The FDA’s recent warning letter to BEO Pharmaceuticals highlights significant compliance failures that serve as crucial lessons for pharmaceutical manufacturers. The inspection conducted in late 2024 revealed multiple violations of Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations, spanning from inadequate component testing to serious process validation deficiencies. This analysis examines the key issues identified, contextualizes them within regulatory frameworks, and extracts valuable insights for pharmaceutical quality professionals.

Component Testing and Supplier Qualification Failures

BEO Pharmaceuticals failed to adequately test incoming raw materials used in their over-the-counter (OTC) liquid drug products, violating the fundamental requirements outlined in 21 CFR 211.84(d)(1) and 211.84(d)(2). These regulations mandate testing each component for identity and conformity with written specifications, plus validating supplier test analyses at appropriate intervals.

Most concerning was BEO’s failure to test high-risk components for diethylene glycol (DEG) and ethylene glycol (EG) contamination. The FDA emphasized that components like glycerin require specific identity testing that includes limit tests for these potentially lethal contaminants. The applicable United States Pharmacopeia-National Formulary (USP-NF) monographs establish a safety limit of not more than 0.10% for DEG and EG. Historical context makes this violation particularly serious, as DEG contamination has been responsible for numerous fatal poisoning incidents worldwide.

While BEO eventually tested retained samples after FDA discussions and found no contamination, this reactive approach fundamentally undermines the preventive philosophy of CGMP. The regulations are clear: manufacturers must test each shipment of each lot of high-risk components before incorporating them into drug products9.

Regulatory Perspective on Component Testing

According to 21 CFR 211.84, pharmaceutical manufacturers must establish the reliability of their suppliers’ analyses through validation at appropriate intervals if they intend to rely on certificates of analysis (COAs). BEO’s failure to implement this requirement demonstrates a concerning gap in their supplier qualification program that potentially compromised product safety.

Quality Unit Authority and Product Release Violations

Premature Product Release Without Complete Testing

The warning letter cites BEO’s quality unit for approving the release of a batch before receiving complete microbiological test results-a clear violation of 21 CFR 211.165(a). BEO shipped product on January 8, 2024, though microbial testing results weren’t received until January 10, 2024.

BEO attempted to justify this practice by referring to “Under Quarantine” shipping agreements with customers, who purportedly agreed to hold products until receiving final COAs. The FDA unequivocally rejected this practice, stating: “It is not permissible to ship finished drug products ‘Under Quarantine’ status. Full release testing, including microbial testing, must be performed before drug product release and distribution”.

This violation reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of quarantine principles. A proper quarantine procedure is designed to isolate potentially non-conforming products within the manufacturer’s control-not to transfer partially tested products to customers. The purpose of quarantine is to ensure products with abnormalities are not processed or delivered until their disposition is clear, which requires complete evaluation before leaving the manufacturer’s control.

Missing Reserve Samples

BEO also failed to maintain reserve samples of incoming raw materials, including APIs and high-risk components, as required by their own written procedures. This oversight eliminates a critical safeguard that would enable investigation of material-related issues should quality concerns arise later in the product lifecycle.

Process Validation Deficiencies

Inadequate Process Validation Approach

Perhaps the most extensive violations identified in the warning letter related to BEO’s failure to properly validate their manufacturing processes. Process validation is defined as “the collection and evaluation of data, from the process design stage through commercial production, which establishes scientific evidence that a process is capable of consistently delivering quality product”.

The FDA identified several critical deficiencies in BEO’s approach to process validation:

- BEO shipped products as early as May 2023, but only prepared and approved validation reports in October 2024-a clear indication that validation was retroactively conducted rather than implemented prior to commercial distribution.

- Process validation reports lacked essential details such as comprehensive equipment lists, appropriate critical process parameters, adequate sampling instructions, and clear acceptance criteria.

- Several validation reports relied on outdated data from 2011-2015 from manufacturing operations at a different facility under a previous business entity.

These findings directly contradict the FDA’s established process validation guidance, which outlines a systematic, three-stage approach:

- Process Design: Defining the commercial manufacturing process based on development and scale-up activities.

- Process Qualification: Evaluating process capability for reproducible commercial manufacturing.

- Continued Process Verification: Ongoing assurance during routine production that the process remains controlled.

The FDA guidance emphasizes that “before any batch from the process is commercially distributed for use by consumers, a manufacturer should have gained a high degree of assurance in the performance of the manufacturing process”. BEO’s retroactive approach to validation fundamentally violated this principle.

Pharmaceutical Water System Failures

A particularly concerning finding was BEO’s failure to establish that their purified water system was “adequately designed, controlled, maintained, and monitored to ensure it is consistently producing water that meets the USP monograph for purified water and appropriate microbial limits”. This water was used both as a component in liquid drug products and for cleaning manufacturing equipment and utensils.

Water for pharmaceutical use must meet strict quality standards depending on its intended application. Purified water systems used in non-sterile product manufacturing must meet FDA’s established action limit of not more than 100 CFU/mL. The European Medicines Agency similarly emphasizes that the control of the quality of water throughout the production, storage and distribution processes, including microbiological and chemical quality, is a major concern.

BEO’s current schedule for water system maintenance and microbiological testing was deemed “insufficient”-a critical deficiency considering water’s role as both a product component and cleaning agent. This finding underscores the importance of comprehensive water system validation and monitoring programs as fundamental elements of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Laboratory Controls and Test Method Validation

BEO failed to demonstrate that their microbiological test methods were suitable for their intended purpose, violating 21 CFR 211.160(b). Specifically, BEO couldn’t provide evidence that their contract laboratory’s methods could effectively detect objectionable microorganisms in their specific drug product formulations.

The FDA noted that while BEO eventually provided system suitability documentation, “the system suitability protocols for the methods specified in USP <60> and USP <62> lacked the final step to confirm the identity of the recovered microorganisms in the tests”. This detail critically undermines the reliability of their microbiological testing program, as method validation must demonstrate that the specific test can detect relevant microorganisms in each product matrix.

Strategic Implications for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers

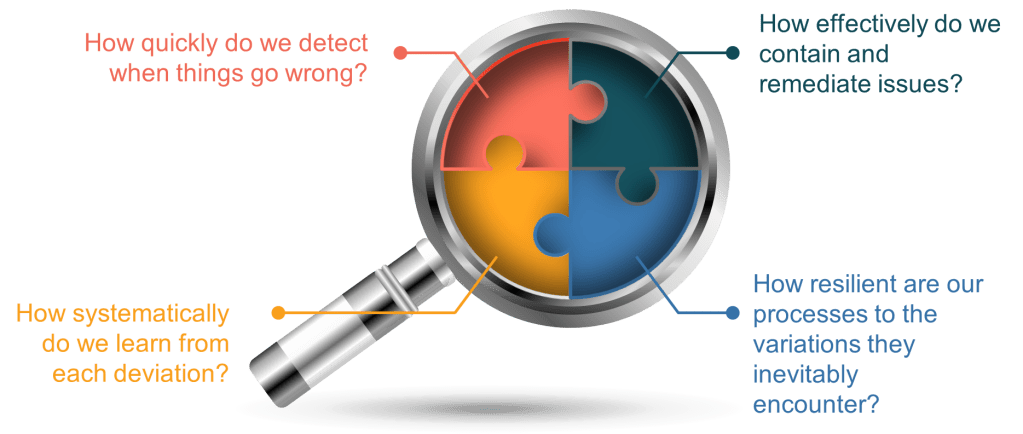

The BEO warning letter illustrates several persistent challenges in pharmaceutical CGMP compliance:

- Component risk assessment requires special attention for high-risk ingredients with known historical safety concerns. The DEG/EG testing requirements for glycerin and similar components represent non-negotiable safeguards based on tragic historical incidents.

- Process validation must be prospective, not retroactive. The industry standard clearly establishes that validation provides assurance before commercial distribution, not after.

- Water system qualification is fundamental to product quality. Pharmaceutical grade water systems require comprehensive validation, regular monitoring, and appropriate maintenance schedules to ensure consistent quality.

- Quality unit authority must be respected. The quality unit’s independence and decision-making authority cannot be compromised by commercial pressures or incomplete testing.

- Testing methods must be fully validated for each specific application. This is especially critical for microbiological methods where product-specific matrix effects can impact detectability of contaminants.