As someone deeply embedded in the quality and regulatory systems that define our industry’s backbone, I’ve been a part of almost a dozen organizational upheavals in my 30 years, and witnessed from afar countless others. Some companies emerge stronger, their teams galvanized by new possibilities. Others fragment, losing critical talent and institutional knowledge just when they need it most. The difference invariably comes down to how leadership approaches the most human aspect of change: the emotional journey that every team member must navigate.

The Emotional Reality of Change

Let’s address what many executives prefer to sidestep: change is grief. When your familiar processes disappear, when trusted colleagues move to different roles, when the very systems you’ve mastered become obsolete—these losses are real and profound.The process of organizational grief follows a pattern similar to J. William Worden’s Four Tasks of Mourning: accepting the reality of what has been lost, processing the emotional pain of transition, adjusting to the new organizational reality, and finding ways to maintain connection to valuable aspects of the past while embracing the future.

In pharmaceutical M&As, this emotional cycle plays out with particular intensity. A quality manager who spent years perfecting validation protocols suddenly faces entirely new systems. A regulatory affairs specialist discovers their hard-won agency relationships may become irrelevant in a restructured organization. A manufacturing technician watches as decades of process knowledge gets labeled “legacy” and marked for replacement.

The instinct among well-meaning leaders is often to minimize these concerns or rush past them toward “more productive” discussions about synergies and efficiencies. This is a critical mistake. Research consistently shows that ignoring the emotional dimensions of change leads to higher resistance, decreased productivity, and catastrophic talent loss. In our industry, where specialized knowledge takes years to develop and regulatory missteps can cost millions, we cannot afford such oversight.

The Merger Reality Check

The numbers tell a sobering story. McKinsey research indicates that 47% of employees leave within the first year following a merger, with turnover reaching 75% within three years. In pharmaceutical companies, where regulatory expertise and process knowledge are irreplaceable assets, such exodus represents value destruction that far exceeds any projected synergies.

But these statistics reflect a choice, not an inevitability. Companies that approach M&A with genuine people-first principles achieve dramatically different outcomes. They recognize that every employee carries not just technical skills, but institutional memory, client relationships, and innovation potential that cannot be easily replaced.

Consider the emotional journey that unfolds in any significant merger. Initial excitement about growth opportunities quickly gives way to anxiety about job security. Questions multiply faster than answers: Will my role survive? Who will my new manager be? How will our proven quality systems integrate with theirs? The uncertainty creates what researchers call “change fatigue”—a state where even high-performing employees become disengaged and start planning their exit.

The Leadership Response: Compassion Meets Strategy

Effective leaders during transformation periods understand that acknowledging grief isn’t a sign of weakness—it’s a prerequisite for moving forward. Just as we would never expect someone who has lost a loved one to immediately return to peak performance, we cannot expect employees experiencing organizational loss to seamlessly adapt without support and time.

This doesn’t mean wallowing in nostalgia or avoiding necessary changes. Instead, it means creating space for honest dialogue about what’s being lost, what’s being gained, and how we’ll navigate the journey together. In practical terms, this involves several key strategies:

Transparent Communication as Foundation

Regular town halls, one-on-one conversations, and written updates that acknowledge both opportunities and challenges. Successful change requires consistent messaging about how the change will enhance rather than replace existing capabilities.

Structured Listening Programs

Creating formal mechanisms for employees to voice concerns, ask questions, and propose solutions. The best leaders understand that frontline employees often have the clearest view of integration challenges and opportunities.

Milestone Recognition

Celebrating both old achievements and new progress. This helps bridge the psychological gap between what was valuable before and what will be valuable going forward.

People Development as Transformation Strategy

Here’s where the opportunity truly lies: periods of organizational change, however challenging, represent unparalleled opportunities for individual growth and development. When done thoughtfully, transformation initiatives can accelerate employee capabilities in ways that benefit both individuals and organizations for years to come.

The most successful pharmaceutical companies approach M&A not as a cost-cutting exercise, but as a talent multiplication opportunity. They recognize that bringing together diverse teams with different expertise creates potential for innovation that neither organization could achieve alone.

Expanded Learning Opportunities

Mergers naturally create needs for new skills—from understanding different regulatory frameworks to mastering unfamiliar technologies. Forward-thinking companies invest heavily in training programs that help employees not just adapt, but excel in the expanded environment.

Cross-Functional Exposure

Integration projects provide unique opportunities for employees to work outside their usual domains. A quality assurance specialist might contribute to IT system selection. A regulatory affairs manager might help design new manufacturing processes. These experiences broaden skill sets and create more versatile, valuable team members.

Leadership Development Acceleration

Transformation periods naturally identify emerging leaders—those who step up during uncertainty, build bridges between different teams, and help others navigate change. Smart companies fast-track development programs for these individuals, recognizing that they represent the leadership pipeline for the integrated organization.

Innovation Through Integration

When teams from different companies combine their approaches, the result is often superior to either original method. This collaborative innovation process not only solves immediate integration challenges but builds creative problem-solving capabilities that benefit future projects.

The Regulatory Dimension

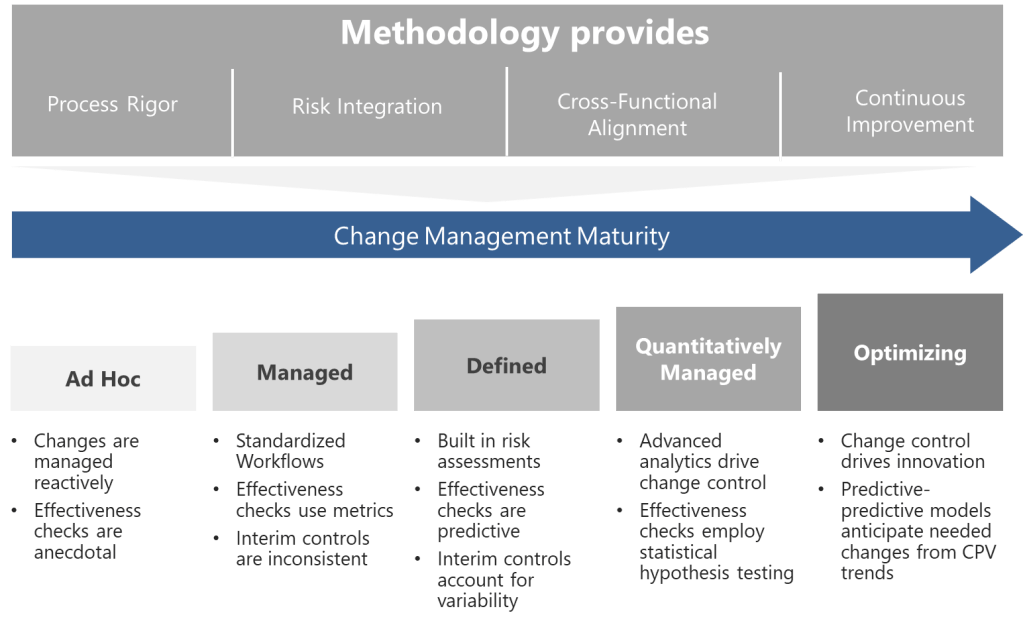

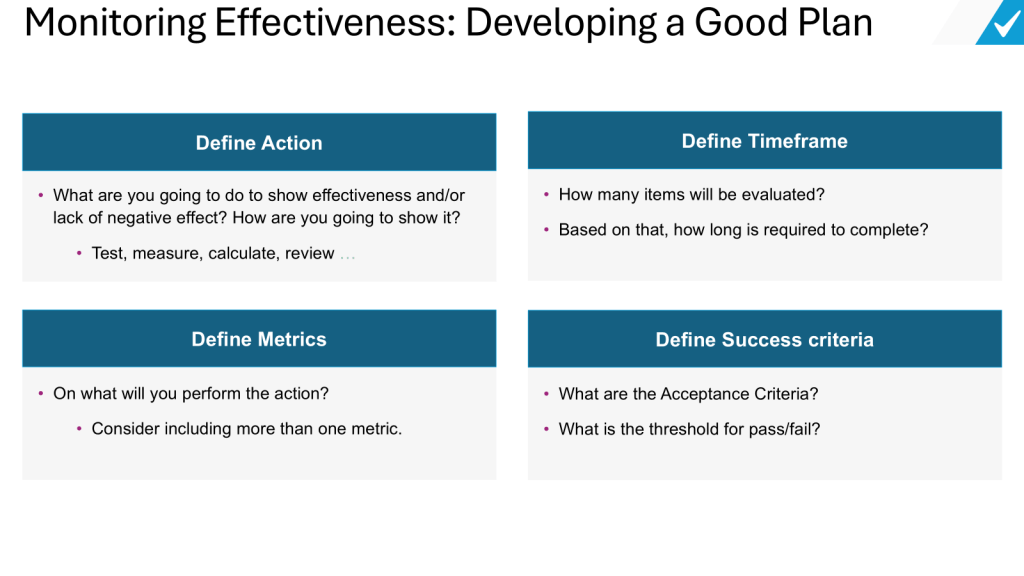

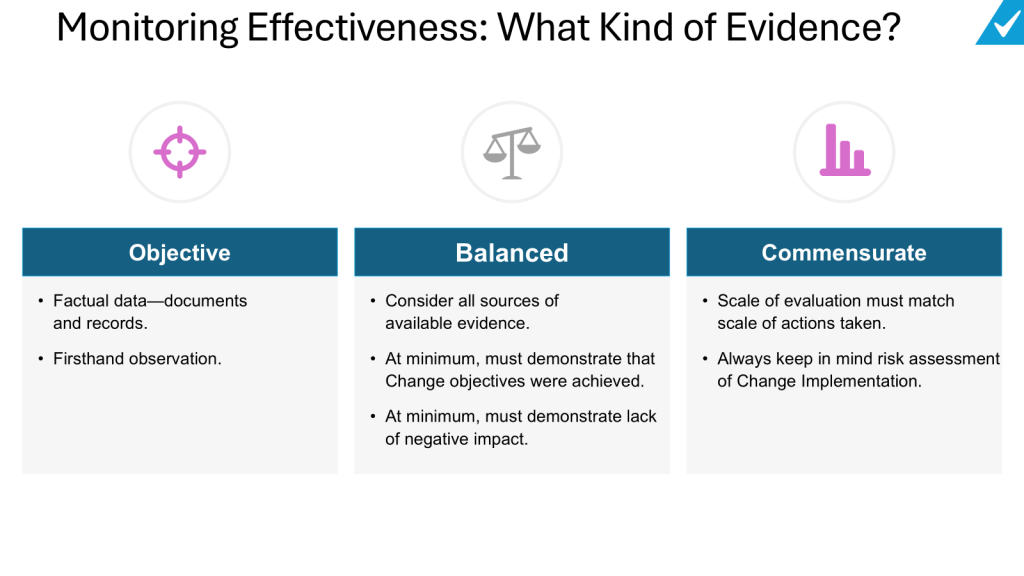

In our industry, change management takes on additional complexity due to regulatory requirements. Every process modification, system integration, or organizational restructure must comply with stringent guidelines from FDA, EMA, and other global agencies. This creates both challenges and opportunities for employee development.

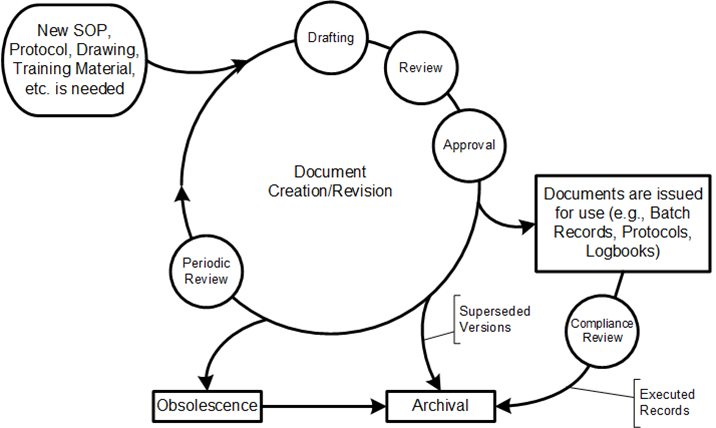

The challenge is that regulatory compliance cannot be compromised during transition periods. Quality systems must remain validated, audit trails must stay intact, and critical processes cannot experience disruption. This constraint can make change feel slower and more bureaucratic than in other industries.

The opportunity, however, is significant. Employees who master change management within regulatory frameworks develop highly transferable skills. They learn to think systematically about risk, document decisions thoroughly, and maintain compliance while driving innovation. These capabilities are increasingly valuable as the industry embraces digital transformation and advanced manufacturing technologies.

Supporting Your People: Practical Strategies

Leading people through pharmaceutical industry changes requires specific, actionable approaches:

Create Psychological Safety

Team members must feel safe to express concerns, admit knowledge gaps, and ask for help without fear of job loss or career damage. This is particularly crucial in our industry where admitting uncertainty about regulatory requirements or quality procedures can feel risky.

Provide Multiple Development Pathways

Different employees will respond to change differently. Some thrive on new challenges, others prefer stability. Successful integration programs offer various ways for people to contribute and grow.

Maintain Connection to Purpose

Help employees understand how their individual roles contribute to the larger mission of improving patient outcomes. This connection provides stability during periods of organizational flux.

Invest in Skill-Building

Use integration challenges as opportunities to build capabilities that will serve employees throughout their careers. This might include project management skills, cross-cultural communication, or advanced technical training.

Recognize and Reward Adaptation

Publicly acknowledge employees who embrace change, help others through transitions, or find innovative solutions to integration challenges. This reinforces the behaviors you want to see more of.

The Long View: Building Resilient Organizations

The pharmaceutical companies that will thrive in the coming decade aren’t just those with the strongest pipelines or the largest market caps—they’re the ones with the most adaptable, engaged, and continuously developing workforce. In an industry where change is accelerating due to technological advancement, regulatory evolution, and competitive pressure, organizational resilience depends entirely on people resilience.

This means shifting from viewing change as a necessary evil to embracing it as a competitive advantage. Companies that become excellent at helping their people navigate transitions don’t just survive disruption—they seek it out as a source of growth and innovation.

The most successful pharmaceutical leaders I’ve observed share a common trait: they understand that every change initiative is fundamentally a people development initiative. They ask not just “How do we integrate these systems?” but “How do we help our people become more capable through this integration?” They measure success not just in synergies captured but in employees retained, skills developed, and innovation unlocked.

Moving Forward Together

Change in the pharmaceutical industry isn’t slowing down. If anything, the pace is accelerating as companies race to develop next-generation therapies, implement AI-driven processes, and adapt to evolving regulatory landscapes. The question isn’t whether your organization will face significant transitions—it’s whether you’ll use those transitions to strengthen your most valuable asset: your people.

The path forward requires courage to acknowledge the emotional reality of change, wisdom to invest in people development during difficult periods, and persistence to maintain focus on long-term capability building even when short-term pressures are intense. It means accepting that some sadness about what’s changing is not only normal but necessary—and that supporting people through that sadness is not just compassionate leadership, but strategic necessity.

As we navigate this era of transformation, let’s remember that behind every quality system, every regulatory filing, and every breakthrough therapy are real people with real concerns, real aspirations, and real potential. Our success in managing change will be measured not just by the deals we complete or the synergies we capture, but by the careers we launch, the capabilities we build, and the culture of continuous growth we create.

The future belongs to organizations that can transform while honoring their people, innovate while maintaining their values, and grow while nurturing the human connections that make all achievement possible. In an industry dedicated to healing, surely we can extend that same spirit of care to the transformation of our own organizations.