Energy Safety Canada recently published a white paper on causal reasoning that offers valuable insights for quality professionals across industries. As someone who has spent decades examining how we investigate deviations and perform root cause analysis, I found their framework refreshing and remarkably aligned with the challenges we face in pharmaceutical quality. The paper proposes a fundamental shift in how we approach investigations, moving from what they call “negative reasoning” to “causal reasoning” that could significantly improve our ability to prevent recurring issues and drive meaningful improvement.

The Problem with Traditional Root Cause Analysis

Many of us in quality have experienced the frustration of seeing the same types of deviations recur despite thorough investigations and seemingly robust CAPAs. The Energy Safety Canada white paper offers a compelling explanation for this phenomenon: our investigations often focus on what did not happen rather than what actually occurred.

This approach, which the authors term “negative reasoning,” leads investigators to identify counterfactuals-things that did not occur, such as “operators not following procedures” or “personnel not stopping work when they should have”. The problem is fundamental: what was not happening cannot create the outcomes we experienced. As the authors aptly state, these counterfactuals “exist only in retrospection and never actually influenced events,” yet they dominate many of our investigation conclusions.

This insight resonates strongly with what I’ve observed in pharmaceutical quality. Six years ago the MHRA’s 2019 citation of 210 companies for inadequate root cause analysis and CAPA development – including 6 critical findings – takes on renewed significance in light of Sanofi’s 2025 FDA warning letter. While most cited organizations likely believed their investigation processes were robust (as Sanofi presumably did before their contamination failures surfaced), these parallel cases across regulatory bodies and years expose a persistent industry-wide disconnect between perceived and actual investigation effectiveness. These continued failures exemplify how superficial root cause analysis creates dangerous illusions of control – precisely the systemic flaw the MHRA data highlighted six years prior.

Negative Reasoning vs. Causal Reasoning: A Critical Distinction

The white paper makes a distinction that I find particularly valuable: negative reasoning seeks to explain outcomes based on what was missing from the system, while causal reasoning looks for what was actually present or what happened. This difference may seem subtle, but it fundamentally changes the nature and outcomes of our investigations.

When we use negative reasoning, we create what the white paper calls “an illusion of cause without being causal”. We identify things like “failure to follow procedures” or “inadequate risk assessment,” which may feel satisfying but don’t explain why those conditions existed in the first place. These conclusions often lead to generic corrective actions that fail to address underlying issues.

In contrast, causal reasoning requires statements that have time, place, and magnitude. It focuses on what was necessary and sufficient to create the effect, building a logically tight cause-and-effect diagram. This approach helps reveal how work is actually done rather than comparing reality to an imagined ideal.

This distinction parallels the gap between “work-as-imagined” (the black line) and “work-as-done” (the blue line). Too often, our investigations focus only on deviations from work-as-imagined without trying to understand why work-as-done developed differently.

A Tale of Two Analyses: The Power of Causal Reasoning

The white paper presents a compelling case study involving a propane release and operator injury that illustrates the difference between these two approaches. When initially analyzed through negative reasoning, investigators concluded the operator:

- Used an improper tool

- Deviated from good practice

- Failed to recognize hazards

- Failed to learn from past experiences

These conclusions placed blame squarely on the individual and led leadership to consider terminating the operator.

However, when the same incident was examined through causal reasoning, a different picture emerged:

- The operator used the pipe wrench because it was available at the pump specifically for this purpose

- The pipe wrench had been deliberately left at that location because operators knew the valve was hard to close

- The operator acted quickly because he perceived a risk to the plant and colleagues

- Leadership had actually endorsed this workaround four years earlier during a turnaround

This causally reasoned analysis revealed that what appeared to be an individual failure was actually a system-level issue that had been normalized over time. Rather than punishing the operator, leadership recognized their own role in creating the conditions for the incident and implemented systemic improvements.

This example reminded me of our discussions on barrier analysis, where we examine barriers that failed, weren’t used, or didn’t exist. But causal reasoning takes this further by exploring why those conditions existed in the first place, creating a much richer understanding of how work actually happens.

First 24 Hours: Where Causal Reasoning Meets The Golden Day

In my recent post on “The Golden Start to a Deviation Investigation,” I emphasized how critical the first 24 hours are after discovering a deviation. This initial window represents our best opportunity to capture accurate information and set the stage for a successful investigation. The Energy Safety Canada white paper complements this concept perfectly by providing guidance on how to use those critical hours effectively.

When we apply causal reasoning during these early stages, we focus on collecting specific, factual information about what actually occurred rather than immediately jumping to what should have happened. This means documenting events with specificity (time, place, magnitude) and avoiding premature judgments about deviations from procedures or expectations.

As I’ve previously noted, clear and precise problem definition forms the foundation of any effective investigation. Causal reasoning enhances this process by ensuring we document using specific, factual language that describes what occurred rather than what didn’t happen. This creates a much stronger foundation for the entire investigation.

Beyond Human Error: System Thinking and Leadership’s Role

One of the most persistent challenges in our field is the tendency to attribute events to “human error.” As I’ve discussed before, when human error is suspected or identified as the cause, this should be justified only after ensuring that process, procedural, or system-based errors have not been overlooked. The white paper reinforces this point, noting that human actions and decisions are influenced by the system in which people work.

In fact, the paper presents a hierarchy of causes that resonates strongly with systems thinking principles I’ve advocated for previously. Outcomes arise from physical mechanisms influenced by human actions and decisions, which are in turn governed by systemic factors. If we only address physical mechanisms or human behaviors without changing the system, performance will eventually migrate back to where it has always been.

This connects directly to what I’ve written about quality culture being fundamental to providing quality. The white paper emphasizes that leadership involvement is directly correlated with performance improvement. When leaders engage to set conditions and provide resources, they create an environment where investigations can reveal systemic issues rather than just identify procedural deviations or human errors.

Implementing Causal Reasoning in Pharmaceutical Quality

For pharmaceutical quality professionals looking to implement causal reasoning in their investigation processes, I recommend starting with these practical steps:

1. Develop Investigator Competencies

As I’ve discussed in my analysis of Sanofi’s FDA warning letter, having competent investigators is crucial. Organizations should:

- Define required competencies for investigators

- Provide comprehensive training on causal reasoning techniques

- Implement mentoring programs for new investigators

- Regularly assess and refresh investigator skills

2. Shift from Counterfactuals to Causal Statements

Review your recent investigations and look for counterfactual statements like “operators did not follow the procedure.” Replace these with causal statements that describe what actually happened and why it made sense to the people involved at the time.

3. Implement a Sponsor-Driven Approach

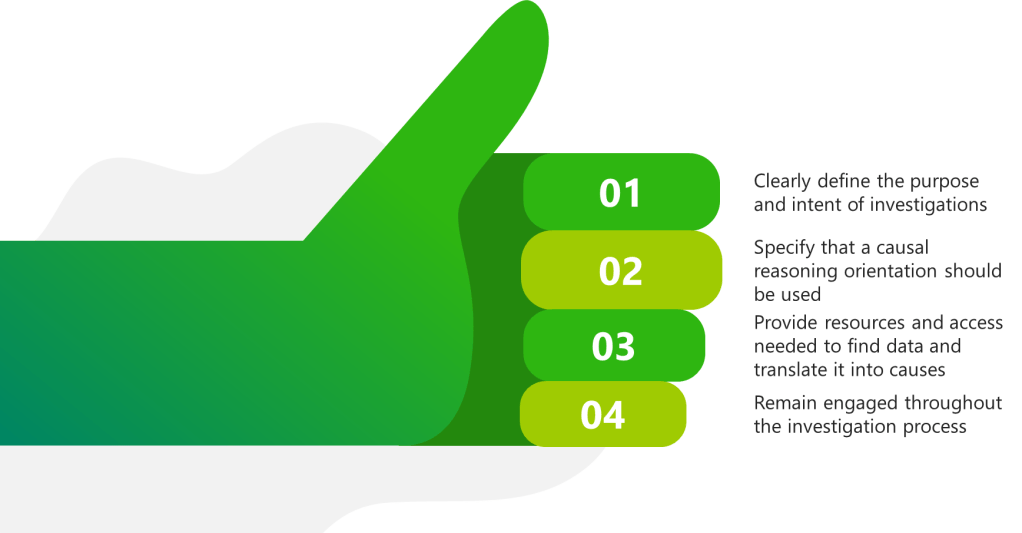

The white paper emphasizes the importance of investigation sponsors (otherwise known as Area Managers) who set clear conditions and expectations. This aligns perfectly with my belief that quality culture requires alignment between top management behavior and quality system philosophy. Sponsors should:

- Clearly define the purpose and intent of investigations

- Specify that a causal reasoning orientation should be used

- Provide resources and access needed to find data and translate it into causes

- Remain engaged throughout the investigation process

4. Use Structured Causal Analysis Tools

While the M-based frameworks I’ve discussed previously (4M, 5M, 6M) remain valuable for organizing contributing factors, they should be complemented with tools that support causal reasoning. The Cause-Consequence Analysis (CCA) I described in a recent post offers one such approach, combining elements of fault tree analysis and event tree analysis to provide a holistic view of risk scenarios.

From Understanding to Improvement

The Energy Safety Canada white paper’s emphasis on causal reasoning represents a valuable contribution to how we think about investigations across industries. For pharmaceutical quality professionals, this approach offers a way to move beyond compliance-focused investigations to truly understand how our systems operate and how to improve them.

As the authors note, “The capacity for an investigation to improve performance is dependent on the type of reasoning used by investigators”. By adopting causal reasoning, we can build investigations that reveal how work actually happens rather than simply identifying deviations from how we imagine it should happen.

This approach aligns perfectly with my long-standing belief that without a strong quality culture, people will not be ready to commit and involve themselves fully in building and supporting a robust quality management system. Causal reasoning creates the transparency and learning that form the foundation of such a culture.

I encourage quality professionals to download and read the full white paper, reflect on their current investigation practices, and consider how causal reasoning might enhance their approach to understanding and preventing deviations. The most important questions to consider are:

- Do your investigation conclusions focus on what didn’t happen rather than what did?

- How often do you identify “human error” without exploring the system conditions that made that error likely?

- Are your leaders engaged as sponsors who set conditions for successful investigations?

- What barriers exist in your organization that prevent learning from events?

As we continue to evolve our understanding of quality and safety, approaches like causal reasoning offer valuable tools for creating the transparency needed to navigate complexity and drive meaningful improvement.