Continuous Process Verification (CPV) represents the final and most dynamic stage of the FDA’s process validation lifecycle, designed to ensure manufacturing processes remain validated during routine production. The methodology for CPV and the selection of appropriate tools are deeply rooted in the FDA’s 2011 guidance, Process Validation: General Principles and Practices, which emphasizes a science- and risk-based approach to quality assurance. This blog post examines how CPV methodologies align with regulatory frameworks and how tools are selected to meet compliance and operational objectives.

CPV Methodology: Anchored in the FDA’s Lifecycle Approach

The FDA’s process validation framework divides activities into three stages: Process Design (Stage 1), Process Qualification (Stage 2), and Continued Process Verification (Stage 3). CPV, as Stage 3, is not an isolated activity but a continuation of the knowledge gained in earlier stages. This lifecycle approach is our framework.

Stage 1: Process Design

During Stage 1, manufacturers define Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) through risk assessments and experimental design. This phase establishes the scientific basis for monitoring and control strategies. For example, if a parameter’s variability is inherently low (e.g., clustering near the Limit of Quantification, or LOQ), this knowledge informs later decisions about CPV tools.

Stage 2: Process Qualification

Stage 2 confirms that the process, when operated within established parameters, consistently produces quality products. Data from this stage—such as process capability indices (Cpk/Ppk)—provide baseline metrics for CPV. For instance, a high Cpk (>2) for a parameter near LOQ signals that traditional control charts may be inappropriate due to limited variability.

Stage 3: Continued Process Verification

CPV methodology is defined by two pillars:

- Ongoing Monitoring: Continuous collection and analysis of CPP/CQA data.

- Adaptive Control: Adjustments to maintain process control, informed by statistical and risk-based insights.

Regulatory agencies require that CPV methodologies must be tailored to the process’s unique characteristics. For example, a parameter with data clustered near LOQ (as in the case study) demands a different approach than one with normal variability.

Selecting CPV Tools: Aligning with Data and Risk

The framework emphasizes that CPV tools must be scientifically justified, with selection criteria based on data suitability, risk criticality, and regulatory alignment.

Data Suitability Assessments

Data suitability assessments form the bedrock of effective Continuous Process Verification (CPV) programs, ensuring that monitoring tools align with the statistical and analytical realities of the process. These assessments are not merely technical exercises but strategic activities rooted in regulatory expectations, scientific rigor, and risk management. Below, we explore the three pillars of data suitability—distribution analysis, process capability evaluation, and analytical performance considerations—and their implications for CPV tool selection.

The foundation of any statistical monitoring system lies in understanding the distribution of the data being analyzed. Many traditional tools, such as control charts, assume that data follows a normal (Gaussian) distribution. This assumption underpins the calculation of control limits (e.g., ±3σ) and the interpretation of rule violations. To validate this assumption, manufacturers employ tests such as the Shapiro-Wilk test or Anderson-Darling test, which quantitatively assess normality. Visual tools like Q-Q plots or histograms complement these tests by providing intuitive insights into data skewness, kurtosis, or clustering.

When data deviates significantly from normality—common in parameters with values clustered near detection or quantification limits (e.g., LOQ)—the use of parametric tools like control charts becomes problematic. For instance, a parameter with 95% of its data below the LOQ may exhibit a left-skewed distribution, where the calculated mean and standard deviation are distorted by the analytical method’s noise rather than reflecting true process behavior. In such cases, traditional control charts generate misleading signals, such as Rule 1 violations (±3σ), which flag analytical variability rather than process shifts.

To address non-normal data, manufacturers must transition to non-parametric methods that do not rely on distributional assumptions. Tolerance intervals, which define ranges covering a specified proportion of the population with a given confidence level, are particularly useful for skewed datasets. For example, a 95/99 tolerance interval (95% of data within 99% confidence) can replace ±3σ limits for non-normal data, reducing false positives. Bootstrapping—a resampling technique—offers another alternative, enabling robust estimation of control limits without assuming normality.

Process Capability: Aligning Tools with Inherent Variability

Process capability indices, such as Cp and Cpk, quantify a parameter’s ability to meet specifications relative to its natural variability. A high Cp (>2) indicates that the process variability is small compared to the specification range, often resulting from tight manufacturing controls or robust product designs. While high capability is desirable for quality, it complicates CPV tool selection. For example, a parameter with a Cp of 3 and data clustered near the LOQ will exhibit minimal variability, rendering control charts ineffective. The narrow spread of data means that control limits shrink, increasing the likelihood of false alarms from minor analytical noise.

In such scenarios, traditional SPC tools like control charts lose their utility. Instead, manufacturers should adopt attribute-based monitoring or batch-wise trending. Attribute-based approaches classify results as pass/fail against predefined thresholds (e.g., LOQ breaches), simplifying signal interpretation. Batch-wise trending aggregates data across production lots, identifying shifts over time without overreacting to individual outliers. For instance, a manufacturer with a high-capability dissolution parameter might track the percentage of batches meeting dissolution criteria monthly, rather than plotting individual tablet results.

The FDA’s emphasis on risk-based monitoring further supports this shift. ICH Q9 guidelines encourage manufacturers to prioritize resources for high-risk parameters, allowing low-risk, high-capability parameters to be monitored with simpler tools. This approach reduces administrative burden while maintaining compliance.

Analytical Performance: Decoupling Noise from Process Signals

Parameters operating near analytical limits of detection (LOD) or quantification (LOQ) present unique challenges. At these extremes, measurement systems contribute significant variability, often overshadowing true process signals. For example, a purity assay with an LOQ of 0.1% may report values as “<0.1%” for 98% of batches, creating a dataset dominated by the analytical method’s imprecision. In such cases, failing to decouple analytical variability from process performance leads to misguided investigations and wasted resources.

To address this, manufacturers must isolate analytical variability through dedicated method monitoring programs. This involves:

- Analytical Method Validation: Rigorous characterization of precision, accuracy, and detection capabilities (e.g., determining the Practical Quantitation Limit, or PQL, which reflects real-world method performance).

- Separate Trending: Implementing control charts or capability analyses for the analytical method itself (e.g., monitoring LOQ stability across batches).

- Threshold-Based Alerts: Replacing statistical rules with binary triggers (e.g., investigating only results above LOQ).

For example, a manufacturer analyzing residual solvents near the LOQ might use detection capability indices to set action limits. If the analytical method’s variability (e.g., ±0.02% at LOQ) exceeds the process variability, threshold alerts focused on detecting values above 0.1% + 3σ_analytical would provide more meaningful signals than traditional control charts.

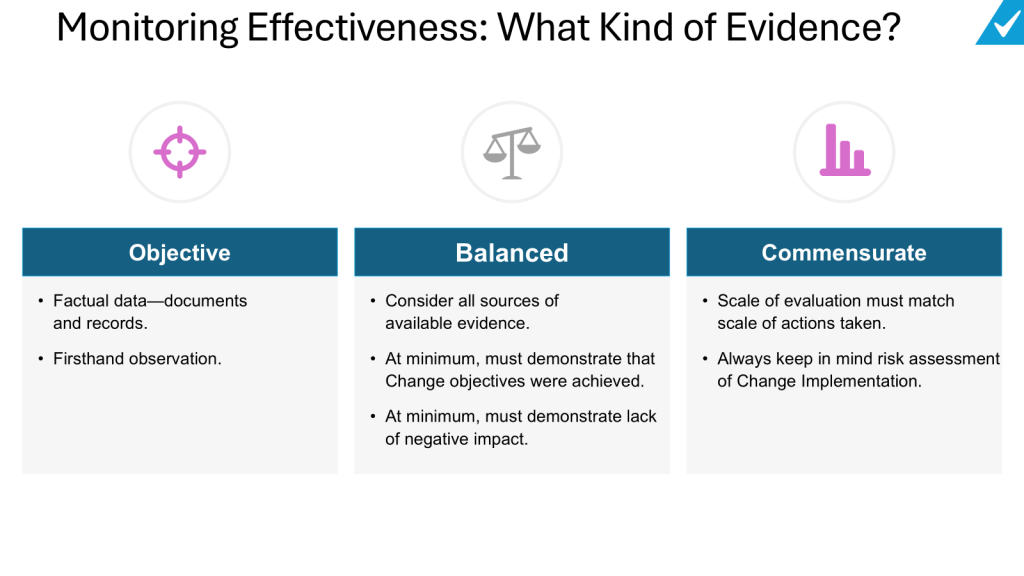

Integration with Regulatory Expectations

Regulatory agencies, including the FDA and EMA, mandate that CPV methodologies be “scientifically sound” and “statistically valid” (FDA 2011 Guidance). This requires documented justification for tool selection, including:

- Normality Testing: Evidence that data distribution aligns with tool assumptions (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk test results).

- Capability Analysis: Cp/Cpk values demonstrating the rationale for simplified monitoring.

- Analytical Validation Data: Method performance metrics justifying decoupling strategies.

A 2024 FDA warning letter highlighted the consequences of neglecting these steps. A firm using control charts for non-normal dissolution data received a 483 observation for lacking statistical rationale, underscoring the need for rigor in data suitability assessments.

Case Study Application:

A manufacturer monitoring a CQA with 98% of data below LOQ initially used control charts, triggering frequent Rule 1 violations (±3σ). These violations reflected analytical noise, not process shifts. Transitioning to threshold-based alerts (investigating only LOQ breaches) reduced false positives by 72% while maintaining compliance.

Risk-Based Tool Selection

The ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management (QRM) framework provides a structured methodology for identifying, assessing, and controlling risks to pharmaceutical product quality, with a strong emphasis on aligning tool selection with the parameter’s impact on patient safety and product efficacy. Central to this approach is the principle that the rigor of risk management activities—including the selection of tools—should be proportionate to the criticality of the parameter under evaluation. This ensures resources are allocated efficiently, focusing on high-impact risks while avoiding overburdening low-risk areas.

Prioritizing Tools Through the Lens of Risk Impact

The ICH Q9 framework categorizes risks based on their potential to compromise product quality, guided by factors such as severity, detectability, and probability. Parameters with a direct impact on critical quality attributes (CQAs)—such as potency, purity, or sterility—are classified as high-risk and demand robust analytical tools. Conversely, parameters with minimal impact may require simpler methods. For example:

- High-Impact Parameters: Use Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) or Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) to dissect failure modes, root causes, and mitigation strategies.

- Medium-Impact Parameters: Apply a tool such as a PHA.

- Low-Impact Parameters: Utilize checklists or flowcharts for basic risk identification.

This tiered approach ensures that the complexity of the tool matches the parameter’s risk profile.

- Importance: The parameter’s criticality to patient safety or product efficacy.

- Complexity: The interdependencies of the system or process being assessed.

- Uncertainty: Gaps in knowledge about the parameter’s behavior or controls.

For instance, a high-purity active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) with narrow specification limits (high importance) and variable raw material inputs (high complexity) would necessitate FMEA to map failure modes across the supply chain. In contrast, a non-critical excipient with stable sourcing (low uncertainty) might only require a simplified risk ranking matrix.

Implementing a Risk-Based Approach

1. Assess Parameter Criticality

Begin by categorizing parameters based on their impact on CQAs, as defined during Stage 1 (Process Design) of the FDA’s validation lifecycle. Parameters are classified as:

- Critical: Directly affecting safety/efficacy

- Key: Influencing quality but not directly linked to safety

- Non-Critical: No measurable impact on quality

This classification informs the depth of risk assessment and tool selection.

2. Select Tools Using the ICU Framework

- Importance-Driven Tools: High-importance parameters warrant tools that quantify risk severity and detectability. FMEA is ideal for linking failure modes to patient harm, while Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts monitor real-time variability.

- Complexity-Driven Tools: For multi-step processes (e.g., bioreactor operations), HACCP identifies critical control points, while Ishikawa diagrams map cause-effect relationships.

- Uncertainty-Driven Tools: Parameters with limited historical data (e.g., novel drug formulations) benefit from Bayesian statistical models or Monte Carlo simulations to address knowledge gaps.

3. Document and Justify Tool Selection

Regulatory agencies require documented rationale for tool choices. For example, a firm using FMEA for a high-risk sterilization process must reference its ability to evaluate worst-case scenarios and prioritize mitigations. This documentation is typically embedded in Quality Risk Management (QRM) Plans or validation protocols.

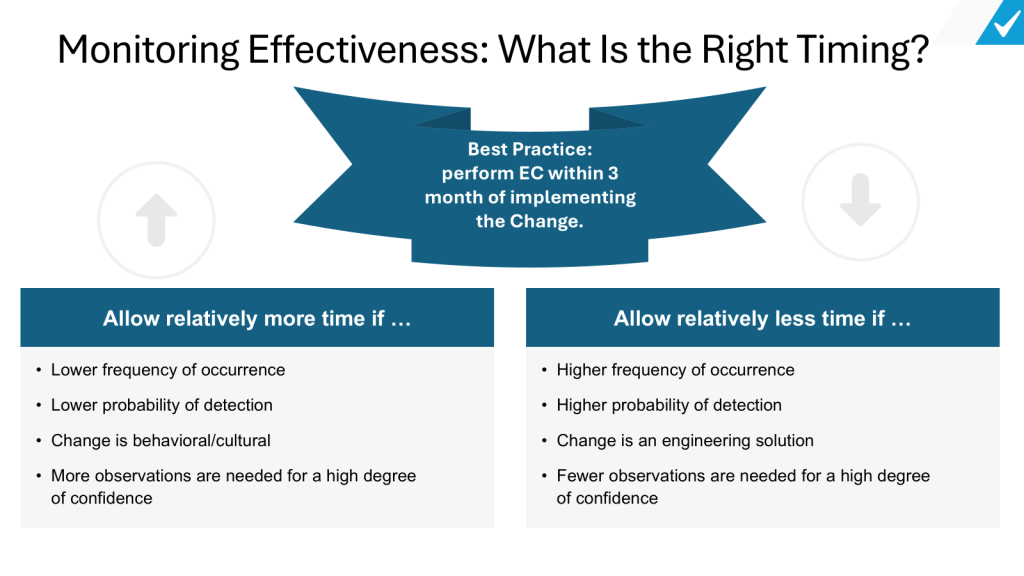

Integration with Living Risk Assessments

Living risk assessments are dynamic, evolving documents that reflect real-time process knowledge and data. Unlike static, ad-hoc assessments, they are continually updated through:

1. Ongoing Data Integration

Data from Continual Process Verification (CPV)—such as trend analyses of CPPs/CQAs—feeds directly into living risk assessments. For example, shifts in fermentation yield detected via SPC charts trigger updates to bioreactor risk profiles, prompting tool adjustments (e.g., upgrading from checklists to FMEA).

2. Periodic Review Cycles

Living assessments undergo scheduled reviews (e.g., biannually) and event-driven updates (e.g., post-deviation). A QRM Master Plan, as outlined in ICH Q9(R1), orchestrates these reviews by mapping assessment frequencies to parameter criticality. High-impact parameters may be reviewed quarterly, while low-impact ones are assessed annually.

3. Cross-Functional Collaboration

Quality, manufacturing, and regulatory teams collaborate to interpret CPV data and update risk controls. For instance, a rise in particulate matter in vials (detected via CPV) prompts a joint review of filling line risk assessments, potentially revising tooling from HACCP to FMEA to address newly identified failure modes.

Regulatory Expectations and Compliance

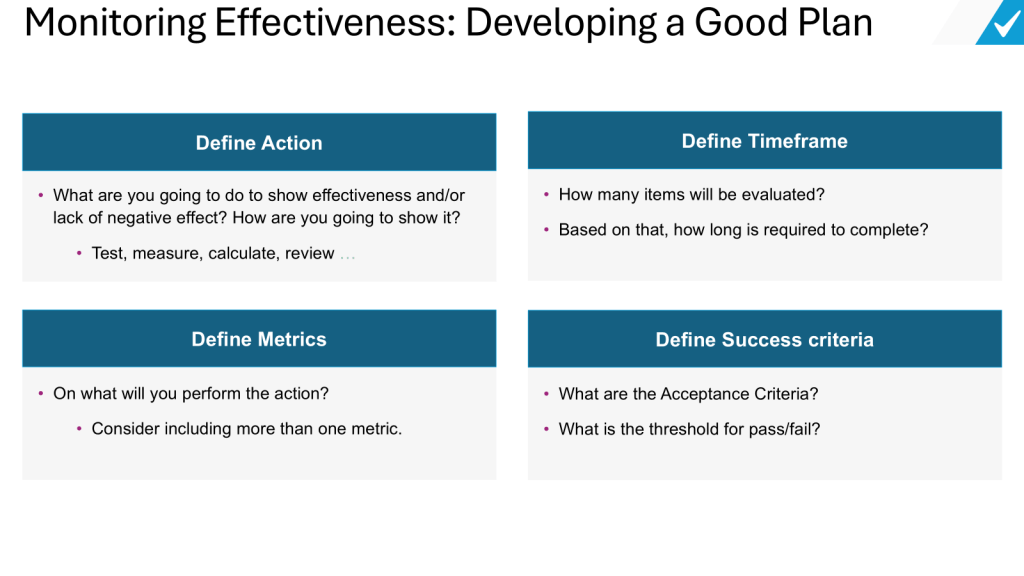

Regulatory agencies requires documented justification for CPV tool selection, emphasizing:

- Protocol Preapproval: CPV plans must be submitted during Stage 2, detailing tool selection criteria.

- Change Control: Transitions between tools (e.g., SPC → thresholds) require risk assessments and documentation.

- Training: Staff must be proficient in both traditional (e.g., Shewhart charts) and modern tools (e.g., AI).

A 2024 FDA warning letter cited a firm for using control charts on non-normal data without validation, underscoring the consequences of poor tool alignment.

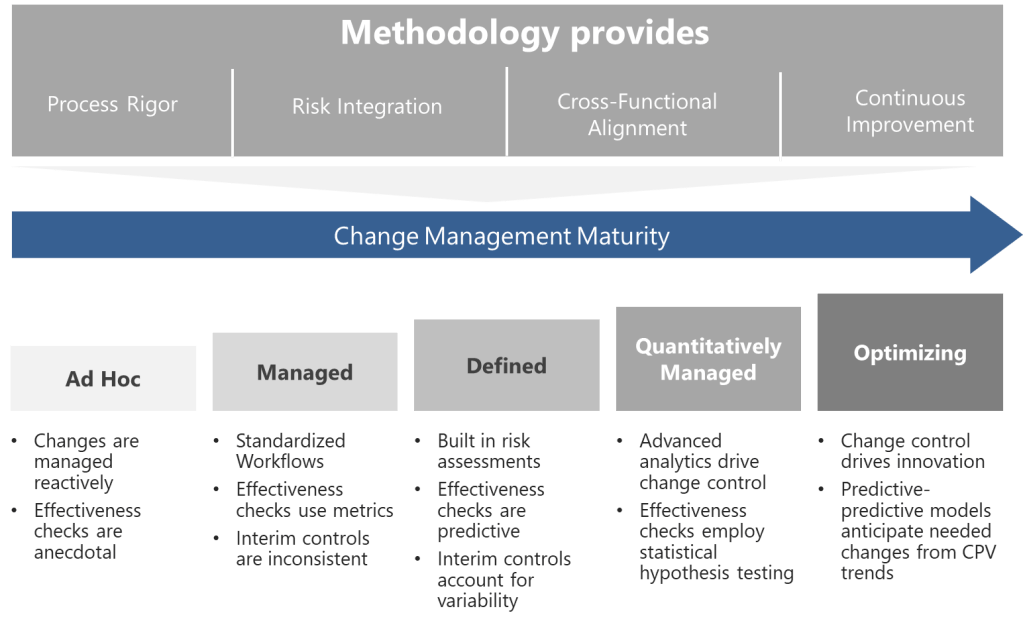

A Framework for Adaptive Excellence

The FDA’s CPV framework is not prescriptive but principles-based, allowing flexibility in methodology and tool selection. Successful implementation hinges on:

- Science-Driven Decisions: Align tools with data characteristics and process capability.

- Risk-Based Prioritization: Focus resources on high-impact parameters.

- Regulatory Agility: Justify tool choices through documented risk assessments and lifecycle data.

CPV is a living system that must evolve alongside processes, leveraging tools that balance compliance with operational pragmatism. By anchoring decisions in the FDA’s lifecycle approach, manufacturers can transform CPV from a regulatory obligation into a strategic asset for quality excellence.