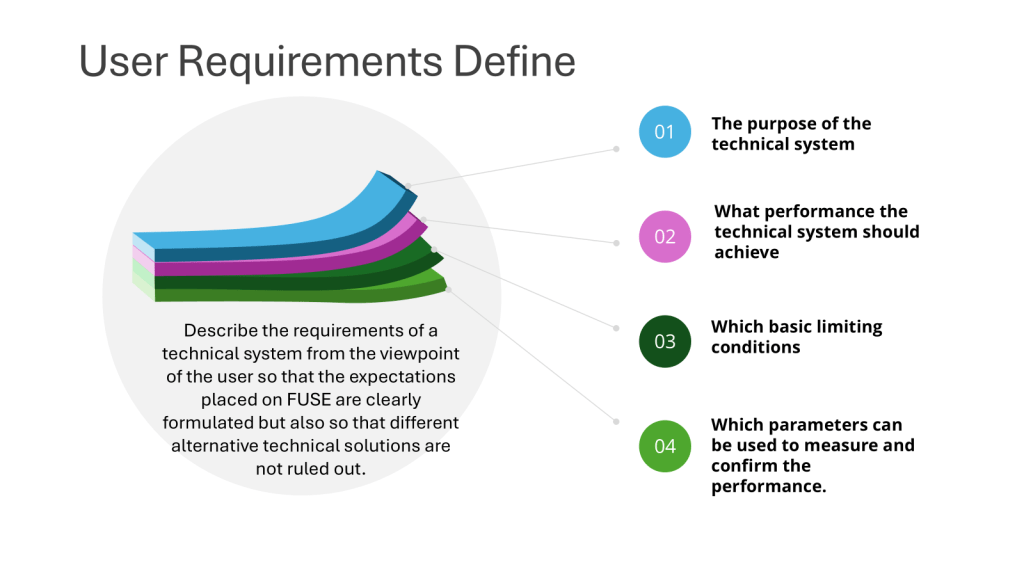

“The specification for equipment, facilities, utilities or systems should be defined in a URS and/or a functional specification. The essential elements of quality need to be built in at this stage and any GMP risks mitigated to an acceptable level. The URS should be a point of reference throughout the validation life cycle.” – Annex 15, Section 3.2, Eudralex Volume 4

User Requirement Specifications serve as a cornerstone of quality in pharmaceutical manufacturing. They are not merely bureaucratic documents but vital tools that ensure the safety, efficacy, and quality of pharmaceutical products.

Defining the Essentials

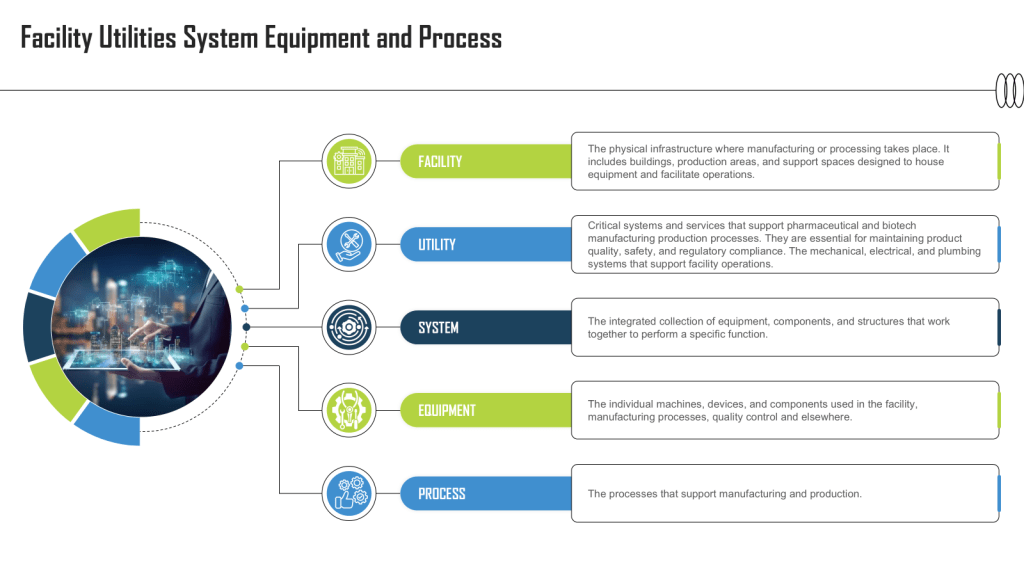

A well-crafted URS outlines the critical requirements for facilities, equipment, utilities, systems and processes in a regulated environment. It captures the fundamental aspects and scope of users’ needs, ensuring that all stakeholders have a clear understanding of what is expected from the final product or system.

Building Quality from the Ground Up

The phrase “essential elements of quality need to be built in at this stage” emphasizes the proactive approach to quality assurance. By incorporating quality considerations from the outset, manufacturers can:

- Minimize the risk of errors and defects

- Reduce the need for costly corrections later in the process

- Ensure compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards

Mitigating GMP Risks

Risk management is a crucial aspect of pharmaceutical manufacturing. The URS plays a vital role in identifying and addressing potential GMP risks early in the development process. By doing so, manufacturers can:

- Implement appropriate control measures

- Design systems with built-in safeguards

- Ensure that the final product meets regulatory requirements

The URS as a Living Document

One of the key points in the regulations is that the URS should be “a point of reference throughout the validation life cycle.” This underscores the dynamic nature of the URS and its ongoing importance.

Continuous Reference

Throughout the development, implementation, and operation of a system or equipment, the URS serves as:

- A benchmark for assessing progress

- A guide for making decisions

- A tool for resolving disputes or clarifying requirements

Adapting to Change

As projects evolve, the URS may need to be updated to reflect new insights, technological advancements, or changing regulatory requirements. This flexibility ensures that the final product remains aligned with user needs and regulatory expectations.

Practical Implications

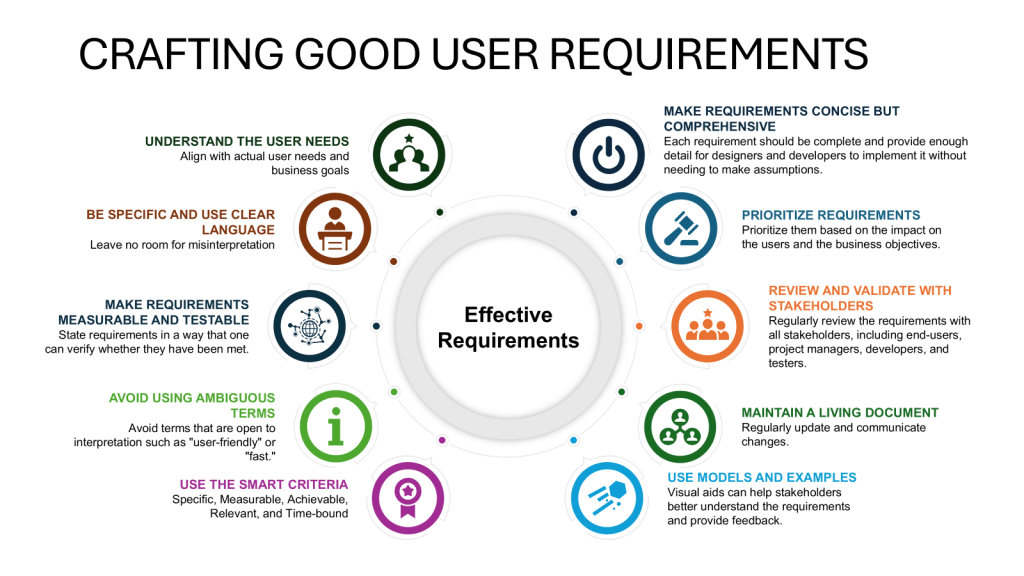

- Involve multidisciplinary teams in creating the URS, including representatives from quality assurance, engineering, production, and regulatory affairs.

- Conduct thorough risk assessments to identify potential GMP risks and incorporate mitigation strategies into the URS.

- Ensure clear, objectively stated requirements that are verifiable during testing and commissioning.

- Align the URS with company objectives and strategies to ensure long-term relevance and support.

- Implement robust version control and change management processes for the URS throughout the validation lifecycle.

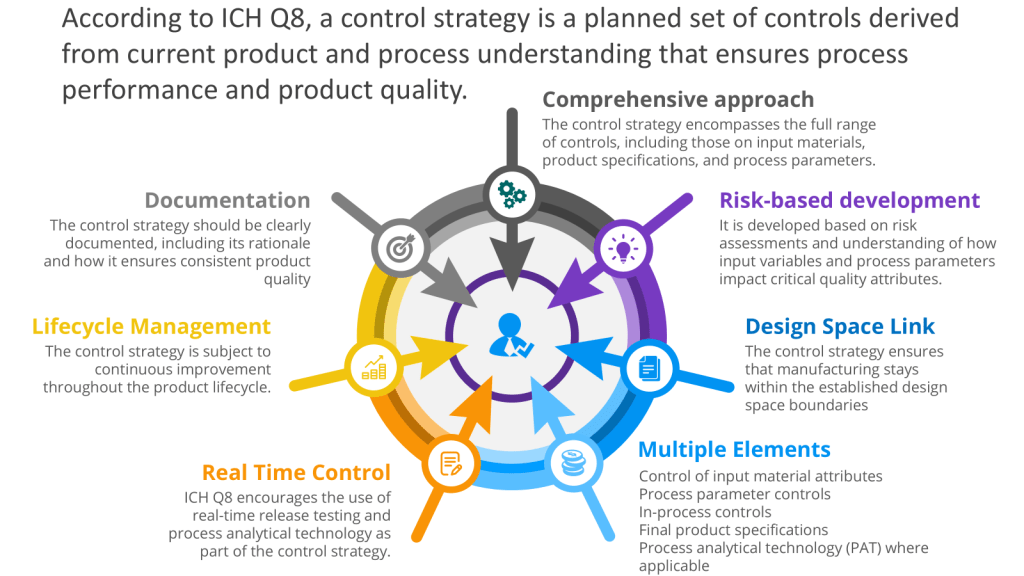

Executing the Control Space from the Design Space

The User Requirements Specification (URS) is a mechanism for executing the control space, from the design space as outlined in ICH Q8. To understand that, let’s discuss the path from a Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) to Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) to Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) with Proven Acceptable Ranges (PARs), which is a crucial journey in pharmaceutical development using Quality by Design (QbD) principles. This systematic approach ensures that the final product meets the desired quality standards and user needs.

It is important to remember that this is usually a set of user requirements specifications, respecting the system boundaries.

From QTPP to CQAs

The journey begins with defining the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP). The QTPP is a comprehensive summary of the quality characteristics that a drug product should possess to ensure its safety, efficacy, and overall quality. It serves as the foundation for product development and includes considerations such as:

- Dosage strength

- Delivery system

- Dosage form

- Container system

- Purity

- Stability

- Sterility

Once the QTPP is established, the next step is to identify the Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs). CQAs are physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that should be within appropriate limits to ensure the desired product quality. These attributes are derived from the QTPP and are critical to the safety and efficacy of the product.

From CQAs to CPPs

With the CQAs identified, the focus shifts to determining the Critical Process Parameters (CPPs). CPPs are process variables that have a direct impact on the CQAs. These parameters must be monitored and controlled to ensure that the product consistently meets the desired quality standards. Examples of CPPs include:

- Temperature

- pH

- Cooling rate

- Rotation speed

The relationship between CQAs and CPPs is established through risk assessment, experimentation, and data analysis. This step often involves Design of Experiments (DoE) to understand how changes in CPPs affect the CQAs. This is Process Characterization.

Establishing PARs

For each CPP, a Proven Acceptable Range (PAR) is determined. The PAR represents the operating range within which the CPP can vary while still ensuring that the CQAs meet the required specifications. PARs are established through rigorous testing and validation processes, often utilizing statistical tools and models.

Build the Requirements for the CPPs

The CPPs with PARs are process parameters that can affect critical quality attributes of the product and must be controlled within predetermined ranges. These are translated into user requirements. Many will specifically label these as Product User Requirements (PUR) to denote they are linked to the overall product capability. This helps to guide risk assessments and develop an overall verification approach.

Most of Us End Up on the Less than Happy Path

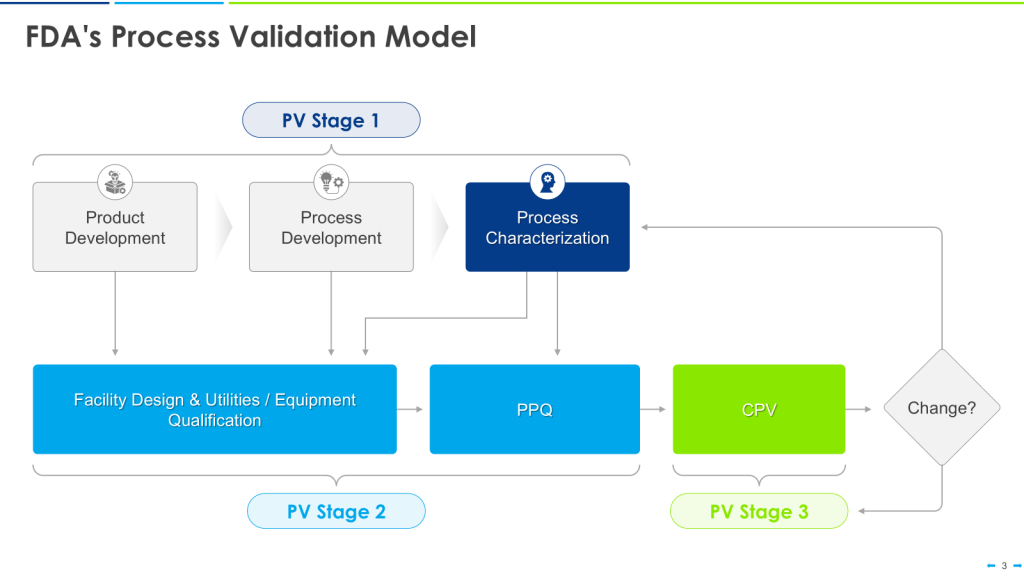

This approach is the happy path that aligns nicely with the FDA’s Process Validation Model.

This can quickly break down in the real world. Most of us go into CDMOs with already qualified equipment. We have platforms on which we’ve qualified our equipment, too. We don’t know the CPPs until just before PPQ.

This makes the user requirements even more important as living documents. Yes, we’ve qualified our equipment for these large ranges. Now that we have the CPPs, we update the user requirements for the Product User Requirements, perform an overall assessment of the gaps, and, with a risk-based approach, do additional verification activations either before or as part of Process Performance Qualification (PPQ).