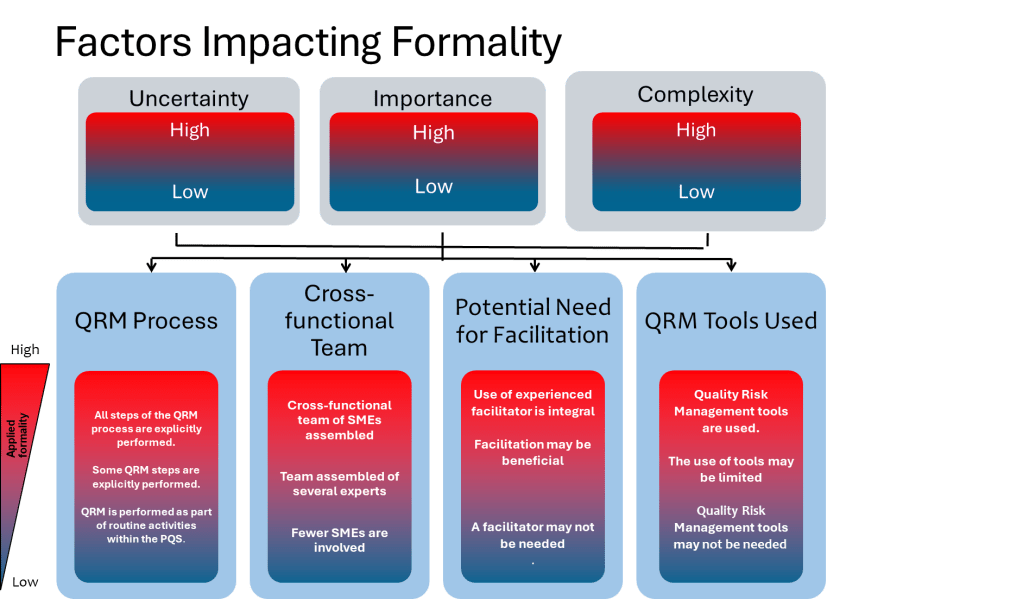

The Formality Framework: When and How to Escalate Bias Management

One of the most valuable aspects of ICH Q9(R1) is its introduction of the formality concept—the idea that different situations require different levels of systematic intervention. Valerie’s article implicitly addresses this by noting that “high formality QRM activities” require trained facilitators. This suggests a graduated approach to bias management that scales intervention intensity with decision importance.

This formality framework needs to include bias management that organizations can use to determine when and how intensively to apply bias mitigation strategies:

- Low Formality Situations: Routine decisions with well-understood parameters, limited stakeholders, and reversible outcomes. Basic bias awareness training and standardized checklists may be sufficient.

- Medium Formality Situations: Decisions involving moderate complexity, uncertainty, or impact. These require cross-functional input, structured decision tools, and documentation of rationales.

- High Formality Situations: Complex, high-stakes decisions with significant uncertainty, multiple conflicting objectives, or diverse stakeholders. These demand external facilitation, systematic bias checks, and formal documentation of how potential biases were addressed.

This framework acknowledges that the GI Joe fallacy is most dangerous in high-formality situations where the stakes are highest and the cognitive demands greatest. It’s precisely in these contexts that our confidence in our ability to overcome bias through awareness becomes most problematic.

The Cultural Dimension: Creating Environments That Support Bias Recognition

Valerie’s emphasis on fostering humility, encouraging teams to acknowledge that “no one is immune to bias, even the most experienced professionals” connects to my observations about building expertise in quality organizations. Creating cultures that can effectively manage subjectivity requires more than tools and processes; it requires psychological safety that allows bias recognition without professional threat.

I’ve noted in past posts that organizations advancing beyond basic awareness levels demonstrate “systematic recognition of cognitive bias risks” with growing understanding that “human judgment limitations can affect risk assessment quality.” However, the transition from awareness to systematic application requires cultural changes that make bias discussion routine rather than threatening.

This cultural dimension becomes particularly important when we consider the ironic processing effects that Valerie references. When organizations create environments where acknowledging bias is seen as admitting incompetence, they inadvertently increase bias through suppression attempts. Teams that must appear confident and decisive may unconsciously avoid bias recognition because it threatens their professional identity.

The solution is creating cultures that frame bias recognition as professional competence rather than limitation. Just as we expect quality professionals to understand statistical process control or regulatory requirements, we should expect them to understand and systematically address their cognitive limitations.

Practical Implementation: Moving Beyond the GI Joe Fallacy

Building on Valerie’s recommendations for structured tools and systematic approaches, here are some specific implementation strategies that organizations can adopt to move beyond bias awareness toward bias management:

- Bias Pre-mortems: Before conducting risk assessments, teams explicitly discuss what biases might affect their analysis and establish specific countermeasures. This makes bias consideration routine rather than reactive.

- Devil’s Advocate Protocols: Systematic assignment of team members to challenge prevailing assumptions and identify information that contradicts emerging conclusions.

- Perspective-Taking Requirements: Formal requirements to consider how different stakeholders (patients, regulators, operators) might view risks differently from the assessment team.

- Bias Audit Trails: Documentation requirements that capture not just what decisions were made, but how potential biases were recognized and addressed during the decision-making process.

- External Review Requirements: For high-formality decisions, mandatory review by individuals who weren’t involved in the initial assessment and can provide fresh perspectives.

These interventions acknowledge that bias management is not about eliminating human judgment—it’s about scaffolding human judgment with systematic processes that compensate for known cognitive limitations.

The Broader Implications: Subjectivity as Systemic Challenge

Valerie’s analysis of the GI Joe Bias connects to broader themes in my work about the effectiveness paradox and the challenges of building rigorous quality systems in an age of pop psychology. The pharmaceutical industry’s tendency to adopt appealing frameworks without rigorous evaluation extends to bias management strategies. Organizations may implement “bias training” or “awareness programs” that create the illusion of progress while failing to address the systematic changes needed for genuine improvement.

The GI Joe Bias serves as a perfect example of this challenge. It’s tempting to believe that naming the bias—recognizing that awareness isn’t enough—somehow protects us from falling into the awareness trap. But the bias is self-referential: knowing about the GI Joe Bias doesn’t automatically prevent us from succumbing to it when implementing bias management strategies.

This is why Valerie’s emphasis on systematic interventions rather than individual awareness is so crucial. Effective bias management requires changing the decision-making environment, not just the decision-makers’ knowledge. It requires building systems, not slogans.

A Call for Systematic Excellence in Bias Management

Valerie’s exploration of the GI Joe Bias provides a crucial call for advancing pharmaceutical quality management beyond the illusion that awareness equals capability. Her work, combined with ICH Q9(R1)’s explicit recognition of subjectivity challenges, creates an opportunity for the industry to develop more sophisticated approaches to cognitive bias management.

The path forward requires acknowledging that bias management is a core competency for quality professionals, equivalent to understanding analytical method validation or process characterization. It requires systematic approaches that scaffold human judgment rather than attempting to eliminate it. Most importantly, it requires cultures that view bias recognition as professional strength rather than weakness.

As I continue to build frameworks for reducing subjectivity in quality risk management and developing structured approaches to decision-making, Valerie’s insights about the limitations of awareness provide essential grounding. The GI Joe Bias reminds us that knowing is not half the battle—it’s barely the beginning.

The real battle lies in creating pharmaceutical quality systems that systematically compensate for human cognitive limitations while leveraging human expertise and judgment. That battle is won not through individual awareness or good intentions, but through systematic excellence in bias management architecture.

What structured approaches has your organization implemented to move beyond bias awareness toward systematic bias management? Share your experiences and challenges as we work together to advance the maturity of risk management practices in our industry.

Meet Valerie Mulholland

Dr. Valerie Mulholland is transforming how our industry thinks about quality risk management. As CEO and Principal Consultant at GMP Services in Ireland, Valerie brings over 25 years of hands-on experience auditing and consulting across biopharmaceutical, pharmaceutical, medical device, and blood transfusion industries throughout the EU, US, and Mexico.

But what truly sets Valerie apart is her unique combination of practical expertise and cutting-edge research. She recently earned her PhD from TU Dublin’s Pharmaceutical Regulatory Science Team, focusing on “Effective Risk-Based Decision Making in Quality Risk Management”. Her groundbreaking research has produced 13 academic papers, with four publications specifically developed to support ICH’s work—research that’s now incorporated into the official ICH Q9(R1) training materials. This isn’t theoretical work gathering dust on academic shelves; it’s research that’s actively shaping global regulatory guidance.

Why Risk Revolution Deserves Your Attention

The Risk Revolution podcast, co-hosted by Valerie alongside Nuala Calnan (25-year pharmaceutical veteran and Arnold F. Graves Scholar) and Dr. Lori Richter (Director of Risk Management at Ultragenyx with 21+ years industry experience), represents something unique in pharmaceutical podcasting. This isn’t your typical regulatory update show—it’s a monthly masterclass in advancing risk management maturity.

In an industry where staying current isn’t optional—it’s essential for patient safety—Risk Revolution offers the kind of continuing education that actually advances your professional capabilities. These aren’t recycled conference presentations; they’re conversations with the people shaping our industry’s future.