Single-use systems (SUS) have become increasingly prevalent in biopharmaceutical manufacturing due to their flexibility, reduced contamination risk, and cost-effectiveness. The thing is, management of the life-cycle of single-use systems becomes critical and is an area organizations can truly screw up by cutting corners. To do it right requires careful collaboration between all stakeholders in the supply chain, from raw material suppliers to end users.

Design and Development

Apply Quality by Design (QbD) principles from the outset by focusing on process understanding and the design space to create controlled and consistent manufacturing processes that result in high-quality, efficacious products. This approach should be applied to SUS design.

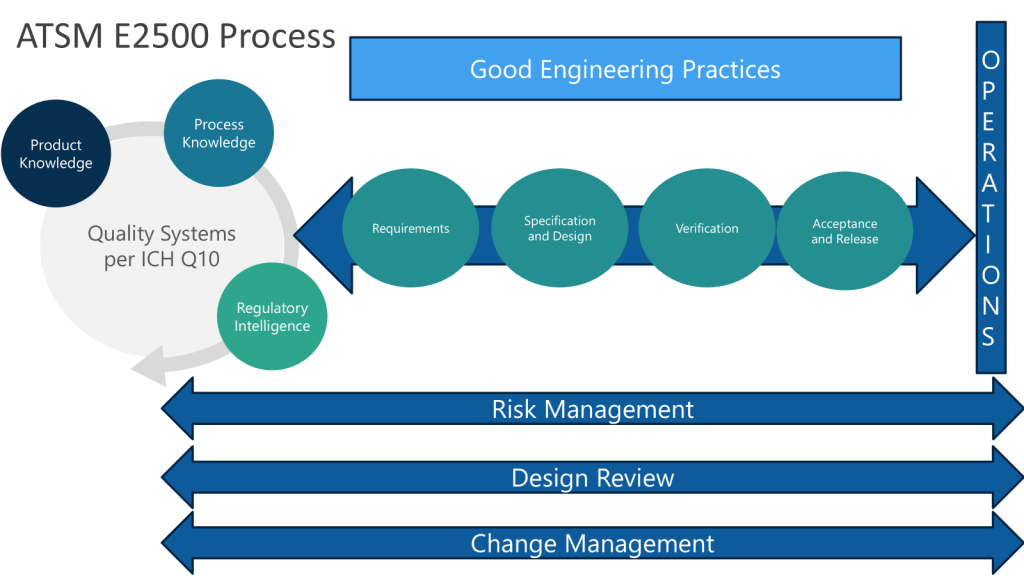

ASTM E3051 “Standard guide for specification, design, verification, and application of SUS in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturing” provides an excellent framework for the design process.

Make sure to conduct thorough risk assessments, considering potential failure modes and effects throughout the SUS life-cycle.

Engage end-users early to understand their specific requirements and process constraints. A real mistake in organizations is not involving the end-users early enough. From the molecule steward to manufacturing these users are critical.

Raw Material and Component Selection

Carefully evaluate and qualify raw materials and components. Work closely with suppliers to understand material properties, extractables/leachables profiles, and manufacturing processes.

Develop comprehensive specifications for critical materials and components. ASTM E3244 is handy place to look for guidance on raw material qualification for SUS.

Manage the Supplier through Manufacturing and Assembly

Implementing robust supplier qualification and auditing programs and establish change control agreements with suppliers to be notified of any changes that could impact SUS performance or quality. It is important the supplier have a robust quality management system and that they apply Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) through their facilities. Ensure they have in place appropriate controls to

- Validate sterilization processes

- Conduct routine bioburden and endotoxin testing

- Design packaging to protect SUS during transportation and storage. Shipping methods need to protect against physical damage and temperature excursions

- Establish appropriate storage conditions and shelf-life based on stability studies

- Provide appropriate labeling and traceability

- Have appropriate inventory controls. Ideally select suppliers who understand the importance of working with you for collaborative planning, forecasting and replenishment (CPFR)

Testing and Qualification

Develop a comprehensive testing strategy, including integrity testing and conduct extractables and leachables studies following industry guidelines. Evaluate the suppliers shipping and transportation studies to evaluate SUS robustness and determine if you need additional studies.

Implementation and Use

End users should have appropriate and comprehensive documentation and training to end users on proper handling, installation, and use of SUS. These procedures should include how to perform pre-use integrity testing at the point of use as well as how to perform thorough in-process and final inspections.

Consider implementing automated visual inspection systems and other appropriate monitoring.

Implement appropriate environmental monitoring programs in SUS manufacturing areas. While the dream of manufacturing outdoors is a good one, chances are we aren’t even close yet. Don’t short this layer of control.

Continuous Improvement

Ensure you have appropriate mechanisms in place to gather data on SUS performance and any issues encountered during use. Share relevant information across the supply chain to drive improvements.

Conduct periodic audits of suppliers and manufacturing facilities.

Stay updated on evolving regulatory guidance and industry best practices. There is still a lot changing in this space.