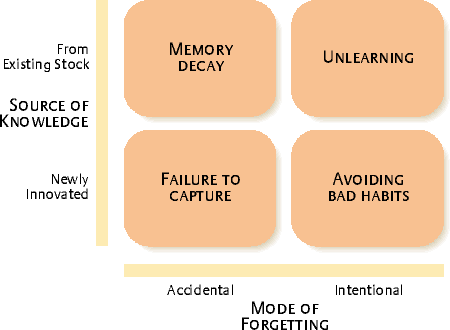

DeHolan and Phillips introduced the concept of organizational forgetting to our concepts of knowledge management. While unintentional forgetting is something we usually want to avoid, there is a time when we want to intentionally forget. Perhaps after a corporate merger we are combining systems or replacing systems. Perhaps it is the result of a large step forward in technology, or an out-right replacement. Some major cultural transformation comes along. And the last thing we want is for no-one to be able to forget the old. For those concepts to linger in our memory and our decisions. For that is a risk that can easily lead to deviations.

Take for example changes in document numbering. Fairly simple of the surface but remember that procedure number is the tag which we use in conversation. No-one ever gives the whole title; we throw around these tags left and right and for our own coded language (another topic worthy of a blog post). Then we change our numbering format and a year later everyone still uses the old number. And mistakes start creeping up. Or just the perception of mistakes builds. Or perhaps everyone still thinks in the manner of the old ERP’s logic, and forget to do crucial aspects of master data management when a change is made. You get the idea

This purposeful frogetting, an aspect of knowledge management (and change management) – that of the purposeful removal of knowledge — is a critical step in our systematic approach and an important part of our strategic toolkit. However, it is very difficult, as deeply embedded pieces of organizational knowledge are generally locked in place by various other pieces of organizational knowledge that depend on them, and removing one implies modifying the others as well. We need to develop the tools to dismantle the previous way of doing work — the unneeded routines and formerly dominant logics of our changed systems.

One of the best way to do this is to get rid of cues. All the little breadcrumbs left behind. If you want people to stop using old document numbers, ensure that no document folks would use on their daily basis has those numbers. However, this ideal model of radical elimination of all cues associated with the old routine seems rather unlikely in all changes from old to new . So when we are working on our change its important to select those cues that will have the biggest bang for our buck. Some general ideas to help inform this are:

- Look for opportunities to drive out mix-messages – aim for consistency in message

- Ensure there are positive reinforcements for use of the new routine

- Actively constrain the to-be-forgotten activity. Reduce the time in two different processes. Do a radical transformation. Reduce the confusion.

- Reward the individual for participating in the new way. The group can’t change faster than the sum of the individuals, so incentive the change.

When doing a change it is important to consider these as risks, and build into your change plan. Incorporate into your training. For the basis of your communications. Drive out the old, embrace the new. Otherwise you are just increasing the risks inherent in your new way of working. But like many aspects of change management, easy in concept, difficult in execution.