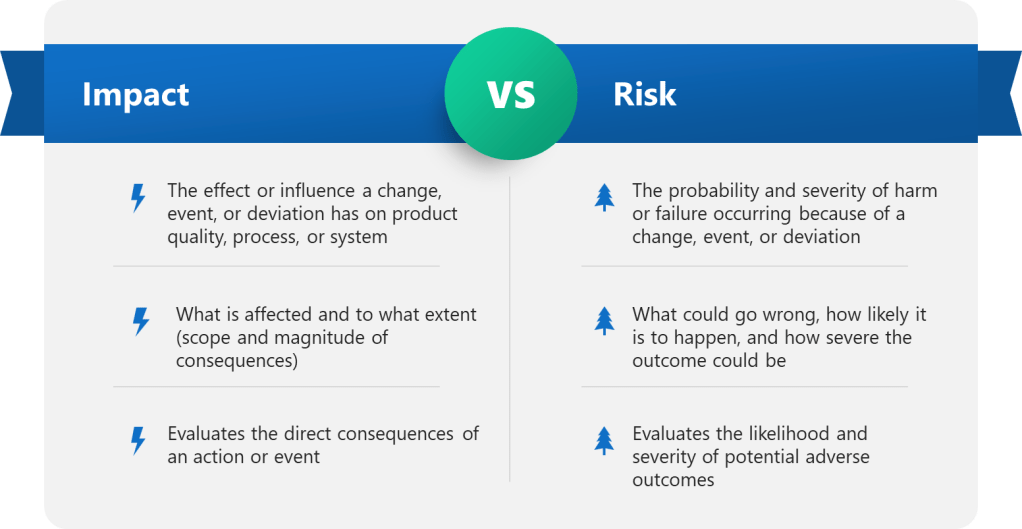

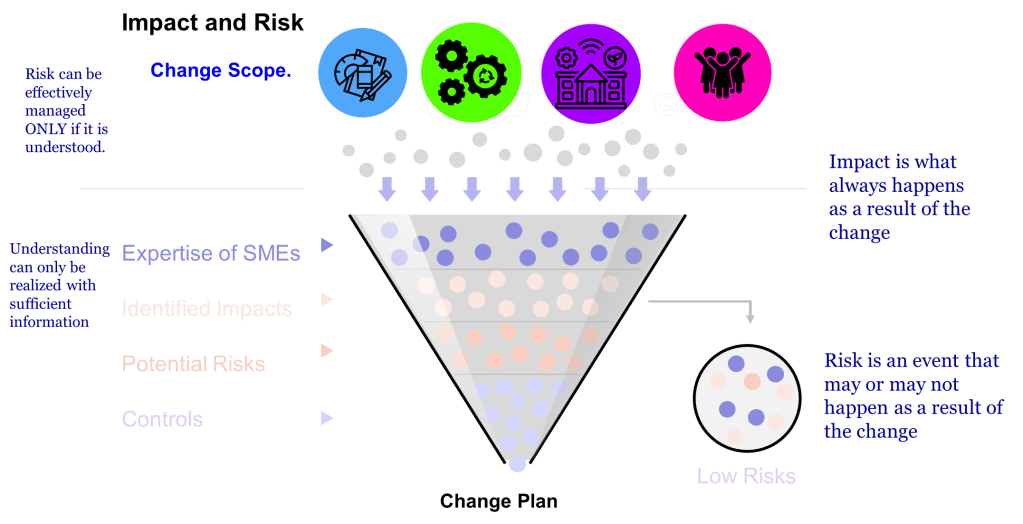

Two concepts—impact and risk — are often discussed but sometimes conflated within quality systems. While related, these concepts serve distinct purposes and drive different decisions throughout the quality system. Let’s explore.

The Fundamental Difference: Impact vs. Risk

The difference between impact and risk is fundamental to effective quality management. The difference between impact and risk is critical. Impact is best thought of as ‘What do I need to do to make the change.’ Risk is ‘What could go wrong in making this change?'”

Impact assessment focuses on evaluating the effects of a proposed change on various elements such as documentation, equipment, processes, and training. It helps identify the scope and reach of a change. Risk assessment, by contrast, looks ahead to identify potential failures that might occur due to the change – it’s preventive and focused on possible consequences.

This distinction isn’t merely academic – it directly affects how we approach actions and decisions in our quality systems, impacting core functions of CAPA, Change Control and Management Review.

| Aspect | Impact | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The effect or influence a change, event, or deviation has on product quality, process, or system | The probability and severity of harm or failure occurring as a result of a change, event, or deviation |

| Focus | What is affected and to what extent (scope and magnitude of consequences) | What could go wrong, how likely it is to happen, and how severe the outcome could be |

| Assessment Type | Evaluates the direct consequences of an action or event | Evaluates the likelihood and severity of potential adverse outcomes |

| Typical Use | Used in change control to determine which documents, systems, or processes are impacted | Used to prioritize actions, allocate resources, and implement controls to minimize negative outcomes |

| Measurement | Usually described qualitatively (e.g., minor, moderate, major, critical) | Often quantified by combining probability and impact scores to assign a risk level (e.g., low, medium, high) |

| Example | A change in raw material supplier impacts the manufacturing process and documentation. | The risk is that the new supplier’s material could fail to meet quality standards, leading to product defects. |

Change Control: Different Questions, Different Purposes

Within change management, the PIC/S Recommendation PI 054-1 notes that “In some cases, especially for simple and minor/low risk changes, an impact assessment is sufficient to document the risk-based rationale for a change without the use of more formal risk assessment tools or approaches.”

Impact Assessment in Change Control

- Determines what documentation requires updating

- Identifies affected systems, equipment, and processes

- Establishes validation requirements

- Determines training needs

Risk Assessment in Change Control

- Identifies potential failures that could result from the change

- Evaluates possible consequences to product quality and patient safety

- Determines likelihood of those consequences occurring

- Guides preventive measures

A common mistake is conflating these concepts or shortcutting one assessment. For example, companies often rush to designate changes as “like-for-like” without supporting data, effectively bypassing proper risk assessment. This highlights why maintaining the distinction is crucial.

Validation: Complementary Approaches

In validation, the impact-risk distinction shapes our entire approach.

Impact in validation relates to identifying what aspects of product quality could be affected by a system or process. For example, when qualifying manufacturing equipment, we determine which critical quality attributes (CQAs) might be influenced by the equipment’s performance.

Risk assessment in validation explores what could go wrong with the equipment or process that might lead to quality failures. Risk management plays a pivotal role in validation by enabling a risk-based approach to defining validation strategies, ensuring regulatory compliance, mitigating product quality and safety risks, facilitating continuous improvement, and promoting cross-functional collaboration.

In Design Qualification, we verify that the critical aspects (CAs) and critical design elements (CDEs) necessary to control risks identified during the quality risk assessment (QRA) are present in the design. This illustrates how impact assessment (identifying critical aspects) works together with risk assessment (identifying what could go wrong).

When we perform Design Review and Design Qualification, we focus on Critical Aspects: Prioritize design elements that directly impact product quality and patient safety. Here, impact assessment identifies critical aspects, while risk assessment helps prioritize based on potential consequences.

Following Design Qualification, Verification activities such as Installation Qualification (IQ), Operational Qualification (OQ), and Performance Qualification (PQ) serve to confirm that the system or equipment performs as intended under actual operating conditions. Here, impact assessment identifies the specific parameters and functions that must be verified to ensure no critical quality attributes are compromised. Simultaneously, risk assessment guides the selection and extent of tests by focusing on areas with the highest potential for failure or deviation. This dual approach ensures that verification not only confirms the intended impact of the design but also proactively mitigates risks before routine use.

Validation does not end with initial qualification. Continuous Validation involves ongoing monitoring and trending of process performance and product quality to confirm that the validated state is maintained over time. Impact assessment plays a role in identifying which parameters and quality attributes require ongoing scrutiny, while risk assessment helps prioritize monitoring efforts based on the likelihood and severity of potential deviations. This continuous cycle allows quality systems to detect emerging risks early and implement corrective actions promptly, reinforcing a proactive, risk-based culture that safeguards product quality throughout the product lifecycle.

Data Integrity: A Clear Example

Data integrity offers perhaps the clearest illustration of the impact-risk distinction.

As I’ve previously noted, Data quality is not a risk. It is a causal factor in the failure or severity. Poor data quality isn’t itself a risk; rather, it’s a factor that can influence the severity or likelihood of risks.

When assessing data integrity issues:

- Impact assessment identifies what data is affected and which processes rely on that data

- Risk assessment evaluates potential consequences of data integrity lapses

In my risk-based data integrity assessment methodology, I use a risk rating system that considers both impact and risk factors:

| Risk Rating | Action | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| >25 | High Risk-Potential Impact to Patient Safety or Product Quality | Mandatory |

| 12-25 | Moderate Risk-No Impact to Patient Safety or Product Quality but Potential Regulatory Risk | Recommended |

| <12 | Negligible DI Risk | Not Required |

This system integrates both impact (on patient safety or product quality) and risk (likelihood and detectability of issues) to guide mitigation decisions.

The Golden Day: Impact and Risk in Deviation Management

The Golden Day concept for deviation management provides an excellent practical example. Within the first 24 hours of discovering a deviation, we conduct:

- An impact assessment to determine:

- Which products, materials, or batches are affected

- Potential effects on critical quality attributes

- Possible regulatory implications

- A risk assessment to evaluate:

- Patient safety implications

- Product quality impact

- Compliance with registered specifications

- Level of investigation required

This impact assessment is also the initial risk assessment, which will help guide the level of effort put into the deviation. This statement shows how the two concepts, while distinct, work together to inform quality decisions.

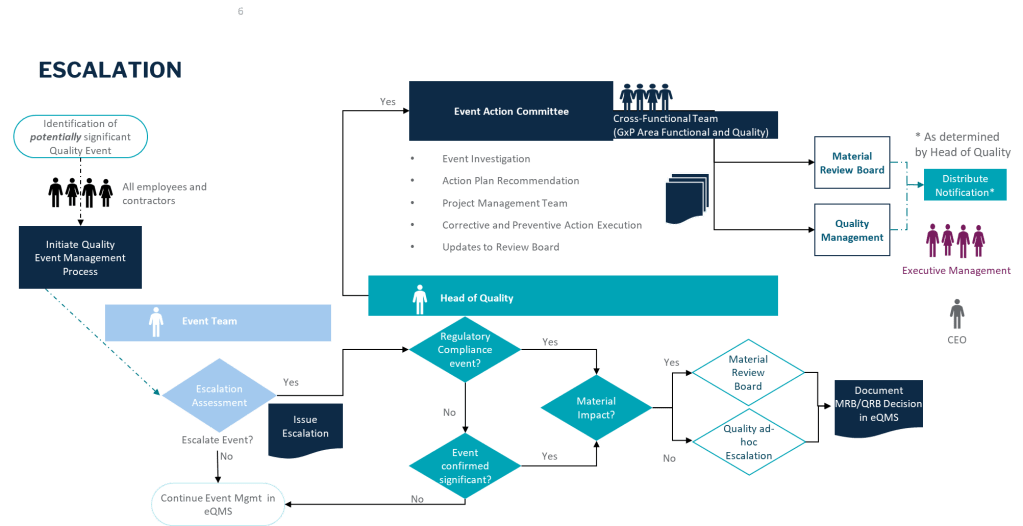

Quality Escalation: When Impact Triggers a Response

In quality escalation, we often use specific criteria based on both impact and risk:

| Escalation Criteria | Examples of Quality Events for Escalation |

|---|---|

| Potential to adversely affect quality, safety, efficacy, performance or compliance of product | – Contamination – Product defect/deviation from process parameters or specification – Significant GMP deviations |

| Product counterfeiting, tampering, theft | – Product counterfeiting, tampering, theft reportable to Health Authority – Lost/stolen IMP |

| Product shortage likely to disrupt patient care | – Disruption of product supply due to product quality events |

| Potential to cause patient harm associated with a product quality event | – Urgent Safety Measure, Serious Breach, Significant Product Complaint |

These criteria demonstrate how we use both impact (what’s affected) and risk (potential consequences) to determine when issues require escalation.

Both Are Essential

Understanding the difference between impact and risk fundamentally changes how we approach quality management. Impact assessment without risk assessment may identify what’s affected but fails to prevent potential issues. Risk assessment without impact assessment might focus on theoretical problems without understanding the actual scope.

The pharmaceutical quality system requires both perspectives:

- Impact tells us the scope – what’s affected

- Risk tells us the consequences – what could go wrong

By maintaining this distinction and applying both concepts appropriately across change control, validation, and data integrity management, we build more robust quality systems that not only comply with regulations but actually protect product quality and patient safety.