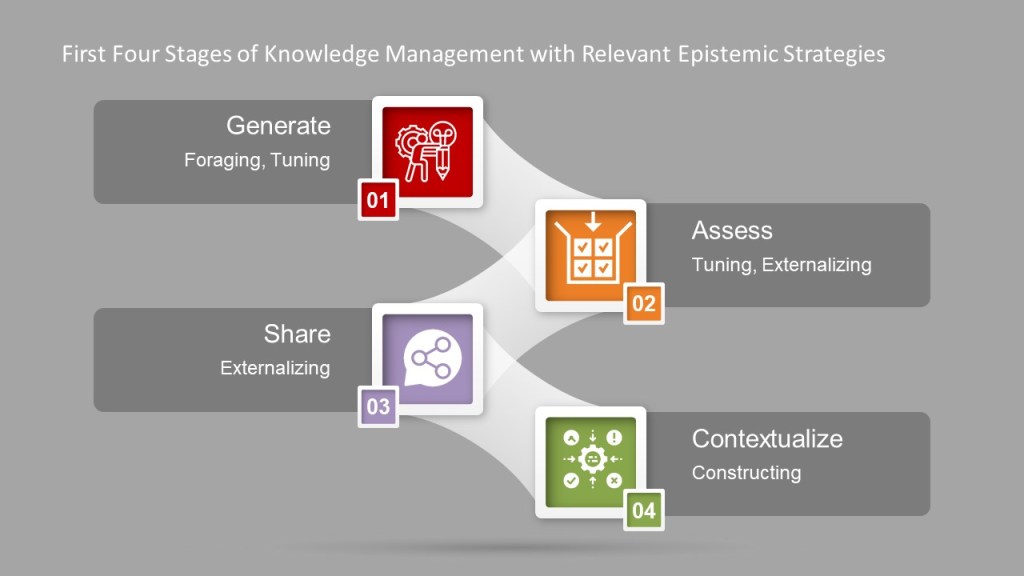

The first four phases of knowledge management are all about identifying and creating meaning and then making that meaning usable. Knowledge management is a set of epistemic actions, creating knowledge through interaction. This interaction is a way of creating a partnership between what happens in the head with everything in the world – Work-as-Imagined and Work-as-Done.

There are really four themes to a set of epistemic actions:

- Foraging: Locating resources that will lead to understanding

- Tuning: Adjusting resources to align with desired understanding

- Externalizing: Moving resources out of the head and into the world

- Constructing: Forming new knowledge structures in the world

These epistemic actions are all about moving from Work-as-Imagined through Work-as-Prescribed to enable Work-as-Done.

Knowledge Management is really about the embodiment of information, knowledge, and even wisdom through these epistemic actions to apply change upon the world.

|

Theme |

Epistemic Interaction |

Means |

|

Foraging Locating resources that will lead to understanding |

Searching

|

Searching happens when you need information and believe it exists somewhere. Searching depends on how we articulate or information needs. |

|

Probing

|

“Tell me more.” Probing happens when the information you have isn’t quite enough. You are probing when you take the next step, move to the next level, and obtain more salient specifics. Probing is about drilling down and saying “show, explain, and reveal more about this.” We can probe to reveal new patterns, structures and relationships. It brings to light new information that helps us to reconsider what we already know. |

|

|

Animating

|

Animating is when we initiate and control motion in an information source. It includes learning-by-doing. |

|

|

Collecting |

Collecting is how we gather foraged information and tuck it away for future use. |

|

|

Tuning Adjusting resources to align with desired understanding |

Collecting

|

|

|

Cloning

|

Cloning lets us take information from one situation and use it in another. |

|

|

Cutting

|

Cutting is the way we say “this matters”, that “I need this part, but not the rest.” |

|

|

Filtering |

Filtering reduces complexity by reducing clutter to expose salient details. |

|

|

Externalizing Moving resources out of the head and into the world |

Annotating

|

Annotating is how we add context to information. How we adapt and modify the information to the needed context. |

|

Linking |

Connecting bits of information together. Forming conceptual maps. |

|

|

Generating |

Introducing new knowledge into the world. |

|

|

Chunking |

Grouping idenpendent yet related information together. |

|

|

Constructing Forming new knowledge structures in the world |

Chunking

|

|

|

Composing |

Producing a new, separate structure from the information that has its own meaning and purpose. |

|

|

Fragmenting |

Taking information and breaking it apart into usable components. |

|

|

Rearranging |

The art of creating meaningful order. |

|

|

Repicturing |

Changing the way the information is represented to create understanding. |