The November 2025 FDA Warning Letter to Catalent Indiana, LLC reads like an autopsy report—a detailed dissection of how contamination hazards aren’t discovered but rather engineered into aseptic operations through a constellation of decisions that individually appear defensible yet collectively create what I’ve previously termed the “zemblanity field” in pharmaceutical quality. Section 2, addressing failures under 21 CFR 211.113(b), exposes contamination hazards that didn’t emerge from random misfortune but from deliberate choices about decontamination strategies, sampling methodologies, intervention protocols, and investigation rigor.

What makes this warning letter particularly instructive isn’t the presence of contamination events—every aseptic facility battles microbial ingress—but rather the systematic architectural failures that allowed contamination hazards to persist unrecognized, uninvestigated, and unmitigated despite multiple warning signals spanning more than 20 deviations and customer complaints. The FDA’s critique centers on three interconnected contamination hazard categories: VHP decontamination failures involving occluded surfaces, inadequate environmental monitoring methods that substituted convenience for detection capability, and intervention risk assessments that ignored documented contamination routes.

For those of us responsible for contamination control in aseptic manufacturing, this warning letter demands we ask uncomfortable questions: How many of our VHP cycles are validated against surfaces that remain functionally occluded? How often have we chosen contact plates over swabs because they’re faster, not because they’re more effective? When was the last time we terminated a media fill and treated it with the investigative rigor of a batch contamination event?

The Occluded Surface Problem: When Decontamination Becomes Theatre

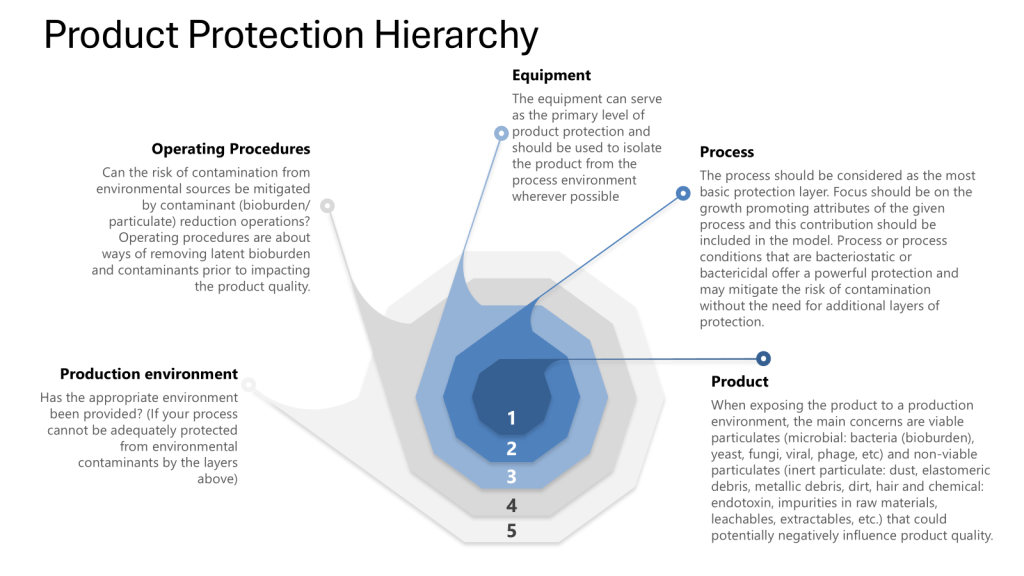

The FDA’s identification of occluded surfaces as contamination sources during VHP decontamination represents a failure mode I’ve observed with troubling frequency across aseptic facilities. The fundamental physics are unambiguous: vaporized hydrogen peroxide achieves sporicidal efficacy through direct surface contact at validated concentration-time profiles. Any surface the vapor doesn’t contact—or contacts at insufficient concentration—remains a potential contamination reservoir regardless of cycle completion indicators showing “successful” decontamination.

The Catalent situation involved two distinct occluded surface scenarios, each revealing different architectural failures in contamination hazard assessment. First, equipment surfaces occluded during VHP decontamination that subsequently became contamination sources during atypical interventions involving equipment changes. The FDA noted that “the most probable root cause” of an environmental monitoring failure was equipment surfaces occluded during VHP decontamination, with contamination occurring during execution of an atypical intervention involving changes to components integral to stopper seating.

This finding exposes a conceptual error I frequently encounter: treating VHP decontamination as a universal solution that overcomes design deficiencies rather than as a validated process with specific performance boundaries. The Catalent facility’s own risk assessments advised against interventions that could disturb potentially occluded surfaces, yet these interventions continued—creating the precise contamination pathway their risk assessments identified as unacceptable.

The second occluded surface scenario involved wrapped components within the filling line where insufficient VHP exposure allowed potential contamination. The FDA cited “occluded surfaces on wrapped [components] within the [equipment] as the potential cause of contamination”. This represents a validation failure: if wrapping materials prevent adequate VHP penetration, either the wrapping must be eliminated, the decontamination method must change, or these surfaces must be treated through alternative validated processes.

The literature on VHP decontamination is explicit about occluded surface risks. As Sandle notes, surfaces must be “designed and installed so that operations, maintenance, and repairs can be performed outside the cleanroom” and where unavoidable, “all surfaces needing decontaminated” must be explicitly identified. The PIC/S guidance is similarly unambiguous: “Continuously occluded surfaces do not qualify for such trials as they cannot be exposed to the process and should have been eliminated”. Yet facilities continue to validate VHP cycles that demonstrate biological indicator kill on readily accessible flat coupons while ignoring the complex geometries, wrapped items, and recessed surfaces actually present in their filling environments.

What does a robust approach to occluded surface assessment look like? Based on the regulatory expectations and technical literature, facilities should:

Conduct comprehensive occluded surface mapping during design qualification. Every component introduced into VHP-decontaminated spaces must undergo geometric analysis to identify surfaces that may not receive adequate vapor exposure. This includes crevices, threaded connections, wrapped items, hollow spaces, and any surface shadowed by another object. The mapping should document not just that surfaces exist but their accessibility to vapor flow based on the specific VHP distribution characteristics of the equipment.

Validate VHP distribution using chemical and biological indicators placed on identified occluded surfaces. Flat coupon placement on readily accessible horizontal surfaces tells you nothing about vapor penetration into wrapped components or recessed geometries. Biological indicators should be positioned specifically where vapor exposure is questionable—inside wrapped items, within threaded connections, under equipment flanges, in dead-legs of transfer lines. If biological indicators in these locations don’t achieve the validated log reduction, the surfaces are occluded and require design modification or alternative decontamination methods.

Establish clear intervention protocols that distinguish between “sterile-to-sterile” and “potentially contaminated” surface contact. The Catalent finding reveals that atypical interventions involving equipment changes exposed the Grade A environment to surfaces not reliably exposed to VHP. Intervention risk assessments must explicitly categorize whether the intervention involves only VHP-validated surfaces or introduces components from potentially occluded areas. The latter category demands heightened controls: localized Grade A air protection, pre-intervention surface swabbing and disinfection, real-time environmental monitoring during the intervention, and post-intervention investigation if environmental monitoring shows any deviation.

Implement post-decontamination surface monitoring that targets historically occluded locations. If your facility has identified occluded surfaces that cannot be designed out, these become critical sampling locations for post-VHP environmental monitoring. Trending of these specific locations provides early detection of decontamination effectiveness degradation before contamination reaches product-contact surfaces.

The FDA’s remediation demand is appropriately comprehensive: “a review of VHP exposure to decontamination methods as well as permitted interventions, including a retrospective historical review of routine interventions and atypical interventions to determine their risks, a comprehensive identification of locations that are not reliably exposed to VHP decontamination (i.e., occluded surfaces), your plan to reduce occluded surfaces where feasible, review of currently permitted interventions and elimination of high-risk interventions entailing equipment manipulations during production campaigns that expose the ISO 5 environment to surfaces not exposed to a validated decontamination process, and redesign of any intervention that poses an unacceptable contamination risk”.

This remediation framework represents best practice for any aseptic facility using VHP decontamination. The occluded surface problem isn’t limited to Catalent—it’s an industry-wide vulnerability wherever VHP validation focuses on demonstrating sporicidal activity under ideal conditions rather than confirming adequate vapor contact across all surfaces within the validated space.

Contact Plates Versus Swabs: The Detection Capability Trade-Off

The FDA’s critique of Catalent’s environmental monitoring methodology exposes a decision I’ve challenged repeatedly throughout my career: the use of contact plates for sampling irregular, product-contact surfaces in Grade A environments. The technical limitations are well-established, yet contact plates persist because they’re faster and operationally simpler—prioritizing workflow convenience over contamination detection capability.

The specific Catalent deficiency involved sampling filling line components using “contact plate, sampling [surfaces] with one sweeping sampling motion.” The FDA identified two fundamental inadequacies: “With this method, you are unable to attribute contamination events to specific [locations]” and “your firm’s use of contact plates is not as effective as using swab methods”. These limitations aren’t novel discoveries—they’re inherent to contact plate methodology and have been documented in the microbiological literature for decades.

Contact plates—rigid agar surfaces pressed against the area to be sampled—were designed for flat, smooth surfaces where complete agar-to-surface contact can be achieved with uniform pressure. They perform adequately on stainless steel benchtops, isolator walls, and other horizontal surfaces. But filling line components—particularly those identified in the warning letter—present complex geometries: curved surfaces, corners, recesses, and irregular topographies where rigid agar cannot conform to achieve complete surface contact.

The microbial recovery implications are significant. When a contact plate fails to achieve complete surface contact, microorganisms in uncontacted areas remain unsampled. The result is a false-negative environmental monitoring reading that suggests contamination control while actual contamination persists undetected. Worse, the “sweeping sampling motion” described in the warning letter—moving a single contact plate across multiple locations—creates the additional problem the FDA identified: inability to attribute any recovered contamination to a specific surface. Was the contamination on the first component contacted? The third? Somewhere in between? This sampling approach provides data too imprecise for meaningful contamination source investigation.

The alternative—swab sampling—addresses both deficiencies. Swabs conform to irregular surfaces, accessing corners, recesses, and curved topographies that contact plates cannot reach. Swabs can be applied to specific, discrete locations, enabling precise attribution of any contamination recovered to a particular surface. The trade-off is operational: swab sampling requires more time, involves additional manipulative steps within Grade A environments, and demands different operator technique validation.

Yet the Catalent warning letter makes clear that this operational inconvenience doesn’t justify compromised detection capability for critical product-contact surfaces. The FDA’s expectation—acknowledged in Catalent’s response—is swab sampling “to replace use of contact plates to sample irregular surfaces”. This represents a fundamental shift from convenience-optimized to detection-optimized environmental monitoring.

What should a risk-based surface sampling strategy look like? The differentiation should be based on surface geometry and criticality:

Contact plates remain appropriate for flat, smooth, readily accessible surfaces where complete agar contact can be verified and where contamination risk is lower (Grade B floors, isolator walls, equipment external surfaces). The speed and simplicity advantages of contact plates justify their continued use in these applications.

Swab sampling should be mandatory for product-contact surfaces, irregular geometries, recessed areas, and any location where contact plate conformity is questionable. This includes filling needles, stopper bowls, vial transport mechanisms, crimping heads, and the specific equipment components cited in the Catalent letter. The additional time required for swab sampling is trivial compared to the contamination risk from inadequate monitoring.

Surface sampling protocols must specify the exact location sampled, not general equipment categories. Rather than “sample stopper bowl,” protocols should identify “internal rim of stopper bowl,” “external base of stopper bowl,” “stopper agitation mechanism interior surfaces.” This specificity enables contamination source attribution during investigations and ensures sampling actually reaches the highest-risk surfaces.

Swab technique must be validated to ensure consistent recovery from target surfaces. Simply switching from contact plates to swabs doesn’t guarantee improved detection unless swab technique—pressure applied, surface area contacted, swab saturation, transfer to growth media—is standardized and demonstrated to achieve adequate microbial recovery from the specific materials and geometries being sampled.

The EU GMP Annex 1 and FDA guidance documents emphasize detection capability over convenience in environmental monitoring. The expectation isn’t perfect contamination prevention—that’s impossible in aseptic processing—but rather monitoring systems sensitive enough to detect contamination events when they occur, enabling investigation and corrective action before product impact. Contact plates on irregular surfaces fail this standard by design, not because of operator error or inadequate validation but because the fundamental methodology cannot access the surfaces requiring monitoring.

The Intervention Paradox: When Risk Assessments Identify Hazards But Operations Ignore Them

Perhaps the most troubling element of the Catalent contamination hazards section isn’t the presence of occluded surfaces or inadequate sampling methods but rather the intervention management failure that reveals a disconnect between risk assessment and operational decision-making. Catalent’s risk assessments explicitly “advised against interventions that can disturb potentially occluded surfaces,” yet these high-risk interventions continued during production campaigns.

This represents what I’ve termed “investigation theatre” in previous posts—creating the superficial appearance of risk-based decision-making while actual operations proceed according to production convenience rather than contamination risk mitigation. The risk assessment identified the hazard. The environmental monitoring data confirmed the hazard when contamination occurred during the intervention. Yet the intervention continued as an accepted operational practice.

The specific intervention involved equipment changes to components “integral to stopper seating in the [filling line]”. These components operate at the critical interface between the sterile stopper and the vial—precisely the location where any contamination poses direct product impact risk. The intervention occurred during production campaigns rather than between campaigns when comprehensive decontamination and validation could occur. The intervention involved surfaces potentially occluded during VHP decontamination, meaning their microbiological state was unknown when introduced into the Grade A filling environment.

Every element of this scenario screams “unacceptable contamination risk,” yet it persisted as accepted practice until FDA inspection. How does this happen? Based on my experience across multiple aseptic facilities, the failure mode follows a predictable pattern:

Production scheduling drives intervention timing rather than contamination risk assessment. Stopping a campaign for equipment maintenance creates schedule disruption, yield loss, and capacity constraints. The pressure to maintain campaign continuity overwhelms contamination risk considerations that appear theoretical compared to the immediate, quantifiable production impact.

Risk assessments become compliance artifacts disconnected from operational decision-making. The quality unit conducts a risk assessment, documents that certain interventions pose unacceptable contamination risk, and files the assessment. But when production encounters the situation requiring that intervention, the actual decision-making process references production need, equipment availability, and batch schedules—not the risk assessment that identified the intervention as high-risk.

Interventions become “normalized deviance”—accepted operational practices despite documented risks. After performing a high-risk intervention successfully (meaning without detected contamination) multiple times, it transitions from “high-risk intervention requiring exceptional controls” to “routine intervention” in operational thinking. The fact that adequate controls prevented contamination detection gets inverted into evidence that the intervention isn’t actually high-risk.

Environmental monitoring provides false assurance when contamination goes undetected. If a high-risk intervention occurs and subsequent environmental monitoring shows no contamination, operations interprets this as validation that the intervention is acceptable. But as discussed in the contact plate section, inadequate sampling methodology may fail to detect contamination that actually occurred. The absence of detected contamination becomes “proof” that contamination didn’t occur, reinforcing the normalization of high-risk interventions.

The EU GMP Annex 1 requirements for intervention management represent regulatory recognition of these failure modes. Annex 1 Section 8.16 requires “the list of interventions evaluated via risk analysis” and Section 9.36 requires that aseptic process simulations include “interventions and associated risks”. The framework is explicit: identify interventions, assess their contamination risk, validate that operators can perform them aseptically through media fills, and eliminate interventions that cannot be performed without unacceptable contamination risk.

What does robust intervention risk management look like in practice?

Categorize interventions by contamination risk based on specific, documented criteria. The categorization should consider: surfaces contacted (sterile-to-sterile vs. potentially contaminated), duration of exposure, proximity to open product, operator actions required, first air protection feasibility, and frequency. This creates a risk hierarchy that enables differentiated control strategies rather than treating all interventions equivalently.

Establish clear decision authorities for different intervention risk levels. Routine interventions (low contamination risk, validated through media fills, performed regularly) can proceed under operator judgment following standard procedures. High-risk interventions (those involving occluded surfaces, extended exposure, or proximity to open product) should require quality unit pre-approval including documented risk assessment and enhanced controls specification. Interventions identified as posing unacceptable risk should be prohibited until equipment redesign or process modification eliminates the contamination hazard.

Validate intervention execution through media fills that specifically simulate the intervention’s contamination challenges. Generic media fills demonstrating overall aseptic processing capability don’t validate specific high-risk interventions. If your risk assessment identifies a particular intervention as posing contamination risk, your media fill program must include that intervention, performed by the operators who will execute it, under the conditions (campaign timing, equipment state, environmental conditions) where it will actually occur.

Implement intervention-specific environmental monitoring that targets the contamination pathways identified in risk assessments. If the risk assessment identifies that an intervention may expose product to surfaces not reliably decontaminated, environmental monitoring immediately following that intervention should specifically sample those surfaces and adjacent areas. Trending this intervention-specific monitoring data separately from routine environmental monitoring enables detection of intervention-associated contamination patterns.

Conduct post-intervention investigations when environmental monitoring shows any deviation. The Catalent warning letter describes an environmental monitoring failure whose “most probable root cause” was an atypical intervention involving equipment changes. This temporal association between intervention and contamination should trigger automatic investigation even if environmental monitoring results remain within action levels. The investigation should assess whether intervention protocols require modification or whether the intervention should be eliminated.

The FDA’s remediation demand addresses this gap directly: “review of currently permitted interventions and elimination of high-risk interventions entailing equipment manipulations during production campaigns that expose the ISO 5 environment to surfaces not exposed to a validated decontamination process”. This requirement forces facilities to confront the intervention paradox: if your risk assessment identifies an intervention as high-risk, you cannot simultaneously permit it as routine operational practice. Either modify the intervention to reduce risk, validate enhanced controls that mitigate the risk, or eliminate the intervention entirely.

Media Fill Terminations: When Failures Become Invisible

The Catalent warning letter’s discussion of media fill terminations exposes an investigation failure mode that reveals deeper quality system inadequacies. Since November 2023, Catalent terminated more than five media fill batches representing the filling line. Following two terminations for stoppering issues and extrinsic particle contamination, the facility “failed to open a deviation or an investigation at the time of each failure, as required by your SOPs”.

Read that again. Media fills—the fundamental aseptic processing validation tool, the simulation specifically designed to challenge contamination control—were terminated due to failures, and no deviation was opened, no investigation initiated. The failures simply disappeared from the quality system, becoming invisible until FDA inspection revealed their existence.

The rationalization is predictable: “there was no impact to the SISPQ (Safety, Identity, Strength, Purity, Quality) of the terminated media batches or to any customer batches” because “these media fills were re-executed successfully with passing results”. This reasoning exposes a fundamental misunderstanding of media fill purpose that I’ve encountered with troubling frequency across the industry.

A media fill is not a “test” that you pass or fail with product consequences. It is a simulation—a deliberate challenge to your aseptic processing capability using growth medium instead of product specifically to identify contamination risks without product impact. When a media fill is terminated due to a processing failure, that termination is itself the critical finding. The termination reveals that your process is vulnerable to exactly the failure mode that caused termination: stoppering problems that could occur during commercial filling, extrinsic particles that could contaminate product.

The FDA’s response is appropriately uncompromising: “You do not provide the investigations with a root cause that justifies aborting and re-executing the media fills, nor do you provide the corrective actions taken for each terminated media fill to ensure effective CAPAs were promptly initiated”. The regulatory expectation is clear: media fill terminations require investigation identical in rigor to commercial batch failures. Why did the stoppering issue occur? What equipment, material, or operator factors contributed? How do we prevent recurrence? What commercial batches may have experienced similar failures that went undetected?

The re-execution logic is particularly insidious. By immediately re-running the media fill and achieving passing results, Catalent created the appearance of successful validation while ignoring the process vulnerability revealed by the termination. The successful re-execution proved only that under ideal conditions—now with heightened operator awareness following the initial failure—the process could be executed successfully. It provided no assurance that commercial operations, without that heightened awareness and under the same conditions that caused the initial termination, wouldn’t experience identical failures.

What should media fill termination management look like?

Treat every media fill termination as a critical deviation requiring immediate investigation initiation. The investigation should identify the root cause of the termination, assess whether the failure mode could occur during commercial manufacturing, evaluate whether previous commercial batches may have experienced similar failures, and establish corrective actions that prevent recurrence. This investigation must occur before re-execution, not instead of investigation.

Require quality unit approval before media fill re-execution. The approval should be based on documented investigation findings demonstrating that the termination cause is understood, corrective actions are implemented, and re-execution will validate process capability under conditions that include the corrective actions. Re-execution without investigation approval perpetuates the “keep running until we get a pass” mentality that defeats media fill purpose.

Implement media fill termination trending as a critical quality indicator. A facility terminating “more than five media fill batches” in a period should recognize this as a signal of fundamental process capability problems, not as a series of unrelated events requiring re-execution. Trending should identify common factors: specific operators, equipment states, intervention types, campaign timing.

Ensure deviation tracking systems cannot exclude media fill terminations. The Catalent situation arose partly because “you failed to initiate a deviation record to capture the lack of an investigation for each of the terminated media fills, resulting in an undercounting of the deviations”. Quality metrics that exclude media fill terminations from deviation totals create perverse incentives to avoid formal deviation documentation, rendering media fill findings invisible to quality system oversight.

The broader issue extends beyond media fill terminations to how aseptic processing validation integrates with quality systems. Media fills should function as early warning indicators—detecting aseptic processing vulnerabilities before product impact occurs. But this detection value requires that findings from media fills drive investigations, corrective actions, and process improvements with the same rigor as commercial batch deviations. When media fill failures can be erased through re-execution without investigation, the entire validation framework becomes performative rather than protective.

The Stopper Supplier Qualification Failure: Accepting Contamination at the Source

The stopper contamination issues discussed throughout the warning letter—mammalian hair found in or around stopper regions of vials from nearly 20 batches across multiple products—reveal a supplier qualification and incoming inspection failure that compounds the contamination hazards already discussed. The FDA’s critique focuses on Catalent’s “inappropriate reliance on pre-shipment samples (tailgate samples)” and failure to implement “enhanced or comparative sampling of stoppers from your other suppliers”.

The pre-shipment or “tailgate” sample approach represents a fundamental violation of GMP sampling principles. Under this approach, the stopper supplier—not Catalent—collected samples from lots prior to shipment and sent these samples directly to Catalent for quality testing. Catalent then made accept/reject decisions for incoming stopper lots based on testing of supplier-selected samples that never passed through Catalent’s receiving or storage processes.

Why does this matter? Because representative sampling requires that samples be selected from the material population actually received by the facility, stored under facility conditions, and handled through facility processes. Supplier-selected pre-shipment samples bypass every opportunity to detect contamination introduced during shipping, storage transitions, or handling. They enable a supplier to selectively sample from cleaner portions of production lots while shipping potentially contaminated material in the same lot to the customer.

The FDA guidance on this issue is explicit and has been for decades: samples for quality attribute testing “are to be taken at your facility from containers after receipt to ensure they are representative of the components in question”. This isn’t a new expectation emerging from enhanced regulatory scrutiny—it’s a baseline GMP requirement that Catalent systematically violated through reliance on tailgate samples.

But the tailgate sample issue represents only one element of broader supplier qualification failures. The warning letter notes that “while stoppers from [one supplier] were the primary source of extrinsic particles, they were not the only source of foreign matter.” Yet Catalent implemented “limited, enhanced sampling strategy for one of your suppliers” while failing to “increase sampling oversight” for other suppliers. This selective enhancement—focusing remediation only on the most problematic supplier while ignoring systemic contamination risks across the stopper supply base—predictably failed to resolve ongoing contamination issues.

What should stopper supplier qualification and incoming inspection look like for aseptic filling operations?

Eliminate pre-shipment or tailgate sampling entirely. All quality testing must be conducted on samples taken from received lots, stored in facility conditions, and selected using documented random sampling procedures. If suppliers require pre-shipment testing for their internal quality release, that’s their process requirement—it doesn’t substitute for the purchaser’s independent incoming inspection using facility-sampled material.

Implement risk-based incoming inspection that intensifies sampling when contamination history indicates elevated risk. The warning letter notes that Catalent recognized stoppers as “a possible contributing factor for contamination with mammalian hairs” in July 2024 but didn’t implement enhanced sampling until May 2025—a ten-month delay. The inspection enhancement should be automatic and immediate when contamination events implicate incoming materials. The sampling intensity should remain elevated until trending data demonstrates sustained contamination reduction across multiple lots.

Apply visual inspection with reject criteria specific to the defect types that create product contamination risk. Generic visual inspection looking for general “defects” fails to detect the specific contamination types—embedded hair, extrinsic particles, material fragments—that create sterile product risks. Inspection protocols must specify mammalian hair, fiber contamination, and particulate matter as reject criteria with sensitivity adequate to detect single-particle contamination in sampled stoppers.

Require supplier process changes—not just enhanced sampling—when contamination trends indicate process capability problems. The warning letter acknowledges Catalent “worked with your suppliers to reduce the likelihood of mammalian hair contamination events” but notes that despite these efforts, “you continued to receive complaints from customers who observed mammalian hair contamination in drug products they received from you”. Enhanced sampling detects contamination; it doesn’t prevent it. Suppliers demonstrating persistent contamination require process audits, environmental control improvements, and validated contamination reduction demonstrated through process capability studies—not just promises to improve quality.

Implement finished product visual inspection with heightened sensitivity for products using stoppers from suppliers with contamination history. The FDA notes that Catalent indicated “future batches found during visual inspection of finished drug products would undergo a re-inspection followed by tightened acceptable quality limit to ensure defective units would be removed” but didn’t provide the re-inspection procedure. This two-stage inspection approach—initial inspection followed by re-inspection with enhanced criteria for lots from high-risk suppliers—provides additional contamination detection but must be validated to demonstrate adequate defect removal.

The broader lesson extends beyond stoppers to supplier qualification for any component used in sterile manufacturing. Components introduce contamination risks—microbial bioburden, particulate matter, chemical residues—that cannot be fully mitigated through end-product testing. Supplier qualification must function as a contamination prevention tool, ensuring that materials entering aseptic operations meet microbiological and particulate quality standards appropriate for their role in maintaining sterility. Reliance on tailgate samples, delayed sampling enhancement, and acceptance of persistent supplier contamination all represent failures to recognize suppliers as critical contamination control points requiring rigorous qualification and oversight.

The Systemic Pattern: From Contamination Hazards to Quality System Architecture

Stepping back from individual contamination hazards—occluded surfaces, inadequate sampling, high-risk interventions, media fill terminations, supplier qualification failures—a systemic pattern emerges that connects this warning letter to the broader zemblanity framework I’ve explored in previous posts. These aren’t independent, unrelated deficiencies that coincidentally occurred at the same facility. They represent interconnected architectural failures in how the quality system approaches contamination control.

The pattern reveals itself through three consistent characteristics:

Detection systems optimized for convenience rather than capability. Contact plates instead of swabs for irregular surfaces. Pre-shipment samples instead of facility-based incoming inspection. Generic visual inspection instead of defect-specific contamination screening. Each choice prioritizes operational ease and workflow efficiency over contamination detection sensitivity. The result is a quality system that generates reassuring data—passing environmental monitoring, acceptable incoming inspection results, successful visual inspection—while actual contamination persists undetected.

Risk assessments that identify hazards without preventing their occurrence. Catalent’s risk assessments advised against interventions disturbing potentially occluded surfaces, yet these interventions continued. The facility recognized stoppers as contamination sources in July 2024 but delayed enhanced sampling until May 2025. Media fill terminations revealed aseptic processing vulnerabilities but triggered re-execution rather than investigation. Risk identification became separated from risk mitigation—the assessment process functioned as compliance theatre rather than decision-making input.

Investigation systems that erase failures rather than learn from them. Media fill terminations occurred without deviation initiation. Mammalian hair contamination events were investigated individually without recognizing the trend across 20+ deviations. Root cause investigations concluded “no product impact” based on passing sterility tests rather than addressing the contamination source enabling future events. The investigation framework optimized for batch release justification rather than contamination prevention.

These patterns don’t emerge from incompetent quality professionals or inadequate resource allocation. They emerge from quality system design choices that prioritize production efficiency, workflow continuity, and batch release over contamination detection, investigation rigor, and source elimination. The system delivers what it was designed to deliver: maximum throughput with minimum disruption. It fails to deliver what patients require: contamination control capable of detecting and eliminating sterility risks before product impact.

Recommendations: Building Contamination Hazard Detection Into System Architecture

What does effective contamination hazard management look like at the quality system architecture level? Based on the Catalent failures and broader industry patterns, several principles should guide aseptic operations:

Design decontamination validation around worst-case geometries, not ideal conditions. VHP validation using flat coupons on horizontal surfaces tells you nothing about vapor penetration into the complex geometries, wrapped components, and recessed surfaces actually present in your filling line. Biological indicator placement should target occluded surfaces specifically—if you can’t achieve validated kill on these locations, they’re contamination hazards requiring design modification or alternative decontamination methods.

Select environmental monitoring methods based on detection capability for the surfaces and conditions actually requiring monitoring. Contact plates are adequate for flat, smooth surfaces. They’re inadequate for irregular product-contact surfaces, recessed areas, and complex geometries. Swab sampling takes more time but provides contamination detection capability that contact plates cannot match. The operational convenience sacrifice is trivial compared to the contamination risk from monitoring methods incapable of detecting contamination when it occurs.

Establish intervention risk classification with decision authorities proportional to contamination risk. Routine low-risk interventions validated through media fills can proceed under operator judgment. High-risk interventions—those involving occluded surfaces, extended exposure, or proximity to open product—require quality unit pre-approval with documented enhanced controls. Interventions identified as posing unacceptable risk should be prohibited pending equipment redesign.

Treat media fill terminations as critical deviations requiring investigation before re-execution. The termination reveals process vulnerability—the investigation must identify root cause, assess commercial batch risk, and establish corrective actions before validation continues. Re-execution without investigation perpetuates the failures that caused termination.

Implement supplier qualification with facility-based sampling, contamination-specific inspection criteria, and automatic sampling enhancement when contamination trends emerge. Tailgate samples cannot provide representative material assessment. Visual inspection must target the specific contamination types—mammalian hair, particulate matter, material fragments—that create product risks. Enhanced sampling should be automatic and sustained when contamination history indicates elevated risk.

Build investigation systems that learn from contamination events rather than erasing them through re-execution or “no product impact” conclusions. Contamination events represent failures in contamination control regardless of whether subsequent testing shows product remains within specification. The investigation purpose is preventing recurrence, not justifying release.

The FDA’s comprehensive remediation demands represent what quality system architecture should look like: independent assessment of investigation capability, CAPA effectiveness evaluation, contamination hazard risk assessment covering material flows and equipment placement, detailed remediation with specific improvements, and ongoing management oversight throughout the manufacturing lifecycle.

The Contamination Control Strategy as Living System

The Catalent warning letter’s contamination hazards section serves as a case study in how quality systems can simultaneously maintain surface-level compliance while allowing fundamental contamination control failures to persist. The facility conducted VHP decontamination cycles, performed environmental monitoring, executed media fills, and inspected incoming materials—checking every compliance box. Yet contamination hazards proliferated because these activities optimized for operational convenience and batch release justification rather than contamination detection and source elimination.

The EU GMP Annex 1 Contamination Control Strategy requirement represents regulatory recognition that contamination control cannot be achieved through isolated compliance activities. It requires integrated systems where facility design, decontamination processes, environmental monitoring, intervention protocols, material qualification, and investigation practices function cohesively to detect, investigate, and eliminate contamination sources. The Catalent failures reveal what happens when these elements remain disconnected: decontamination cycles that don’t reach occluded surfaces, monitoring that can’t detect contamination on irregular geometries, interventions that proceed despite identified risks, investigations that erase failures through re-execution

For those of us responsible for contamination control in aseptic manufacturing, the question isn’t whether our facilities face similar vulnerabilities—they do. The question is whether our quality systems are architected to detect these vulnerabilities before regulators discover them. Are your VHP validations addressing actual occluded surfaces or ideal flat coupons? Are you using contact plates because they detect contamination effectively or because they’re operationally convenient? Do your intervention protocols prevent the high-risk activities your risk assessments identify? When media fills terminate, do investigations occur before re-execution?

The Catalent warning letter provides a diagnostic framework for assessing contamination hazard management. Use it. Map your own decontamination validation against the occluded surface criteria. Evaluate your environmental monitoring method selection against detection capability requirements. Review intervention protocols for alignment with risk assessments. Examine media fill termination handling for investigation rigor. Assess supplier qualification for facility-based sampling and contamination-specific inspection.

The contamination hazards are already present in your aseptic operations. The question is whether your quality system architecture can detect them.