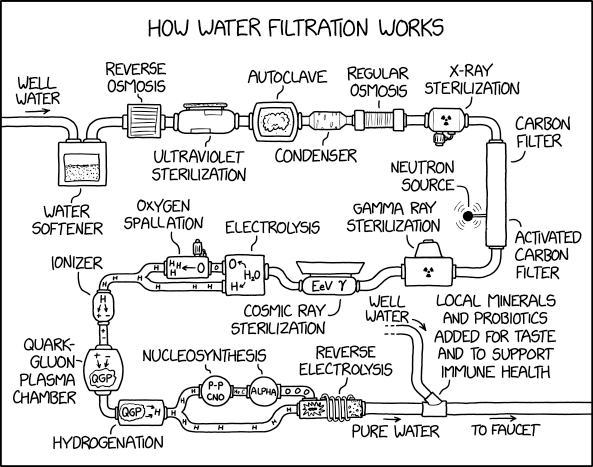

Everyone probably feels like the above illustration sooner or later about their water system.

The Critical Role of Water in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

In the pharmaceutical industry, we often joke that we’re primarily water companies that happen to make drugs on the side. This quip underscores a fundamental truth: water is a crucial component in drug manufacturing processes. Its purity and quality are paramount to ensuring the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products.

Why Water Quality Matters

Water is ubiquitous in pharmaceutical manufacturing, used in everything from cleaning equipment to serving as a key ingredient in many formulations. Given its importance, regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA have established stringent Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines for water systems in pharmaceutical facilities.

GMP Requirements for Water Systems

The GMPs mandate that water systems be meticulously designed, constructed, installed, commissioned, qualified, monitored, and maintained. The primary goal? Preventing microbiological contamination. This comprehensive approach encompasses several key areas:

- System Design: Water systems must be engineered to minimize the risk of contamination.

- Construction and Installation: Materials and methods used must meet high standards to ensure system integrity.

- Commissioning and Qualification: Rigorous testing is required to verify that the system performs as intended.

- Monitoring: Ongoing surveillance is necessary to detect any deviations from established parameters.

- Maintenance: Regular upkeep is crucial to maintain system performance and prevent degradation.

Key Regulatory Requirements

| Agency | Title | Year | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMA | Guideline on the quality of water for pharmaceutical use | 2020 | https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-quality-water-pharmaceutical-use_en.pdf |

| WHO | Good manufacturing practices: water for pharmaceutical use | 2012 | https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/medicines/norms-and-standards/guidelines/production/trs970-annex2-gmp-wate-pharmaceutical-use.pdf |

| US FDA | Guide to inspections of high purity water systems | 2016 | https://www.fda.gov/media/75927/download |

| PIC/S | Inspection of utilities | 2014 | https://picscheme.org/docview/1941 |

| US FDA | Water for pharmaceutical use | 2014 | https://www.fda.gov/media/88905/download |

| USP | <1231> Water for pharmaceutical purposes | 2020 | Not publicly available |

| USP | <543> Water Conductivity | 2020 | Not publicly available |

| USP | <85> Bacterial Endotoxins Test | 2020 | Not publicly available |

| USP | <643> Total Organic Carbon | 2020 | Not publicly available |

| Ph. Eur. | Monograph 0168 (Water for injections) | 2020 | Not publicly available |

| Ph. Eur. | Monograph 0008 (Purified water) | 2020 | Not publicly available |

Specific Measures for Contamination Prevention

To meet these GMP requirements, pharmaceutical manufacturers must implement several specific measures:

Minimizing Particulates

Particulate matter in water can compromise product quality and potentially harm patients. Filtration systems and regular cleaning protocols are essential to keep particulate levels in check.

Controlling Microbial Contamination

Microorganisms can proliferate rapidly in water systems if left unchecked. Strategies to prevent this include:

- Regular sanitization procedures

- Maintaining appropriate water temperatures

- Implementing effective water treatment technologies (e.g., UV light, ozonation)

Preventing Endotoxin Formation

Endotoxins, produced by certain bacteria, can be particularly problematic in pharmaceutical water systems. Measures to prevent endotoxin formation include:

- Minimizing areas where water can stagnate

- Ensuring complete drainage of pipes

- Regular system flushing

The Ongoing Challenge

Maintaining water quality in pharmaceutical manufacturing is not a one-time effort but an ongoing process. It requires constant vigilance, regular testing, and a commitment to continuous improvement. As regulations evolve and our understanding of potential contaminants grows, so too must our approaches to water system management.

Types of Water

These water types are defined and regulated by pharmacopeias such as the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.), and other regional standards. Pharmaceutical manufacturers must adhere to the specific requirements outlined in these references to ensure water quality and safety in drug production.

Potable Water

Potable water, also known as drinking water, may be used for some pharmaceuticals bt is more commonly used in cosmetics. It can also be used for cleanings walls and floors in non-asceptic areas.

Key points:

- Must comply with EPA standards or comparable regulations in the EU/Japan

- Can be used to manufacture drug substances (bulk drugs)

- Not suitable for preparing USP dosage forms or laboratory reagents

Purified Water (PW)

Purified water is widely used in pharmaceutical manufacturing for non-sterile preparations.

Specifications (USP <1231>):

- Conductivity: ≤1.3 μS/cm at 25°C

- Total organic carbon (TOC): ≤500 ppb

- Microbial limits: ≤100 CFU/mL

Applications:

- Non-parenteral preparations

- Cleaning equipment for non-parenteral products

- Preparation of some bulk chemicals

Water for Injection (WFI)

Water for Injection is used for parenteral drug products and has stricter quality standards.

Specifications (USP <1231>):

- Conductivity: ≤1.3 μS/cm at 25°C

- TOC: ≤500 ppb

- Bacterial endotoxins: <0.25 EU/mL

- Microbial limits: ≤10 CFU/100 mL

Production methods:

- Distillation

- Reverse osmosis (allowed by Ph. Eur. since 2017)

Sterile Water for Injection (SWFI)

SWFI is WFI that has been sterilized for direct administration.

Characteristics:

- Sterile

- Non-pyrogenic

- Packaged in single-dose containers

Highly Purified Water (HPW)

Previously included in the European Pharmacopoeia, but now discontinued.

| Type of Water | Description | USP Reference | EP Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potable Water | Meets drinking water standards, used for early stages of manufacturing | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Purified Water (PW) | Used for non-sterile preparations, cleaning equipment | USP <1231> | Ph. Eur. 0008 |

| Water for Injection (WFI) | Used for parenteral products, higher purity than PW | USP <1231> | Ph. Eur. 0169 |

| Sterile Water for Injection (SWFI) | WFI that has been sterilized for direct administration | USP <1231> | Ph. Eur. 0169 |

| Bacteriostatic Water for Injection | Contains bacteriostatic agents, for multiple-dose use | USP <1231> | Ph. Eur. 0169 |

| Sterile Water for Irrigation | Packaged in single-dose containers larger than 1L | USP <1231> | Ph. Eur. 1116 |

| Sterile Water for Inhalation | For use in inhalators, less stringent endotoxin levels | USP <1231> | Ph. Eur. 1116 |

| Water for Hemodialysis | Specially treated for use in hemodialysis, produced on-site | USP <1231> | Not specified |

Additional relevant USP chapters:

- USP <645>: Water for Pharmaceutical Purposes – Microbial Attributes

- USP <85>: Bacterial Endotoxins Test

Always refer to the most current versions of the pharmacopoeial monographs and regulatory guidelines for detailed information.

Good Water System Design

Hygienic and Sanitary Design

The cornerstone of any good water system is its hygienic and sanitary design. This principle encompasses several aspects:

- Smooth, cleanable surfaces: All surfaces in contact with water should be smooth, non-porous, and easily cleanable to prevent biofilm formation.

- Self-draining components: Pipes and tanks should be designed to drain completely, eliminating standing water that could harbor microorganisms.

- Accessibility: All parts of the system should be easily accessible for inspection, cleaning, and maintenance.

Material Selection

Choosing the right materials is crucial for maintaining water quality and system integrity:

- Corrosion resistance: Use materials that resist corrosion, such as stainless steel (316L grade for high-purity applications) or appropriate food-grade plastics.

- Smooth internal finish: Crevices are places where corrosion happens, electropolishing improves the resistance of stainless steel to corrosion.

- Leachate prevention: Select materials that do not leach harmful substances into the water, even under prolonged contact or elevated temperatures.

- Non-adsorptive surfaces: Avoid materials that may adsorb contaminants, which could later be released back into the water.

Microbial Control

Preventing microbial growth is essential for water system safety:

- Elimination of dead legs: Design piping to avoid areas where water can stagnate and microorganisms can proliferate.

- Temperature control: Maintain temperatures outside the optimal range for microbial growth (typically below 20°C or above 50°C).

- Regular sanitization: Incorporate features that allow for effective and frequent sanitization of the entire system.

System Integrity

Ensuring the system remains sealed and leak-free is critical:

- Proper sealing: Use appropriate gaskets and seals compatible with the system’s operating conditions.

- Pressure testing: Implement regular pressure tests to identify and address potential leaks promptly.

- Quality connections: Utilize sanitary fittings and connections designed for hygienic applications.

Cleaning and Sanitization Compatibility

The system must withstand regular cleaning and sanitization:

- Chemical resistance: Choose materials and components that can tolerate cleaning and sanitizing agents without degradation.

- Thermal stability: Ensure all parts can withstand thermal sanitization processes if applicable.

- CIP/SIP design: Incorporate Clean-in-Place (CIP) or Steam-in-Place (SIP) features for efficient and thorough cleaning.

Capacity and Performance

Meeting output requirements while maintaining quality is crucial:

- Proper sizing: Design the system to meet peak demand without compromising water quality or flow rates.

- Redundancy: Consider incorporating redundant components for critical parts to ensure continuous operation.

- Efficiency: Optimize the system layout to minimize pressure drops and energy consumption.

Monitoring and Control

Implement robust monitoring systems to ensure water quality:

- Sampling points: Strategically place sampling ports throughout the system for regular quality checks.

- Instrumentation: Install appropriate instruments to monitor critical parameters such as flow rate, pressure, temperature, and conductivity.

- Control systems: Implement automated control systems to maintain consistent water quality and system performance.

Regulatory Compliance

Ensure the system design meets all relevant regulatory requirements:

- Material compliance: Use only materials approved for contact with water in your specific application.

- Documentation: Maintain detailed documentation of system design, materials, and operating procedures.

- Validation: Conduct thorough system qualification to demonstrate consistent performance and quality.

By adhering to these principles, you can design a water system that not only meets your capacity requirements but also ensures the highest standards of safety and quality. Remember, good water system design is an ongoing process that requires regular review and updates to maintain its effectiveness over time.