A Knowledge Accessibility Index (KAI) is a systematic evaluation framework designed to measure how effectively an organization can access and deploy critical knowledge when decision-making requires specialized expertise. Unlike traditional knowledge management metrics that focus on knowledge creation or storage, the KAI specifically evaluates the availability, retrievability, and usability of knowledge at the point of decision-making.

The KAI emerged from recognition that organizational knowledge often becomes trapped in silos or remains inaccessible when most needed, particularly during critical risk assessments or emergency decision-making scenarios. This concept aligns with research showing that knowledge accessibility is a fundamental component of effective knowledge management programs.

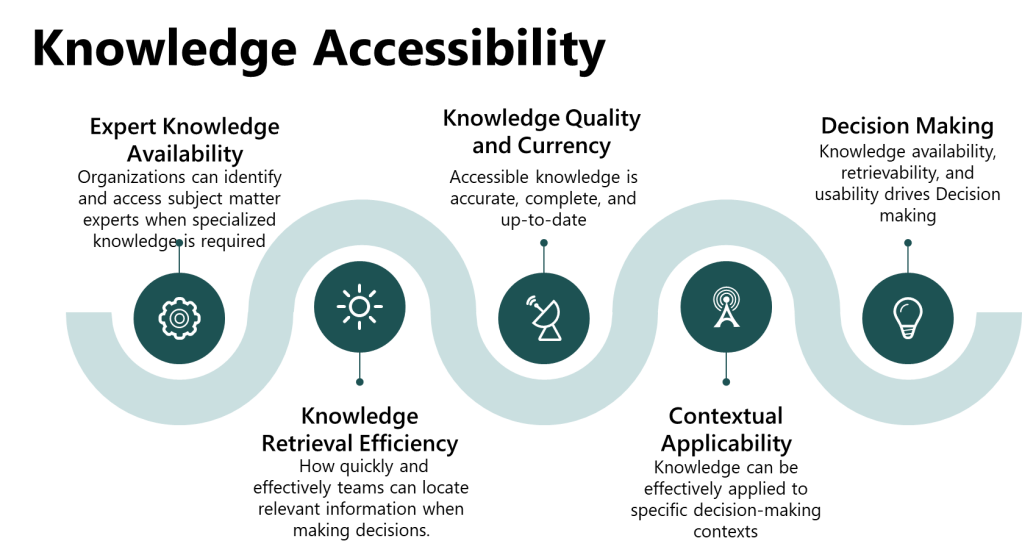

Core Components of Knowledge Accessibility Assessment

A comprehensive KAI framework should evaluate four primary dimensions:

Expert Knowledge Availability

This component assesses whether organizations can identify and access subject matter experts when specialized knowledge is required. Research on knowledge audits emphasizes the importance of expert identification and availability mapping, including:

- Expert mapping and skill matrices that identify knowledge holders and their specific capabilities

- Availability assessment of critical experts during different operational scenarios

- Knowledge succession planning to address risks from expert departure or retirement

- Cross-training coverage to ensure knowledge redundancy for critical capabilities

Knowledge Retrieval Efficiency

This dimension measures how quickly and effectively teams can locate relevant information when making decisions. Knowledge management metrics research identifies time to find information as a critical efficiency indicator, encompassing:

- Search functionality effectiveness within organizational knowledge systems

- Knowledge organization and categorization that supports rapid retrieval

- Information architecture that aligns with decision-making workflows

- Access permissions and security that balance protection with accessibility

Knowledge Quality and Currency

This component evaluates whether accessible knowledge is accurate, complete, and up-to-date. Knowledge audit methodologies emphasize the importance of knowledge validation and quality assessment:

- Information accuracy and reliability verification processes

- Knowledge update frequency and currency management

- Source credibility and validation mechanisms

- Completeness assessment relative to decision-making requirements

Contextual Applicability

This dimension assesses whether knowledge can be effectively applied to specific decision-making contexts. Research on organizational knowledge access highlights the importance of contextual knowledge representation:

- Knowledge contextualization for specific operational scenarios

- Applicability assessment for different decision-making situations

- Integration capabilities with existing processes and workflows

- Usability evaluation from the end-user perspective

Building a Knowledge Accessibility Index: Implementation Framework

Phase 1: Baseline Assessment and Scope Definition

Step 1: Define Assessment Scope

Begin by clearly defining what knowledge domains and decision-making processes the KAI will evaluate. This should align with organizational priorities and critical operational requirements.

- Identify critical decision-making scenarios requiring specialized knowledge

- Map key knowledge domains essential to organizational success

- Determine assessment boundaries and excluded areas

- Establish stakeholder roles and responsibilities for the assessment

Step 2: Conduct Initial Knowledge Inventory

Perform a comprehensive audit of existing knowledge assets and access mechanisms, following established knowledge audit methodologies:

- Document explicit knowledge sources: databases, procedures, technical documentation

- Map tacit knowledge holders: experts, experienced personnel, specialized teams

- Assess current access mechanisms: search systems, expert directories, contact protocols

- Identify knowledge gaps and barriers: missing expertise, access restrictions, system limitations

Phase 2: Measurement Framework Development

Step 3: Define KAI Metrics and Indicators

Develop specific, measurable indicators for each component of knowledge accessibility, drawing from knowledge management KPI research:

Expert Knowledge Availability Metrics:

- Expert response time for knowledge requests

- Coverage ratio (critical knowledge areas with identified experts)

- Expert availability percentage during operational hours

- Knowledge succession risk assessment scores

Knowledge Retrieval Efficiency Metrics:

- Average time to locate relevant information

- Search success rate for knowledge queries

- User satisfaction with knowledge retrieval processes

- System uptime and accessibility percentages

Knowledge Quality and Currency Metrics:

- Information accuracy verification rates

- Knowledge update frequency compliance

- User ratings for knowledge usefulness and reliability

- Error rates in knowledge application

Contextual Applicability Metrics:

- Knowledge utilization rates in decision-making

- Context-specific knowledge completeness scores

- Integration success rates with operational processes

- End-user effectiveness ratings

Step 4: Establish Assessment Methodology

Design systematic approaches for measuring each KAI component, incorporating multiple data collection methods as recommended in knowledge audit literature:

- Quantitative measurements: system analytics, time tracking, usage statistics

- Qualitative assessments: user interviews, expert evaluations, case studies

- Mixed-method approaches: surveys with follow-up interviews, observational studies

- Continuous monitoring: automated metrics collection, periodic reassessment

Phase 3: Implementation and Operationalization

Step 5: Deploy Assessment Tools and Processes

Implement systematic measurement mechanisms following knowledge management assessment best practices:

Technology Infrastructure:

- Knowledge management system analytics and monitoring capabilities

- Expert availability tracking systems

- Search and retrieval performance monitoring tools

- User feedback and rating collection mechanisms

Process Implementation:

- Regular knowledge accessibility audits using standardized protocols

- Expert availability confirmation procedures for critical decisions

- Knowledge quality validation workflows

- User training on knowledge access systems and processes

Step 6: Establish Scoring and Interpretation Framework

Develop a standardized scoring system that enables consistent evaluation and comparison over time, similar to established maturity models:

KAI Scoring Levels:

- Level 1 (Critical Risk): Essential knowledge frequently inaccessible or unavailable

- Level 2 (Moderate Risk): Knowledge accessible but with significant delays or barriers

- Level 3 (Adequate): Generally effective knowledge access with some improvement opportunities

- Level 4 (Good): Reliable and efficient knowledge accessibility for most scenarios

- Level 5 (Excellent): Optimized knowledge accessibility enabling rapid, informed decision-making

Phase 4: Continuous Improvement and Maturity Development

Step 7: Implement Feedback and Improvement Cycles

Establish systematic processes for using KAI results to drive organizational improvements:

- Gap analysis identifying specific areas requiring improvement

- Action planning addressing knowledge accessibility deficiencies

- Progress monitoring tracking improvement implementation effectiveness

- Regular reassessment measuring changes in knowledge accessibility over time

Step 8: Integration with Organizational Processes

Embed KAI assessment and improvement into broader organizational management systems9:

- Strategic planning integration: incorporating knowledge accessibility goals into organizational strategy

- Risk management alignment: using KAI results to inform risk assessment and mitigation planning

- Performance management connection: linking knowledge accessibility to individual and team performance metrics

- Resource allocation guidance: prioritizing investments based on KAI assessment results

Practical Application Examples

For a pharmaceutical manufacturing organization, a KAI might assess:

- Molecule Steward Accessibility: Can the team access a qualified molecule steward within 2 hours for critical quality decisions?

- Technical System Knowledge: Is current system architecture documentation accessible and comprehensible to risk assessment teams?

- Process Owner Availability: Are process owners with recent operational experience available for risk assessment participation?

- Quality Integration Capability: Can quality professionals effectively challenge assumptions and integrate diverse perspectives?

Benefits of Implementing KAI

Improved Decision-Making Quality: By ensuring critical knowledge is accessible when needed, organizations can make more informed, evidence-based decisions.

Risk Mitigation: KAI helps identify knowledge accessibility vulnerabilities before they impact critical operations.

Resource Optimization: Systematic assessment enables targeted improvements in knowledge management infrastructure and processes.

Organizational Resilience: Better knowledge accessibility supports organizational adaptability and continuity during disruptions or personnel changes.

Limitations and Considerations

Implementation Complexity: Developing comprehensive KAI requires significant organizational commitment and resources.

Cultural Factors: Knowledge accessibility often depends on organizational culture and relationships that may be difficult to measure quantitatively.

Dynamic Nature: Knowledge needs and accessibility requirements may change rapidly, requiring frequent reassessment.

Measurement Challenges: Some aspects of knowledge accessibility may be difficult to quantify accurately.

Conclusion

A Knowledge Accessibility Index provides organizations with a systematic framework for evaluating and improving their ability to access critical knowledge when making important decisions. By focusing on expert availability, retrieval efficiency, knowledge quality, and contextual applicability, the KAI addresses a fundamental challenge in knowledge management: ensuring that the right knowledge reaches the right people at the right time.

Successful KAI implementation requires careful planning, systematic measurement, and ongoing commitment to improvement. Organizations that invest in developing robust knowledge accessibility capabilities will be better positioned to make informed decisions, manage risks effectively, and maintain operational excellence in increasingly complex and rapidly changing environments.

The framework presented here provides a foundation for organizations to develop their own KAI systems tailored to their specific operational requirements and strategic objectives. As with any organizational assessment tool, the value of KAI lies not just in measurement, but in the systematic improvements that result from understanding and addressing knowledge accessibility challenges.