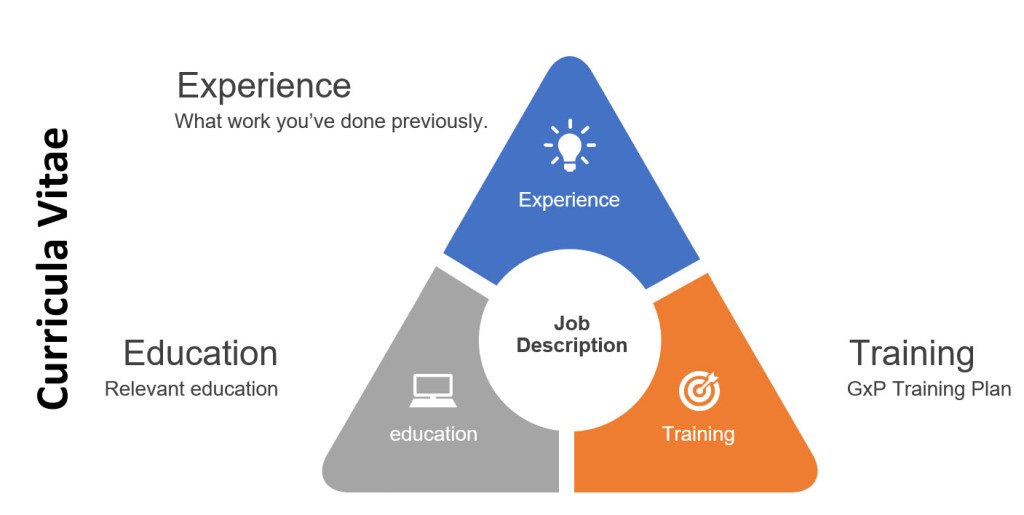

Job descriptions are foundational documents in pharmaceutical quality systems. Regulations like 21 CFR 211.25 require that personnel have appropriate education, training, and experience to perform assigned functions. The job description serves as the starting point for determining training requirements, establishing accountability, and demonstrating regulatory compliance. Yet for all their regulatory necessity, most job descriptions fail to capture what actually makes someone effective in their role.

The problem isn’t that job descriptions are poorly written or inadequately detailed. The problem is more fundamental: they describe static snapshots of isolated positions while ignoring the dynamic, interconnected, and discretionary nature of real organizational work.

The Static Job Description Trap

Traditional job descriptions treat roles as if they exist in isolation. A quality manager’s job description might list responsibilities like “lead inspection readiness activities,” “participate in vendor management,” or “write and review deviations and CAPAs”. These statements aren’t wrong, but they’re profoundly incomplete.

Elliott Jacques, a late 20th century thinker on organizational theory, identified a critical distinction that most job descriptions ignore: the difference between prescribed elements and discretionary elements of work. Every role contains both, yet our documentation acknowledge only one.

Prescribed elements are the boundaries, constraints, and requirements that eliminate choice. They specify what must be done, what cannot be done, and the regulations, policies, and methods to which the role holder must conform. In pharmaceutical quality, prescribed elements are abundant and well-documented: follow GMPs, complete training before performing tasks, document decisions according to procedure, escalate deviations within defined timeframes.

Discretionary elements are everything else—the choices, judgments, and decisions that cannot be fully specified in advance. They represent the exercise of professional judgment within the prescribed limits. Discretion is where competence actually lives.

When we investigate a deviation, the prescribed elements are clear: follow the investigation procedure, document findings in the system, complete within regulatory timelines. But the discretionary elements determine whether the investigation succeeds: What questions should I ask? Which subject matter experts should I engage? How deeply should I probe this particular failure mode? What level of evidence is sufficient? When have I gathered enough data to draw conclusions?

As Jacques observed, “the core of industrial work is therefore not only to carry out the prescribed elements of the job, but also to exercise discretion in its execution”. Yet if job descriptions don’t recognize and define the limits of discretion, employees will either fail to exercise adequate discretion or wander beyond appropriate limits into territory that belongs to other roles.

The Interconnectedness Problem

Job descriptions also fail because they treat positions as independent entities rather than as nodes in an organizational network. In reality, all jobs in pharmaceutical organizations are interconnected. A mistake in manufacturing manifests as a quality investigation. A poorly written procedure creates training challenges. An inadequate risk assessment during tech transfer generates compliance findings during inspection.

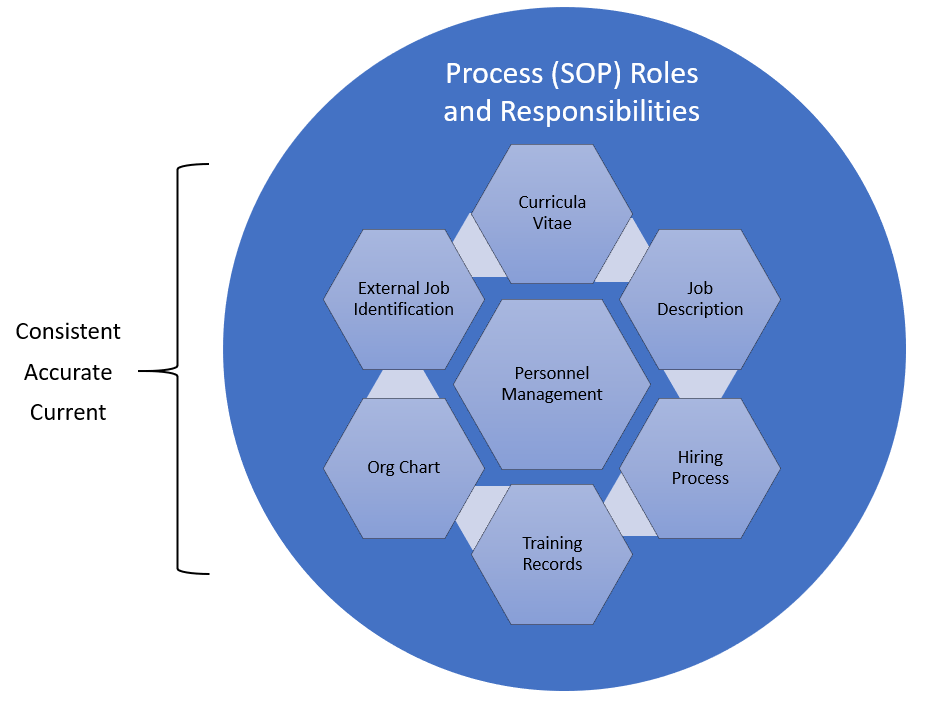

This interconnectedness means that describing any role in isolation fundamentally misrepresents how work actually flows through the organization. When I write about process owners, I emphasize that they play a fundamental role in managing interfaces between key processes precisely to prevent horizontal silos. The process owner’s authority and accountability extend across functional boundaries because the work itself crosses those boundaries.

Yet traditional job descriptions remain trapped in functional silos. They specify reporting relationships vertically—who you report to, who reports to you—but rarely acknowledge the lateral dependencies that define how work actually gets done. They describe individual accountability without addressing mutual obligations.

The Missing Element: Mutual Role Expectations

Jacques argued that effective job descriptions must contain three elements:

- The central purpose and rationale for the position

- The prescribed and discretionary elements of the work

- The mutual role expectations—what the focal role expects from other roles, and vice versa

That third element is almost entirely absent from job descriptions, yet it’s arguably the most critical for organizational effectiveness.

Consider a deviation investigation. The person leading the investigation needs certain things from other roles: timely access to manufacturing records from operations, technical expertise from subject matter experts, root cause methodology support from quality systems specialists, regulatory context from regulatory affairs. Conversely, those other roles have legitimate expectations of the quality professional: clear articulation of information needs, respect for operational constraints, transparency about investigation progress, appropriate use of their expertise.

These mutual expectations form the actual working contract that determines whether the organization functions effectively. When they remain implicit and undocumented, we get the dysfunction I see constantly: investigations that stall because operations claims they’re too busy to provide information, subject matter experts who feel blindsided by last-minute requests, quality professionals frustrated that other functions don’t understand the urgency of compliance timelines.

Decision-making frameworks like DACI and RAPID exist precisely to make these mutual expectations explicit. They clarify who drives decisions, who must be consulted, who has approval authority, and who needs to be informed. But these frameworks work at the decision level. We need the same clarity at the role level, embedded in how we define positions from the start.

Discretion and Hierarchy

The amount of discretion in a role—what Jacques called the “time span of discretion”—is actually a better measure of organizational level than traditional hierarchical markers like job titles or reporting relationships. A front-line operator works within tightly prescribed limits with short time horizons: follow this batch record, use these materials, execute these steps, escalate these deviations immediately. A site quality director operates with much broader discretion over longer time horizons: establish quality strategy, allocate resources across competing priorities, determine which regulatory risks to accept or mitigate, shape organizational culture over years.

This observation has profound implications for how we think about organizational design. As I’ve written before, the idea that “the higher the rank in the organization the more decision-making authority you have” is absurd. In every organization I’ve worked in, people hold positions of authority over areas where they lack the education, experience, and training to make competent decisions.

The solution isn’t to eliminate hierarchy—organizations need stratification by complexity and time horizon. The solution is to separate positional authority from decision authority and to explicitly define the discretionary scope of each role.

A manufacturing supervisor might have positional authority over operations staff but should not have decision authority over validation strategies—that’s outside their discretionary scope. A quality director might have positional authority over the quality function but should not unilaterally decide equipment qualification approaches that require deep engineering expertise. Clear boundaries around discretion prevent the territorial conflicts and competence gaps that plague organizations.

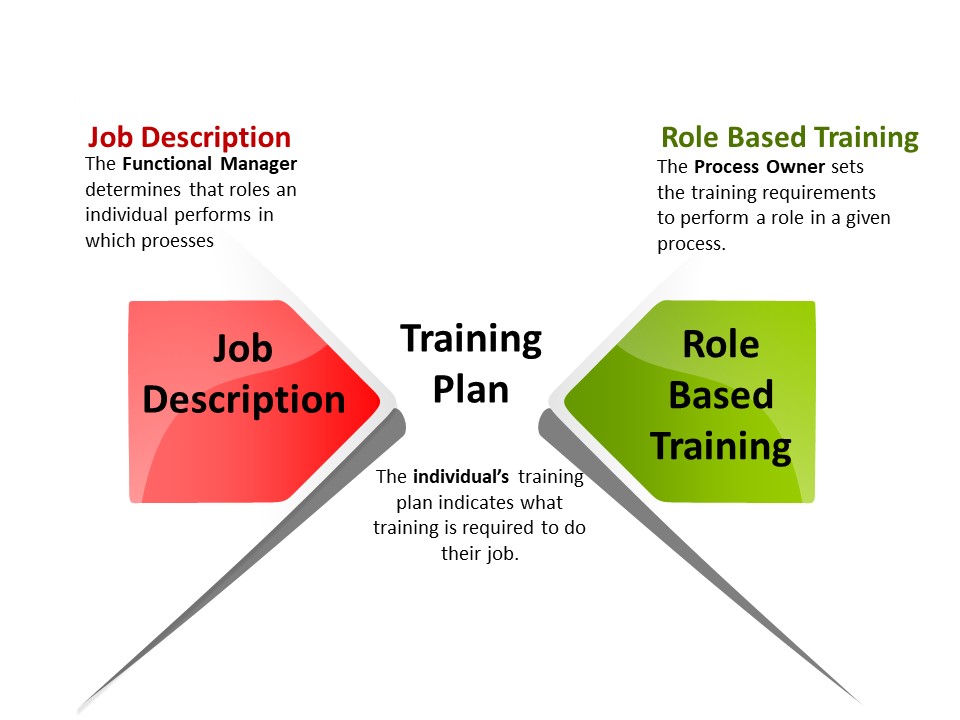

Implications for Training and Competency

The distinction between prescribed and discretionary elements has critical implications for how we develop competency. Most pharmaceutical training focuses almost exclusively on prescribed elements: here’s the procedure, here’s how to use the system, here’s what the regulation requires. We measure training effectiveness by knowledge checks that assess whether people remember the prescribed limits.

But competence isn’t about following procedures—it’s about exercising appropriate judgment within procedural constraints. It’s about knowing what to do when things depart from expectations, recognizing which risk assessment methodology fits a particular decision context, sensing when additional expertise needs to be consulted.

These discretionary capabilities develop differently than procedural knowledge. They require practice, feedback, coaching, and sustained engagement over time. A meta-analysis examining skill retention found that complex cognitive skills like risk assessment decay much faster than simple procedural skills. Without regular practice, the discretionary capabilities that define competence actively degrade.

This is why I emphasize frequency, duration, depth, and accuracy of practice as the real measures of competence. It’s why deep process ownership requires years of sustained engagement rather than weeks of onboarding. It’s why competency frameworks must integrate skills, knowledge, and behaviors in ways that acknowledge the discretionary nature of professional work.

Job descriptions that specify only prescribed elements provide no foundation for developing the discretionary capabilities that actually determine whether someone can perform the role effectively. They lead to training plans focused on knowledge transfer rather than judgment development, performance evaluations that measure compliance rather than contribution, and hiring decisions based on credentials rather than capacity.

Designing Better Job Descriptions

Quality leaders—especially those of us responsible for organizational design—need to fundamentally rethink how we define and document roles. Effective job descriptions should:

- Articulate the central purpose. Why does this role exist? What job is the organization hiring this position to do? A deviation investigator exists to transform quality failures into organizational learning while demonstrating control to regulators. A validation engineer exists to establish documented evidence that systems consistently produce quality outcomes. Purpose provides the context for exercising discretion appropriately.

- Specify prescribed boundaries explicitly. What are the non-negotiable constraints? Which policies, regulations, and procedures must be followed without exception? What decisions require escalation or approval? Clear prescribed limits create safety—they tell people where they can’t exercise judgment and where they must seek guidance.

- Define discretionary scope clearly. Within the prescribed limits, what decisions is this role expected to make independently? What level of evidence is this role qualified to evaluate? What types of problems should this role resolve without escalation? How much resource commitment can this role authorize? Making discretion explicit transforms vague “good judgment” expectations into concrete accountability.

- Document mutual role expectations. What does this role need from other roles to be successful? What do other roles have the right to expect from this position? How do the prescribed and discretionary elements of this role interface with adjacent roles in the process? Mapping these interdependencies makes the organizational system visible and manageable.

- Connect to process roles explicitly. Rather than generic statements like “participate in CAPAs,” job descriptions should specify process roles: “Author and project manage CAPAs for quality system improvements” or “Provide technical review of manufacturing-related CAPAs”. Process roles define the specific prescribed and discretionary elements relevant to each procedure. They provide the foundation for role-based training curricula that address both procedural compliance and judgment development.

Beyond Job Descriptions: Organizational Design

The limitations of traditional job descriptions point to larger questions about organizational design. If we’re serious about building quality systems that work—that don’t just satisfy auditors but actually prevent failures and enable learning—we need to design organizations around how work flows rather than how authority is distributed.

This means establishing empowered process owners who have clear authority over end-to-end processes regardless of functional boundaries. It means implementing decision-making frameworks that explicitly assign decision roles based on competence rather than hierarchy. It means creating conditions for deep process ownership through sustained engagement rather than rotational assignments.

Most importantly, it means recognizing that competent performance requires both adherence to prescribed limits and skillful exercise of discretion. Training systems, performance management approaches, and career development pathways must address both dimensions. Job descriptions that acknowledge only one while ignoring the other set employees up for failure and organizations up for dysfunction.

The Path Forward

Jacques wrote that organizational structures should be “requisite”—required by the nature of work itself rather than imposed by arbitrary management preferences. There’s wisdom in that framing for pharmaceutical quality. Our organizational structures should emerge from the actual requirements of pharmaceutical work: the need for both compliance and innovation, the reality of interdependent processes, the requirement for expert judgment alongside procedural discipline.

Job descriptions are foundational documents in quality systems. They link to hiring decisions, training requirements, performance expectations, and regulatory demonstration of competence. Getting them right matters not just for audit preparedness but for organizational effectiveness.

The next time you review a job description, ask yourself: Does this document acknowledge both what must be done and what must be decided? Does it clarify where discretion is expected and where it’s prohibited? Does it make visible the interdependencies that determine whether this role can succeed? Does it provide a foundation for developing both procedural compliance and professional judgment?

If the answer is no, you’re not alone. Most job descriptions fail these tests. But recognizing the deficit is the first step toward designing organizational systems that actually match the complexity and interdependence of pharmaceutical work—systems where competence can develop, accountability is clear, and quality is built into how we organize rather than inspected into what we produce.

The work of pharmaceutical quality requires us to exercise discretion well within prescribed limits. Our organizational design documents should acknowledge that reality rather than pretend it away.

Example Job Description

Site Quality Risk Manager – Seattle and Redmond Sites

Reports To: Sr. Manager, Quality

Department: Qualty

Location: Hybrid/Field-Based – Certain Sites

Purpose of the Role

The Site Quality Risk Manager ensures that quality and manufacturing operations at the sites maintain proactive, compliant, and science-based risk management practices. The role exists to translate uncertainty into structured understanding—identifying, prioritizing, and mitigating risks to product quality, patient safety, and business continuity. Through expert application of Quality Risk Management (QRM) principles, this role builds a culture of curiosity, professional judgment, and continuous improvement in decision-making.

Prescribed Work Elements

Boundaries and required activities defined by regulations, procedures, and PQS expectations.

- Ensure full alignment of the site Risk Program with the Corporate Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS), ICH Q9(R1) principles, and applicable GMP regulations.

- Facilitate and document formal quality risk assessments for manufacturing, laboratory, and facility operations.

- Manage and maintain the site Risk Registers for sitefacilities.

- Communicate high-priority risks, mitigation actions, and risk acceptance decisions to site and functional senior management.

- Support Health Authority inspections and audits as QRM Subject Matter Expert (SME).

- Lead deployment and sustainment of QRM process tools, templates, and governance structures within the corporate risk management framework.

- Maintain and periodically review site-level guidance documents and procedures on risk management.

Discretionary Work Elements

Judgment and decision-making required within professional and policy boundaries.

- Determine the appropriate depth and scope of risk assessments based on formality and system impact.

- Evaluate the adequacy and proportionality of mitigations, balancing regulatory conservatism with operational feasibility.

- Prioritize site risk topics requiring cross-functional escalation or systemic remediation.

- Shape site-specific applications of global QRM tools (e.g., HACCP, FMEA, HAZOP, RRF) to reflect manufacturing complexity and lifecycle phase—from Phase 1 through PPQ and commercial readiness.

- Determine which emerging risks require systemic visibility in the Corporate Risk Register and document rationale for inclusion or deferral.

- Facilitate reflection-based learning after deviations, applying risk communication as a learning mechanism across functions.

- Offer informed judgment in gray areas where quality principles must guide rather than prescribe decisions.

Mutual Role Expectations

From the Site Quality Risk Manager:

- Partner transparently with Process Owners and Functional SMEs to identify, evaluate, and mitigate risks.

- Translate technical findings into business-relevant risk statements for senior leadership.

- Mentor and train site teams to develop risk literacy and discretionary competence—the ability to think, not just comply.

- Maintain a systems perspective that integrates manufacturing, analytical, and quality operations within a unified risk framework.

From Other Roles Toward the Site Quality Risk Manager:

- Provide timely, complete data for risk assessments.

- Engage in collaborative dialogue rather than escalation-only interactions.

- Respect QRM governance boundaries while contributing specialized technical judgment.

- Support implementation of sustainable mitigations beyond short-term containment.

Qualifications and Experience

- Bachelor’s degree in life sciences, engineering, or a related technical discipline. Equivalent experience accepted.

- Minimum 4+ years relevant experience in Quality Risk Management within biopharmaceutical GMP manufacturing environments.

- Demonstrated application of QRM methodologies (FMEA, HACCP, HAZOP, RRF) and facilitation of cross-functional risk assessments.

- Strong understanding of ICH Q9(R1) and FDA/EMA risk management expectations.

- Proven ability to make judgment-based decisions under regulatory and operational uncertainty.

- Experience mentoring or building risk capabilities across technical teams.

- Excellent communication, synthesis, and facilitation skills.

Purpose in Organizational Design Context

This role exemplifies a requisite position—where scope of discretion, not hierarchy, defines level of work. The Site Quality Risk Manager operates with a medium-span time horizon (6–18 months), balancing regulatory compliance with strategic foresight. Success is measured by the organization’s capacity to detect, understand, and manage risk at progressively earlier stages of product and process lifecycle—reducing reactivity and enabling resilience.

Competency Development and Training Focus

- Prescribed competence: Deep mastery of PQS procedures, regulatory standards, and risk methodologies.

- Discretionary competence: Situational judgment, cross-functional influence, systems thinking, and adaptive decision-making.

Training plans should integrate practice, feedback, and reflection mechanisms rather than static knowledge transfer, aligning with the competency framework principles.

This enriched job description demonstrates how clarity of purpose, articulation of prescribed vs. discretionary elements, and defined mutual expectations transform a standard compliance document into a true instrument of organizational design and leadership alignment.