We are at a fascinating and pivotal moment in standardizing Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) across the pharmaceutical industry. The recently released draft ICH M15 guideline, alongside the European Medicines Agency’s evolving framework for mechanistic models and the FDA’s draft guidance on artificial intelligence applications, establishes comprehensive expectations for implementing, evaluating, and documenting computational approaches in drug development. As these regulatory frameworks mature, understanding the nuanced requirements for mechanistic modeling becomes essential for successful drug development and regulatory acceptance.

The Spectrum of Mechanistic Models in Pharmaceutical Development

Mechanistic models represent a distinct category within the broader landscape of Model-Informed Drug Development, distinguished by their incorporation of underlying physiological, biological, or physical principles. Unlike purely empirical approaches that describe relationships within observed data without explaining causality, mechanistic models attempt to represent the actual processes driving those observations. These models facilitate extrapolation beyond observed data points and enable prediction across diverse scenarios that may not be directly observable in clinical studies.

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Models

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models incorporate anatomical, physiological, and biochemical information to simulate drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion processes. These models typically represent the body as a series of interconnected compartments corresponding to specific organs or tissues, with parameters reflecting physiological properties such as blood flow, tissue volumes, and enzyme expression levels. For example, a PBPK model might be used to predict the impact of hepatic impairment on drug clearance by adjusting liver blood flow and metabolic enzyme expression parameters to reflect pathophysiological changes. Such models are particularly valuable for predicting drug exposures in special populations (pediatric, geriatric, or disease states) where conducting extensive clinical trials might be challenging or ethically problematic.

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology Models

Quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) models integrate pharmacokinetics with pharmacodynamic mechanisms at the systems level, incorporating feedback mechanisms and homeostatic controls. These models typically include detailed representations of biological pathways and drug-target interactions. For instance, a QSP model for an immunomodulatory agent might capture the complex interplay between different immune cell populations, cytokine signaling networks, and drug-target binding dynamics. This approach enables prediction of emergent properties that might not be apparent from simpler models, such as delayed treatment effects or rebound phenomena following drug discontinuation. The ICH M15 guideline specifically acknowledges the value of QSP models for integrating knowledge across different biological scales and predicting outcomes in scenarios where data are limited.

Agent-Based Models

Agent-based models simulate the actions and interactions of autonomous entities (agents) to assess their effects on the system as a whole. In pharmaceutical applications, these models are particularly useful for infectious disease modeling or immune system dynamics. For example, an agent-based model might represent individual immune cells and pathogens as distinct agents, each following programmed rules of behavior, to simulate the immune response to a vaccine. The emergent patterns from these individual interactions can provide insights into population-level responses that would be difficult to capture with more traditional modeling approaches5.

Disease Progression Models

Disease progression models mathematically represent the natural history of a disease and how interventions might modify its course. These models incorporate time-dependent changes in biomarkers or clinical endpoints related to the underlying pathophysiology. For instance, a disease progression model for Alzheimer’s disease might include parameters representing the accumulation of amyloid plaques, neurodegeneration rates, and cognitive decline, allowing simulation of how disease-modifying therapies might alter the trajectory of cognitive function over time. The ICH M15 guideline recognizes the value of these models for characterizing long-term treatment effects that may not be directly observable within the timeframe of clinical trials.

Applying the MIDD Evidence Assessment Framework to Mechanistic Models

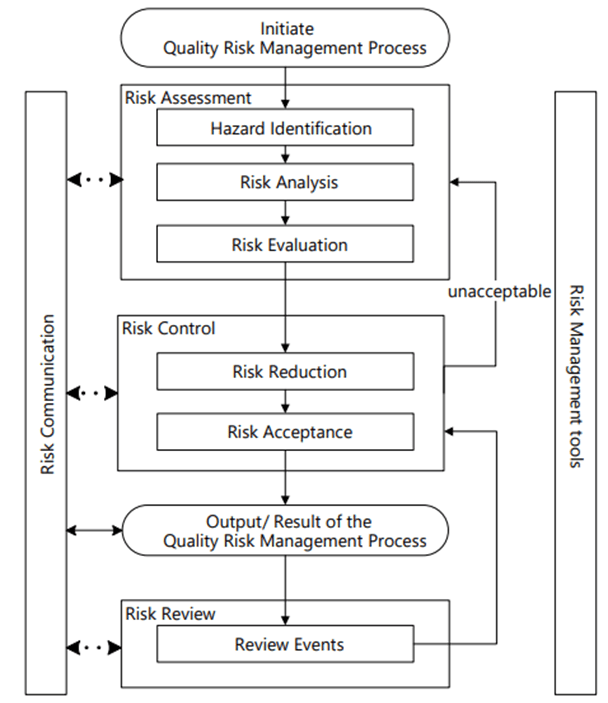

The ICH M15 guideline introduces a structured framework for assessment of MIDD evidence, which applies across modeling methodologies but requires specific considerations for mechanistic models. This framework centers around several key elements that must be clearly defined and assessed to establish the credibility of model-based evidence.

Defining Questions of Interest and Context of Use

For mechanistic models, precisely defining the Question of Interest is particularly important due to their complexity and the numerous assumptions embedded within their structure. According to the ICH M15 guideline, the Question of Interest should “describe the specific objective of the MIDD evidence” in a concise manner. For example, a Question of Interest for a PBPK model might be: “What is the appropriate dose adjustment for patients with severe renal impairment?” or “What is the expected magnitude of a drug-drug interaction when Drug A is co-administered with Drug B?”

The Context of Use must provide a clear description of the model’s scope, the data used in its development, and how the model outcomes will contribute to answering the Question of Interest. For mechanistic models, this typically includes explicit statements about the physiological processes represented, assumptions regarding system behavior, and the intended extrapolation domain. For instance, the Context of Use for a QSP model might specify: “The model will be used to predict the time course of viral load reduction following administration of a novel antiviral therapy at doses ranging from 10 to 100 mg in treatment-naïve adult patients with hepatitis C genotype 1.”

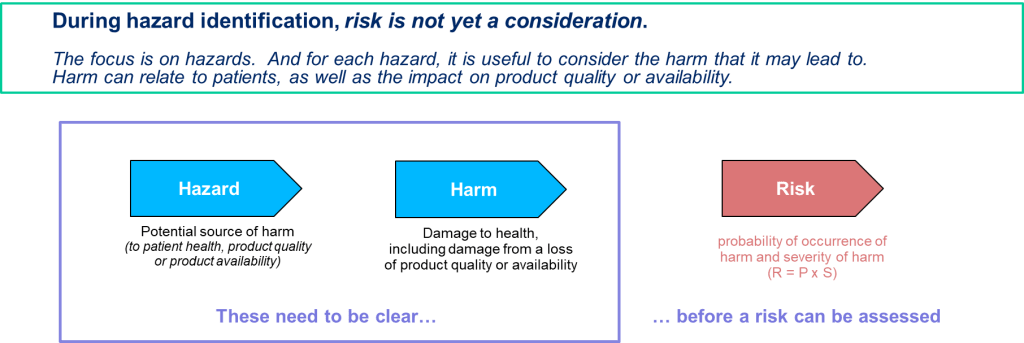

Conducting Model Risk and Impact Assessment

Model Risk assessment combines the Model Influence (the weight of model outcomes in decision-making) with the Consequence of Wrong Decision (potential impact on patient safety or efficacy). For mechanistic models, the Model Influence is often high due to their ability to simulate conditions that cannot be directly observed in clinical trials. For example, if a PBPK model is being used as the primary evidence to support a dosing recommendation in a specific patient population without confirmatory clinical data, its influence would be rated as “high.”

The Consequence of Wrong Decision should be assessed based on potential impacts on patient safety and efficacy. For instance, if a mechanistic model is being used to predict drug exposures in pediatric patients for a drug with a narrow therapeutic index, the consequence of an incorrect prediction could be significant adverse events or treatment failure, warranting a “high” rating.

Model Impact reflects the contribution of model outcomes relative to current regulatory expectations or standards. For novel mechanistic modeling approaches, the Model Impact may be high if they are being used to replace traditionally required clinical studies or inform critical labeling decisions. The assessment table provided in Appendix 1 of the ICH M15 guideline serves as a practical tool for structuring this evaluation and facilitating communication with regulatory authorities.

Comprehensive Approach to Uncertainty Quantification in Mechanistic Models

Uncertainty quantification (UQ) is the science of quantitative characterization and estimation of uncertainties in both computational and real-world applications. It aims to determine how likely certain outcomes are when aspects of the system are not precisely known. For mechanistic models, this process is particularly crucial due to their complexity and the numerous assumptions embedded within their structure. A comprehensive uncertainty quantification approach is essential for establishing model credibility and supporting regulatory decision-making.

Types of Uncertainty in Mechanistic Models

Understanding the different sources of uncertainty is the first step toward effectively quantifying and communicating the limitations of model predictions. In mechanistic modeling, uncertainty typically stems from three primary sources:

Parameter Uncertainty

Parameter uncertainty emerges from imprecise knowledge of model parameters that serve as inputs to the mathematical model. These parameters may be unknown, variable, or cannot be precisely inferred from available data. In physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models, parameter uncertainty might include tissue partition coefficients, enzyme expression levels, or membrane permeability values. For example, the liver-to-plasma partition coefficient for a lipophilic drug might be estimated from in vitro measurements but carry considerable uncertainty due to experimental variability or limitations in the in vitro system’s representation of in vivo conditions.

Parametric Uncertainty

Parametric uncertainty derives from the variability of input variables across the target population. In the context of drug development, this might include demographic factors (age, weight, ethnicity), genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism, or disease states that influence drug disposition or response. For instance, the activity of CYP3A4, a major drug-metabolizing enzyme, can vary up to 20-fold among individuals due to genetic, environmental, and physiological factors. This variability introduces uncertainty when predicting drug clearance in a diverse patient population.

Structural Uncertainty

Structural uncertainty, also known as model inadequacy or model discrepancy, results from incomplete knowledge of the underlying biology or physics. It reflects the gap between the mathematical representation and the true biological system. For example, a PBPK model might assume first-order kinetics for a metabolic pathway that actually exhibits more complex behavior at higher drug concentrations, or a QSP model might omit certain feedback mechanisms that become relevant under specific conditions. Structural uncertainty is often the most challenging type to quantify because it represents “unknown unknowns” in our understanding of the system.

Profile Likelihood Analysis for Parameter Identifiability and Uncertainty

Profile likelihood analysis has emerged as an efficient tool for practical identifiability analysis of mechanistic models, providing a systematic approach to exploring parameter uncertainty and identifiability issues. This approach involves fixing one parameter at various values across a range of interest while optimizing all other parameters to obtain the best possible fit to the data. The resulting profile of likelihood (or objective function) values reveals how well the parameter is constrained by the available data.

According to recent methodological developments, profile likelihood analysis provides equivalent verdicts concerning identifiability orders of magnitude faster than other approaches, such as Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). The methodology involves the following steps:

- Selecting a parameter of interest (θi) and a range of values to explore

- For each value of θi, optimizing all other parameters to minimize the objective function

- Recording the optimized objective function value to construct the profile

- Repeating for all parameters of interest

The resulting profiles enable several key analyses:

- Construction of confidence intervals representing overall uncertainties

- Identification of non-identifiable parameters (flat profiles)

- Attribution of the influence of specific parameters on predictions

- Exploration of correlations between parameters (linked identifiability)

For example, when applying profile likelihood analysis to a mechanistic model of drug absorption with parameters for dissolution rate, permeability, and gut transit time, the analysis might reveal that while dissolution rate and permeability are individually non-identifiable (their individual values cannot be uniquely determined), their product is well-defined. This insight helps modelers understand which parameter combinations are constrained by the data and where additional experiments might be needed to reduce uncertainty.

Monte Carlo Simulation for Uncertainty Propagation

Monte Carlo simulation provides a powerful approach for propagating uncertainty from model inputs to outputs. This technique involves randomly sampling from probability distributions representing parameter uncertainty, running the model with each sampled parameter set, and analyzing the resulting distribution of outputs. The process comprises several key steps:

- Defining probability distributions for uncertain parameters based on available data or expert knowledge

- Generating random samples from these distributions, accounting for correlations between parameters

- Running the model for each sampled parameter set

- Analyzing the resulting output distributions to characterize prediction uncertainty

For example, in a PBPK model of a drug primarily eliminated by CYP3A4, the enzyme abundance might be represented by a log-normal distribution with parameters derived from population data. Monte Carlo sampling from this and other relevant distributions (e.g., organ blood flows, tissue volumes) would generate thousands of virtual individuals, each with a physiologically plausible parameter set. The model would then be simulated for each virtual individual to produce a distribution of predicted drug exposures, capturing the expected population variability and parameter uncertainty.

To ensure robust uncertainty quantification, the number of Monte Carlo samples must be sufficient to achieve stable estimates of output statistics. The Monte Carlo Error (MCE), defined as the standard deviation of the Monte Carlo estimator, provides a measure of the simulation precision and can be estimated using bootstrap resampling. For critical regulatory applications, it is important to demonstrate that the MCE is small relative to the overall output uncertainty, confirming that simulation imprecision is not significantly influencing the conclusions.

Sensitivity Analysis Techniques

Sensitivity analysis quantifies how changes in model inputs influence the outputs, helping to identify the parameters that contribute most significantly to prediction uncertainty. Several approaches to sensitivity analysis are particularly valuable for mechanistic models:

Local Sensitivity Analysis

Local sensitivity analysis examines how small perturbations in input parameters affect model outputs, typically by calculating partial derivatives at a specific point in parameter space. For mechanistic models described by ordinary differential equations (ODEs), sensitivity equations can be derived directly from the model equations and solved alongside the original system. Local sensitivities provide valuable insights into model behavior around a specific parameter set but may not fully characterize the effects of larger parameter variations or interactions between parameters.

Global Sensitivity Analysis

Global sensitivity analysis explores the full parameter space, accounting for non-linearities and interactions that local methods might miss. Variance-based methods, such as Sobol indices, decompose the output variance into contributions from individual parameters and their interactions. These methods require extensive sampling of the parameter space but provide comprehensive insights into parameter importance across the entire range of uncertainty.

Tornado Diagrams for Visualizing Parameter Influence

Tornado diagrams offer a straightforward visualization of parameter sensitivity, showing how varying each parameter within its uncertainty range affects a specific model output. These diagrams rank parameters by their influence, with the most impactful parameters at the top, creating the characteristic “tornado” shape. For example, a tornado diagram for a PBPK model might reveal that predicted maximum plasma concentration is most sensitive to absorption rate constant, followed by clearance and volume of distribution, while other parameters have minimal impact. This visualization helps modelers and reviewers quickly identify the critical parameters driving prediction uncertainty.

Step-by-Step Uncertainty Quantification Process

Implementing comprehensive uncertainty quantification for mechanistic models requires a structured approach. The following steps provide a detailed guide to the process:

- Parameter Uncertainty Characterization:

- Compile available data on parameter values and variability

- Estimate probability distributions for each parameter

- Account for correlations between parameters

- Document data sources and distribution selection rationale

- Model Structural Analysis:

- Identify key assumptions and simplifications in the model structure

- Assess potential alternative model structures

- Consider multiple model structures if structural uncertainty is significant

- Identifiability Analysis:

- Perform profile likelihood analysis for key parameters

- Identify practical and structural non-identifiabilities

- Develop strategies to address non-identifiable parameters (e.g., fixing to literature values, reparameterization)

- Global Uncertainty Propagation:

- Define sampling strategy for Monte Carlo simulation

- Generate parameter sets accounting for correlations

- Execute model simulations for all parameter sets

- Calculate summary statistics and confidence intervals for model outputs

- Sensitivity Analysis:

- Conduct global sensitivity analysis to identify key uncertainty drivers

- Create tornado diagrams for critical model outputs

- Explore parameter interactions through advanced sensitivity methods

- Documentation and Communication:

- Clearly document all uncertainty quantification methods

- Present results using appropriate visualizations

- Discuss implications for decision-making

- Acknowledge limitations in the uncertainty quantification approach

For regulatory submissions, this process should be documented in the Model Analysis Plan (MAP) and Model Analysis Report (MAR), with particular attention to the methods used to characterize parameter uncertainty, the approach to sensitivity analysis, and the interpretation of uncertainty in model predictions.

Case Example: Uncertainty Quantification for a PBPK Model

To illustrate the practical application of uncertainty quantification, consider a PBPK model developed to predict drug exposures in patients with hepatic impairment. The model includes parameters representing physiological changes in liver disease (reduced hepatic blood flow, decreased enzyme expression, altered plasma protein binding) and drug-specific parameters (intrinsic clearance, tissue partition coefficients).

Parameter uncertainty is characterized based on literature data, with hepatic blood flow in cirrhotic patients represented by a log-normal distribution (mean 0.75 L/min, coefficient of variation 30%) and enzyme expression by a similar distribution (mean 60% of normal, coefficient of variation 40%). Drug-specific parameters are derived from in vitro experiments, with intrinsic clearance following a normal distribution centered on the mean experimental value with standard deviation reflecting experimental variability.

Profile likelihood analysis reveals that while total hepatic clearance is well-identified from available pharmacokinetic data, separating the contributions of blood flow and intrinsic clearance is challenging. This insight suggests that predictions of clearance changes in hepatic impairment might be robust despite uncertainty in the underlying mechanisms.

Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 parameter sets generates a distribution of predicted concentration-time profiles. The results indicate that in severe hepatic impairment, drug exposure (AUC) is expected to increase 3.2-fold (90% confidence interval: 2.1 to 4.8-fold) compared to healthy subjects. Sensitivity analysis identifies hepatic blood flow as the primary contributor to prediction uncertainty, followed by intrinsic clearance and plasma protein binding.

This comprehensive uncertainty quantification supports a dosing recommendation to reduce the dose by 67% in severe hepatic impairment, with the understanding that therapeutic drug monitoring might be advisable given the wide confidence interval in the predicted exposure increase.

Model Structure and Identifiability in Mechanistic Modeling

The selection of model structure represents a critical decision in mechanistic modeling that directly impacts the model’s predictive capabilities and limitations. For regulatory acceptance, both the conceptual and mathematical structure must be justified based on current scientific understanding of the underlying biological processes.

Determining Appropriate Model Structure

Model structure should be consistent with available knowledge on drug characteristics, pharmacology, physiology, and disease pathophysiology. The level of complexity should align with the Question of Interest – incorporating sufficient detail to capture relevant phenomena while avoiding unnecessary complexity that could introduce additional uncertainty.

Key structural aspects to consider include:

- Compartmentalization (e.g., lumped vs. physiologically-based compartments)

- Rate processes (e.g., first-order vs. saturable kinetics)

- System boundaries (what processes are included vs. excluded)

- Time scales (what temporal dynamics are captured)

For example, when modeling the pharmacokinetics of a highly lipophilic drug with slow tissue distribution, a model structure with separate compartments for poorly and well-perfused tissues would be appropriate to capture the delayed equilibration with adipose tissue. In contrast, for a hydrophilic drug with rapid distribution, a simpler structure with fewer compartments might be sufficient. The selection should be justified based on the drug’s physicochemical properties and observed pharmacokinetic behavior.

Comprehensive Identifiability Analysis

Identifiability refers to the ability to uniquely determine the values of model parameters from available data. This concept is particularly important for mechanistic models, which often contain numerous parameters that may not all be directly observable.

Two forms of non-identifiability can occur:

- Structural non-identifiability: When the model structure inherently prevents unique parameter determination, regardless of data quality

- Practical non-identifiability: When limitations in the available data (quantity, quality, or information content) prevent precise parameter estimation

Profile likelihood analysis provides a reliable and efficient approach for identifiability assessment of mechanistic models. This methodology involves systematically varying individual parameters while re-optimizing all others, generating profiles that visualize parameter identifiability and uncertainty.

For example, in a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model, structural non-identifiability might arise if the model includes separate parameters for the fraction absorbed and bioavailability, but only plasma concentration data is available. Since these parameters appear as a product in the equations governing plasma concentrations, they cannot be uniquely identified without additional data (e.g., portal vein sampling or intravenous administration for comparison).

Practical non-identifiability might occur if a parameter’s influence on model outputs is small relative to measurement noise, or if sampling times are not optimally designed to inform specific parameters. For instance, if blood sampling times are concentrated in the distribution phase, parameters governing terminal elimination might not be practically identifiable despite being structurally identifiable.

For regulatory submissions, identifiability analysis should be documented, with particular attention to parameters critical for the model’s intended purpose. Non-identifiable parameters should be acknowledged, and their potential impact on predictions should be assessed through sensitivity analyses.

Regulatory Requirements for Data Quality and Relevance

Regulatory authorities place significant emphasis on the quality and relevance of data used in mechanistic modeling. The ICH M15 guideline provides specific recommendations regarding data considerations for model development and evaluation.

Data Quality Standards and Documentation

Data used for model development and validation should adhere to appropriate quality standards, with consideration of the data’s intended use within the modeling context. For data derived from clinical studies, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) standards typically apply, while non-clinical data should comply with Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) when appropriate.

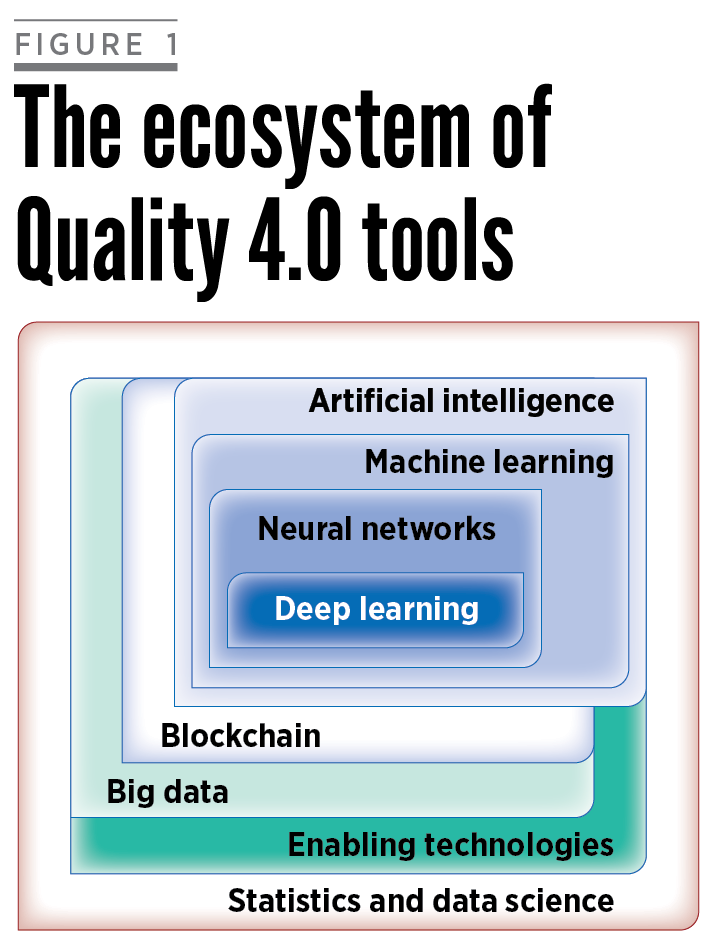

The FDA guidance on AI in drug development emphasizes that data should be “fit for use,” meaning it should be both relevant (including key data elements and sufficient representation) and reliable (accurate, complete, and traceable). This concept applies equally to mechanistic models, particularly those incorporating AI components for parameter estimation or data integration.

Documentation of data provenance, collection methods, and any processing or transformation steps is essential. For literature-derived data, the selection criteria, extraction methods, and assessment of quality should be transparently reported. For example, when using published clinical trial data to develop a population pharmacokinetic model, modelers should document:

- Search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria for study selection

- Extraction methods for relevant data points

- Assessment of study quality and potential biases

- Methods for handling missing data or reconciling inconsistencies across studies

This comprehensive documentation enables reviewers to assess whether the data foundation of the model is appropriate for its intended regulatory use.

Data Relevance Assessment for Target Populations

The relevance and appropriateness of data to answer the Question of Interest must be justified. This includes consideration of:

- Population characteristics relative to the target population

- Study design features (dosing regimens, sampling schedules, etc.)

- Bioanalytical methods and their sensitivity/specificity

- Environmental or contextual factors that might influence results

For example, when developing a mechanistic model to predict drug exposures in pediatric patients, data relevance considerations might include:

- Age distribution of existing pediatric data compared to the target age range

- Developmental factors affecting drug disposition (e.g., ontogeny of metabolic enzymes)

- Body weight and other anthropometric measures relevant to scaling

- Disease characteristics if the target population has a specific condition

The rationale for any data exclusion should be provided, and the potential for selection bias should be assessed. Data transformations and imputations should be specified, justified, and documented in the Model Analysis Plan (MAP) and Model Analysis Report (MAR).

Data Management Systems for Regulatory Compliance

Effective data management is increasingly important for regulatory compliance in model-informed approaches. Financial institutions have been required to overhaul their risk management processes with greater reliance on data, providing detailed reports to regulators on the risks they face and their impact on their capital and liquidity positions. Similar expectations are emerging in pharmaceutical development.

A robust data management system should be implemented that enables traceability from raw data to model inputs, with appropriate version control and audit trails. This system should include:

- Data collection and curation protocols

- Quality control procedures

- Documentation of data transformations and aggregations

- Tracking of data version used for specific model iterations

- Access controls to ensure data integrity

This comprehensive data management approach ensures that mechanistic models are built on a solid foundation of high-quality, relevant data that can withstand regulatory scrutiny.

Model Development and Evaluation: A Comprehensive Approach

The ICH M15 guideline outlines a comprehensive approach to model evaluation through three key elements: verification, validation, and applicability assessment. These elements collectively determine the acceptability of the model for answering the Question of Interest and form the basis of MIDD evidence assessment.

Verification Procedures for Mechanistic Models

Verification activities aim to ensure that user-generated codes for processing data and conducting analyses are error-free, equations reflecting model assumptions are correctly implemented, and calculations are accurate. For mechanistic models, verification typically involves:

- Code verification: Ensuring computational implementation correctly represents the mathematical model through:

- Code review by qualified personnel

- Unit testing of individual model components

- Comparison with analytical solutions for simplified cases

- Benchmarking against established implementations when available

- Solution verification: Confirming numerical solutions are sufficiently accurate by:

- Assessing sensitivity to solver settings (e.g., time step size, tolerance)

- Demonstrating solution convergence with refined numerical parameters

- Implementing mass balance checks for conservation laws

- Verifying steady-state solutions where applicable

- Calculation verification: Checking that derived quantities are correctly calculated through:

- Independent recalculation of key metrics

- Verification of dimensional consistency

- Cross-checking outputs against simplified calculations

For example, verification of a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model implemented in a custom software platform might include comparing numerical solutions against analytical solutions for simple cases (e.g., one-compartment models), demonstrating mass conservation across compartments, and verifying that area under the curve (AUC) calculations match direct numerical integration of concentration-time profiles.

Validation Strategies for Mechanistic Models

Validation activities assess the adequacy of model robustness and performance. For mechanistic models, validation should address:

- Conceptual validation: Ensuring the model structure aligns with current scientific understanding by:

- Reviewing the biological basis for model equations

- Assessing mechanistic plausibility of parameter values

- Confirming alignment with established scientific literature

- Mathematical validation: Confirming the equations appropriately represent the conceptual model through:

- Dimensional analysis to ensure physical consistency

- Bounds checking to verify physiological plausibility

- Stability analysis to identify potential numerical issues

- Predictive validation: Evaluating the model’s ability to predict observed outcomes by:

- Comparing predictions to independent data not used in model development

- Assessing prediction accuracy across diverse scenarios

- Quantifying prediction uncertainty and comparing to observed variability

Model performance should be assessed using both graphical and numerical metrics, with emphasis on those most relevant to the Question of Interest. For example, validation of a QSP model for predicting treatment response might include visual predictive checks comparing simulated and observed biomarker trajectories, calculation of prediction errors for key endpoints, and assessment of the model’s ability to reproduce known drug-drug interactions or special population effects.

External Validation: The Gold Standard

External validation with independent data is particularly valuable for mechanistic models and can substantially increase confidence in their applicability. This involves testing the model against data that was not used in model development or parameter estimation. The strength of external validation depends on the similarity between the validation dataset and the intended application domain.

For example, a metabolic drug-drug interaction model developed using data from healthy volunteers might be externally validated using:

- Data from a separate clinical study with different dosing regimens

- Observations from patient populations not included in model development

- Real-world evidence collected in post-marketing settings

The results of external validation should be documented with the same rigor as the primary model development, including clear specification of validation criteria and quantitative assessment of prediction performance.

Applicability Assessment for Regulatory Decision-Making

Applicability characterizes the relevance and adequacy of the model’s contribution to answering a specific Question of Interest. This assessment should consider:

- The alignment between model scope and the Question of Interest:

- Does the model include all relevant processes?

- Are the included mechanisms sufficient to address the question?

- Are simplifying assumptions appropriate for the intended use?

- The appropriateness of model assumptions for the intended application:

- Are physiological parameter values representative of the target population?

- Do the mechanistic assumptions hold under the conditions being simulated?

- Has the model been tested under conditions similar to the intended application?

- The validity of extrapolations beyond the model’s development dataset:

- Is extrapolation based on established scientific principles?

- Have similar extrapolations been previously validated?

- Is the degree of extrapolation reasonable given model uncertainty?

For example, applicability assessment for a PBPK model being used to predict drug exposures in pediatric patients might evaluate whether:

- The model includes age-dependent changes in physiological parameters

- Enzyme ontogeny profiles are supported by current scientific understanding

- The extrapolation from adult to pediatric populations relies on well-established scaling principles

- The degree of extrapolation is reasonable given available pediatric pharmacokinetic data for similar compounds

Detailed Plan for Meeting Regulatory Requirements

A comprehensive plan for ensuring regulatory compliance should include detailed steps for model development, evaluation, and documentation. The following expanded approach provides a structured pathway to meet regulatory expectations:

- Development of a comprehensive Model Analysis Plan (MAP):

- Clear articulation of the Question of Interest and Context of Use

- Detailed description of data sources, including quality assessments

- Comprehensive inclusion/exclusion criteria for literature-derived data

- Justification of model structure with reference to biological mechanisms

- Detailed parameter estimation strategy, including handling of non-identifiability

- Comprehensive verification, validation, and applicability assessment approaches

- Specific technical criteria for model evaluation, with acceptance thresholds

- Detailed simulation methodologies, including virtual population generation

- Uncertainty quantification approach, including sensitivity analysis methods

- Implementation of rigorous verification activities:

- Systematic code review by qualified personnel not involved in code development

- Unit testing of all computational components with documented test cases

- Integration testing of the complete modeling workflow

- Verification of numerical accuracy through comparison with analytical solutions

- Mass balance checking for conservation laws

- Comprehensive documentation of all verification procedures and results

- Execution of multi-faceted validation activities:

- Systematic evaluation of data relevance and quality for model development

- Comprehensive assessment of parameter identifiability using profile likelihood

- Detailed sensitivity analyses to determine parameter influence on key outputs

- Comparison of model predictions against development data with statistical assessment

- External validation against independent datasets

- Evaluation of predictive performance across diverse scenarios

- Assessment of model robustness to parameter uncertainty

- Comprehensive documentation in a Model Analysis Report (MAR):

- Executive summary highlighting key findings and conclusions

- Detailed introduction establishing scientific and regulatory context

- Clear statement of objectives aligned with Questions of Interest

- Comprehensive description of data sources and quality assessment

- Detailed explanation of model structure with scientific justification

- Complete documentation of parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification

- Comprehensive results of model development and evaluation

- Thorough discussion of limitations and their implications

- Clear conclusions regarding model applicability for the intended purpose

- Complete references and supporting materials

- Preparation of targeted regulatory submission materials:

- Completion of the assessment table from ICH M15 Appendix 1 with detailed justifications

- Development of concise summaries for inclusion in regulatory documents

- Preparation of responses to anticipated regulatory questions

- Organization of supporting materials (MAPs, MARs, code, data) for submission

- Development of visual aids to communicate model structure and results effectively

This detailed approach ensures alignment with regulatory expectations while producing robust, scientifically sound mechanistic models suitable for drug development decision-making.

Virtual Population Generation and Simulation Scenarios

The development of virtual populations and the design of simulation scenarios represent critical aspects of mechanistic modeling that directly impact the relevance and reliability of model predictions. Proper design and implementation of these elements are essential for regulatory acceptance of model-based evidence.

Developing Representative Virtual Populations

Virtual population models serve as digital representations of human anatomical and physiological variability. The Virtual Population (ViP) models represent one prominent example, consisting of detailed high-resolution anatomical models created from magnetic resonance image data of volunteers.

For mechanistic modeling in drug development, virtual populations should capture relevant demographic, physiological, and genetic characteristics of the target patient population. Key considerations include:

- Population parameters and their distributions: Demographic variables (age, weight, height) and physiological parameters (organ volumes, blood flows, enzyme expression levels) should be represented by appropriate statistical distributions derived from population data. For example, liver volume might follow a log-normal distribution with parameters estimated from anatomical studies, while CYP enzyme expression might follow similar distributions with parameters derived from liver bank data.

- Correlations between parameters: Physiological parameters are often correlated (e.g., body weight correlates with organ volumes and cardiac output), and these correlations must be preserved to ensure physiological plausibility. Correlation structures can be implemented using techniques such as copulas or multivariate normal distributions with specified correlation matrices.

- Special populations: When modeling special populations (pediatric, geriatric, renal/hepatic impairment), the virtual population should reflect the specific physiological changes associated with these conditions. For pediatric populations, this includes age-dependent changes in body composition, organ maturation, and enzyme ontogeny. For disease states, the relevant pathophysiological changes should be incorporated, such as reduced glomerular filtration rate in renal impairment or altered hepatic blood flow in cirrhosis.

- Genetic polymorphisms: For drugs metabolized by enzymes with known polymorphisms (e.g., CYP2D6, CYP2C19), the virtual population should include the relevant frequency distributions of these genetic variants. This enables prediction of exposure variability and identification of potential high-risk subpopulations.

For example, a virtual population for evaluating a drug primarily metabolized by CYP2D6 might include subjects across the spectrum of metabolizer phenotypes: poor metabolizers (5-10% of Caucasians), intermediate metabolizers (10-15%), extensive metabolizers (65-80%), and ultrarapid metabolizers (5-10%). The physiological parameters for each group would be adjusted to reflect the corresponding enzyme activity levels, allowing prediction of drug exposure across phenotypes and evaluation of potential dose adjustment requirements.

Designing Informative Simulation Scenarios

Simulation scenarios should be designed to address specific questions while accounting for parameter and assumption uncertainties. Effective simulation design requires careful consideration of several factors:

- Clear definition of simulation objectives aligned with the Question of Interest: Simulation objectives should directly support the regulatory question being addressed. For example, if the Question of Interest relates to dose selection for a specific patient population, simulation objectives might include characterizing exposure distributions across doses, identifying factors influencing exposure variability, and determining the proportion of patients achieving target exposure levels.

- Comprehensive specification of treatment regimens: Simulation scenarios should include all relevant aspects of the treatment protocol, such as dose levels, dosing frequency, administration route, and duration. For complex regimens (loading doses, titration, maintenance), the complete dosing algorithm should be specified. For example, a simulation evaluating a titration regimen might include scenarios with different starting doses, titration criteria, and dose adjustment magnitudes.

- Strategic sampling designs: Sampling strategies should be specified to match the clinical setting being simulated. This includes sampling times, measured analytes (parent drug, metabolites), and sampling compartments (plasma, urine, tissue). For exposure-response analyses, the sampling design should capture the relationship between pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects.

- Incorporation of relevant covariates and their influence: Simulation scenarios should explore the impact of covariates known or suspected to influence drug behavior. This includes demographic factors (age, weight, sex), physiological variables (renal/hepatic function), concomitant medications, and food effects. For example, a comprehensive simulation plan might include scenarios for different age groups, renal function categories, and with/without interacting medications.

For regulatory submissions, simulation methods and scenarios should be described in sufficient detail to enable evaluation of their plausibility and relevance. This includes justification of the simulation approach, description of virtual subject generation, and explanation of analytical methods applied to simulation results.

Fractional Factorial Designs for Efficient Simulation

When the simulation is intended to represent a complex trial with multiple factors, “fractional” or “response surface” designs are often appropriate, as they provide an efficient way to examine relationships between multiple factors and outcomes. These designs enable maximum reliability from the resources devoted to the project and allow examination of individual and joint impacts of numerous factors.

For example, a simulation exploring the impact of renal impairment, age, and body weight on drug exposure might employ a fractional factorial design rather than simulating all possible combinations. This approach strategically samples the multidimensional parameter space to provide comprehensive insights with fewer simulation runs.

The design and analysis of such simulation studies should follow established principles of experiment design, including:

- Proper randomization to avoid systematic biases

- Balanced allocation across factor levels when appropriate

- Statistical power calculations to determine required simulation sample sizes

- Appropriate statistical methods for analyzing multifactorial results

These approaches maximize the information obtained from simulation studies while maintaining computational efficiency, providing robust evidence for regulatory decision-making.

Best Practices for Reporting Results of Mechanistic Modeling and Simulation

Effective communication of mechanistic modeling results is essential for regulatory acceptance and scientific credibility. The ICH M15 guideline and related regulatory frameworks provide specific recommendations for documentation and reporting that apply directly to mechanistic models.

Structured Documentation Through Model Analysis Plans and Reports

Predefined Model Analysis Plans (MAPs) should document the planned analyses, including objectives, data sources, modeling methods, and evaluation criteria. For mechanistic models, MAPs should additionally specify:

- The biological basis for the model structure, with reference to current scientific understanding and literature support

- Detailed description of model equations and their mechanistic interpretation

- Sources and justification for physiological parameters, including population distributions

- Comprehensive approach for addressing parameter uncertainty

- Specific methods for evaluating predictive performance, including acceptance criteria

Results should be documented in Model Analysis Reports (MARs) following the structure outlined in Appendix 2 of the ICH M15 guideline. A comprehensive MAR for a mechanistic model should include:

- Executive Summary: Concise overview of the modeling approach, key findings, and conclusions relevant to the regulatory question

- Introduction: Detailed background on the drug, mechanism of action, and scientific context for the modeling approach

- Objectives: Clear statement of modeling goals aligned with specific Questions of Interest

- Data and Methods: Comprehensive description of:

- Data sources, quality assessment, and relevance evaluation

- Detailed model structure with mechanistic justification

- Parameter estimation approach and results

- Uncertainty quantification methodology

- Verification and validation procedures

- Results: Detailed presentation of:

- Model development process and parameter estimates

- Uncertainty analysis results, including parameter confidence intervals

- Sensitivity analysis identifying key drivers of model behavior

- Validation results with statistical assessment of predictive performance

- Simulation outcomes addressing the specific regulatory questions

- Discussion: Thoughtful interpretation of results, including:

- Mechanistic insights gained from the modeling

- Comparison with previous knowledge and expectations

- Limitations of the model and their implications

- Uncertainty in predictions and its regulatory impact

- Conclusions: Assessment of model adequacy for the intended purpose and specific recommendations for regulatory decision-making

- References and Appendices: Supporting information, including detailed results, code documentation, and supplementary analyses

Assessment Tables for Regulatory Communication

The assessment table from ICH M15 Appendix 1 provides a structured format for communicating key aspects of the modeling approach. For mechanistic models, this table should clearly specify:

- Question of Interest: Precise statement of the regulatory question being addressed

- Context of Use: Detailed description of the model scope and intended application

- Model Influence: Assessment of how heavily the model evidence weighs in the overall decision-making

- Consequence of Wrong Decision: Evaluation of potential impacts on patient safety and efficacy

- Model Risk: Combined assessment of influence and consequences, with justification

- Model Impact: Evaluation of the model’s contribution relative to regulatory expectations

- Technical Criteria: Specific metrics and thresholds for evaluating model adequacy

- Model Evaluation: Summary of verification, validation, and applicability assessment results

- Outcome Assessment: Overall conclusion regarding the model’s fitness for purpose

This structured communication facilitates regulatory review by clearly linking the modeling approach to the specific regulatory question and providing a transparent assessment of the model’s strengths and limitations.

Transparency, Completeness, and Parsimony in Reporting

Reporting of mechanistic modeling should follow principles of transparency, completeness, and parsimony. As stated in guidance for simulation in drug development:

- CLARITY: The report should be understandable in terms of scope and conclusions by intended users

- COMPLETENESS: Assumptions, methods, and critical results should be described in sufficient detail to be reproduced by an independent team

- PARSIMONY: The complexity of models and simulation procedures should be no more than necessary to meet the objectives

For simulation studies specifically, reporting should address all elements of the ADEMP framework (Aims, Data-generating mechanisms, Estimands, Methods, and Performance measures).

The ADEMP Framework for Simulation Studies

The ADEMP framework represents a structured approach for planning, conducting, and reporting simulation studies in a comprehensive and transparent manner. Introduced by Morris, White, and Crowther in their seminal 2019 paper published in Statistics in Medicine, this framework has rapidly gained traction across multiple disciplines including biostatistics. ADEMP provides a systematic methodology that enhances the credibility and reproducibility of simulation studies while facilitating clearer communication of complex results.

Components of the ADEMP Framework

Aims

The Aims component explicitly defines the purpose and objectives of the simulation study. This critical first step establishes what questions the simulation intends to answer and provides context for all subsequent decisions. For example, a clear aim might be “to evaluate the hypothesis testing and estimation characteristics of different methods for analyzing pre-post measurements”. Well-articulated aims guide the entire simulation process and help readers understand the context and relevance of the results.

Data-generating Mechanism

The Data-generating mechanism describes precisely how datasets are created for the simulation. This includes specifying the underlying probability distributions, sample sizes, correlation structures, and any other parameters needed to generate synthetic data. For instance, pre-post measurements might be “simulated from a bivariate normal distribution for two groups, with varying treatment effects and pre-post correlations”. This component ensures that readers understand the conditions under which methods are being evaluated and can assess whether these conditions reflect scenarios relevant to their research questions.

Estimands and Other Targets

Estimands refer to the specific parameters or quantities of interest that the simulation aims to estimate or test. This component defines what “truth” is known in the simulation and what aspects of this truth the methods should recover or address. For example, “the null hypothesis of no effect between groups is the primary target, the treatment effect is the secondary estimand of interest”. Clear definition of estimands allows for precise evaluation of method performance relative to known truth values.

Methods

The Methods component details which statistical techniques or approaches will be evaluated in the simulation. This should include sufficient technical detail about implementation to ensure reproducibility. In a simulation comparing approaches to pre-post measurement analysis, methods might include ANCOVA, change-score analysis, and post-score analysis. The methods section should also specify software, packages, and key parameter settings used for implementation.

Performance Measures

Performance measures define the metrics used to evaluate and compare the methods being assessed. These metrics should align with the stated aims and estimands of the study. Common performance measures include Type I error rate, power, and bias among others. This component is crucial as it determines how results will be interpreted and what conclusions can be drawn about method performance.

Importance of the ADEMP Framework

The ADEMP framework addresses several common shortcomings observed in simulation studies by providing a structured approach, ADEMP helps researchers:

- Plan simulation studies more rigorously before execution

- Document design decisions in a systematic manner

- Report results comprehensively and transparently

- Enable better assessment of the validity and generalizability of findings

- Facilitate reproduction and verification by other researchers

Implementation

When reporting simulation results using the ADEMP framework, researchers should:

- Present results clearly answering the main research questions

- Acknowledge uncertainty in estimated performance (e.g., through Monte Carlo standard errors)

- Balance between streamlined reporting and comprehensive detail

- Use effective visual presentations combined with quantitative summaries

- Avoid selectively reporting only favorable conditions

Visual Communication of Uncertainty

Effective communication of uncertainty is essential for proper interpretation of mechanistic model results. While tempting to present only point estimates, comprehensive reporting should include visual representations of uncertainty:

- Confidence/prediction intervals on key plots, such as concentration-time profiles or exposure-response relationships

- Forest plots showing parameter sensitivity and its impact on key outcomes

- Tornado diagrams highlighting the relative contribution of different uncertainty sources

- Boxplots or violin plots illustrating the distribution of simulated outcomes across virtual subjects

These visualizations help reviewers and decision-makers understand the robustness of conclusions and identify areas where additional data might be valuable.

Conclusion

The evolving regulatory landscape for Model-Informed Drug Development, as exemplified by the ICH M15 draft guideline, the EMA’s mechanistic model guidance initiative, and the FDA’s framework for AI applications, provides both structure and opportunity for the application of mechanistic models in pharmaceutical development. By adhering to the comprehensive frameworks for model evaluation, uncertainty quantification, and documentation outlined in these guidelines, modelers can enhance the credibility and impact of their work.

Mechanistic models offer unique advantages in their ability to integrate biological knowledge with clinical and non-clinical data, enabling predictions across populations, doses, and scenarios that may not be directly observable in clinical studies. However, these benefits come with responsibilities for rigorous model development, thorough uncertainty quantification, and transparent reporting.

The systematic approach described in this article—from clear articulation of modeling objectives through comprehensive validation to structured documentation—provides a roadmap for ensuring mechanistic models meet regulatory expectations while maximizing their value in drug development decision-making. As regulatory science continues to evolve, the principles outlined in ICH M15 and related guidance establish a foundation for consistent assessment and application of mechanistic models that will ultimately contribute to more efficient development of safe and effective medicines.