In a previous post, I discussed how overcoming subjectivity in risk management and decision-making requires fostering a culture of quality and excellence. This is an issue that it is important to continue to evaluate and push for additional improvement.

The revised ICH Q9(R1) guideline, finalized in January 2023, introduces critical updates to Quality Risk Management (QRM) practices, emphasizing the need to address subjectivity, enhance formality, improve risk-based decision-making, and manage product availability risks. These revisions aim to ensure that QRM processes are more science-driven, knowledge-based, and effective in safeguarding product quality and patient safety. Two years later it is important to continue to build on key strategies for reducing subjectivity in QRM and aligning with the updated requirements.

Understanding Subjectivity in QRM

Subjectivity in QRM arises from personal opinions, biases, heuristics, or inconsistent interpretations of risks by stakeholders. This can impact every stage of the QRM process—from hazard identification to risk evaluation and mitigation. The revised ICH Q9(R1) explicitly addresses this issue by introducing a new subsection, “Managing and Minimizing Subjectivity,” which emphasizes that while subjectivity cannot be entirely eliminated, it can be controlled through structured approaches.

The guideline highlights that subjectivity often stems from poorly designed scoring systems, differing perceptions of hazards and risks among stakeholders, and cognitive biases. To mitigate these challenges, organizations must adopt robust strategies that prioritize scientific knowledge and data-driven decision-making.

Strategies to Reduce Subjectivity

Leveraging Knowledge Management

ICH Q9(R1) underscores the importance of knowledge management as a tool to reduce uncertainty and subjectivity in risk assessments. Effective knowledge management involves systematically capturing, organizing, and applying internal and external knowledge to inform QRM activities. This includes maintaining centralized repositories for technical data, fostering real-time information sharing across teams, and learning from past experiences through structured lessons-learned processes.

By integrating knowledge management into QRM, organizations can ensure that decisions are based on comprehensive data rather than subjective estimations. For example, using historical data on process performance or supplier reliability can provide objective insights into potential risks.

To integrate knowledge management (KM) more effectively into quality risk management (QRM), organizations can implement several strategies to ensure decisions are based on comprehensive data rather than subjective estimations:

Establish Robust Knowledge Repositories

Create centralized, easily accessible repositories for storing and organizing historical data, lessons learned, and best practices. These repositories should include:

- Process performance data

- Supplier reliability metrics

- Deviation and CAPA records

- Audit findings and inspection observations

- Technology transfer documentation

By maintaining these repositories, organizations can quickly access relevant historical information when conducting risk assessments.

Implement Knowledge Mapping

Conduct knowledge mapping exercises to identify key sources of knowledge within the organization. This process helps to:

- Locate subject matter experts

- Identify critical knowledge assets

- Uncover knowledge gaps that may impact risk assessments

Use the resulting knowledge maps to guide risk assessment teams to relevant information and expertise.

Develop Data Analytics Capabilities

Invest in data analytics tools and capabilities to extract meaningful insights from historical data. For example:

- Use statistical process control to identify trends in manufacturing performance

- Apply machine learning algorithms to predict potential quality issues based on historical patterns

- Utilize data visualization tools to present complex risk data in an easily understandable format

These analytics can provide objective, data-driven insights into potential risks and their likelihood of occurrence.

Integrate KM into QRM Processes

Embed KM activities directly into QRM processes to ensure consistent use of available knowledge:

- Include a knowledge gathering step at the beginning of risk assessments

- Require risk assessment teams to document the sources of knowledge used in their analysis

- Implement a formal process for capturing new knowledge generated during risk assessments

This integration helps ensure that all relevant knowledge is considered and that new insights are captured for future use.

Foster a Knowledge-Sharing Culture

Encourage a culture of knowledge sharing and collaboration within the organization:

- Implement mentoring programs to facilitate the transfer of tacit knowledge

- Establish communities of practice around key risk areas

- Recognize and reward employees who contribute valuable knowledge to risk management efforts

By promoting knowledge sharing, organizations can tap into the collective expertise of their workforce to improve risk assessments.

Implementing Structured Risk-Based Decision-Making

The revised guideline introduces a dedicated section on risk-based decision-making, emphasizing the need for structured approaches that consider the complexity, uncertainty, and importance of decisions. Organizations should establish clear criteria for decision-making processes, define acceptable risk tolerance levels, and use evidence-based methods to evaluate options.

Structured decision-making tools can help standardize how risks are assessed and prioritized. Additionally, calibrating expert opinions through formal elicitation techniques can further reduce variability in judgments.

Addressing Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases—such as overconfidence or anchoring—can distort risk assessments and lead to inconsistent outcomes. To address this, organizations should provide training on recognizing common biases and their impact on decision-making. Encouraging diverse perspectives within risk assessment teams can also help counteract individual biases.

For example, using cross-functional teams ensures that different viewpoints are considered when evaluating risks, leading to more balanced assessments. Regularly reviewing risk assessment outputs for signs of bias or inconsistencies can further enhance objectivity.

Enhancing Formality in QRM

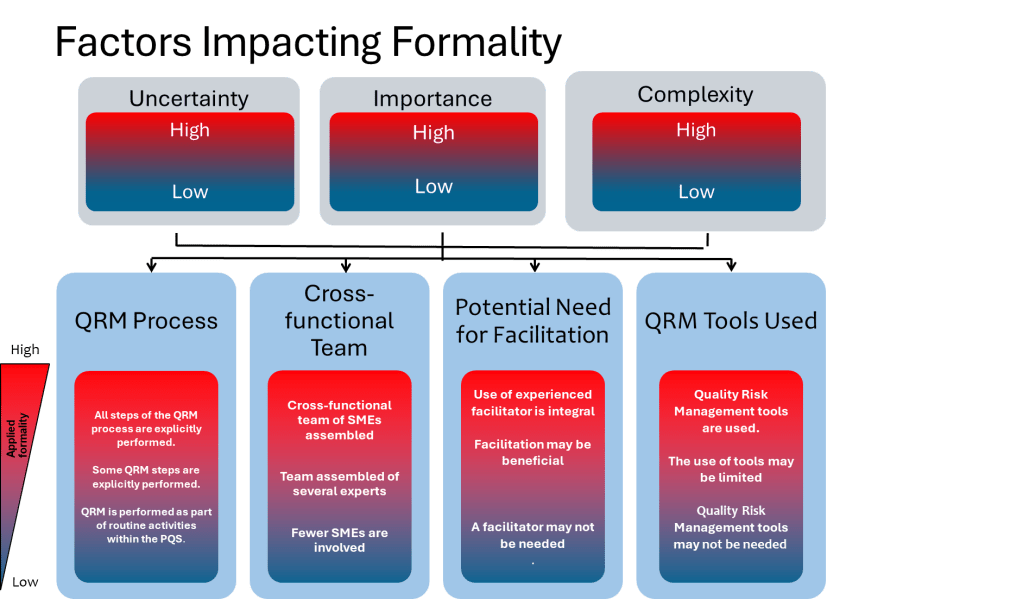

ICH Q9(R1) introduces the concept of a “formality continuum,” which aligns the level of effort and documentation with the complexity and significance of the risk being managed. This approach allows organizations to allocate resources effectively by applying less formal methods to lower-risk issues while reserving rigorous processes for high-risk scenarios.

For instance, routine quality checks may require minimal documentation compared to a comprehensive risk assessment for introducing new manufacturing technologies. By tailoring formality levels appropriately, organizations can ensure consistency while avoiding unnecessary complexity.

Calibrating Expert Opinions

We need to recognize the importance of expert knowledge in QRM activities, but also acknowledges the potential for subjectivity and bias in expert judgments. We need to ensure we:

- Implement formal processes for expert opinion elicitation

- Use techniques to calibrate expert judgments, especially when estimating probabilities

- Provide training on common cognitive biases and their impact on risk assessment

- Employ diverse teams to counteract individual biases

- Regularly review risk assessment outputs for signs of bias or inconsistencies

Calibration techniques may include:

- Structured elicitation protocols that break down complex judgments into more manageable components

- Feedback and training to help experts align their subjective probability estimates with actual frequencies of events

- Using multiple experts and aggregating their judgments through methods like Cooke’s classical model

- Employing facilitation techniques to mitigate groupthink and encourage independent thinking

By calibrating expert opinions, organizations can leverage valuable expertise while minimizing subjectivity in risk assessments.

Utilizing Cooke’s Classical Model

Cooke’s Classical Model is a rigorous method for evaluating and combining expert judgments to quantify uncertainty. Here are the key steps for using the Classical Model to evaluate expert judgment:

Select and calibrate experts:

- Choose 5-10 experts in the relevant field

- Have experts assess uncertain quantities (“calibration questions”) for which true values are known or will be known soon

- These calibration questions should be from the experts’ domain of expertise

Elicit expert assessments:

- Have experts provide probabilistic assessments (usually 5%, 50%, and 95% quantiles) for both calibration questions and questions of interest

- Document experts’ reasoning and rationales

Score expert performance:

- Evaluate experts on two measures:

a) Statistical accuracy: How well their probabilistic assessments match the true values of calibration questions

b) Informativeness: How precise and focused their uncertainty ranges are

Calculate performance-based weights:

- Derive weights for each expert based on their statistical accuracy and informativeness scores

- Experts performing poorly on calibration questions receive little or no weight

Combine expert assessments:

- Use the performance-based weights to aggregate experts’ judgments on the questions of interest

- This creates a “Decision Maker” combining the experts’ assessments

Validate the combined assessment:

- Evaluate the performance of the weighted combination (“Decision Maker”) using the same scoring as for individual experts

- Compare to equal-weight combination and best-performing individual experts

Conduct robustness checks:

- Perform cross-validation by using subsets of calibration questions to form weights

- Assess how well performance on calibration questions predicts performance on questions of interest

The Classical Model aims to create an optimal aggregate assessment that outperforms both equal-weight combinations and individual experts. By using objective performance measures from calibration questions, it provides a scientifically defensible method for evaluating and synthesizing expert judgment under uncertainty.

Using Data to Support Decisions

ICH Q9(R1) emphasizes the importance of basing risk management decisions on scientific knowledge and data. The guideline encourages organizations to:

- Develop robust knowledge management systems to capture and maintain product and process knowledge

- Create standardized repositories for technical data and information

- Implement systems to collect and convert data into usable knowledge

- Gather and analyze relevant data to support risk-based decisions

- Use quantitative methods where feasible, such as statistical models or predictive analytics

Specific approaches for using data in QRM may include:

- Analyzing historical data on process performance, deviations, and quality issues to inform risk assessments

- Employing statistical process control and process capability analysis to evaluate and monitor risks

- Utilizing data mining and machine learning techniques to identify patterns and potential risks in large datasets

- Implementing real-time data monitoring systems to enable proactive risk management

- Conducting formal data quality assessments to ensure decisions are based on reliable information

Digitalization and emerging technologies can support data-driven decision making, but remember that validation requirements for these technologies should not be overlooked.

Improving Risk Assessment Tools

The design of risk assessment tools plays a critical role in minimizing subjectivity. Tools with well-defined scoring criteria and clear guidance on interpreting results can reduce variability in how risks are evaluated. For example, using quantitative methods where feasible—such as statistical models or predictive analytics—can provide more objective insights compared to qualitative scoring systems.

Organizations should also validate their tools periodically to ensure they remain fit-for-purpose and aligned with current regulatory expectations.

Leverage Good Risk Questions

A well-formulated risk question can significantly help reduce subjectivity in quality risk management (QRM) activities. Here’s how a good risk question contributes to reducing subjectivity:

Clarity and Focus

A good risk question provides clarity and focus for the risk assessment process. By clearly defining the scope and context of the risk being evaluated, it helps align all participants on what specifically needs to be assessed. This alignment reduces the potential for individual interpretations and subjective assumptions about the risk scenario.

Specific and Measurable Terms

Effective risk questions use specific and measurable terms rather than vague or ambiguous language. For example, instead of asking “What are the risks to product quality?”, a better question might be “What are the potential causes of out-of-specification dissolution results for Product X in the next 6 months?”. The specificity in the latter question helps anchor the assessment in objective, measurable criteria.

Factual Basis

A well-crafted risk question encourages the use of factual information and data rather than opinions or guesses. It should prompt the risk assessment team to seek out relevant data, historical information, and scientific knowledge to inform their evaluation. This focus on facts and evidence helps minimize the influence of personal biases and subjective judgments.

Standardized Approach

Using a consistent format for risk questions across different assessments promotes a standardized approach to risk identification and analysis. This consistency reduces variability in how risks are framed and evaluated, thereby decreasing the potential for subjective interpretations.

Objective Criteria

Good risk questions often incorporate or imply objective criteria for risk evaluation. For instance, a question like “What factors could lead to a deviation from the acceptable range of 5-10% for impurity Y?” sets clear, objective parameters for the assessment, reducing the room for subjective interpretation of what constitutes a significant risk.

Promotes Structured Thinking

Well-formulated risk questions encourage structured thinking about potential hazards, their causes, and consequences. This structured approach helps assessors focus on objective factors and causal relationships rather than relying on gut feelings or personal opinions.

Facilitates Knowledge Utilization

A good risk question should prompt the assessment team to utilize available knowledge effectively. It encourages the team to draw upon relevant data, past experiences, and scientific understanding, thereby grounding the assessment in objective information rather than subjective impressions.

By crafting risk questions that embody these characteristics, QRM practitioners can significantly reduce the subjectivity in risk assessments, leading to more reliable, consistent, and scientifically sound risk management decisions.

Fostering a Culture of Continuous Improvement

Reducing subjectivity in QRM is an ongoing process that requires a commitment to continuous improvement. Organizations should regularly review their QRM practices to identify areas for enhancement and incorporate feedback from stakeholders. Investing in training programs that build competencies in risk assessment methodologies and decision-making frameworks is essential for sustaining progress.

Moreover, fostering a culture that values transparency, collaboration, and accountability can empower teams to address subjectivity proactively. Encouraging open discussions about uncertainties or disagreements during risk assessments can lead to more robust outcomes.

Conclusion

The revisions introduced in ICH Q9(R1) represent a significant step forward in addressing long-standing challenges associated with subjectivity in QRM. By leveraging knowledge management, implementing structured decision-making processes, addressing cognitive biases, enhancing formality levels appropriately, and improving risk assessment tools, organizations can align their practices with the updated guidelines while ensuring more reliable and science-based outcomes.

It has been two years, it is long past time be be addressing these in your risk management process and quality system.

Ultimately, reducing subjectivity not only strengthens compliance with regulatory expectations but also enhances the quality of pharmaceutical products and safeguards patient safety—a goal that lies at the heart of effective Quality Risk Management.