In the Metrics Plan for Facility, Utility, System and Equipment that is being developed a focus is on effective commissioning, qualification, and validation processes.

To demonstrate the success of a CQV program we might brainstorm the following metrics.

Deviation and Non-Conformance Rates

- Track the number and severity of deviations related to commissioned, qualified and validated processes and FUSE elements.

- The effectiveness of CAPAs that involve CQV elements

Change Control Effectiveness

- Measure the number of successful changes implemented without issues

- Track the time taken to implement and qualify validate changes

Risk Reduction

- Quantify the reduction in high and medium risks identified during risk assessments as a result of CQV activities

- Monitor the effectiveness of risk mitigation strategies

Training and Competency

- Measure the percentage of personnel with up-to-date training on CQV procedures

- Track competency assessment scores for key validation personnel

Documentation Quality

- Measure the number of validation discrepancies found during reviews

- Track the time taken to approve validation documents

Supplier Performance

- Monitor supplier audit results related to validated systems or components

- Track supplier-related deviations or non-conformances

Regulatory Inspection Outcomes

- Track the number and severity of validation-related observations during inspections

- Measure the time taken to address and close out regulatory findings

Cost and Efficiency Metrics

- Measure the time and resources required to complete validation activities

- Track cost savings achieved through optimized CQV approaches

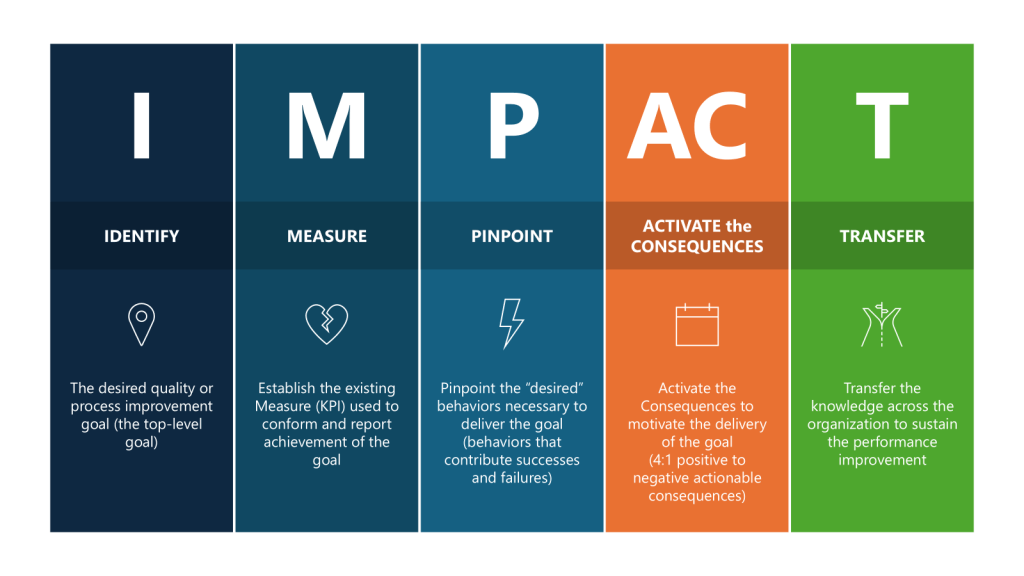

By tracking these metrics, we might be able to demonstrate a comprehensive and effective CQV program that aligns with regulatory expectations. Or we might just spend time measuring stuff that may not be tailored to our individual company’s processes, products, and risk profile. And quite frankly, will they influence the system the way we want? It’s time to pull out an IMPACT key behavior analysis to help us tailor a right-sized set of metrics.

The first thing to do is to go to first principles, to take a big step back and ask – what do I really want to improve?

The purpose of a CQV program is to provide documented evidence that facilities, systems, equipment and processes have been designed, installed and operate in accordance with predetermined specifications and quality attributes:

- To verify that critical aspects of a facility, utility system, equipment or process meet approved design specifications and quality attributes.

- To demonstrate that processes, equipment and systems are fit for their intended use and perform as expected to consistently produce a product meeting its quality attributes.

- To establish confidence that the manufacturing process is capable of consistently delivering quality product.

- To identify and understand sources of variability in the process to better control it.

- To detect potential problems early in development and prevent issues during routine production.

The ultimate measure of success is demonstrating and maintaining a validated state that ensures consistent production of safe and effective products meeting all quality requirements.

Focusing on the Impact is important. What are we truly concerned about for our CQV program. Based on that we come up with two main factors:

- The level of deviations that stem from root causes associated with our CQV program

- The readiness of FUSE elements for use (project adherence)

Reducing Deviations from CQV Activities

First, we gather data, what deviations are we looking for? These are the types of root causes that we will evaluate. Of course, your use of the 7Ms may vary, this list is to start conversation.

| Means | Automation or Interface Design Inadequate/Defective | Validated machine or computer system interface or automation failed to meet specification due to inadequate/defective design. |

| Means | Preventative Maintenance Inadequate | The preventive maintenance performed on the equipment was insufficient or not performed as required. |

| Means | Preventative Maintenance Not Defined | No preventive maintenance is defined for the equipment used. |

| Means | Equipment Defective/Damaged/Failure | The equipment used was defective or a specific component failed to operate as intended. |

| Means | Equipment Incorrect | Equipment required for the task was set up or used incorrectly or the wrong equipment was used for the task. |

| Means | Equipment Design Inadequate/Defective | The equipment was not designed or qualified to perform the task required or the equipment was defective, which prevented its normal operation. |

| Media | Facility Design | Improper or inadequate layout or construction of facility, area, or work station. |

| Methods | Calibration Frequency is Not Sufficient/Deficiency | Calibration interval is too long and/or calibration schedule is lacking. |

| Methods | Calibration/Validation Problem | An error occurred because of a data collection- related issue regarding calibration or validation. |

| Methods | System / Process Not Defined | The system/tool or the defined process to perform the task does not exist. |

Based on analysis of what is going on we can move into using a why-why technique to look at our layers.

| Why 1 | Why are deviations stemming from CQV events not at 0% Because unexpected issues or discrepancies arise after the commissioning, qualification, or validation processes Success factor needed for this step: Effectiveness of the CQV program Metric for this step: Adherence to CQV requirements |

| Why 2 (a) | Why are unexpected issues arising after CQV? Because of inadequate planning and resource constraints in the CQV process. Success Factor needed for this step: Appropriate project and resource planning Metric for this Step: Resource allocation |

| Why 3 (a) | Why are we not performing adequate resource planning? Because of the tight project timelines, and the involvement of multiple stakeholders with different areas of expertise Success Factor needed for this step: Cross-functional governance to implement risk methodologies to focus efforts on critical areas Metric for this Step: Risk Coverage Ratio measuring the percentage of identified critical risks that have been properly assessed and and mitigated through the cross-functional risk management process. This metric helps evaluate how effectively the governance structure is addressing the most important risks facing the organization. |

| Why 2 (b) | Why are unexpected issues arising after CQV? Because of poorly executed elements of the CQV process stemming from poorly written procedures and under-qualified staff. Success Factor needed for this step: Process Improvements and Training Qualification Metric for this Step: Performance to Maturity Plan |

There were somethings I definitely glossed over there, and forgive me for not providing numbers there, but I think you get the gist.

So now I’ve identified the I – How do we improve reliability of our CQV program, measured by reducing deviations. Let’s break out the rest.

| Parameters | Executed for CQV | |

| IDENTIFY | The desired quality or process improvement goal (the top-level goal) | Improve the effectiveness of the CQV program by taking actions to reduce deviations stemming from verification of FUSE and process. |

| MEASURE | Establish the existing Measure (KPI) used to conform and report achievement of the goal | Set a target reduction of deviations related to CQV activities. |

| Pinpoint | Pinpoint the “desired” behaviors necessary to deliver the goal (behaviors that contribute successes and failures) | Drive good project planning and project adherence. Promote and coach for enhanced attention to detail where “quality is everyone’s job.” Encourage a speak-up culture where concerns, issues or suggestions are shared in a timely manner in a neutral constructive forum. |

| ACTIVATE the CONSEQUENCES | Activate the Consequences to motivate the delivery of the goal (4:1 positive to negative actionable consequences) | Organize team briefings on consequences Review outcomes of project health Senior leadership celebrate/acknowledge Acknowledge and recognize improvements Motivate the team through team awards Measure success on individual deliverables through a Rubric |

| TRANSFER | Transfer the knowledge across the organization to sustain the performance improvement | Create learning teams Lessons learned are documented and shared Lunch-and-learn sessions Create improvement case studies |

From these two exercises I’ve now identified my lagging and leading indicators at the KPI and the KBI level.