The decisions we make are often complex and uncertain. A good decision-making process better is critical to success – knowing how we make decisions, and how to confirm we are making good decisions – allows us to bring quality to our decisions. To do this we need to understand what a quality decision looks like and how to obtain it.

There is no universal best process or set of steps to follow in making good decisions. However, any good decision process needs to have the idea of decision-quality as the measurable destination.

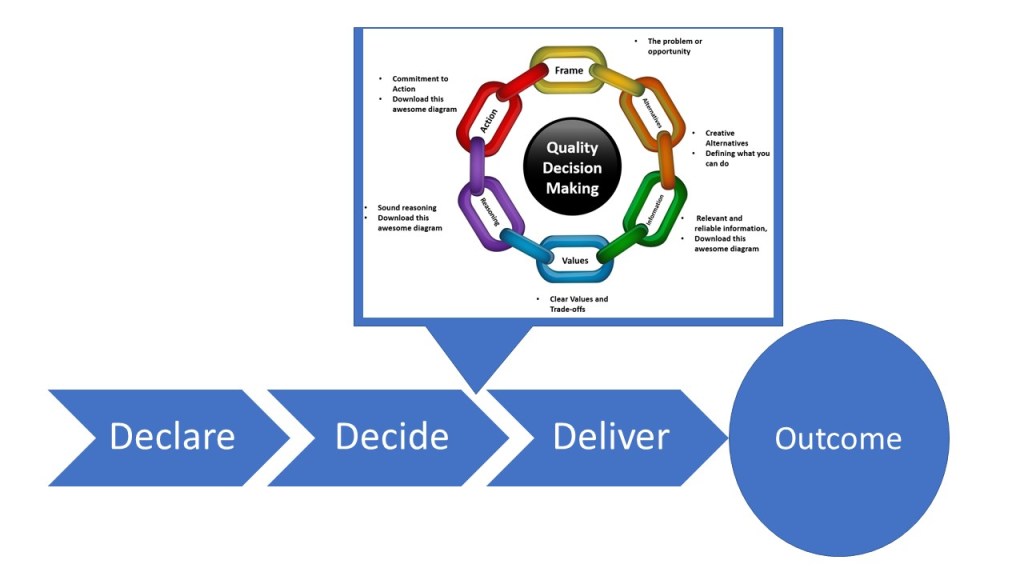

Decisions do not come ready to be made. They must be shaped starting by declaring what the decision you that must be made. All decisions have one thing in common – the best choice creates the best possibility of what you truly want. To find that best choice, you need decision-quality and you must recognize it as the destination when you get there. You cannot reach a good decision, achieve decision-quality, if you are unable to visualize or describe it. Nor can you say you have accomplished it, if you cannot recognize it when it is achieved.

What makes a Good Decision?

The six requirements for a good decision are: (1) an appropriate frame, (2) creative alternatives, (3) relevant and reliable information, (4) clear values and trade-offs, (5) sound reasoning, and (6) commitment to action. To judge the quality of any decision before you act, each requirement must be met and addressed with quality. I like representing it as a chain, because a decision is no better than the weakest link.

The frame specifies the problem or opportunity you are tackling, asking what is to be decided. It has three parts: purpose in making the decision; scope of what will be included and left out; and your perspective including your point of view, how you want to approach the decision, what conversations will be needed, and with whom. Agreement on framing is essential, especially when more than one party is involved in decision making. What is important is to find the frame that is most appropriate for the situation. If you get the frame wrong, you will be solving the wrong problem or not dealing with the opportunity in the correct way.

The next three links are: alternatives – defining what you can do; information – capturing what you know and believe (but cannot control), and values – representing what you want and hope to achieve. These are the basis of the decision and are combined using sound reasoning, which guides you to the best choice (the alternative that gets you the most of what you want and in light of what you know). With sound reasoning, you reach clarity of intention and are ready for the final element – commitment to action.

Asking: “What is the decision I should be making?” is not a simple question. Furthermore, asking the question “On what decision should I be focusing?” is particularly challenging. It is a question, however, that is important to be asked, because you must know what decision you are making. It defines the range within which you have creative and compelling alternatives. It defines constraints. It defines what is possible. Many organizations fail to create a rich set of alternatives and simply debate whether to accept or reject a proposal. The problem with this approach is that people frequently latch on to ideas that are easily accessible, familiar or aligned directly with their experiences.

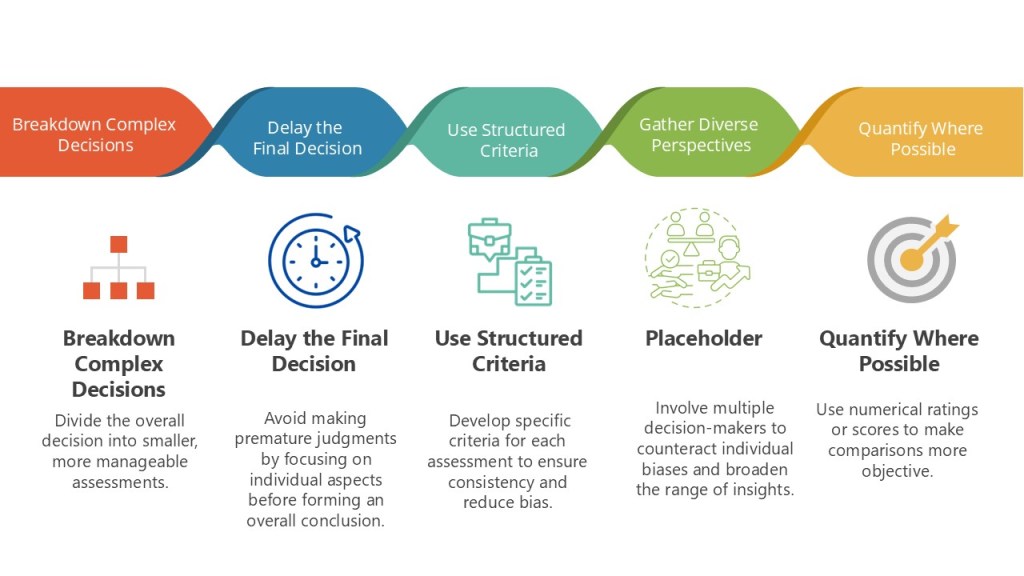

Exploring alternatives is a combination of analysis, rigor, technology and judgement. This is about the past and present – requiring additional judgement to anticipate future consequences. What we know about the future is uncertain and therefore needs to be described with possibilities and probabilities. Questions like: “What might happen?” and “How likely is it to happen?” are difficult and often compound. To produce reliable judgements about future outcomes and probabilities you must gather facts, study trends and interview experts while avoiding distortions from biases and decision traps. When one alternative provides everything desired, the choice among alternatives is not difficult. Trade-offs must be made when alternatives do not provide everything desired. You must then decide how much of one value you are willing to give up to receive more of another.

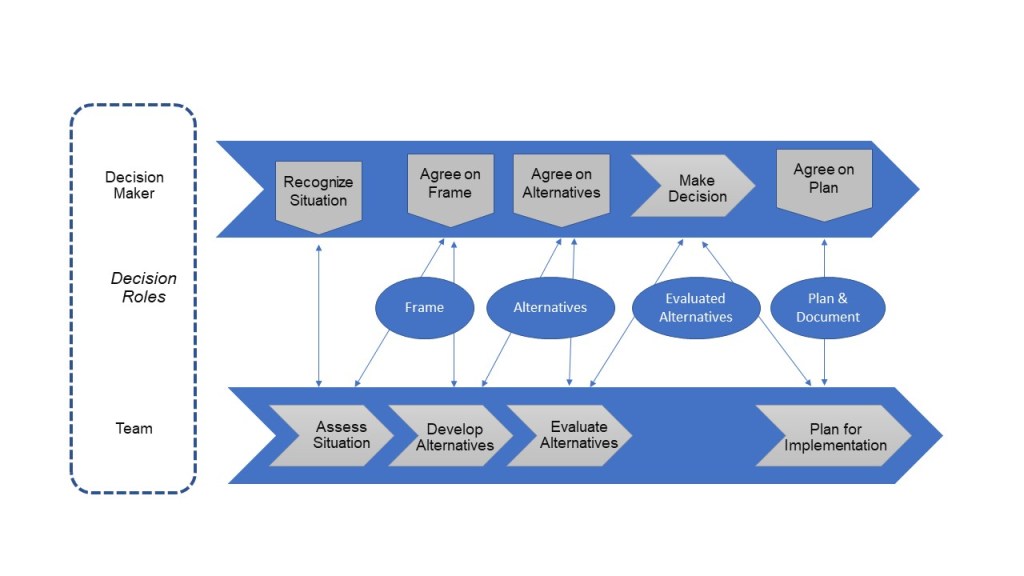

Commitment to action is reached by involving the right people in the decision efforts. The right people must include individuals who have the authority and resources to commit to the decision and to make it stick (the decision makers) and those who will be asked to execute the decided-upon actions (the implementers). Decision makers are frequently not the implementers and much of a decision’s value can be lost in the handoff to implementers. It is important to always consider the resource requirements and challenges for implementation.

These six requirements of decision-quality can be used to judge the quality of the decision at the time it is made. There is no need to wait six months or six years to assess its outcome before declaring the decision’s quality. By meeting the six requirements you know at the time of the decision you made a high-quality choice. You cannot simply say: “I did all the right steps.” You have got to be able to judge the decision itself, not just how you got to that decision. When you ask, “How good is this decision if we make it now?” the answer must be a very big part of your process. The piece missing in the process just may be in the material and the research and that is a piece that must go right.

Decision-quality is all about reducing comfort zone bias – when people do what they know how to do, rather than what is needed to make a strong, high-quality decision. You overcome the comfort zone bias by figuring out where there are gaps. Let us say the gap is with alternatives. Your process then becomes primarily a creative process to generate alternatives instead of gathering a great deal more data. Maybe we are awash in a sea of information, but we just have not done the reasoning and modelling and understanding of the consequences. This becomes more of an analytical effort. The specific gaps define where you should put your attention to improve the quality of the decision.

Leadership needs to have clearly defined decision rights and understand that the role of leadership is assembling the right people to make quality decisions. Once you know how to recognize digital quality, you need an effective and efficient process to get there and that process involves many things including structured interactions between decision maker and decision staff, remembering that productive discussions result when multiple parties are involved in the decision process and difference in judgement are present.

Beware Advocacy

The most common decision process tends to be an advocacy decision process – you are asking somebody to sell you an answer. Once you are in advocacy mode, you are no longer in a decision-quality mode and you cannot get the best choice out of an advocacy decision process. Advocacy suppresses alternatives. Advocacy forces confirming evidence bias and means selective attention to what supports your position. Once in advocacy mode, you are really in a sales mode and it becomes a people competition.

When you want quality in a decision, you want the alternatives to compete, not the people. From the decision board’s perspective, when you are making a decision, you want to have multiple alternatives in front of you and you want to figure out which of these alternatives beats the others in terms of understanding the full consequences in risk, uncertainty and return. For each of the alternatives one will show up better. If you can make this happen, then it is not the advocate selling it, it is you trying to help look at which of these things gives us the most value for our investment in some way.

The role outcomes play in the measuring of decision quality

Always think of decisions and outcomes as separate because when you make decisions in an uncertain world, you cannot fully control the outcomes. When looking back from an outcome to a decision, the only thing you can really tell is if you had a good outcome or a bad outcome. Hindsight bias is strong, and once triggered, it is hard to put yourself back into understanding what decisions should have been made with what you knew, or could have known, at the time.

In understanding how we use outcomes in terms of evaluating decisions, you need to understand the importance of documenting the decision and the decision quality at the time of the decision. Ask yourself, if you were going to look back two years from now, what about this decision file answers the questions: “Did we make a decision that was good?” and “What can we learn about the things about which we had some questions?” This kind of documentation is different from what people usually do. What is usually documented is the approval and the working process. There is usually no documentation answering the question: “If we are going to look back in the future, what would we need to know to be able to learn about making better decisions?”

The reason you want to look back is because that is the way you learn and improve the whole decision process. It is not for blaming; in the end, what you are trying to show in documentation is: “We made the best decision we could then. Here is what we thought about the uncertainties. Here is what we thought were the driving factors.” Its about having a learning culture.

When decision makers and individuals understand the importance of reaching quality in each of the six requirements, they feel meeting those requirements is a decision-making right and should be demanded as part of the decision process. To be in a position where they can make a good decision, they know they deserve a good frame and significantly different alternatives or they cannot be in a position to reach a powerful, correct conclusion and make a decision. From a decision-maker’s perspective, these are indeed needs and rights to be thought about. From a decision support perspective, these needs and rights are required to be able to position the decision maker to make a good choice.

Building decision-quality enables measurable value creation and its framework can be learned, implemented and measured. Decision-quality helps you navigate the complexity of uncertainty of significant and strategic choices, avoid mega biases and big decision traps.