The draft Annex 11’s Section 15 Security represents nothing less than the regulatory codification of modern cybersecurity principles into pharmaceutical GMP. Where the 2011 version offered three brief security provisions totaling fewer than 100 words, the 2025 draft delivers 20 comprehensive subsections that read like a cybersecurity playbook designed by paranoid auditors who’ve spent too much time investigating ransomware attacks on manufacturing facilities. As someone with a bit of experience in that, I find the draft fascinating.

Section 15 transforms cybersecurity from a peripheral IT concern into a mandatory foundation of pharmaceutical operations, requiring organizations to implement enterprise-grade security controls. The European regulators have essentially declared that pharmaceutical cybersecurity can no longer be treated as someone else’s problem. Nor can it be treated as something outside of the GMPs.

The Philosophical Transformation: From Trust-Based to Threat-Driven Security

The current Annex 11’s security provisions reflect a fundamentally different era of threat landscape with an approach centering on access restriction and basic audit logging, assuming that physical controls and password authentication provide adequate protection. The language suggests that security controls should be “suitable” and scale with system “criticality,” offering organizations considerable discretion in determining what constitutes appropriate protection.

Section 15 obliterates this discretionary approach by mandating specific, measurable security controls that assume persistent, sophisticated threats as the baseline condition. Rather than suggesting organizations “should” implement firewalls and access controls, the draft requires organizations to deploy network segmentation, disaster recovery capabilities, penetration testing programs, and continuous security improvement processes.

The shift from “suitable methods of preventing unauthorised entry” to requiring “effective information security management systems” represents a fundamental change in regulatory philosophy. The 2011 version treats security breaches as unfortunate accidents to be prevented through reasonable precautions. The 2025 draft treats security breaches as inevitable events requiring comprehensive preparation, detection, response, and recovery capabilities.

Section 15.1 establishes this new paradigm by requiring regulated users to “ensure an effective information security management system is implemented and maintained, which safeguards authorised access to, and detects and prevents unauthorised access to GMP systems and data”. This language transforms cybersecurity from an operational consideration into a regulatory mandate with explicit requirements for ongoing management and continuous improvement.

Quite frankly, I worry that many Quality Units may not be ready for this new level of oversight.

Comparing Section 15 Against ISO 27001: Pharmaceutical-Specific Cybersecurity

The draft Section 15 creates striking alignments with ISO 27001’s Information Security Management System requirements while adding pharmaceutical-specific controls that reflect the unique risks of GMP environments. ISO 27001’s emphasis on risk-based security management, continuous improvement, and comprehensive control frameworks becomes regulatory mandate rather than voluntary best practice.

Physical Security Requirements in Section 15.4 exceed typical ISO 27001 implementations by mandating multi-factor authentication for physical access to server rooms and data centers. Where ISO 27001 Control A.11.1.1 requires “physical security perimeters” and “appropriate entry controls,” Section 15.4 specifically mandates protection against unauthorized access, damage, and loss while requiring secure locking mechanisms for data centers.

The pharmaceutical-specific risk profile drives requirements that extend beyond ISO 27001’s framework. Section 15.5’s disaster recovery provisions require data centers to be “constructed to minimise the risk and impact of natural and manmade disasters” including storms, flooding, earthquakes, fires, power outages, and network failures. This level of infrastructure resilience reflects the critical nature of pharmaceutical manufacturing where system failures can impact patient safety and drug supply chains.

Continuous Security Improvement mandated by Section 15.2 aligns closely with ISO 27001’s Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle while adding pharmaceutical-specific language about staying “updated about new security threats” and implementing measures to “counter this development”. The regulatory requirement transforms ISO 27001’s voluntary continuous improvement into a compliance obligation with potential inspection implications.

The Security Training and Testing requirements in Section 15.3 exceed typical ISO 27001 implementations by mandating “recurrent security awareness training” with effectiveness evaluation through “simulated tests”. This requirement acknowledges that pharmaceutical environments face sophisticated social engineering attacks targeting personnel with access to valuable research data and manufacturing systems.

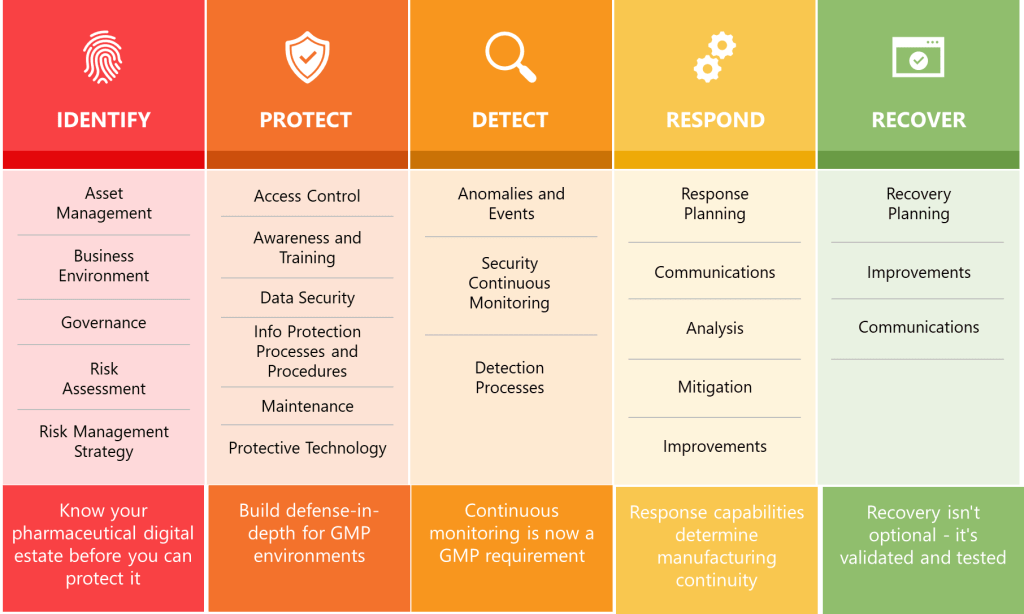

NIST Cybersecurity Framework Convergence: Functions Become Requirements

Section 15’s structure and requirements create remarkable alignment with NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0’s core functions while transforming voluntary guidelines into mandatory pharmaceutical compliance requirements. The NIST CSF’s Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover functions become implicit organizing principles for Section 15’s comprehensive security controls.

Asset Management and Risk Assessment requirements embedded throughout Section 15 align with NIST CSF’s Identify function. Section 15.8’s network segmentation requirements necessitate comprehensive asset inventories and network topology documentation, while Section 15.10’s platform management requirements demand systematic tracking of operating systems, applications, and support lifecycles.

The Protect function manifests through Section 15’s comprehensive defensive requirements including network segmentation, firewall management, access controls, and encryption. Section 15.8 mandates that “networks should be segmented, and effective firewalls implemented to provide barriers between networks, and control incoming and outgoing network traffic”. This requirement transforms NIST CSF’s voluntary protective measures into regulatory obligations with specific technical implementations.

Detection capabilities appear in Section 15.19’s penetration testing requirements, which mandate “regular intervals” of ethical hacking assessments for “critical systems facing the internet”. Section 15.18’s anti-virus requirements extend detection capabilities to endpoint protection with requirements for “continuously updated” virus definitions and “effectiveness monitoring”.

The Respond function emerges through Section 15.7’s disaster recovery planning requirements, which mandate tested disaster recovery plans ensuring “continuity of operation within a defined Recovery Time Objective (RTO)”. Section 15.13’s timely patching requirements create response obligations for addressing “critical vulnerabilities” that “might be immediately” requiring patches.

Recovery capabilities center on Section 15.6’s data replication requirements, which mandate automatic replication of “critical data” from primary to secondary data centers with “delay which is short enough to minimise the risk of loss of data”. The requirement for secondary data centers to be located at “safe distance from the primary site” ensures geographic separation supporting business continuity objectives.

Summary Across Key Guidance Documents

| Security Requirement Area | Draft Annex 11 Section 15 (2025) | Current Annex 11 (2011) | ISO 27001:2022 | NIST CSF 2.0 (2024) | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Security Management System | Mandatory – Effective ISMS implementation and maintenance required (15.1) | Basic – General security measures, no ISMS requirement | Core – ISMS is fundamental framework requirement (Clause 4-10) | Framework – Governance as foundational function across all activities | High – Requires comprehensive ISMS deployment |

| Continuous Security Improvement | Required – Continuous updates on threats and countermeasures (15.2) | Not specified – No continuous improvement mandate | Mandatory – Continual improvement through PDCA cycle (Clause 10.2) | Built-in – Continuous improvement through framework implementation | Medium – Ongoing process establishment needed |

| Security Training & Testing | Mandatory – Recurrent training with simulated testing effectiveness evaluation (15.3) | Not mentioned – No training or testing requirements | Required – Information security awareness and training (A.6.3) | Emphasized – Cybersecurity workforce development and training (GV.WF) | Medium – Training programs and testing infrastructure |

| Physical Security Controls | Explicit – Multi-factor authentication for server rooms, secure data centers (15.4) | Limited – “Suitable methods” for preventing unauthorized entry | Detailed – Physical and environmental security controls (A.11.1-11.2) | Addressed – Physical access controls within Protect function (PR.AC-2) | Medium – Physical infrastructure and access systems |

| Network Segmentation & Firewalls | Mandatory – Network segmentation with strict firewall rules, periodic reviews (15.8-15.9) | Basic – Firewalls mentioned without specific requirements | Specified – Network security management and segmentation (A.13.1) | Core – Network segmentation and boundary protection (PR.AC-5, PR.DS-5) | High – Network architecture redesign often required |

| Platform & Patch Management | Required – Timely OS updates, validation before vendor support expires (15.10-15.14) | Not specified – No explicit platform or patch management | Required – System security and vulnerability management (A.12.6, A.14.2) | Essential – Vulnerability management and patch deployment (ID.RA-1, RS.MI) | High – Complex validation and lifecycle management |

| Disaster Recovery & Business Continuity | Mandatory – Tested disaster recovery with defined RTO requirements (15.7) | Not mentioned – No disaster recovery requirements | Comprehensive – Information systems availability and business continuity (A.17) | Fundamental – Recovery planning and business continuity (RC.RP, RC.CO) | High – Business continuity infrastructure and testing |

| Data Replication & Backup | Required – Automatic critical data replication to geographically separated sites (15.6) | Limited – Basic backup provisions only | Required – Information backup and recovery procedures (A.12.3) | Critical – Data backup and recovery capabilities (PR.IP-4, RC.RP-1) | High – Geographic replication and automated systems |

| Endpoint Security & Device Control | Strict – USB port controls, bidirectional device scanning, default deactivation (15.15-15.17)1 | Not specified – No device control requirements | Detailed – Equipment maintenance and secure disposal (A.11.2, A.11.2.7) | Important – Removable media and device controls (PR.PT-2) | Medium – Device management and scanning systems |

| Anti-virus & Malware Protection | Mandatory – Continuously updated anti-virus with effectiveness monitoring (15.18) | Not mentioned – No anti-virus requirements | Required – Protection against malware (A.12.2) | Standard – Malicious code protection (PR.PT-1) | Low – Standard anti-virus deployment |

| Penetration Testing | Required – Regular ethical hacking for internet-facing critical systems (15.19) | Not specified – No penetration testing requirements | Recommended – Technical vulnerability testing (A.14.2.8) | Recommended – Vulnerability assessments and penetration testing (DE.CM) | Medium – External testing services and internal capabilities |

| Risk-Based Security Assessment | Implicit – Risk-based approach integrated throughout all requirements | General – Risk assessment mentioned but not detailed | Fundamental – Risk management is core methodology (Clause 6.1.2) | Core – Risk assessment and management across all functions (GV.RM, ID.RA) | Medium – Risk assessment processes and documentation |

| Access Control & Authentication | Enhanced – Beyond basic access controls, integrated with physical security | Basic – Password protection and access restriction only | Comprehensive – Access control management framework (A.9) | Comprehensive – Identity management and access controls (PR.AC) | Medium – Enhanced access control systems |

| Incident Response & Management | Implied – Through disaster recovery and continuous improvement requirements | Not specified – No incident response requirements | Required – Information security incident management (A.16) | Detailed – Incident response and recovery processes (RS, RC functions) | Medium – Incident response processes and teams |

| Documentation & Audit Trail | Comprehensive – Detailed documentation for all security controls and testing | Limited – Basic audit trail and documentation | Mandatory – Documented information and records management (Clause 7.5) | Integral – Documentation and communication throughout framework | High – Comprehensive documentation and audit systems |

| Third-Party Risk Management | Implicit – Through platform management and network security requirements | Not mentioned – No third-party risk provisions | Required – Supplier relationships and information security (A.15) | Addressed – Supply chain risk management (ID.SC, GV.SC) | Medium – Supplier assessment and management processes |

| Encryption & Data Protection | Limited – Not explicitly detailed beyond data replication requirements | Not specified – No encryption requirements | Comprehensive – Cryptography and data protection controls (A.10) | Included – Data security and privacy protection (PR.DS) | Medium – Encryption deployment and key management |

| Change Management Integration | Integrated – Security updates must align with GMP validation processes | Basic – Change control mentioned generally | Integrated – Change management throughout ISMS (A.14.2.2) | Embedded – Change management within improvement processes | High – Integration with existing GMP change control |

| Compliance Monitoring | Built-in – Regular reviews, testing, and continuous improvement mandated | Limited – Periodic review mentioned without specifics | Required – Monitoring, measurement, and internal audits (Clause 9) | Systematic – Continuous monitoring and measurement (DE, GV functions) | Medium – Monitoring and measurement systems |

| Executive Oversight & Governance | Implied – Through ISMS requirements and continuous improvement mandates | Not specified – No governance requirements | Mandatory – Leadership commitment and management responsibility (Clause 5) | Essential – Governance and leadership accountability (GV function)4 | Medium – Governance structure and accountability |

The alignment with ISO 27001 and NIST CSF demonstrates that pharmaceutical organizations can no longer treat cybersecurity as a separate concern from GMP compliance—they become integrated regulatory requirements demanding enterprise-grade security capabilities that most pharmaceutical companies have historically considered optional.

Technical Requirements That Challenge Traditional Pharmaceutical IT Architecture

Section 15’s technical requirements will force fundamental changes in how pharmaceutical organizations architect, deploy, and manage their IT infrastructure. The regulatory prescriptions extend far beyond current industry practices and demand enterprise-grade security capabilities that many pharmaceutical companies currently lack.

Network Architecture Revolution begins with Section 15.8’s segmentation requirements, which mandate that “networks should be segmented, and effective firewalls implemented to provide barriers between networks”. This requirement eliminates the flat network architectures common in pharmaceutical manufacturing environments where laboratory instruments, manufacturing equipment, and enterprise systems often share network segments for operational convenience.

The firewall rule requirements demand “IP addresses, destinations, protocols, applications, or ports” to be “defined as strict as practically feasible, only allowing necessary and permissible traffic”. For pharmaceutical organizations accustomed to permissive network policies that allow broad connectivity for troubleshooting and maintenance, this represents a fundamental shift toward zero-trust architecture principles.

Section 15.9’s firewall review requirements acknowledge that “firewall rules tend to be changed or become insufficient over time” and mandate periodic reviews to ensure firewalls “continue to be set as tight as possible”. This requirement transforms firewall management from a deployment activity into an ongoing operational discipline requiring dedicated resources and systematic review processes.

Platform and Patch Management requirements in Sections 15.10 through 15.14 create comprehensive lifecycle management obligations that most pharmaceutical organizations currently handle inconsistently. Section 15.10 requires operating systems and platforms to be “updated in a timely manner according to vendor recommendations, to prevent their use in an unsupported state”.

The validation and migration requirements in Section 15.11 create tension between security imperatives and GMP validation requirements. Organizations must “plan and complete” validation of applications on updated platforms “in due time prior to the expiry of the vendor’s support”. This requirement demands coordination between IT security, quality assurance, and validation teams to ensure system updates don’t compromise GMP compliance.

Section 15.12’s isolation requirements for unsupported platforms acknowledge the reality that pharmaceutical organizations often operate legacy systems that cannot be easily updated. The requirement that such systems “should be isolated from computer networks and the internet” creates network architecture challenges where isolated systems must still support critical manufacturing processes.

Endpoint Security and Device Management requirements in Sections 15.15 through 15.18 address the proliferation of connected devices in pharmaceutical environments. Section 15.15’s “strict control” of bidirectional devices like USB drives acknowledges that pharmaceutical manufacturing environments often require portable storage for equipment maintenance and data collection.

The effective scanning requirements in Section 15.16 for devices that “may have been used outside the organisation” create operational challenges for service technicians and contractors who need to connect external devices to pharmaceutical systems. Organizations must implement scanning capabilities that can “effectively” detect malware without disrupting operational workflows.

Section 15.17’s requirements to deactivate USB ports “by default” unless needed for essential devices like keyboards and mice will require systematic review of all computer systems in pharmaceutical facilities. Manufacturing computers, laboratory instruments, and quality control systems that currently rely on USB connectivity for routine operations may require architectural changes or enhanced security controls.

Operational Impact: How Section 15 Changes Day-to-Day Operations

The implementation of Section 15’s security requirements will fundamentally change how pharmaceutical organizations conduct routine operations, from equipment maintenance to data management to personnel access. These changes extend far beyond IT departments to impact every function that interacts with computerized systems.

Manufacturing and Laboratory Operations will experience significant changes through network segmentation and access control requirements. Section 15.8’s segmentation requirements may isolate manufacturing systems from corporate networks, requiring new procedures for accessing data, transferring files, and conducting remote troubleshooting1. Equipment vendors who previously connected remotely to manufacturing systems for maintenance may need to adapt to more restrictive access controls and monitored connections.

The USB control requirements in Sections 15.15-15.17 will particularly impact operations where portable storage devices are routinely used for data collection, equipment calibration, and maintenance activities. Laboratory personnel accustomed to using USB drives for transferring analytical data may need to adopt network-based file transfer systems or enhanced scanning procedures.

Information Technology Operations must expand significantly to support Section 15’s comprehensive requirements. The continuous security improvement mandate in Section 15.2 requires dedicated resources for threat intelligence monitoring, security tool evaluation, and control implementation. Organizations that currently treat cybersecurity as a periodic concern will need to establish ongoing security operations capabilities.

Section 15.19’s penetration testing requirements for “critical systems facing the internet” will require organizations to either develop internal ethical hacking capabilities or establish relationships with external security testing providers. The requirement for “regular intervals” suggests ongoing testing programs rather than one-time assessments.

The firewall review requirements in Section 15.9 necessitate systematic processes for evaluating and updating network security rules. Organizations must establish procedures for documenting firewall changes, reviewing rule effectiveness, and ensuring rules remain “as tight as possible” while supporting legitimate business functions.

Quality Unit functions must expand to encompass cybersecurity validation and documentation requirements. Section 15.11’s requirements to validate applications on updated platforms before vendor support expires will require QA involvement in IT infrastructure changes. Quality systems must incorporate procedures for evaluating the GMP impact of security patches, platform updates, and network changes.

The business continuity requirements in Section 15.7 necessitate testing of disaster recovery plans and validation that systems can meet “defined Recovery Time Objectives”. Quality assurance must develop capabilities for validating disaster recovery processes and documenting that backup systems can support GMP operations during extended outages.

Strategic Implications: Organizational Structure and Budget Priorities

Section 15’s comprehensive security requirements will force pharmaceutical organizations to reconsider their IT governance structures, budget allocations, and strategic priorities. The regulatory mandate for enterprise-grade cybersecurity capabilities creates organizational challenges that extend beyond technical implementation.

IT-OT Convergence Acceleration becomes inevitable as Section 15’s requirements apply equally to traditional IT systems and operational technology supporting manufacturing processes. Organizations must develop unified security approaches spanning enterprise networks, manufacturing systems, and laboratory instruments. The traditional separation between corporate IT and manufacturing systems operations becomes unsustainable when both domains require coordinated security management.

The network segmentation requirements in Section 15.8 demand comprehensive understanding of all connected systems and their communication requirements. Organizations must develop capabilities for mapping and securing complex environments where ERP systems, manufacturing execution systems, laboratory instruments, and quality management applications share network infrastructure.

Cybersecurity Organizational Evolution will likely drive consolidation of security responsibilities under dedicated chief information security officer roles with expanded authority over both IT and operational technology domains. The continuous improvement mandates and comprehensive technical requirements demand specialized cybersecurity expertise that extends beyond traditional IT administration.

Section 15.3’s training and testing requirements necessitate systematic cybersecurity awareness programs with “effectiveness evaluation” through simulated attacks1. Organizations must develop internal capabilities for conducting phishing simulations, security training programs, and measuring personnel security behaviors.

Budget and Resource Reallocation becomes necessary to support Section 15’s comprehensive requirements. The penetration testing, platform management, network segmentation, and disaster recovery requirements represent significant ongoing operational expenses that many pharmaceutical organizations have not historically prioritized.

The validation requirements for security updates in Section 15.11 create ongoing costs for qualifying platform changes and validating application compatibility. Organizations must budget for accelerated validation cycles to ensure security updates don’t result in unsupported systems.

Inspection and Enforcement: The New Reality

Section 15’s detailed technical requirements create specific inspection targets that regulatory authorities can evaluate objectively during facility inspections. Unlike the current Annex 11’s general security provisions, Section 15’s prescriptive requirements enable inspectors to assess compliance through concrete evidence and documentation.

Technical Evidence Requirements emerge from Section 15’s specific mandates for firewalls, network segmentation, patch management, and penetration testing. Inspectors can evaluate firewall configurations, review network topology documentation, assess patch deployment records, and verify penetration testing reports. Organizations must maintain detailed documentation demonstrating compliance with each technical requirement.

The continuous improvement mandate in Section 15.2 creates expectations for ongoing security enhancement activities with documented evidence of threat monitoring and control implementation. Inspectors will expect to see systematic processes for identifying emerging threats and implementing appropriate countermeasures.

Operational Process Validation requirements extend to security operations including incident response, access control management, and backup testing. Section 15.7’s disaster recovery testing requirements create inspection opportunities for validating recovery procedures and verifying RTO achievement1. Organizations must demonstrate that their business continuity plans work effectively through documented testing activities.

The training and testing requirements in Section 15.3 create audit trails for security awareness programs and simulated attack exercises. Inspectors can evaluate training effectiveness through documentation of phishing simulation results, security incident responses, and personnel security behaviors.

Industry Transformation: From Compliance to Competitive Advantage

Organizations that excel at implementing Section 15’s requirements will gain significant competitive advantages through superior operational resilience, reduced cyber risk exposure, and enhanced regulatory relationships. The comprehensive security requirements create opportunities for differentiation through demonstrated cybersecurity maturity.

Supply Chain Security Leadership emerges as pharmaceutical companies with robust cybersecurity capabilities become preferred partners for collaborations, clinical trials, and manufacturing agreements. Section 15’s requirements create third-party evaluation criteria that customers and partners can use to assess supplier cybersecurity capabilities.

The disaster recovery and business continuity requirements in Sections 15.6 and 15.7 create operational resilience that supports supply chain reliability. Organizations that can demonstrate rapid recovery from cyber incidents maintain competitive advantages in markets where supply chain disruptions have significant patient impact.

Regulatory Efficiency Benefits accrue to organizations that proactively implement Section 15’s requirements before they become mandatory. Early implementation demonstrates regulatory leadership and may result in more efficient inspection processes and enhanced regulatory relationships.

The systematic approach to cybersecurity documentation and process validation creates operational efficiencies that extend beyond compliance. Organizations that implement comprehensive cybersecurity management systems often discover improvements in change control, incident response, and operational monitoring capabilities.

Section 15 Security ultimately represents the transformation of pharmaceutical cybersecurity from optional IT initiative to mandatory operational capability that is part of the pharmaceutical quality system. The pharmaceutical industry’s digital future depends on treating cybersecurity as seriously as traditional quality assurance—and Section 15 makes that treatment legally mandatory.