The pharmaceutical industry is navigating a transformative period in contamination control, driven by the convergence of updated international standards. The U.S. Pharmacopeia’s draft chapter〈1110〉 Microbial Contamination Control Strategy Considerations (March 2025) joins EU GMP Annex 1 (2022) in emphasizing risk-based strategies but differ in technical requirements and classification systems.

USP〈1110〉: A Lifecycle-Oriented Microbial Control Framework

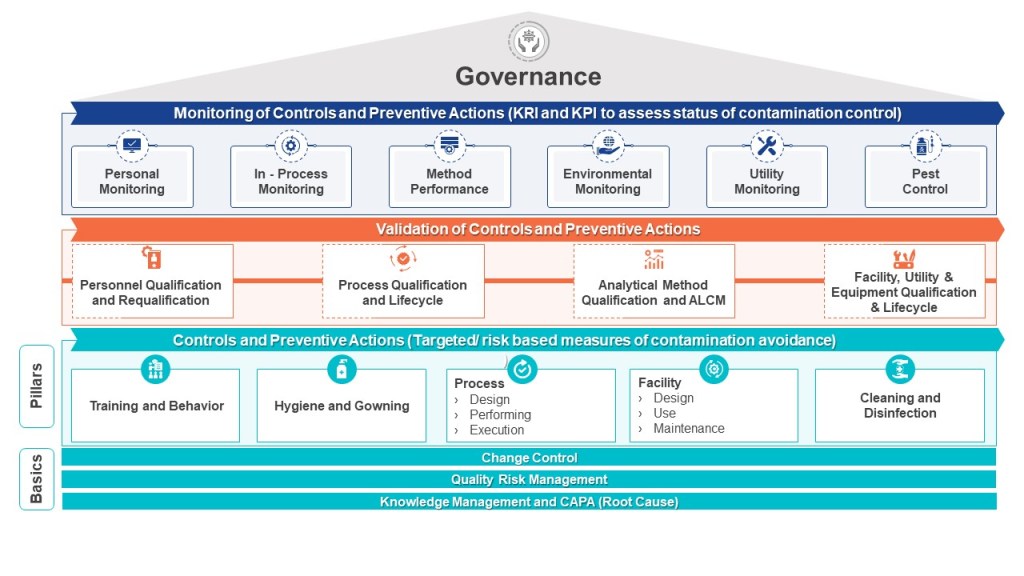

The draft USP chapter introduces a comprehensive contamination control strategy (CCS) that spans the entire product lifecycle, from facility design to post-market surveillance. It emphasizes microbial, endotoxin, and pyrogen risks, requiring manufacturers to integrate quality risk management (QRM) into every operational phase. Facilities must adopt ISO 14644-1 cleanroom classifications, with ISO Class 5 (≤3,520 particles ≥0.5 µm/m³) mandated for aseptic processing areas. Environmental monitoring programs must include both viable (microbial) and nonviable particles, with data trends analyzed quarterly to refine alert/action levels. Unlike Annex 1, USP allows flexibility in risk assessment methodologies but mandates documented justifications for control measures, such as the use of closed systems or isolators to minimize human intervention.

EU GMP Annex 1: Granular Cleanroom and Sterilization Requirements

Annex 1 builds on ISO 14644-1 cleanroom standards but introduces pharmaceutical-specific adaptations through its Grade A–D system. Grade A zones (critical processing areas) require ISO Class 5 conditions during both “at-rest” and “in-operation” states, with continuous particle monitoring and microbial limits of <1 CFU/m³. Annex 1 also mandates smoke studies to validate unidirectional airflow patterns in Grade A areas, a requirement absent in ISO 14644-1. Sterilization processes, such as autoclaving and vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) treatments, require pre- and post-use integrity testing, aligning with its focus on sterility assurance.

Reconciling Annex 1 and ISO 14644-1 Cleanroom Classifications

While both frameworks reference ISO 14644-1, Annex 1 overlays additional pharmaceutical requirements:

| Aspect | EU GMP Annex 1 | ISO 14644-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Classification System | Grades A–D mapped to ISO classes | ISO Class 1–9 based on particle counts |

| Particle Size | ≥0.5 µm and ≥5.0 µm monitoring for Grades A–B | ≥0.1 µm to ≥5.0 µm, depending on class |

| Microbial Limits | Explicit CFU/m³ limits for each grade | No microbial criteria; focuses on particles |

| Operational States | Qualification required for “at-rest” and “in-operation” states | Single-state classification permitted |

| Airflow Validation | Smoke studies mandatory for Grade A | Airflow pattern testing optional |

For example, a Grade B cleanroom (ISO Class 7 at rest) must maintain ISO Class 7 particle counts during production but adheres to stricter microbial limits (≤10 CFU/m³) than ISO 14644-1 alone. Manufacturers must design monitoring programs that satisfy both standards, such as deploying continuous particle counters for Annex 1 compliance while maintaining ISO certification reports.

| Classification | Description |

| Grade A | Critical area for high-risk and aseptic operations that corresponds to ISO 5 at rest/static and ISO 4.8 (in-operation/dynamic). Grade A areas apply to aseptic operations where the sterile product, product primary packaging components and product-contact surfaces are exposed to the environment. Normally Grade A conditions are provided by localized air flow protection, such as unidirectional airflow workstations within a Restricted Access Barrier System (RABS) or isolator. Direct intervention (e.g., without the protection of barrier and glove port protection) into the Grade A area by operators must be minimized by premises, equipment, process, or procedural design. |

| Grade B | For aseptic preparation and filling, this is the background area for Grade A (where it is not an isolator) and corresponds to ISO 5 at rest/static and ISO 7 in-operation/dynamic. Air pressure differences must be continuously monitored. Classified spaces of lower grade can be considered with the appropriate risk assessment and technical justification. |

| Grade C | Used for carrying out less critical steps in the manufacture of aseptically filled sterile products or as a background for isolators. They can also be used for the preparation/filling of terminally sterilized products. Grade C correspond to ISO 7 at rest/static and ISO 8 in-operation/dynamic. |

| Grade D | Used to carry out non-sterile operations and corresponds to ISO 8 at rest/static and in-operation/dynamic. |

Risk Management: Divergent Philosophies, Shared Objectives

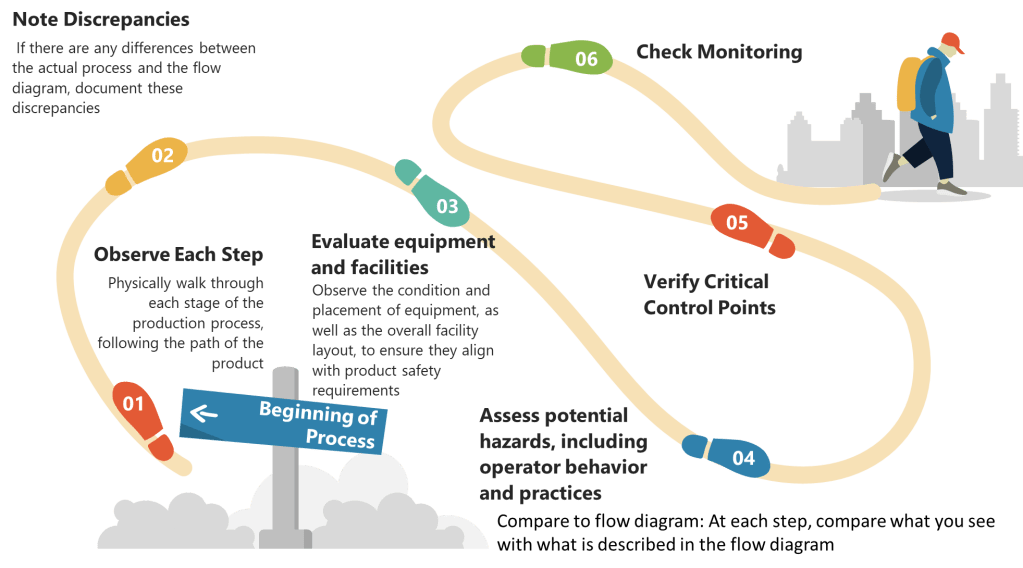

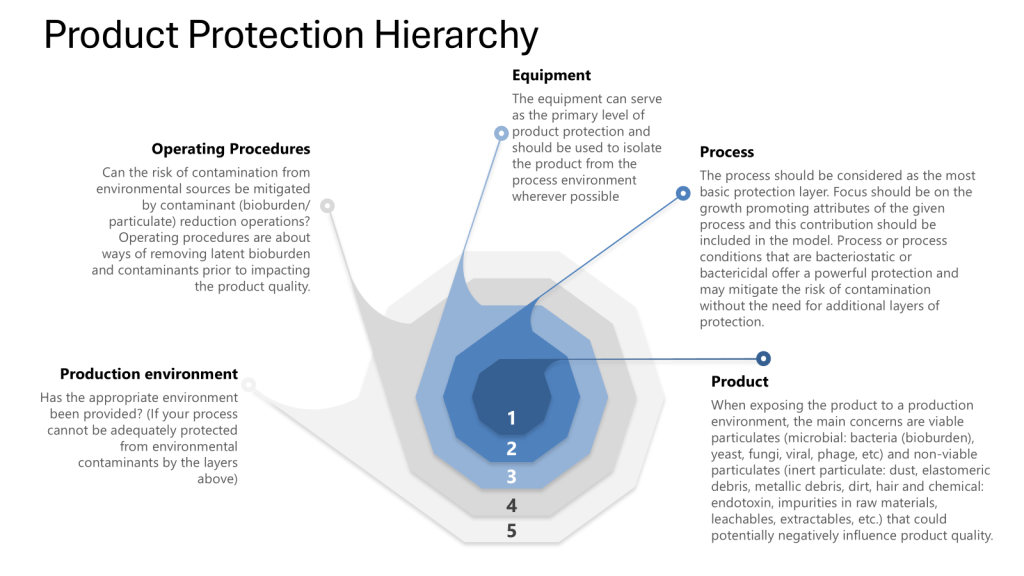

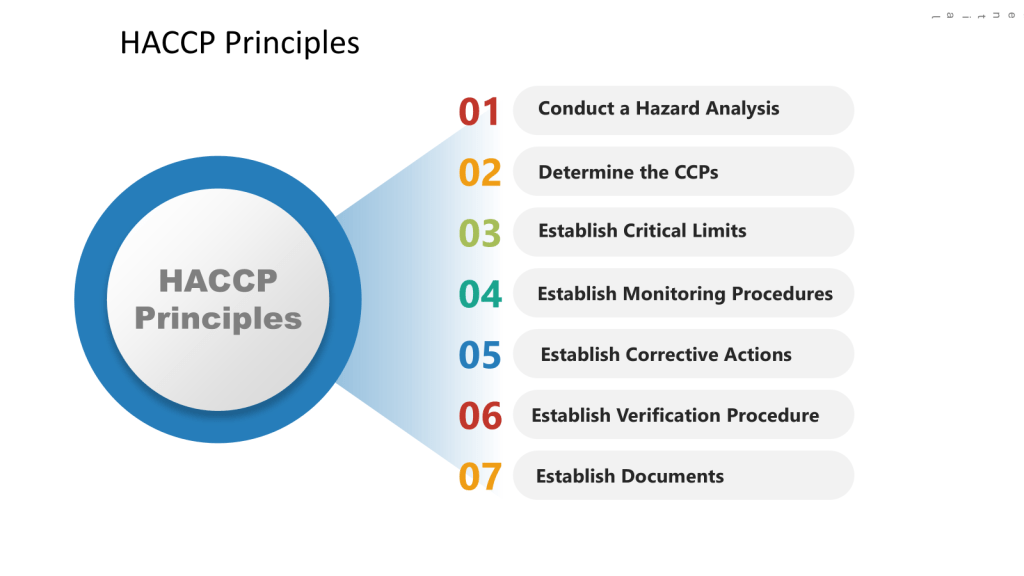

Both frameworks require Quality Risk Management. USP〈1110〉advocates for a flexible, science-driven approach, allowing tools like HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points) or FMEA (Failure Modes Effects Analysis) to identify critical control points. For instance, a biologics manufacturer might use HACCP to prioritize endotoxin controls during cell culture harvesting. USP also emphasizes lifecycle risk reviews, requiring CCS updates after facility modifications or adverse trend detections.

Annex 1 mandates formal QRM processes with documented risk assessments for all sterilization and aseptic processes. Its Annex 1.25 clause requires FMEA for media fill simulations, ensuring worst-case scenarios (e.g., maximum personnel presence) are tested. Risk assessments must also justify cleanroom recovery times after interventions, linking airflow validation data to contamination probability.

A harmonized approach involves:

- Baseline Risk Identification: Use HACCP to map contamination risks across product stages, aligning with USP’s lifecycle focus.

- Control Measure Integration: Apply Annex 1’s sterilization and airflow requirements to critical risks identified in USP’s CCS.

- Continuous Monitoring: Combine USP’s trend analysis with continuous monitoring for real-time risk mitigation.

Strategic Implementation Considerations

Reconciling these standards requires a multi-layered strategy. Facilities must first achieve ISO 14644-1 certification for particle counts, then overlay Annex 1’s microbial and operational requirements. For example, an ISO Class 7 cleanroom used for vial filling would need Grade B microbial monitoring (≤10 CFU/m³) and quarterly smoke studies to validate airflow. Risk management documentation should cross-reference USP’s CCS objectives with Annex 1’s sterilization validations, creating a unified audit trail. Training programs must blend USP’s aseptic technique modules with Annex 1’s cleanroom behavior protocols, ensuring personnel understand both particle control and microbial hygiene.

Toward Global Harmonization

The draft USP〈1110〉and Annex 1 represent complementary pillars of modern contamination control. By anchoring cleanroom designs to ISO 14644-1 and layering region-specific requirements, manufacturers can streamline compliance across jurisdictions. Proactive risk management—combining USP’s flexibility with Annex 1’s rigor—will be pivotal in navigating this evolving landscape. As regulatory expectations converge, firms that invest in integrated CCS platforms will gain agility in an increasingly complex global market.