People use imprecise words to describe the chance of events all the time — “It’s likely to rain,” or “There’s a real possibility they’ll launch before us,” or “It’s doubtful the nurses will strike.” Not only are such probabilistic terms subjective, but they also can have widely different interpretations. One person’s “pretty likely” is another’s “far from certain.” Our research shows just how broad these gaps in understanding can be and the types of problems that can flow from these differences in interpretation.

Risk estimation is based on two components:

- The probability of the occurrence of harm

- The consequences of that harm

With a third element of detectability of the harm being used in many tools.

Often-times we simplify probability of the occurrence into likelihood. The quoted article above is a good simple primer on why we should be careful of that. It offers three recommendations that I want to talk about. Go read the article and then come back.

I. Use probabilities instead of words to avoid misinterpretation

Avoid the simplified quality probability levels, such as “likely to happen”, “frequent”, “can happen, but not frequently”, “rare”, “remote”, and “unlikely to happen.” Instead determine probability levels. even if you are heavily using expert opinion to drive probabilities, given ranges of numbers such as “<10% of the time”, “20-60% of the time” and “greater than 60% of the time.”

It helps to have several sets of scales.

The article has an awesome graph that really is telling for why we should avoid words.

II. Use structured approaches to set probabilities

Ideally pressure test these using a Delphi approach, or something similar like paired comparisons or absolute probability judgments. Using the historic data, and expert opinion, spend the time to make sure your probabilities actually capture the realities.

Be aware that when using historical data that if there is a very low frequent of occurrence historically, then any estimate of probability will be uncertain. In these cases its important to use predicative techniques and simulations. Monte Carlo anyone?

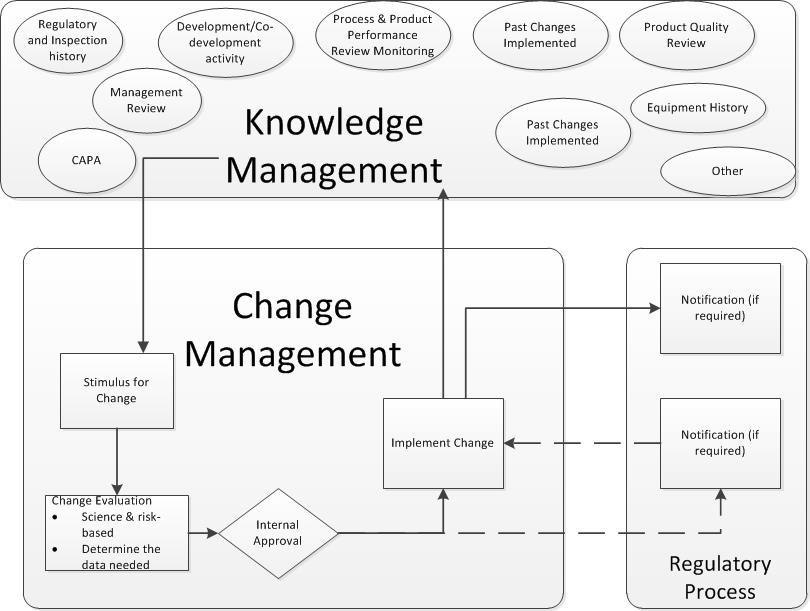

III. Seek feedback to improve your forecasting

Risk management is a lifecycle approach, and you need to be applying good knowledge management to that lifecycle. Have a mechanism to learn from the risk assessments you conduct, and feed that back into your scales. These scales should never be a once and done.

In Conclusion

Risk Management is not new. It’s been around long enough that many companies have the elements in place. What we need to be doing to driving to consistency. Drive out the vague and build best practices that will give the best results. When it comes to likelihood there is a wide body of research on the subject and we should be drawing from it as we work to improve our risk management.

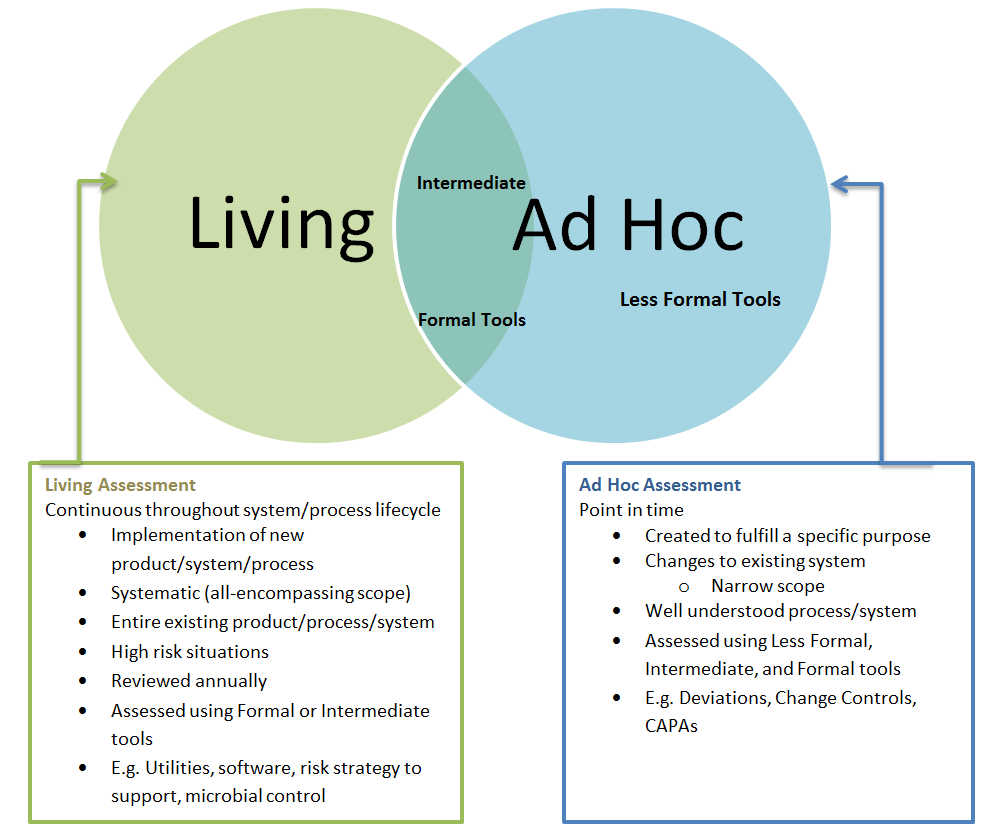

Move beyond setting your scales at the beginning of a risk assessment. Scales should exist as a library (living) that are drawn upon for specific risk evaluations. This will help to ensure that all participants in the risk assessment have a working vocabulary of the criteria, and will keep us honest and prevent any intentional or unintentional manipulation of the criteria based on an expected outcome.

.