Risk assessments, problem solving and making good decisions need teams, but any team has challenges in group think it must overcome. Ensuring your facilitators, team leaders and sponsors are aware and trained on these biases will help lead to deal with subjectivity, understand uncertainty and drive to better outcomes. But no matter how much work you do there, it won’t make enough of a difference until you’ve built a culture of quality and excellence.

The mindsets we are trying to build into our culture will strive to overcome a few biases in our teams that lead to subjectivity.

Bias Toward Fitting In

We have a natural desire to want to fit in. This tendency leads to two challenges:

Challenge #1: Believing we need to conform. Early in life, we realize that there are tangible benefits to be gained from following social and organizational norms and rules. As a result, we make a significant effort to learn and adhere to written and unwritten codes of behavior at work. But here’s the catch: Doing so limits what we bring to the organization.

Challenge #2: Failure to use one’s strengths. When employees conform to what they think the organization wants, they are less likely to be themselves and to draw on their strengths. When people feel free to stand apart from the crowd, they can exercise their signature strengths (such as curiosity, love for learning, and perseverance), identify opportunities for improvement, and suggest ways to exploit them. But all too often, individuals are afraid of rocking the boat.

We need to use several methods to combat the bias toward fitting in. These need to start at the cultural level. Risk management, problem solving and decision making only overcome biases when embedded in a wider, effective culture.

Encourage people to cultivate their strengths. To motivate and support employees, some companies allow them to spend a certain portion of their time doing work of their own choosing. Although this is a great idea, we need to build our organization to help individuals apply their strengths every day as a normal part of their jobs.

Managers need to help individuals identify and develop their fortes—and not just by discussing them in annual performance reviews. Annual performance reviews are horribly ineffective. Just by using “appreciation jolt”, positive feedback., can start to improve the culture. It’s particularly potent when friends, family, mentors, and coworkers share stories about how the person excels. These stories trigger positive emotions, cause us to realize the impact that we have on others, and make us more likely to continue capitalizing on our signature strengths rather than just trying to fit in.

Managers should ask themselves the following questions: Do I know what my employees’ talents and passions are? Am I talking to them about what they do well and where they can improve? Do our goals and objectives include making maximum use of employees’ strengths?

Increase awareness and engage workers. If people don’t see an issue, you can’t expect them to speak up about it.

Model good behavior. Employees take their cues from the managers who lead them.

Bias Toward Experts

This is going to sound counter-intuitive, especially since expertise is so critical. Yet our biases about experts can cause a few challenges.

Challenge #1: An overly narrow view of expertise. Organizations tend to define “expert” too narrowly, relying on indicators such as titles, degrees, and years of experience. However, experience is a multidimensional construct. Different types of experience—including time spent on the front line, with a customer or working with particular people—contribute to understanding a problem in detail and creating a solution.

A bias toward experts can also lead people to misunderstand the potential drawbacks that come with increased time and practice in the job. Though experience improves efficiency and effectiveness, it can also make people more resistant to change and more likely to dismiss information that conflicts with their views.

Challenge #2: Inadequate frontline involvement. Frontline employees—the people directly involved in creating, selling, delivering, and servicing offerings and interacting with customers—are frequently in the best position to spot and solve problems. Too often, though, they aren’t empowered to do so.

The following tactics can help organizations overcome weaknesses of the expert bias.

Encourage workers to own problems that affect them. Make sure that your organization is adhering to the principle that the person who experiences a problem should fix it when and where it occurs. This prevents workers from relying too heavily on experts and helps them avoid making the same mistakes again. Tackling the problem immediately, when the relevant information is still fresh, increases the chances that it will be successfully resolved. Build a culture rich with problem-solving and risk management skills and behaviors.

Give workers different kinds of experience. Recognize that both doing the same task repeatedly (“specialized experience”) and switching between different tasks (“varied experience”) have benefits. Yes, Over the course of a single day, a specialized approach is usually fastest. But over time, switching activities across days promotes learning and kept workers more engaged. Both specialization and variety are important to continuous learning.

Empower employees to use their experience. Organizations should aggressively seek to identify and remove barriers that prevent individuals from using their expertise. Solving the customer’s problems in innovative, value-creating ways—not navigating organizational impediments— should be the challenging part of one’s job.

In short we need to build the capability to leverage all level of experts, and not just a few in their ivory tower.

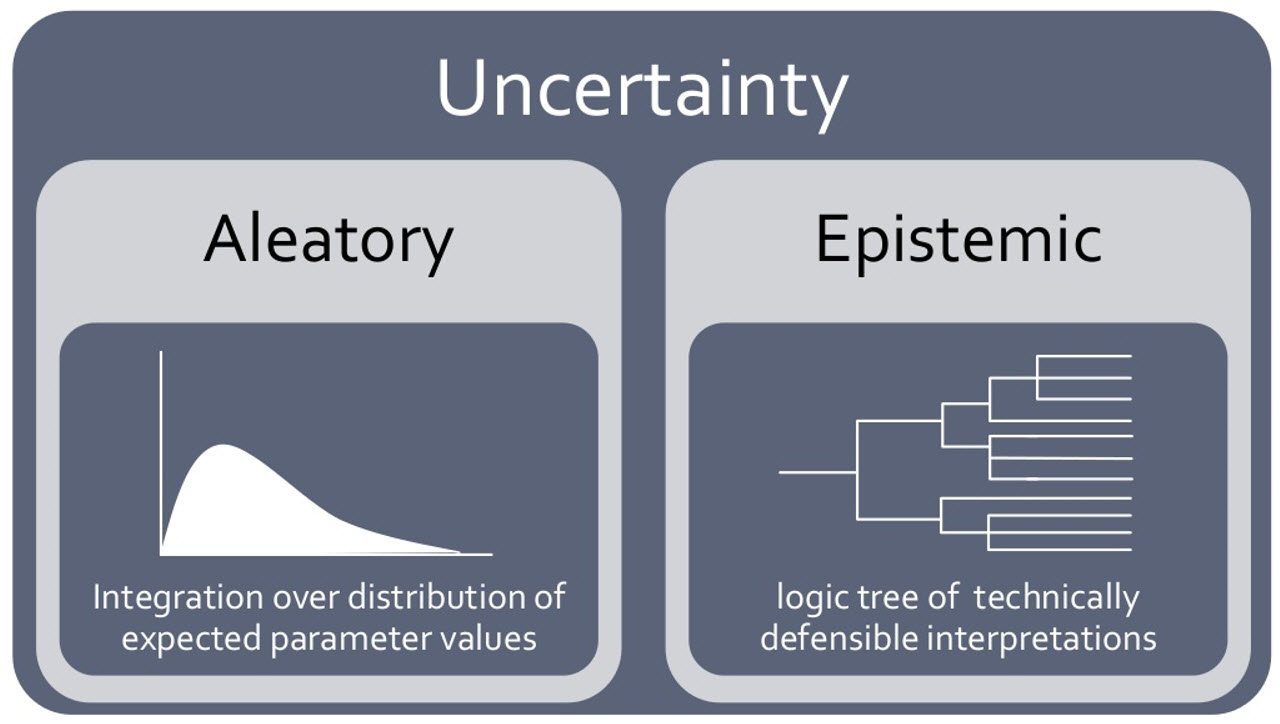

These two biases can be overcome and through that we can start building the mindsets to deal effectively with subjectivity and uncertainty. Going further, build the following as part of our team activities as sort of a quality control checklist:

- Check for self-interest bias

- Check for the affect heuristic. Has the team fallen in love with its own output?

- Check for group think. Were dissenting views explored adequately?

- Check for saliency bias. Is this routed in past successes?

- Check for confirmation bias.

- Check for availability bias

- Check for anchoring bias

- Check for halo effect

- Check for sunk cost fallacy and endowment effect

- Check for overconfidence, planning fallacy, optimistic biases, competitor neglect

- Check for disaster neglect. Have the team conduct a post-mortem: Imagine that the worst has happened and develop a story about its causes.

- Check for loss aversion