Pharmaceutical compliance is experiencing a tectonic shift, and nowhere is that more clear than in the looming overhaul of EU GMP Annex 11. Most quality leaders have been laser-focused on the revised demands for electronic signatures, access management, or supplier oversight—as I’ve detailed in my previous deep analyses, but few realize that Section 10: Handling of Data is the sleeping volcano in the draft. It is here that the revised Annex 11 transforms data handling controls from “do your best and patch with SOPs” into an auditable, digital, risk-based discipline shaped by technological change.

This isn’t about stocking up your data archive or flipping the “audit trail” switch. This is about putting every point of data entry, transfer, migration, and security under the microscope—and making their control, verification, and risk mitigation the default, not the exception. If, until now, your team has managed GMP data with a cocktail of trust, periodic spot checks, and a healthy dose of hope, you are about to discover just how high the bar has been raised.

The Heart of Section 10: Every Data Touchpoint Is Critical

Section 10, as rewritten in the draft Annex 11, isn’t long, but it is dense. Its brevity belies the workload it creates: a mandate for systematizing, validating, and documenting every critical movement or entry of GMP-relevant data. The section is split into four thematic requirements, each of which deserves careful analysis:

- Input verification—requiring plausibility checks for all manual entry of critical data,

- Data transfer—enforcing validated electronic interfaces and exceptional controls for any manual transcription,

- Data migration—demanding that every one-off or routine migration goes through a controlled, validated process,

- Encryption—making secure storage and movement of critical data a risk-based expectation, not an afterthought.

Understanding these not as checkboxes but as an interconnected risk-control philosophy is the only way to achieve robust compliance—and to survive inspection without scrambling for a “procedural explanation” for each data error found.

Input Verification: Automating the Frontline Defense

The End of “Operator Skill” as a Compliance Pillar

Human error, for as long as there have been batch records and lab notebooks, has been a known compliance risk. Before electronic records, the answer was redundancy: a second set of eyes, a periodic QC review, or—let’s be realistic—a quick initial on a form the day before an audit. But in the age of digital systems, Section 10.1 recognizes the simple truth: where technology can prevent senseless or dangerous entries, it must.

Manual entry of critical data—think product counts, analytical results, process parameters—is now subject to real-time, system-enforced plausibility checks. Gone are the days when outlandish numbers in a yield calculation raises no flag, or when an analyst logs a temperature outside any physically possible range with little more than a raised eyebrow. Section 10 demands that every critical data field is bounded by logic—ranges, patterns, value consistency checks—and that nonsensical entries are not just flagged but, ideally, rejected automatically.

Any field that is critical to product quality or patient safety must be controlled at the entry point by automated means. If such logic is technically feasible but not deployed, expect intensive regulatory scrutiny—and be prepared to defend, in writing, why it isn’t in place.

Designing Plausibility Controls: Making Them Work

What does this mean on a practical level? It means scoping your process maps and digitized workflows to inventory every manual input touching GMP outcomes. For each, you need to:

- Establish plausible ranges and patterns based on historical data, scientific rationale, and risk analysis.

- Program system logic to enforce these boundaries, including mandatory explanatory overrides for any values outside “normal.”

- Ensure every override is logged, investigated, and trended—because “frequent overrides” typically signal either badly set limits or a process slipping out of control.

But it’s not just numeric entries. Selectable options, free-text assessments, and uploads of evidence (e.g., images or files) must also be checked for logic and completeness, and mechanisms must exist to prevent accidental omissions or nonsensical entries (like uploading the wrong batch report for a product lot).

These expectations put pressure on system design teams and user interface developers, but they also fundamentally change the culture: from one where error detection is post hoc and personal, to one where error prevention is systemic and algorithmic.

Data Transfer: Validated Interfaces as the Foundation

Automated Data Flows, Not “Swivel Chair Integration”

The next Section 10 pillar wipes out the old “good enough” culture of manually keying critical data between systems—a common practice all the way up to the present day, despite decades of technical options to network devices, integrate systems, and use direct data feeds.

In this new paradigm, critical data must be transferred between systems electronically whenever possible. That means, for example, that:

- Laboratory instruments should push their results to the LIMS automatically, not rely on an analyst to retype them.

- The MES should transmit batch data to ERP systems for release decisions without recourse to copy-pasting or printout scanning.

- Environmental monitoring systems should use validated data feeds into digital reports, not rely on handwritten transcriptions or spreadsheet imports.

Where technology blocks this approach—due to legacy equipment, bespoke protocols, or prohibitive costs—manual transfer is only justifiable as an explicitly assessed and mitigated risk. In those rare cases, organizations must implement secondary controls: independent verification by a second person, pre- and post-transfer checks, and logging of every step and confirmation.

What does a validated interface mean in this context? Not just that two systems can “talk,” but that the transfer is:

- Complete (no dropped or duplicated records)

- Accurate (no transformation errors or field misalignments)

- Secure (with no risk of tampering or interception)

Every one of these must be tested at system qualification (OQ/PQ) and periodically revalidated if either end of the interface changes. Error conditions (such as data out of expected range, failed transfers, or discrepancies) must be logged, flagged to the user, and if possible, halt the associated GMP process until resolved.

Practical Hurdles—and Why They’re No Excuse

Organizations will protest: not every workflow can be harmonized, and some labyrinthine legacy systems lack the APIs or connectivity for automation. The response is clear: you can do manual transfer only when you’ve mapped, justified, and mitigated the added risk. This risk assessment and control strategy will be expected, and if auditors spot critical data being handed off by paper (including the batch record) or spreadsheet without robust double verification, you’ll have a finding that’s impossible to “train away.”

Remember, Annex 11’s philosophy flows from data integrity risk, not comfort or habit. In the new digital reality, technically possible is the compliance baseline.

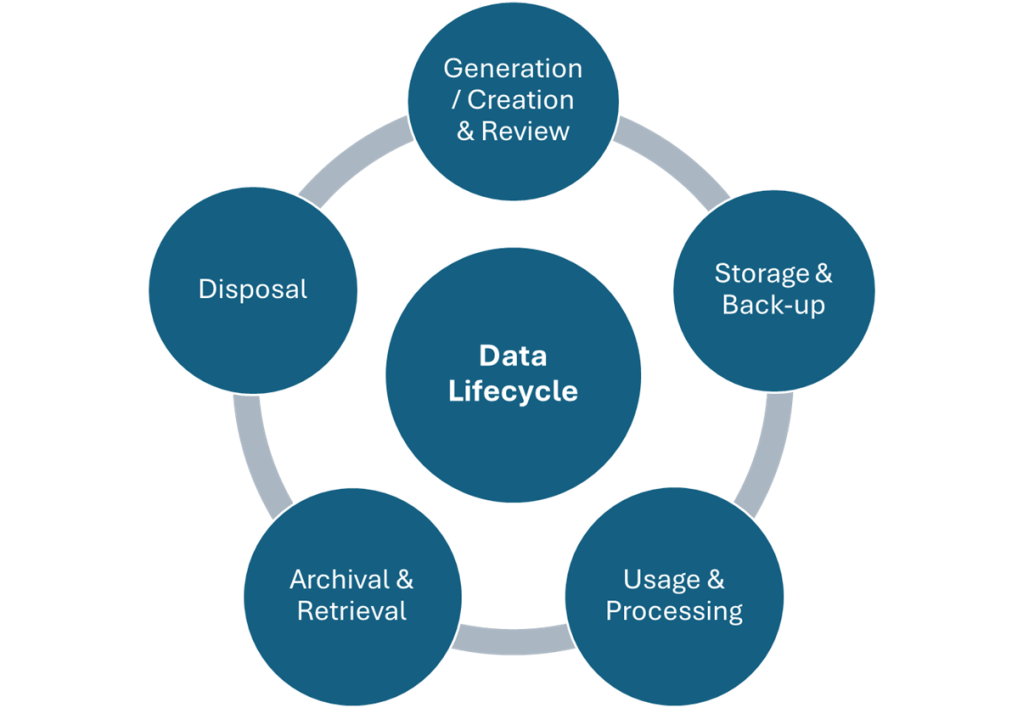

Data Migration: Control, Validation, and Traceability

Migration Upgrades Are Compliance Projects, Not IT Favors

Section 10.3 brings overdue clarity to a part of compliance historically left to “IT shops” rather than Quality or data governance leads: migrations. In recent years, as cloud moves and system upgrades have exploded, so have the risks. Data gaps, incomplete mapping, field mismatches, and “it worked in test but not in prod” errors lurk in every migration, and their impact is enormous—lost batch records, orphaned critical information, and products released with documentation that simply vanished after a system reboot.

Annex 11 lays down a clear gauntlet: all data migrations must be planned, risk-assessed, and validated. Both the sending and receiving platforms must be evaluated for data constraints, and the migration process itself is subject to the same quality rigor as any new computerized system implementation.

This requires a full lifecycle approach:

- Pre-migration planning to document field mapping, data types, format and allowable value reconciliations, and expected record counts.

- Controlled execution with logs of each action, anomalies, and troubleshooting steps.

- Post-migration verification—not just a “looks ok” sample, but a full reconciliation of batch counts, search for missing or duplicated records, and (where practical) data integrity spot checks.

- Formal sign-off, with electronic evidence and supporting risk assessment, that the migration did not introduce errors, losses, or uncontrolled transformations.

Validating the Entire Chain, Not Just the Output

Annex 11’s approach is process-oriented. You can’t simply “prove a few outputs match”; you must show that the process as executed controlled, logged, and safeguarded every record. If source data was garbage, destination data will be worse—so validation includes both the “what” and the “how.” Don’t forget to document how you’ll highlight or remediate mismatched or orphaned records for future investigation or reprocessing; missing this step is a quality and regulatory land mine.

It’s no longer acceptable to treat migration as a purely technical exercise. Every migration is a compliance event. If you can’t show the system’s record—start-to-finish—of how, by whom, when, and under what procedural/corrective control migrations have been performed, you are vulnerable on every product released or batch referencing that data.

Encryption: Securing Data as a Business and Regulatory Mandate

Beyond “Defense in Depth” to a Compliance Expectation

Historically, data security and encryption were IT problems, and the GMP justification for employing them was often little stronger than “everyone else is doing it.” The revised Section 10 throws that era in the trash bin. Encryption is now a risk-based compliance requirement for storage and transfer of critical GMP data. If you don’t use strong encryption “where applicable,” you’d better have a risk assessment ready that shows why the threat is minimal or the technical/operational risk of encryption is greater than the gain.

This requirement is equally relevant whether you’re holding batch record files, digital signatures, process parameter archives, raw QC data, or product release records. Security compromises aren’t just a hacking story; they’re a data integrity, fraud prevention, and business continuity story. In the new regulatory mindset, unencrypted critical data is always suspicious. This is doubly so when the data moves through cloud services, outsourced IT, or is ever accessible outside the organization’s perimeter.

Implementing and Maintaining Encryption: Avoiding Hollow Controls

To comply, you need to specify and control:

- Encryption standards (e.g., minimum AES-256 for rest and transit)

- Robust key management (with access control, periodic audits, and revocation/logging routines)

- Documentation for every location and method where data is or isn’t encrypted, with reference to risk assessments

- Procedures for regularly verifying encryption status and responding to incidents or suspected compromises

Regulators will likely want to see not only system specifications but also periodic tests, audit trails of encryption/decryption, and readouts from recent patch cycles or vulnerability scans proving encryption hasn’t been silently “turned off” or configured improperly.

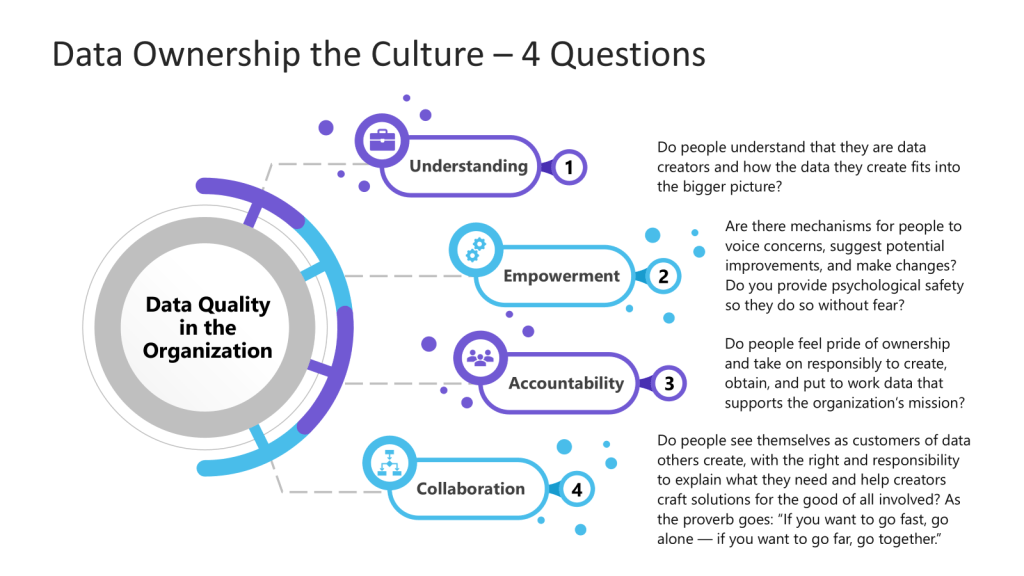

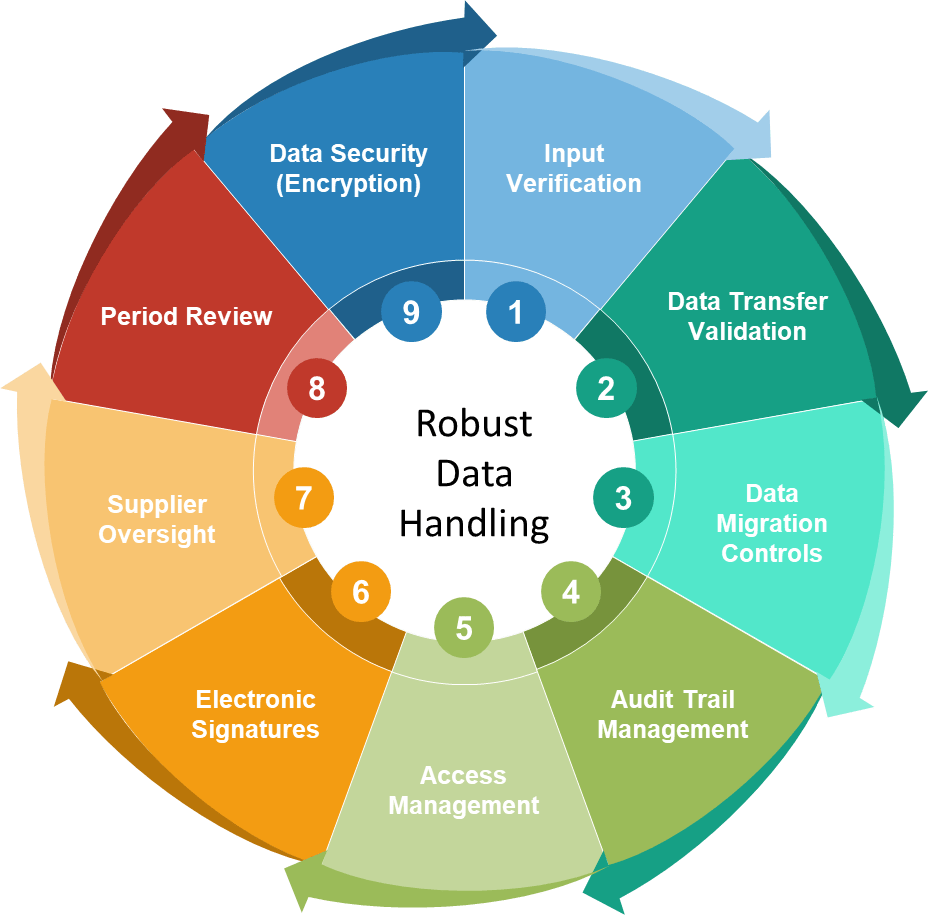

Section 10 Is the Hub of the Data Integrity Wheel

Section 10 cannot be treated in isolation. It underpins and is fed by virtually every other control in the GMP computerized system ecosystem.

- Input controls support audit trails: If data can be entered erroneously or fraudulently, the best audit trail is just a record of error.

- Validated transfers prevent downstream chaos: If system A and system B don’t transfer reliably, everything “downstream” is compromised.

- Migrations touch batch continuity and product release: If you lose or misplace records, your recall and investigation responses are instantly impaired.

- Encryption protects change control and deviation closure: If sensitive data is exposed, audit trails and signature controls can’t protect you from the consequences.

Risk-Based Implementation: From Doctrine to Daily Practice

The draft’s biggest strength is its honest embrace of risk-based thinking. Every expectation in Section 10 is to be scaled by impact to product quality and patient safety. You can—and must—document decisions for why a given control is (or is not) necessary for every data touchpoint in your process universe.

That means your risk assessment does more than check a box. For every GMP data field, every transfer, every planned or surprise migration, every storage endpoint, you need to:

- Identify every way the data could be made inaccurate, incomplete, unavailable, or stolen.

- Define controls appropriate both to the criticality of the data and the likelihood and detectability of error or compromise.

- Test and document both normal and failure scenarios—because what matters in a recall, investigation, or regulatory challenge is what happens when things go wrong, not just when they go right.

ALCOA+ is codified by these risk processes: accuracy via plausibility checks, completeness via transfer validation, longevity via robust migration and storage; contemporaneity and endurability via encryption and audit linkage.

Handling of Data vs. Previous Guidance and Global Norms

While much of this seems “good practice,” make no mistake: the regulatory expectations have fundamentally changed. In 2011, Annex 11 was silent on specifics, and 21 CFR Part 11 relied on broad “input checks” and an expectation that organizations would design controls relative to what was reasonable at the time.

Now:

- Electronic input plausibility is not just a “should” but a “must”—if your system can automate it, you must.

- Manual transfer is justified, not assumed; all manual steps must have procedural/methodological reinforcement and evidence logs.

- Migration is a qualification event. The entire lifecycle, not just the output, must be documented, trended, and reviewed.

- Encryption is an expectation, not a best effort. The risk burden now falls on you to prove why it isn’t needed, not why it is.

- Responsibility is on the MAH/manufacturer, not the vendor, IT, or “business owner.” You outsource activity, not liability.

This matches, in setting, recent FDA guidance via Computer Software Assurance (CSA), GAMP 5’s digital risk lifecycle, and every modern data privacy regulation. The difference is that, starting with the new Annex 11, these approaches are not “suggested”—they are codified.

Real-Life Scenarios: Application of Section 10

Imagine a high-speed packaging line. The operator enters the number of rejected vials per shift. In the old regime, the operator could mistype “80” as “800” or enter a negative number during a hasty correction. With section 10 in force, the system simply will not permit it—90% confidence that any such error will be caught before it mars the official record.

Now think about laboratory results—analysts transferring HPLC data into the LIMS manually. Every entry runs a risk of decimal misplacement or sample ID mismatch. Annex 11 now demands full instrument-to-LIMS interfacing (where feasible), and when not, a double verification protocol meticulously executed, logged, and reviewed.

On the migration front, consider upgrading your document management system. The stakes: decades of batch release records. In 2019, you might have planned a database export, a few spot checks, and post-migration validation of “high value” documents. Under the new Annex 11, you require a documented mapping of every critical field, technical and process reconciliation, error reporting, and lasting evidence for defensibility two or ten years from now.

Encryption is now expected as a default. Cloud-hosted data with no encryption? Prepare to be asked why, and to defend your choice with up-to-date, context-specific risk assessments—not hand-waving.

Bringing Section 10 to Life: Steps for Implementation

A successful strategy for aligning to Annex 11 Section 10 begins with an exhaustive mapping of all critical data touchpoints and their methods of entry, transfer, and storage. This is a multidisciplinary process, requiring cooperation among quality, IT, operations, and compliance teams.

For each critical data field or process, define:

- The party responsible for its entry and management

- The system’s capability for plausibility checking, range enforcement, and error prevention;

- Mechanisms to block or correct entry outside expected norms

- Methods of data handoff and transfer between systems, with documentation of integration or a procedural justification for unavoidable manual steps

- Protocols and evidence logs for validation of both routine transfers and one-off (migration) events

For all manual data handling that remains, create detailed, risk-based procedures for independent verification and trending review. For data migration, walk through an end-to-end lifecycle—pre-migration risk mapping, execution protocols, post-migration review, discrepancy handling, and archiving of all planning/validation evidence.

For storage and transfer, produce a risk matrix for where and how critical data is held, updated, and moved, and deploy encryption accordingly. Document both technical standards and the process for periodic review and incident response.

Quality management is not the sole owner; business leads, system admins, and IT architects must be brought to the table. For every major change, tie change control procedures to a Section 10 review—any new process, upgrade, or integration comes back to data handling risk, with a closing check for automation and procedural compliance.

Regulatory Impact and Inspection Strategy

Regulatory expectations around data integrity are not only becoming more stringent—they are also far more precise and actionable than in the past. Inspectors now arrive prepared and trained to probe deeply into what’s called “data provenance”: that is, the complete, traceable life story of every critical data point. It’s no longer sufficient to show where a value appears in a final batch record or report; regulators want to see how that data originated, through which systems and interfaces it was transferred, how each entry or modification was verified, and exactly what controls were in place (or not in place) at each step.

Gone are the days when, if questioned about persistent risks like error-prone manual transcription, a company could deflect with, “that’s how we’ve always done it.” Now, inspectors expect detailed explanations and justifications for every manual, non-automated, or non-encrypted data entry or transfer. They will require you to produce not just policies but actual logs, complete audit trails, electronic signature evidence where required, and documented decision-making within your risk assessments for every process step that isn’t fully controlled by technology.

In practical terms, this means you must be able to reconstruct and defend the exact conditions and controls present at every point data is created, handled, moved, or modified. If a process relies on a workaround, a manual step, or an unvalidated migration, you will need transparent evidence that risks were understood, assessed, and mitigated—not simply asserted away.

The implications are profound: mastering Section 10 isn’t just about satisfying the regulator. Robust, risk-based data handling is fundamental to your operation’s resilience—improving traceability, minimizing costly errors or data loss, ensuring you can withstand disruption, and enabling true digital transformation across your business. Leaders who excel here will find that their compliance posture translates into real business value, competitive differentiation, and lasting operational stability.

The Bigger Picture: Section 10 as Industry Roadmap

What’s clear is this: Section 10 eliminates the excuses that have long made “data handling risk” a tolerated, if regrettable, feature of pharmaceutical compliance. It replaces them with a pathway for digital, risk-based, and auditable control culture. This is not just for global pharma behemoths—cloud-native startups, generics manufacturers, and even virtual companies reliant on CDMOs must take note. The same expectations now apply to every regulated data touchpoint, wherever in the supply chain or manufacturing lifecycle it lies.

Bringing your controls into compliance with Section 10 is a strategic imperative in 2025 and beyond. Those who move fastest will spend less time and money on post-inspection remediation, operate more efficiently, and have a defensible record for every outcome.

| Requirement Area | Annex 11 (2011) | Draft Annex 11 Section 10 (2025) | 21 CFR Part 11 | GAMP 5 / Best Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input verification | General expectation, not defined | Mandatory for critical manual entry; system logic and boundaries | “Input checks” required, methods not specified | Risk-based, ideally automated |

| Data transfer | Manual allowed, interface preferred | Validated interfaces wherever possible; strict controls for manual | Implicit through system interface requirements | Automated transfer is the baseline, double checked for manual |

| Manual transcription | Allowed, requires review | Only justified exceptions; robust secondary verification & documentation | Not directly mentioned | Two-person verification, periodic audit and trending |

| Data migration | Mentioned, not detailed | Must be planned, risk-assessed, validated, and be fully auditable | Implied via system lifecycle controls | Full protocol: mapping, logs, verification, and discrepancy handling |

| Encryption | Not referenced | Mandated for critical data; exceptions need documented, defensible risk | Recommended, not strictly required | Default for sensitive data; standard in cloud, backup, and distributed setups |

| Audit trail for handling | Implied via system change auditing | All data moves and handling steps linked/logged in audit trail | Required for modifications/rest/correction | Integrated with system actions, trended for error and compliance |

| Manual exceptions | Not formally addressed | Must be justified and mitigated; always subject to periodic review | Not directly stated | Exception management, always with trending, review, and CAPA |

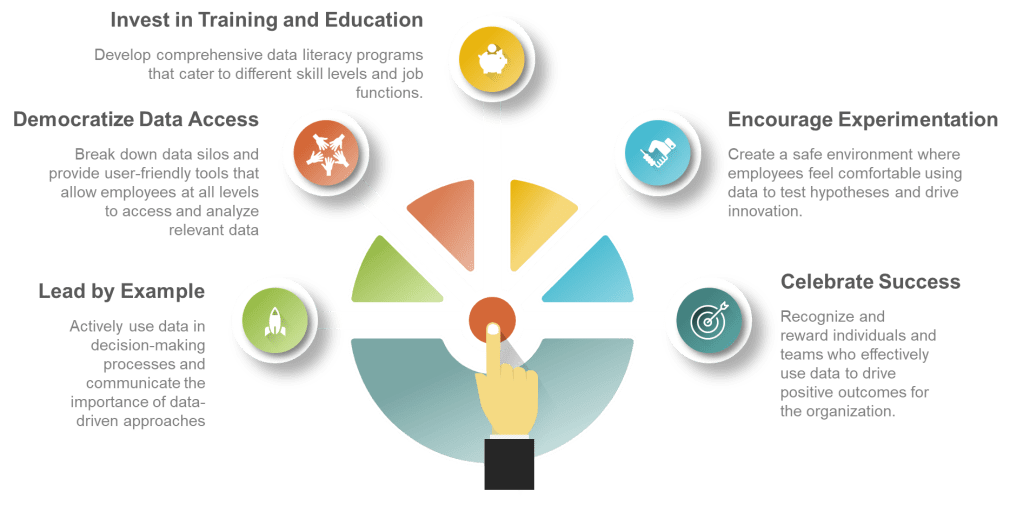

Handling of Data as Quality Culture, Not Just IT Control

Section 10 in the draft Annex 11 is nothing less than the codification of real data integrity for the digitalized era. It lays out a field guide for what true GMP data governance looks like—not in the clouds of intention, but in the minutiae of everyday operation. Whether you’re designing a new MES integration, cleaning up the residual technical debt of manual record transfer, or planning the next system migration, take heed: how you handle data when no one’s watching is the new standard of excellence in pharmaceutical quality.

As always, the organizations that embrace these requirements as opportunities—not just regulatory burdens—will build a culture, a system, and a supply chain that are robust, efficient, and genuinely defensible.