Maintaining process closure is crucial for ensuring product quality and safety in biotechnology manufacturing, especially when using single-use systems (SUS). This approach is an integral part of the contamination control strategy (CCS). To validate process closure in SUS-based biotech manufacturing, a comprehensive method is necessary, incorporating:

- Risk assessment

- Thorough testing

- Ongoing monitoring

By employing risk analysis tools such as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), manufacturers can identify potential weaknesses in their processes. Additionally, addressing all four layers of protection helps ensure process integrity and product safety. This risk-based approach to process closure validation is essential for maintaining the high standards required in biotechnology manufacturing, including meeting Annex 1.

Understanding Process Closure

Process closure refers to the isolation of the manufacturing process from the external environment to prevent contamination. In biotech, this is particularly crucial due to the sensitivity of biological products and the potential for microbial contamination.

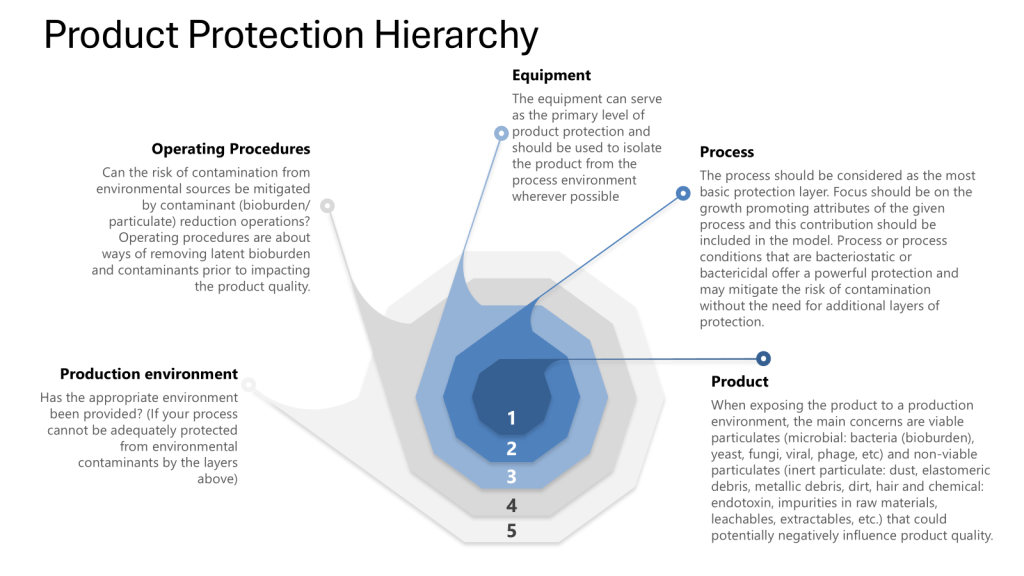

The Four Layers of Protection

Throughout this process it is important to apply the four layers of protection that form the foundation of a robust contamination control strategy:

- Process: The inherent ability of the process to prevent or control contamination

- Equipment: The design and functionality of equipment to maintain closure

- Operating Procedures: The practices and protocols followed by personnel

- Production Environment: The controlled environment surrounding the process

I was discussing this with some colleagues this week (preparing for some risk assessments) and I was reminded that we really should put the Patient in at the center, the zero. Truer words have never been spoken as the patient truly is our zeroth law, the fundamental principle of the GxPs.

Key Steps for Validating Process Closure

Risk Assessment

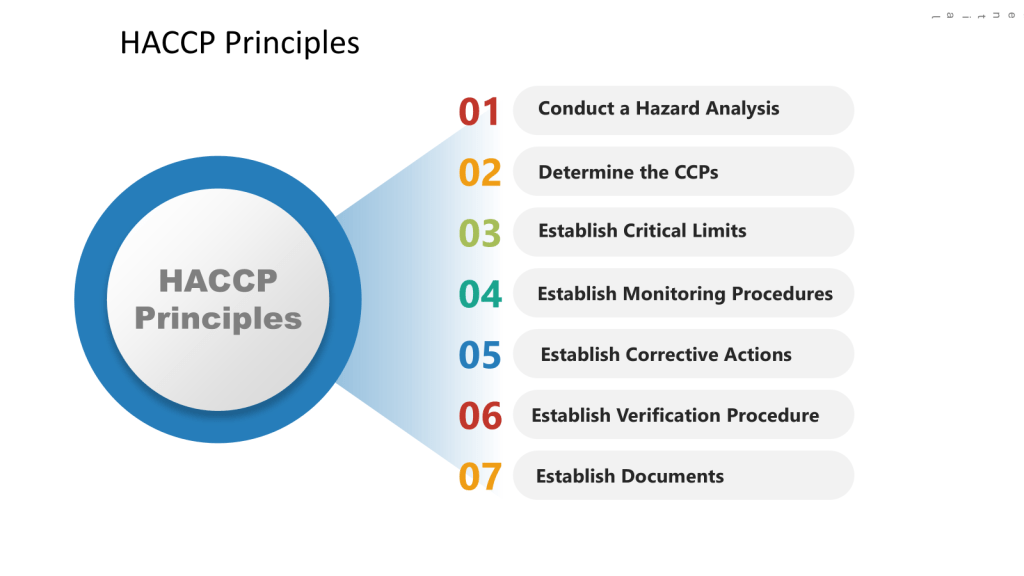

Start with a comprehensive risk assessment using tools such as HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) and FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis). It is important to remember this is not a one or another, but a multi-tiered approach where you first determine the hazards through the HACCP and then drill down into failures through an FMEA.

HACCP Approach

In the HACCP we will apply a systematic, preventative approach to identify hazards in the process with the aim to produce a documented plan to control these scenarios.

a) Conduct a hazard analysis

b) Identify Critical Control Points (CCPs)

c) Establish critical limits

d) Implement monitoring procedures

e) Define corrective actions

f) Establish verification procedures

g) Maintain documentation and records

FMEA Considerations

In the FMEA we will look for ways the process fails, focusing on the SUS components. We will evaluate failures at each level of control (process, equipment, operating procedure and environment).

- Identify potential failure modes in the SUS components

- Assess the severity, occurrence, and detectability of each failure mode

- Calculate Risk Priority Numbers (RPN) to prioritize risks

Verification

Utilizing these risk assessments, define the user requirements specification (URS) for the SUS, focusing on critical aspects that could impact product quality and patient safety. This should include:

- Process requirements (e.g. working volumes, flow rates, pressure ranges)

- Material compatibility requirements

- Sterility/bioburden control requirements

- Leachables/extractables requirements

- Integrity testing requirements

- Connectivity and interface requirements

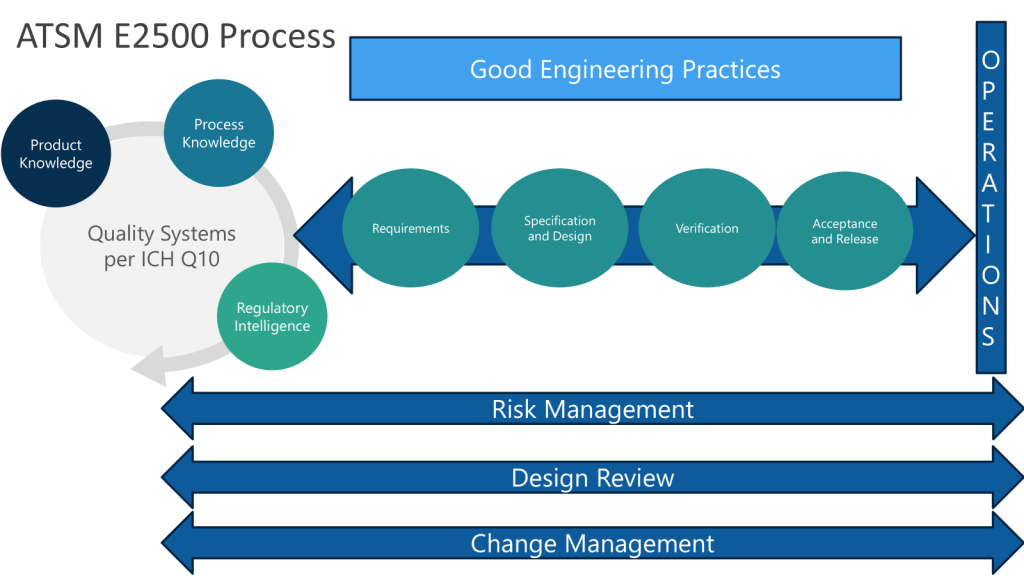

Following the ASTM E2500 approach, when we conduct the design review of the proposed SUS configuration, to evaluate how well it meets the URS, we want to ensure we cover:

- Overall system design and component selection

- Materials of construction

- Sterilization/sanitization approach

- Integrity assurance measures

- Sampling and monitoring capabilities

- Automation and control strategy

Circle back to the HACCP and FMEA to ensure they appropriately cover critical aspects like:

- Loss of sterility/integrity

- Leachables/extractables introduction

- Bioburden control failures

- Cross-contamination risks

- Process parameter deviations

These risk assessments will define critical control parameters and acceptance criteria based on the risk assessment. These will form the basis for verification testing. We will through our verification plan have an appropriate approach to:

- Verify proper installation of SUS components

- Check integrity of connections and seals

- Confirm correct placement of sensors and monitoring devices

- Document as-built system configuration

- Test system integrity under various operating conditions

- Perform leak tests on connections and seals

- Validate sterilization processes for SUS components

- Verify functionality of critical sensors and control

- Run simulated production cycles

- Monitor for contamination using sensitive detection methods

- Verify maintenance of sterility throughout the process

- Assess product quality attributes

The verification strategy will leverage a variety of supplier documentation and internal testing.

Closure Analysis Risk Assessment (CLARA)

Acceptance and release will be to perform a detailed CLARA to:

- Identify all potential points of contamination ingress

- Assess the effectiveness of closure mechanisms

- Evaluate the robustness of aseptic connections

- Determine the impact of manual interventions on system closure

On Going Use

Coming out of our HACCP we will have a monitoring and verification plan, this will include some important aspects based on our CCPs.

- Integrity Testing

- Implement routine integrity testing protocols for SUS components

- Utilize methods such as pressure decay tests or helium leak detection

- Establish acceptance criteria for integrity tests

- Environmental Monitoring

- Develop a comprehensive environmental monitoring program

- Include viable and non-viable particle monitoring

- Establish alert and action limits for environmental contaminants

- Operator Training and Qualification

- Develop detailed SOPs for SUS handling and assembly

- Implement a rigorous training program for operators

- Qualify operators through practical assessments

- Change Control and Continuous Improvement

- Establish a robust change control process for any modifications to the SUS or process

- Regularly review and update risk assessments based on new data or changes

- Implement a continuous improvement program to enhance process closure

Leveraging the Four Layers of Protection

Throughout the validation process, ensure that each layer of protection is addressed:

- Process:

- Optimize process parameters to minimize contamination risks

- Implement in-process controls to detect deviations

- Equipment:

- Validate the design and functionality of SUS components

- Ensure proper integration of SUS with existing equipment

- Operating Procedures:

- Develop and validate aseptic techniques for SUS handling

- Implement procedures for system assembly and disassembly

- Production Environment:

- Qualify the cleanroom environment

- Validate HVAC systems and air filtration

Remember that validation is an ongoing process. Regular reviews, updates to risk assessments, and incorporation of new technologies and best practices are essential for maintaining a state of control in biotech manufacturing using single-use systems.

Connected to the Contamination Control Strategy

Closed systems are a key element of the overall contamination control strategy with closed processing and closed systems now accepted as the most effective contamination control risk mitigation strategy. I might not be able to manufacture in the woods yet, but darn if I won’t keep trying.

They serve as a primary barrier to prevent contamination from the manufacturing environment by helping to mitigate the risk of contamination by isolating the product from the surrounding environment. Closed systems are the key protective measure to prevent contamination from the manufacturing environment and cross-contamination from neighboring operations.

The risk assessments leveraged during the implementation of closed systems are a crucial part of developing an effective CCS and will communicate the (ideally) robust methods used to protect products from environmental contamination and cross-contamination. This is tied into the facility design, environmental controls, risk assessments, and overall manufacturing strategies, which are the key components of a comprehensive CCS.