Research on expertise has identified the following differences between expert performers and beginners

- Experts have larger and more integrative knowledge units, and their representations of information are more functional and abstract than those of novices, whose knowledge base is more fragmentary. For example, a beginning piano player reads sheet music note by note, whereas a concert pianist is able to see the whole row or even several rows of music notation at the same time.

- When solving problems, experts may spend more time on the initial problem evaluation and planning than novices. This enables them to form a holistic and in-depth understanding of the task and usually to reach a solution more swiftly than beginners.

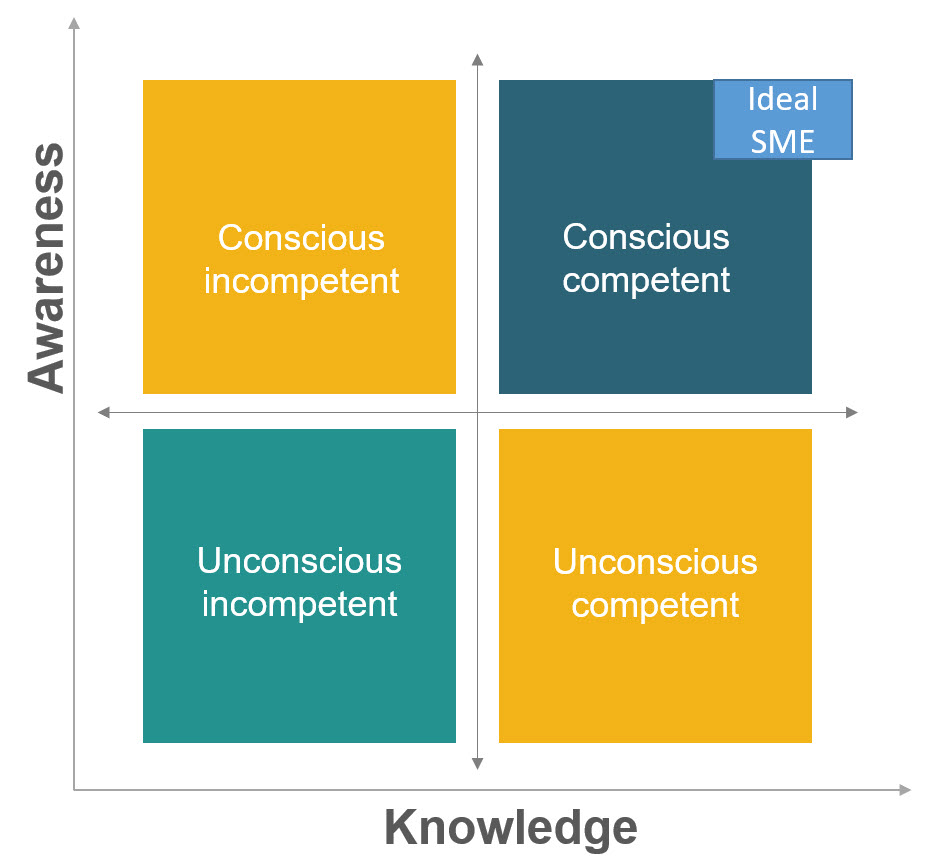

- Basic functions related to tasks or the job are automated in experts, whereas beginners need to pay attention to these functions. For instance, in a driving Basic functions related to tasks or the job are automated in experts, whereas beginners need to pay attention to these functions. For instance, in a driving school, a young driver focuses his or her attention on controlling devices and pedals, while an experienced driver performs basic strokes automatically. For this reason, an expert driver can observe and anticipate traffic situations better than a beginning driver.

- Experts outperform novices in their metacognitive and reflective thinking. In other words, they make sharp observations of their own ways of thinking, acting, and working, especially in non-routine situations when auto mated activities are challenged. Beginners’ knowledge is mainly explicit and they are dependent on learned rules. In addition to explicit knowledge, experts have tacit or implicit knowledge that accumulates with experience. This kind of knowledge makes it possible to make fast decisions on the basis of what is often called intuition.

- In situations where something has gone wrong or when experts face totally new problems but are not required to make fast decisions, they critically reflect on their actions. Unlike beginners, experienced professionals focus their thinking not only on details but rather on the totality consisting of the details.

- Experts’ thinking is more holistic than the thinking of novices. It seems that the quality of thinking is associated with the quality and amount of knowledge. With a fragmentary knowledge base, a novice in any field may remain on lower levels of thinking: things are seen as black and white, without any nuances. In contrast, more experienced colleagues with a more organized and holistic knowledge base can access more material for their thinking, and, thus, may begin to explore different perspectives on matters and develop more relativistic views concerning certain problems. At the highest levels of thinking, an individual is able to reconcile different perspectives, either by forming a synthesis or by integrating different approaches or views.

| Level | Performance |

| Beginner | Follows simple directions |

| Novice | Performs using memory of facts and simple rules |

| Competent | Makes simple judgmentsfor typical tasksMay need help withcomplex or unusual tasksMay lack speed andflexibility |

| Proficient | Performance guided by deeper experience Able to figure out the most critical aspects of a situation Sees nuances missed by less-skilled performers Flexible performance |

| Expert | Performance guided by extensive practice and easily retrievable knowledge and skillsNotices nuances, connections, and patterns Intuitive understanding based on extensive practice Able to solve difficult problems, learn quickly, and find needed resources |

Sources

- Clark, R. 2003. Building Expertise: Cognitive Methods for Training and Performance Improvement, 2nd ed. Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement.

- Ericsson, K.A. 2016. Peak: Secrets From the New Science of Expertise. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Kallio, E, ed. Development of Adult Thinking : Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Cognitive Development and Adult Learning. Taylor & Francis Group, 2020.

.