We have an unfortunate habit of conflating regulatory process requirements with specific system functionality requirements. This confusion manifests most perversely in User Requirements Specifications that contain nebulous statements like “the system shall comply with 21 CFR Part 11” or “the system must meet EU GMP Annex 11 requirements.” These high-level regulatory citations represent a fundamental misunderstanding of what user requirements should accomplish and demonstrate a dangerous abdication of the detailed thinking required for effective validation.

The core problem is simple yet profound: lifecycle, risk management, and validation are organizational processes, not system characteristics. When we embed these process-level concepts into system requirements, we create validation exercises that test compliance theater rather than functional reality.

The Distinction That Changes Everything

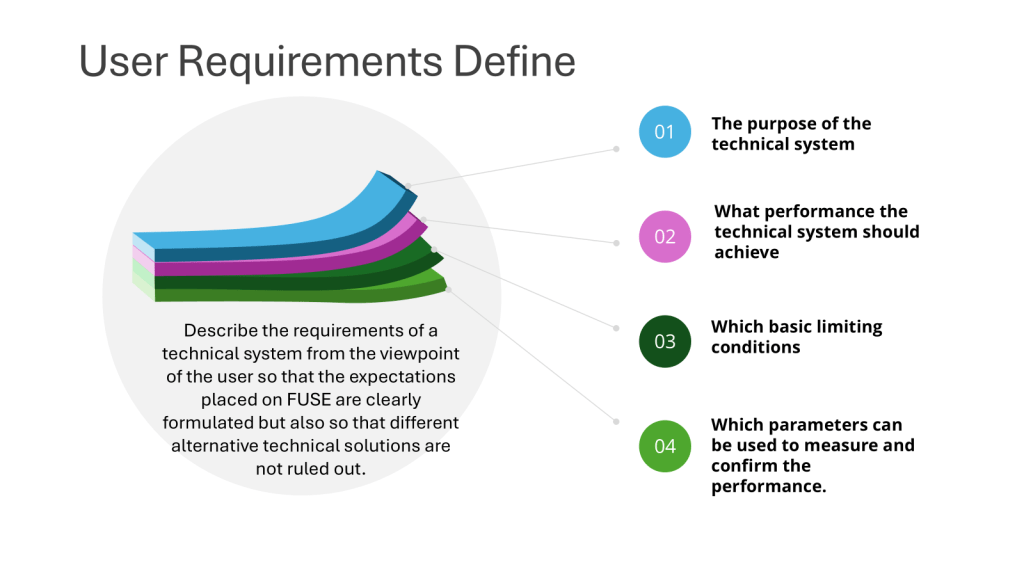

User requirements specifications serve as the foundational document identifying what a system must do to meet specific business needs, product requirements, and operational constraints. They translate high-level business objectives into measurable, testable, and verifiable system behaviors. User requirements focus on what the system must accomplish, not how the organization manages its regulatory obligations.

Consider the fundamental difference between these approaches:

Problematic High-Level Requirement: “The system shall comply with 21 CFR Part 11 validation requirements.”

Proper Detailed Requirements:

- “The system shall generate time-stamped audit trails for all data modifications, including user ID, date/time, old value, new value, and reason for change”

- “The system shall enforce unique user identification through username/password combinations with minimum 8-character complexity requirements”

- “The system shall prevent deletion of electronic records while maintaining complete audit trail visibility”

- “The system shall provide electronic signature functionality that captures the printed name, date/time, and meaning of the signature”

The problematic version tells us nothing about what the system actually needs to do. The detailed versions provide clear, testable criteria that directly support Part 11 compliance while specifying actual system functionality.

Process vs. System: Understanding the Fundamental Categories

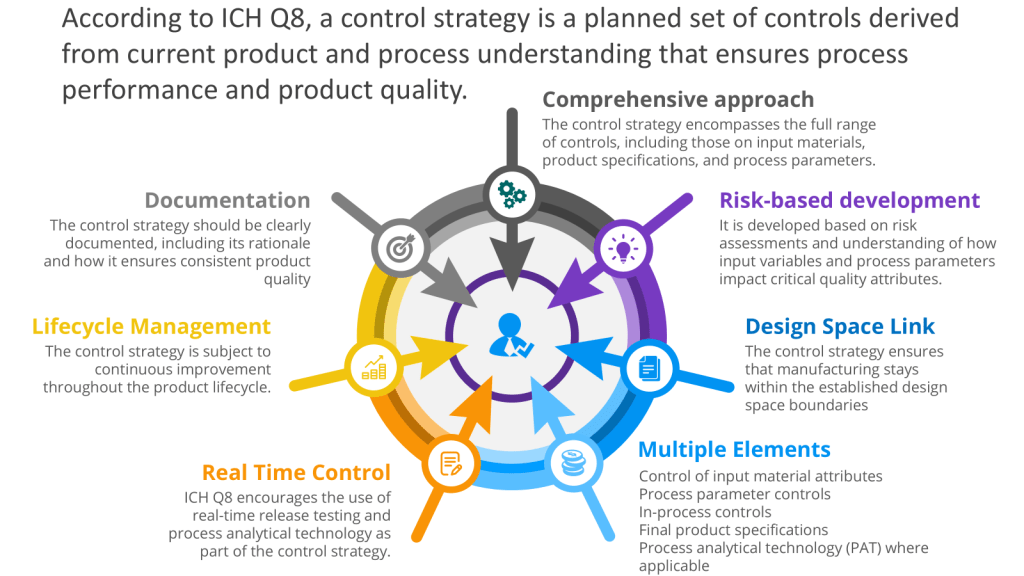

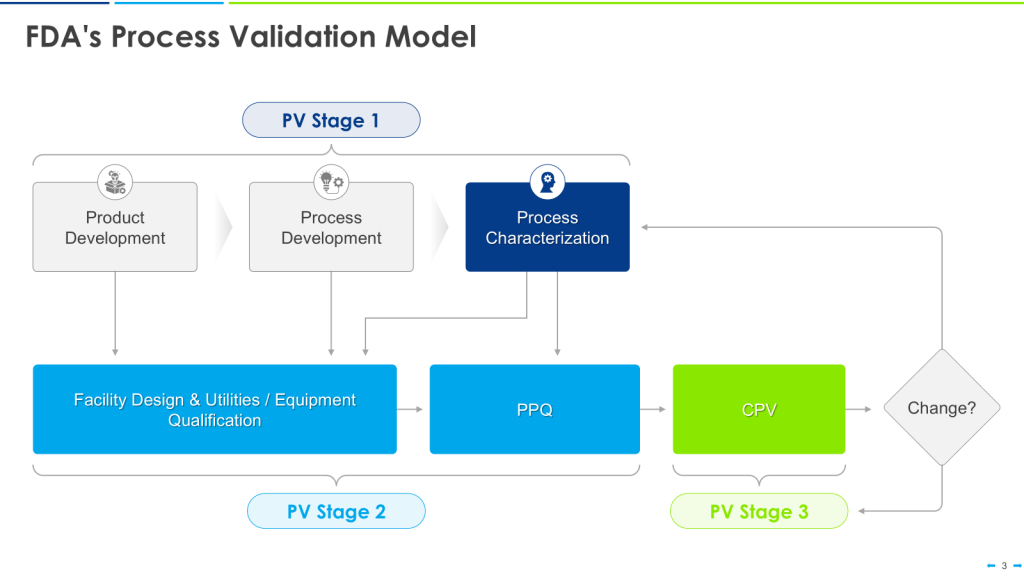

Lifecycle management, risk assessment, and validation represent organizational processes that exist independently of any specific system implementation. These processes define how an organization approaches system development, operation, and maintenance—they are not attributes that can be “built into” software.

Lifecycle processes encompass the entire journey from initial system conception through retirement, including stages such as requirements definition, design, development, testing, deployment, operation, and eventual decommissioning. A lifecycle approach ensures systematic progression through these stages with appropriate documentation, review points, and decision criteria. However, lifecycle management cannot be embedded as a system requirement because it describes the framework within which system development occurs, not system functionality itself.

Risk management processes involve systematic identification, assessment, and mitigation of potential hazards throughout system development and operation. Risk management influences system design decisions and validation approaches, but risk management itself is not a system capability—it is an organizational methodology for making informed decisions about system requirements and controls.

Validation processes establish documented evidence that systems consistently perform as intended and meet all specified requirements. Validation involves planning, execution, and documentation of testing activities, but validation is something done to systems, not something systems possess as an inherent characteristic.

The Illusion of Compliance Through Citation

When user requirements specifications contain broad regulatory citations rather than specific functional requirements, they create several critical problems that undermine effective validation:

- Untestable Requirements: How does one verify that a system “complies with Part 11”? Such requirements provide no measurable criteria, no specific behaviors to test, and no clear success/failure conditions. Verification becomes a subjective exercise in regulatory interpretation rather than objective measurement of system performance.

- Validation Theater: Broad compliance statements encourage checkbox validation exercises where teams demonstrate regulatory awareness without proving functional capability. These validations often consist of mapping system features to regulatory sections rather than demonstrating that specific user needs are met.

- Scope Ambiguity: Part 11 and Annex 11 contain numerous requirements, many of which may not apply to specific systems or use cases. Blanket compliance statements fail to identify which specific regulatory requirements are relevant and which system functions address those requirements.

- Change Management Nightmares: When requirements reference entire regulatory frameworks rather than specific system behaviors, any regulatory update potentially impacts system validation status. This creates unnecessary re-validation burdens and regulatory uncertainty.

Building Requirements That Actually Work

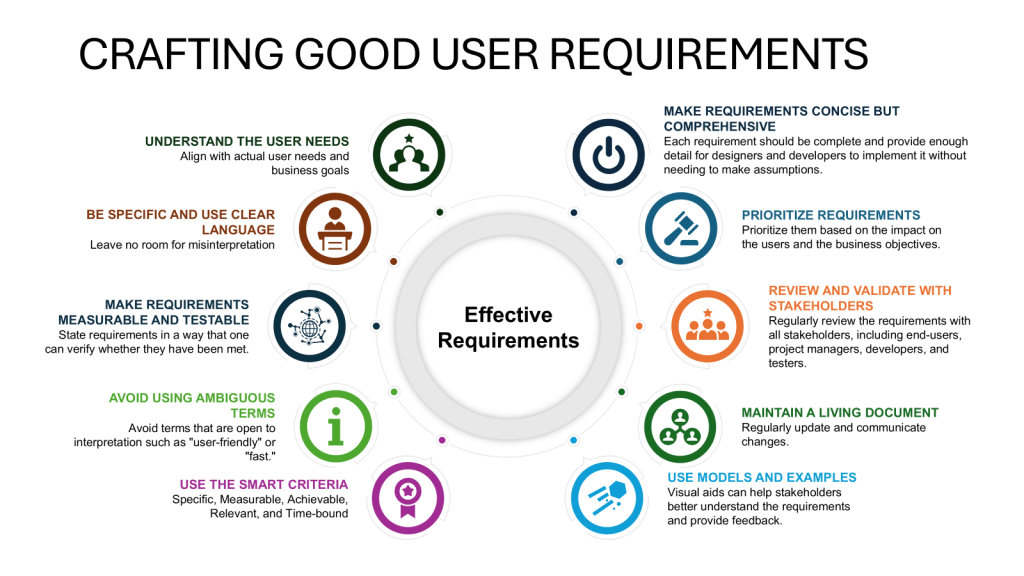

Effective user requirements specifications address regulatory compliance through detailed, system-specific functional requirements that directly support regulatory objectives. This approach ensures that validation activities test actual system capabilities rather than regulatory awareness

Focus on Critical Quality Attributes: Rather than citing broad compliance frameworks, identify the specific product and process attributes that regulatory requirements are designed to protect. For pharmaceutical systems, this might include data integrity, product traceability, batch genealogy, or contamination prevention.

Translate Regulatory Intent into System Functions: Understand what each applicable regulation is trying to achieve, then specify system behaviors that accomplish those objectives. Part 11’s audit trail requirements, for example, aim to ensure data integrity and accountability—translate this into specific system capabilities for logging, storing, and retrieving change records.

Maintain Regulatory Traceability: Document the relationship between specific system requirements and regulatory drivers, but do so through traceability matrices or design rationale documents rather than within the requirements themselves. This maintains clear regulatory justification while keeping requirements focused on system functionality.

Enable Risk-Based Validation: Detailed functional requirements support risk-based validation approaches by clearly identifying which system functions are critical to product quality, patient safety, or data integrity. This enables validation resources to focus on genuinely important capabilities rather than comprehensive regulatory coverage.

The Process-System Interface: Getting It Right

The relationship between organizational processes and system requirements should be managed through careful analysis and translation, not through broad regulatory citations. Effective user requirements development involves several critical steps:

Process Analysis: Begin by understanding the organizational processes that the system must support. This includes manufacturing processes, quality control workflows, regulatory reporting requirements, and compliance verification activities. However, the focus should be on what the system must enable, not how the organization manages compliance.

Regulatory Gap Analysis: Identify specific regulatory requirements that apply to the intended system use. Analyze these requirements to understand their functional implications for system design, but avoid copying regulatory language directly into system requirements.

Functional Translation: Convert regulatory requirements into specific, measurable system behaviors. This translation process requires deep understanding of both regulatory intent and system capabilities, but produces requirements that can be objectively verified.

Organizational Boundary Management: Clearly distinguish between requirements for system functionality and requirements for organizational processes. System requirements should focus exclusively on what the technology must accomplish, while process requirements address how the organization will use, maintain, and govern that technology.

Real-World Consequences of the Current Approach

The practice of embedding high-level regulatory requirements in user requirements specifications has created systemic problems throughout the pharmaceutical industry:

- Validation Inefficiency: Teams spend enormous resources demonstrating broad regulatory compliance rather than proving that systems meet specific user needs. This misallocation of validation effort undermines both regulatory compliance and system effectiveness.

- Inspection Vulnerability: When regulatory inspectors evaluate systems against broad compliance claims, they often identify gaps between high-level assertions and specific system capabilities. Detailed functional requirements provide much stronger inspection support by demonstrating specific regulatory compliance mechanisms.

- System Modification Complexity: Changes to systems with broad regulatory requirements often trigger extensive re-validation activities, even when the changes don’t impact regulatory compliance. Specific functional requirements enable more targeted change impact assessments.

- Cross-Functional Confusion: Development teams, validation engineers, and quality professionals often interpret broad regulatory requirements differently, leading to inconsistent implementation and validation approaches. Detailed functional requirements provide common understanding and clear success criteria.

A Path Forward: Detailed Requirements for Regulatory Success

The solution requires fundamental changes in how the pharmaceutical industry approaches user requirements development and regulatory compliance documentation:

Separate Compliance Strategy from System Requirements: Develop comprehensive regulatory compliance strategies that identify applicable requirements and define organizational approaches for meeting them, but keep these strategies distinct from system functional requirements. Use the compliance strategy to inform requirements development, not replace it.

Invest in Requirements Translation: Build organizational capability for translating regulatory requirements into specific, testable system functions. This requires regulatory expertise, system knowledge, and requirements engineering skills working together.

Implement Traceability Without Embedding: Maintain clear traceability between system requirements and regulatory drivers through external documentation rather than embedded citations. This preserves regulatory justification while keeping requirements focused on system functionality.

Focus Validation on Function: Design validation approaches that test system capabilities directly rather than compliance assertions. This produces stronger regulatory evidence while ensuring system effectiveness.

Lifecycle, risk management, and validation are organizational processes that guide how we develop and maintain systems—they are not system requirements themselves. When we treat them as such, we undermine both regulatory compliance and system effectiveness. The time has come to abandon this regulatory red herring and embrace requirements practices worthy of the products and patients we serve.