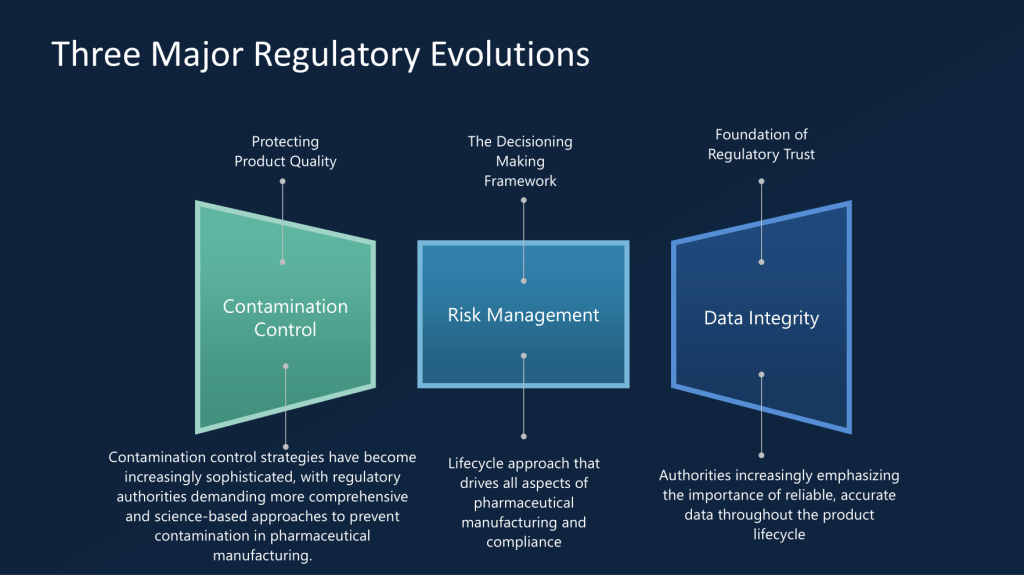

If there is one section that serves as the philosophical and operational backbone for everything else in the new regulation, it’s Section 4: Risk Management. This section embodies current regulatory thinking on how risk management, in light of the recent ICH Q9 (R1) is the scientific methodology that transforms how we think about, design, validate, and operate s in GMP environments.

Section 4 represents the regulatory codification of what quality professionals have long advocated: that every decision about computerized systems, from initial selection through operational oversight to eventual decommissioning, must be grounded in rigorous, documented, and scientifically defensible risk assessment. But more than that, it establishes quality risk management as the living nervous system of digital compliance, continuously sensing, evaluating, and responding to threats and opportunities throughout the system lifecycle.

For organizations that have treated risk management as a checkbox exercise or a justification for doing less validation, Section 4 delivers a harsh wake-up call. The new requirements don’t just elevate risk management to regulatory mandate—they transform it into the primary lens through which all computerized system activities must be viewed, planned, executed, and continuously improved.

The Philosophical Revolution: From Optional Framework to Mandatory Foundation

The transformation between the current Annex 11’s brief mention of risk management and Section 4’s comprehensive requirements represents more than regulatory updating—it reflects a fundamental shift in how regulators view the relationship between risk assessment and system control. Where the 2011 version offered generic guidance about applying risk management “throughout the lifecycle,” Section 4 establishes specific, measurable, and auditable requirements that make risk management the definitive basis for all computerized system decisions.

Section 4.1 opens with an unambiguous statement that positions quality risk management as the foundation of system lifecycle management: “Quality Risk Management (QRM) should be applied throughout the lifecycle of a computerised system considering any possible impact on product quality, patient safety or data integrity.” This language moves beyond the permissive “should consider” of the old regulation to establish QRM as the mandatory framework through which all system activities must be filtered.

The explicit connection to ICH Q9(R1) in Section 4.2 represents a crucial evolution. By requiring that “risks associated with the use of computerised systems in GMP activities should be identified and analysed according to an established procedure” and specifically referencing “examples of risk management methods and tools can be found in ICH Q9 (R1),” the regulation transforms ICH Q9 from guidance into regulatory requirement. Organizations can no longer treat ICH Q9 principles as aspirational best practices—they become the enforceable standard for pharmaceutical risk management.

This integration creates powerful synergies between pharmaceutical quality system requirements and computerized system validation. Risk assessments conducted under Section 4 must align with broader ICH Q9 principles while addressing the specific challenges of digital systems, cloud services, and automated processes. The result is a comprehensive risk management framework that bridges traditional pharmaceutical operations with modern digital infrastructure.

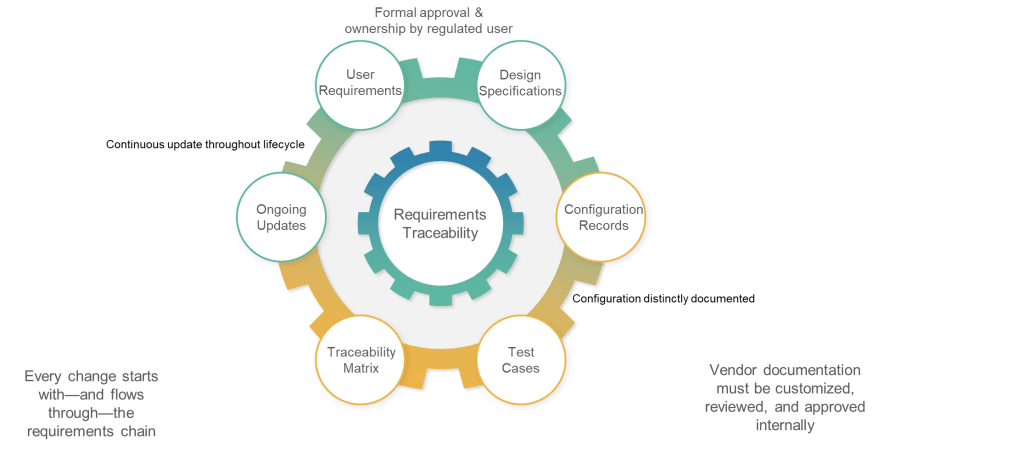

The requirement in Section 4.3 that “validation strategy and effort should be determined based on the intended use of the system and potential risks to product quality, patient safety and data integrity” establishes risk assessment as the definitive driver of validation scope and approach. This eliminates the historical practice of using standardized validation templates regardless of system characteristics or applying uniform validation approaches across diverse system types.

Under Section 4, every validation decision—from the depth of testing required to the frequency of periodic reviews—must be traceable to specific risk assessments that consider the unique characteristics of each system and its role in GMP operations. This approach rewards organizations that invest in comprehensive risk assessment while penalizing those that rely on generic, one-size-fits-all validation approaches.

Risk-Based System Design: Architecture Driven by Assessment

Perhaps the most transformative aspect of Section 4 is found in Section 4.4, which requires that “risks associated with the use of computerised systems in GMP activities should be mitigated and brought down to an acceptable level, if possible, by modifying processes or system design.” This requirement positions risk assessment as a primary driver of system architecture rather than simply a validation planning tool.

The language “modifying processes or system design” establishes a hierarchy of risk control that prioritizes prevention over detection. Rather than accepting inherent system risks and compensating through enhanced testing or operational controls, Section 4 requires organizations to redesign systems and processes to eliminate or minimize risks at their source. This approach aligns with fundamental safety engineering principles while ensuring that risk mitigation is built into system architecture rather than layered on top.

The requirement that “the outcome of the risk management process should result in the choice of an appropriate computerised system architecture and functionality” makes risk assessment the primary criterion for system selection and configuration. Organizations can no longer choose systems based purely on cost, vendor relationships, or technical preferences—they must demonstrate that system architecture aligns with risk assessment outcomes and provides appropriate risk mitigation capabilities.

This approach particularly impacts cloud system implementations, SaaS platform selections, and integrated system architectures where risk assessment must consider not only individual system capabilities but also the risk implications of system interactions, data flows, and shared infrastructure. Organizations must demonstrate that their chosen architecture provides adequate risk control across the entire integrated environment.

The emphasis on system design modification as the preferred risk mitigation approach will drive significant changes in vendor selection criteria and system specification processes. Vendors that can demonstrate built-in risk controls and flexible architecture will gain competitive advantages over those that rely on customers to implement risk mitigation through operational procedures or additional validation activities.

Data Integrity Risk Assessment: Scientific Rigor Applied to Information Management

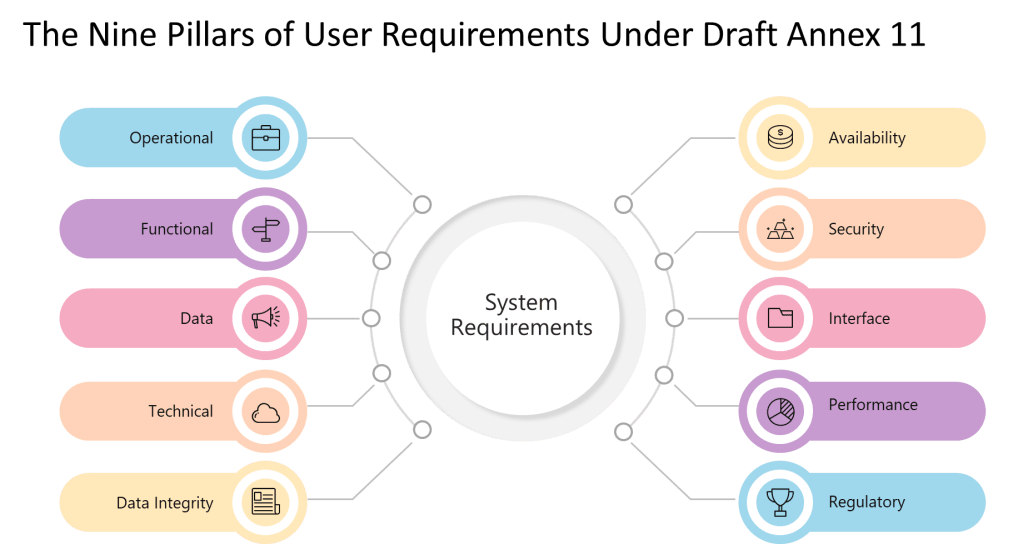

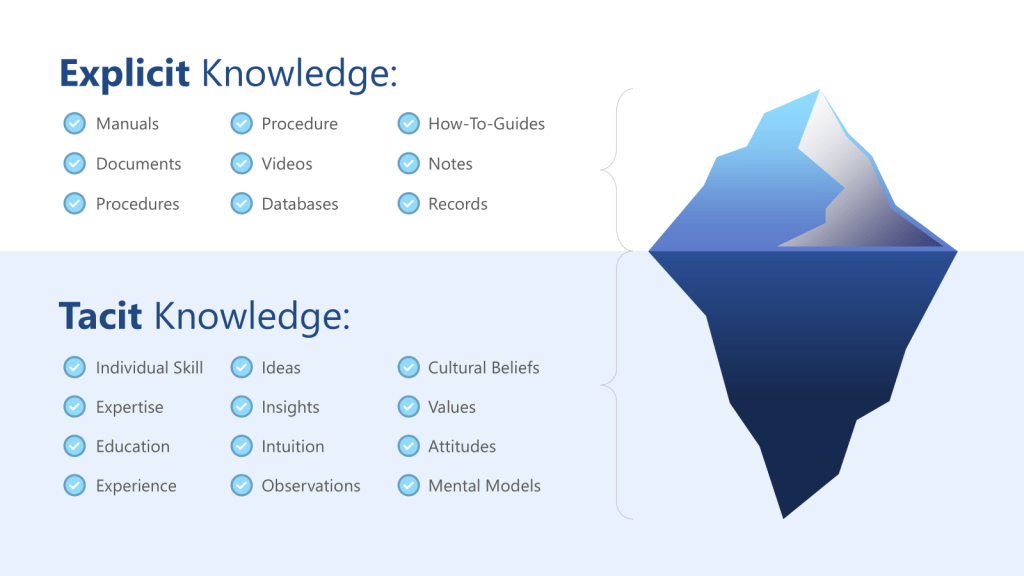

Section 4.5 introduces one of the most sophisticated requirements in the entire draft regulation: “Quality risk management principles should be used to assess the criticality of data to product quality, patient safety and data integrity, the vulnerability of data to deliberate or indeliberate alteration, deletion or loss, and the likelihood of detection of such actions.”

This requirement transforms data integrity from a compliance concept into a systematic risk management discipline. Organizations must assess not only what data is critical but also how vulnerable that data is to compromise and how likely they are to detect integrity failures. This three-dimensional risk assessment approach—criticality, vulnerability, and detectability—provides a scientific framework for prioritizing data protection efforts and designing appropriate controls.

The distinction between “deliberate or indeliberate” data compromise acknowledges that modern data integrity threats encompass both malicious attacks and innocent errors. Risk assessments must consider both categories and design controls that address the full spectrum of potential data integrity failures. This approach requires organizations to move beyond traditional access control and audit trail requirements to consider the full range of technical, procedural, and human factors that could compromise data integrity.

The requirement to assess “likelihood of detection” introduces a crucial element often missing from traditional data integrity approaches. Organizations must evaluate not only how to prevent data integrity failures but also how quickly and reliably they can detect failures that occur despite preventive controls. This assessment drives requirements for monitoring systems, audit trail analysis capabilities, and incident detection procedures that can identify data integrity compromises before they impact product quality or patient safety.

This risk-based approach to data integrity creates direct connections between Section 4 and other draft Annex 11 requirements, particularly Section 10 (Handling of Data), Section 11 (Identity and Access Management), and Section 12 (Audit Trails). Risk assessments conducted under Section 4 drive the specific requirements for data input verification, access controls, and audit trail monitoring implemented through other sections.

Lifecycle Risk Management: Dynamic Assessment in Digital Environments

The lifecycle approach required by Section 4 acknowledges that computerized systems exist in dynamic environments where risks evolve continuously due to technology changes, process modifications, security threats, and operational experience. Unlike traditional validation approaches that treat risk assessment as a one-time activity during system implementation, Section 4 requires ongoing risk evaluation and response throughout the system lifecycle.

This dynamic approach particularly impacts cloud-based systems and SaaS platforms where underlying infrastructure, security controls, and functional capabilities change regularly without direct customer involvement. Organizations must establish procedures for evaluating the risk implications of vendor-initiated changes and updating their risk assessments and control strategies accordingly.

The lifecycle risk management approach also requires integration with change control processes, periodic review activities, and incident management procedures. Every significant system change must trigger risk reassessment to ensure that new risks are identified and appropriate controls are implemented. This creates a feedback loop where operational experience informs risk assessment updates, which in turn drive control system improvements and validation strategy modifications.

Organizations implementing Section 4 requirements must develop capabilities for continuous risk monitoring that can detect emerging threats, changing system characteristics, and evolving operational patterns that might impact risk assessments. This requires investment in risk management tools, monitoring systems, and analytical capabilities that extend beyond traditional validation and quality assurance functions.

Integration with Modern Risk Management Methodologies

The explicit reference to ICH Q9(R1) in Section 4.2 creates direct alignment between computerized system risk management and the broader pharmaceutical quality risk management framework. This integration ensures that computerized system risk assessments contribute to overall product and process risk understanding while benefiting from the sophisticated risk management methodologies developed for pharmaceutical operations.

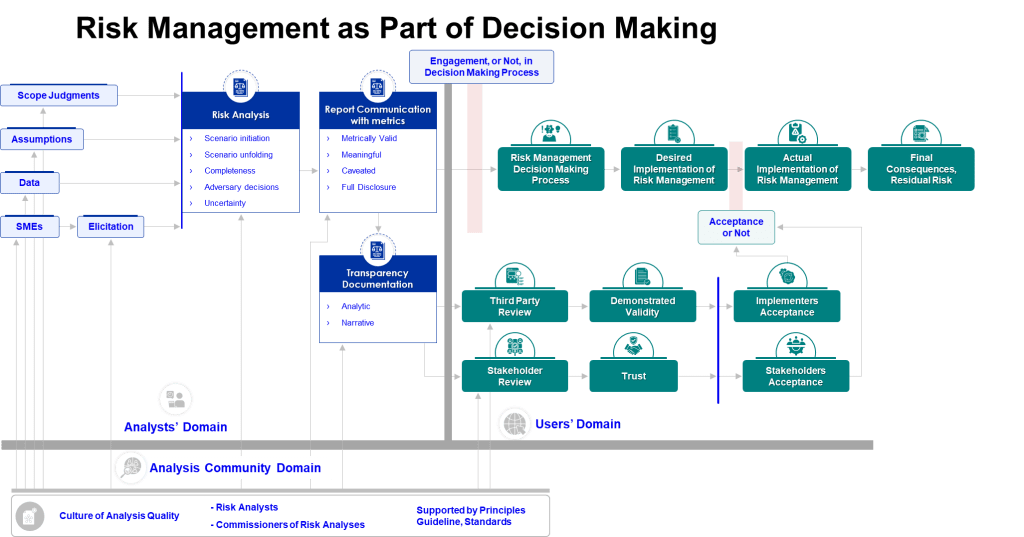

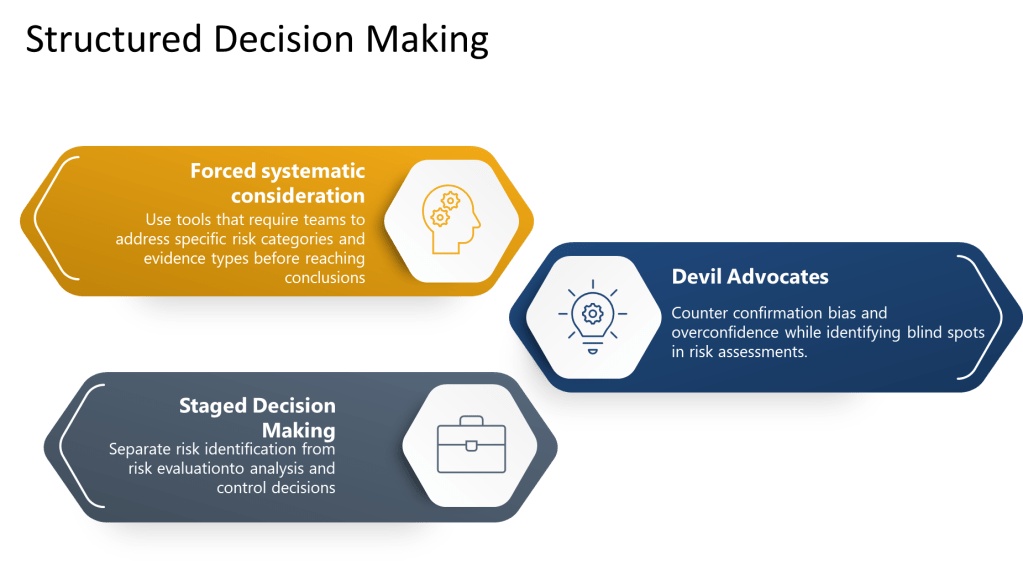

ICH Q9(R1)’s emphasis on managing and minimizing subjectivity in risk assessment becomes particularly important for computerized system applications where technical complexity can obscure risk evaluation. Organizations must implement risk assessment procedures that rely on objective data, established methodologies, and cross-functional expertise rather than individual opinions or vendor assertions.

The ICH Q9(R1) toolkit—including Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), and Fault Tree Analysis (FTA)—provides proven methodologies for systematic risk identification and assessment that can be applied to computerized system environments. Section 4’s reference to these tools establishes them as acceptable approaches for meeting regulatory requirements while providing flexibility for organizations to choose methodologies appropriate to their specific circumstances.

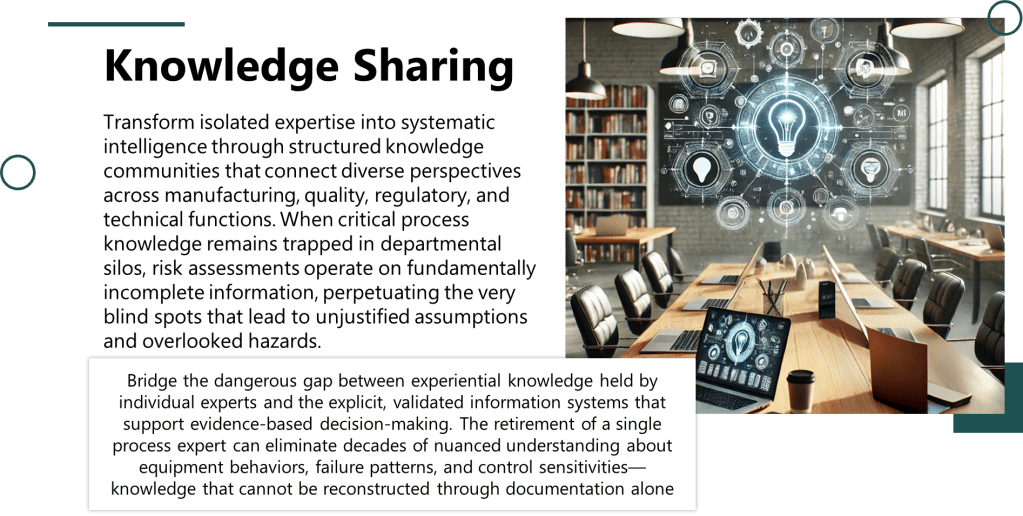

The integration with ICH Q9(R1) also emphasizes the importance of risk communication throughout the organization and with external stakeholders including suppliers, regulators, and business partners. Risk assessment results must be communicated effectively to drive appropriate decision-making at all organizational levels and ensure that risk mitigation strategies are understood and implemented consistently.

Operational Implementation: Transforming Risk Assessment from Theory to Practice

Implementing Section 4 requirements effectively requires organizations to develop sophisticated risk management capabilities that extend far beyond traditional validation and quality assurance functions. The requirement for “established procedures” means that risk assessment cannot be ad hoc or inconsistent—organizations must develop repeatable, documented methodologies that produce reliable and auditable results.

The procedures must address risk identification methods that can systematically evaluate the full range of potential threats to computerized systems including technical failures, security breaches, data integrity compromises, supplier issues, and operational errors. Risk identification must consider both current system states and future scenarios including planned changes, emerging threats, and evolving operational requirements.

Risk analysis procedures must provide quantitative or semi-quantitative methods for evaluating risk likelihood and impact across the three critical dimensions specified in Section 4.1: product quality, patient safety, and data integrity. This analysis must consider the interconnected nature of modern computerized systems where risks in one system or component can cascade through integrated environments to impact multiple processes and outcomes.

Risk evaluation procedures must establish criteria for determining acceptable risk levels and identifying risks that require mitigation. These criteria must align with organizational risk tolerance, regulatory expectations, and business objectives while providing clear guidance for risk-based decision making throughout the system lifecycle.

Risk mitigation procedures must prioritize design and process modifications over operational controls while ensuring that all risk mitigation strategies are evaluated for effectiveness and maintained throughout the system lifecycle. Organizations must develop capabilities for implementing system architecture changes, process redesign, and operational control enhancements based on risk assessment outcomes.

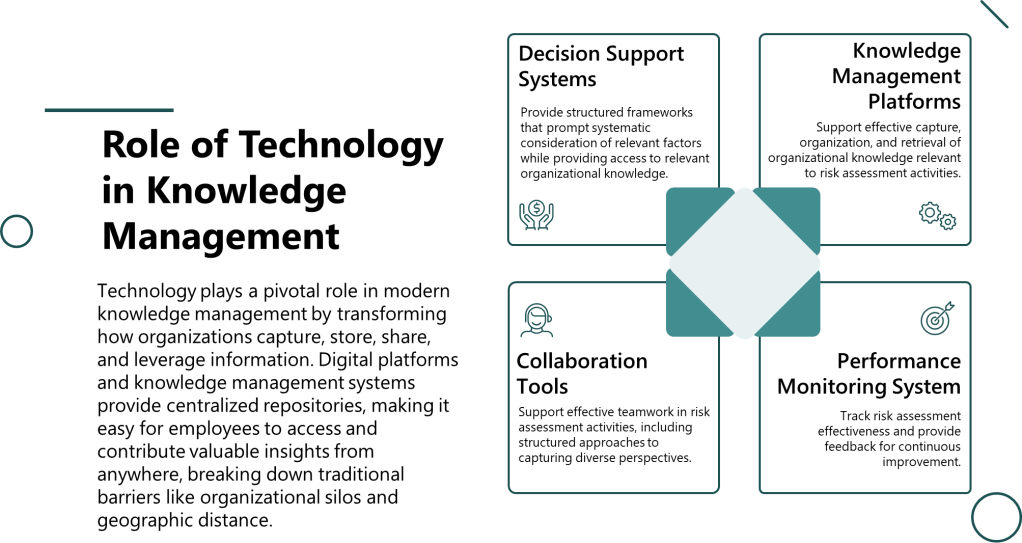

Technology and Tool Requirements for Effective Risk Management

Section 4’s emphasis on systematic, documented, and traceable risk management creates significant requirements for technology tools and platforms that can support sophisticated risk assessment and management processes. Organizations must invest in risk management systems that can capture, analyze, and track risks throughout complex system lifecycles while maintaining traceability to validation activities, change control processes, and operational decisions.

Risk assessment tools must support the multi-dimensional analysis required by Section 4, including product quality impacts, patient safety implications, and data integrity vulnerabilities. These tools must accommodate the dynamic nature of computerized system environments where risks evolve continuously due to technology changes, process modifications, and operational experience.

Integration with existing quality management systems, validation platforms, and operational monitoring tools becomes essential for maintaining consistency between risk assessments and other quality activities. Organizations must ensure that risk assessment results drive validation planning, change control decisions, and operational monitoring strategies while receiving feedback from these activities to update and improve risk assessments.

Documentation and traceability requirements create needs for sophisticated document management and workflow systems that can maintain relationships between risk assessments, system specifications, validation protocols, and operational procedures. Organizations must demonstrate clear traceability from risk identification through mitigation implementation and effectiveness verification.

Regulatory Expectations and Inspection Implications

Section 4’s comprehensive risk management requirements fundamentally change regulatory inspection dynamics by establishing risk assessment as the foundation for evaluating all computerized system compliance activities. Inspectors will expect to see documented, systematic, and scientifically defensible risk assessments that drive all system-related decisions from initial selection through ongoing operation.

The integration with ICH Q9(R1) provides inspectors with established criteria for evaluating risk management effectiveness including assessment methodology adequacy, stakeholder involvement appropriateness, and decision-making transparency. Organizations must demonstrate that their risk management processes meet ICH Q9(R1) standards while addressing the specific challenges of computerized system environments.

Risk-based validation approaches will receive increased scrutiny as inspectors evaluate whether validation scope and depth align appropriately with documented risk assessments. Organizations that cannot demonstrate clear traceability between risk assessments and validation activities will face significant compliance challenges regardless of validation execution quality.

The emphasis on system design and process modification as preferred risk mitigation strategies means that inspectors will evaluate whether organizations have adequately considered architectural and procedural alternatives to operational controls. Simply implementing extensive operational procedures to manage inherent system risks may no longer be considered adequate risk mitigation.

Ongoing risk management throughout the system lifecycle will become a key inspection focus as regulators evaluate whether organizations maintain current risk assessments and adjust control strategies based on operational experience, technology changes, and emerging threats. Static risk assessments that remain unchanged throughout system operation will be viewed as inadequate regardless of initial quality.

Strategic Implications for Pharmaceutical Operations

Section 4’s requirements represent a strategic inflection point for pharmaceutical organizations as they transition from compliance-driven computerized system approaches to risk-based digital strategies. Organizations that excel at implementing Section 4 requirements will gain competitive advantages through more effective system selection, optimized validation strategies, and superior operational risk management.

The emphasis on risk-driven system architecture creates opportunities for organizations to differentiate themselves through superior system design and integration strategies. Organizations that can demonstrate sophisticated risk assessment capabilities and implement appropriate system architectures will achieve better operational outcomes while reducing compliance costs and regulatory risks.

Risk-based validation approaches enabled by Section 4 provide opportunities for more efficient resource allocation and faster system implementation timelines. Organizations that invest in comprehensive risk assessment capabilities can focus validation efforts on areas of highest risk while reducing unnecessary validation activities for lower-risk system components and functions.

The integration with ICH Q9(R1) creates opportunities for pharmaceutical organizations to leverage their existing quality risk management capabilities for computerized system applications while enhancing overall organizational risk management maturity. Organizations can achieve synergies between product quality risk management and system risk management that improve both operational effectiveness and regulatory compliance.

Future Evolution and Continuous Improvement

Section 4’s lifecycle approach to risk management positions organizations for continuous improvement in risk assessment and mitigation capabilities as they gain operational experience and encounter new challenges. The requirement for ongoing risk evaluation creates feedback loops that enable organizations to refine their risk management approaches based on real-world performance and emerging best practices.

The dynamic nature of computerized system environments means that risk management capabilities must evolve continuously to address new technologies, changing threats, and evolving operational requirements. Organizations that establish robust risk management foundations under Section 4 will be better positioned to adapt to future regulatory changes and technology developments.

The integration with broader pharmaceutical quality systems creates opportunities for organizations to develop comprehensive risk management capabilities that span traditional manufacturing operations and modern digital infrastructure. This integration enables more sophisticated risk assessment and mitigation strategies that consider the full range of factors affecting product quality, patient safety, and data integrity.

Organizations that embrace Section 4’s requirements as strategic capabilities rather than compliance obligations will build sustainable competitive advantages through superior risk management that enables more effective system selection, optimized operational strategies, and enhanced regulatory relationships.

The Foundation for Digital Transformation

Section 4 ultimately serves as the scientific foundation for pharmaceutical digital transformation by providing the risk management framework necessary to evaluate, implement, and operate sophisticated computerized systems with appropriate confidence and control. The requirement for systematic, documented, and traceable risk assessment provides the methodology necessary to navigate the complex risk landscapes of modern pharmaceutical operations.

The emphasis on risk-driven system design creates the foundation for implementing advanced technologies including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automated process control with appropriate risk understanding and mitigation. Organizations that master Section 4’s requirements will be positioned to leverage these technologies effectively while maintaining regulatory compliance and operational control.

The lifecycle approach to risk management provides the framework necessary to manage the continuous evolution of computerized systems in dynamic business and regulatory environments. Organizations that implement Section 4 requirements effectively will build the capabilities necessary to adapt continuously to changing circumstances while maintaining consistent risk management standards.

Section 4 represents more than regulatory compliance—it establishes the scientific methodology that enables pharmaceutical organizations to harness the full potential of digital technologies while maintaining the rigorous risk management standards essential for protecting product quality, patient safety, and data integrity. Organizations that embrace this transformation will lead the industry’s evolution toward more sophisticated, efficient, and effective pharmaceutical operations.

| Requirement Area | Draft Annex 11 Section 4 (2025) | Current Annex 11 (2011) | ICH Q9(R1) 2023 | Implementation Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifecycle Application | QRM applied throughout entire lifecycle considering product quality, patient safety, data integrity | Risk management throughout lifecycle considering patient safety, data integrity, product quality | Quality risk management throughout product lifecycle | Requires continuous risk assessment processes rather than one-time validation activities |

| Risk Assessment Focus | Risks identified and analyzed per established procedure with ICH Q9(R1) methods | Risk assessment should consider patient safety, data integrity, product quality | Systematic risk identification, analysis, and evaluation | Mandates systematic procedures using proven methodologies rather than ad hoc approaches |

| Validation Strategy | Validation strategy and effort determined based on intended use and potential risks | Validation extent based on justified and documented risk assessment | Risk-based approach to validation and control strategies | Links validation scope directly to risk assessment outcomes, potentially reducing or increasing validation burden |

| Risk Mitigation | Risks mitigated to acceptable level through process/system design modifications | Risk mitigation not explicitly detailed | Risk control through reduction and acceptance strategies | Prioritizes system design changes over operational controls, potentially requiring architecture modifications |

| Data Integrity Risk | QRM principles assess data criticality, vulnerability, detection likelihood | Data integrity risk mentioned but not detailed | Data integrity risks as part of overall quality risk assessment | Requires sophisticated three-dimensional risk assessment for all data management activities |

| Documentation Requirements | Documented risk assessments required for all computerized systems | Risk assessment should be justified and documented | Documented, transparent, and reproducible risk management processes | Elevates documentation standards and requires traceability throughout system lifecycle |

| Integration with QRM | Fully integrated with ICH Q9(R1) quality risk management principles | General risk management principles | Core principle of pharmaceutical quality system | Creates mandatory alignment between system and product risk management activities |

| Ongoing Risk Review | Risk review required for changes and incidents throughout lifecycle | Risk review not explicitly required | Regular risk review based on new knowledge and experience | Establishes continuous risk monitoring as operational requirement rather than periodic activity |