I am here at the Veeva R&D Summit this year. As always I’m looking forward to nerd prom, I mean the trade show where half the people I know show up.

In this post I’m going to keep a running tally of what stood out to me on day 1, and maybe draw some themes out.

Networking Breakfasts

First, I hate getting up in time to make it to a breakfast. But these are my favorite events, organized networking. No agendas, no slides, no presentations. Just a bunch of fellow professionals who care about a specific topic and are more than happy to share.

Today I went to the Validation Vault breakfast, which means a lot of fellow validation mind folks. What did the folks at my table talk about:

- The draft Annex 11, especially with security being the next new thing

- Risk assessments leading to testing activities

- Building requirements from templates and from risk based approaches

- The danger of the Vault Owner

- Everyone’s strggles getting people to execute value-added UATs

- CSA as a comedy show

Opening Keynote

TAt the keynote, Veeva wanted to stress the company’s strategic direction, highlighting three major themes that will shape the life sciences industry: a strong focus on artificial intelligence through VeevaAI, the push toward industry standard applications, and an overarching emphasis on simplification and standardization.

VeevaAI and the Rise of Intelligent Agents

Veeva certainly hoped that there would be a lot of excitement around their most significant announcement centered on their comprehensive AI initiative, VeevaAI, which represents a shift toward agentic artificial intelligence across their entire platform ecosystem. Veeva wants you to know very explictely that this isn’t merely adding AI features as an afterthought—it’s about building intelligent agents directly into the Vault Platform with secure, direct access to data, documents, and workflows.

Those of us who have implemented a few Vaults know that the concept of AI agents isn’t entirely new to Veeva’s ecosystem. These intelligent assistants have been operating in specific areas like Safety and electronic Trial Master File (eTMF) systems for years. However, the company is now wants to expand this concept, planning to implement custom-built agents across all Veeva applications

They also really want the investors to know they are doing that sexy new thing, AI. Curious as a Public Benefit Corporation that they didn’t talk about their environmental commitements and the known impacts of AI upon the environment.

The Technical Foundation: Model Context Protocol

Veeva is working to implement Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP) in 2026. MCP represents an open standard that functions like “USB-C for AI applications,” enabling standardized connections between AI models and various data sources and tools. This protocol allows AI agents to communicate seamlessly with each other and access real-time data from distributed environments.

This protocol has gained significant traction across the technology industry. Major companies like Google, OpenAI, and Microsoft have embraced MCP, demonstrating its viability as a foundation for enterprise AI strategies. So this adoption makes sense.

Rollout Timeline and Early Adopter Program

Veeva’s AI implementation follows a structured timeline. The early adopter program launches in 2026, with general availability expected by 2028. This phased approach allows the company to work closely with select customers as a focus group, sharing best practices while developing the pricing model. Different Vault applications will receive AI capabilities across quarters—for example, Quality applications are scheduled for April 2026.

The first release of VeevaAI is planned for December 2025 and will include both AI Agents and AI Shortcuts. AI Agents provide application-specific automation with industry-specific prompts and safeguards, while AI Shortcuts enable user-defined automations for repetitive tasks.

Industry Standard Applications: Building Market Presence

The second major theme from the Summit focused on Industry Standard Applications, which represents an evolution of Veeva’s previous Vault Essentials and Vault Basics initiatives. This strategy aims to solidify Veeva’s market presence by providing standardized, pre-configured applications that organizations can implement quickly and efficiently.

Focus on eTMF and QualityDocs

Veeva is initially concentrating on two key areas: eTMF (electronic Trial Master File) and QualityDocs.

Beyond AI and standardization, Veeva announced a few potentially significant platform improvements coming in 2025.

Action Triggers

A quick search on Veeva’s web pages tells me that Action Triggers represent a major advancement in Vault Platform functionality, allowing administrators to write simple conditional logic that executes when CREATE, UPDATE, or DELETE operations occur on records. This feature enables Vault to perform actions that previously required complex Java SDK Record Triggers, such as sending notifications when fields are updated, updating related records, starting workflows, or preventing record saves under specific conditions.

The implementation uses IF-THEN-ELSE statements with a context-sensitive editor, making it accessible to administrators without extensive programming knowledge. Recent enhancements include support for the IsChanged() function, which improves efficiency by evaluating whether fields have been modified.

I’ve got uses in mind for this. Pretty important as we start thinking of agentic functionality.

Document View Enhancement

I think I will better understand what is coming here later in the Summit.

Process Monitor

The functionality likely provides enhanced visibility and control over business processes across Vault applications. Hopefully we will learn more, probably at the Quality keynote.

Regulatory Vault: Global Label Authoring and Management

Looking ahead to early 2027, Veeva plans to roll out global label authoring and management capabilities within Regulatory Vault. This enhancement will provide comprehensive tracking and management of labeling concept updates and deviations across global and local levels. Organizations will be able to enter proposed changes, send them to affiliate teams for local disposition, and capture deviations in local labeling while maintaining global visibility throughout the approval and submission process.

Quality Keynote

One of the nice things about being at a CDMO is I’ve pretty much shed all my need to pay attention to the other Vaults, so this will be the first summit in a long time I focus exclusively on Quality Vault.

Veeva really wants us to know they are working hard to streamline user experience enhancements. This makes sense, because boy do people like to complain.

Veeva discussed three key improvements designed to simplify daily operations:

- Streamlined Document Viewer was poorly defined. I’ll need to see this before weighing in.

- Action Home Page introduces task-based navigation with faster access to critical content. This redesign recognizes that users need rapid access to their most important tasks and documents, reducing the time spent navigating through complex menu structures.

- Process Navigator brings dynamic association of content, effectively automating parts of the buildout. The ability to dynamically link relevant content to specific process steps could significantly reduce process deviations and improve consistency. Process navigator is my favorite underused part of Quality Vault, so I am thrilled to see it get some love.

Continuing the theme of Agentic AI, Quality Event Suggestions focuses on aggregating data to enable suggestions for possible texts. I hope this is better than word suggestions in a text app. Should be fun to qualify.

Change Control is receiving significant love with:

- action paths. This enhancement focuses on grouping and sequencing changes to improve repeatability

- The expanded capability to involve external partners in change control processes. Managing changes that span partners (suppliers, CxO, sponsors, etc), has traditionally been complex and prone to communication gaps. Streamlined external partner integration should reduce approval cycles and improve change implementation quality.

- Increased integration between QMS and RIM (Regulatory Information Management) creates a more unified quality ecosystem. This integration enables seamless flow of regulatory requirements into quality processes, ensuring compliance considerations are embedded throughout operations.

The Audit Room feature addresses both front and back room audit activities, providing a structured way to expose inspection requests to auditors. This capability recognizes that inspections and audits increasingly rely on electronic systems and data presentations. Having a standardized audit interface could significantly reduce inspection preparation time and improve confidence in the quality systems. The ability to present information clearly and comprehensively during audits and inspections directly impacts inspection outcomes and business continuity.

The training enhancements demonstrate Veeva’s commitment to modern learning approaches:

- Refresher training receives increased focus, recognizing that maintaining competency requires ongoing reinforcement rather than one-time training events.

- Good to see continued LearnGxP library expansion with over 60 new courses and 115+ course updates ensures that training content remains current with evolving regulations and industry best practices. One of the best learning packages out there for purchase continues to get better.

- Wave-based assignments with curriculum prerequisites introduce more sophisticated training management capabilities. This enhancement allows organizations to create logical learning progressions that ensure foundational knowledge before advancing to complex topics. The approach particularly benefits organizations with high staff turnover or complex training requirements across diverse roles.

Revolutionary LIMS: True Cloud Architecture

Veeva really wants you to know their LIMS is different fro all the other LIMS, stressing they have several key advantages over legacy systems:

- True Cloud Architecture eliminates the infrastructure management burden that traditionally consumes significant IT resources. Unlike legacy LIMS that are merely hosted in the cloud, Veeva LIMS is built cloud-native, providing better performance, scalability, and automatic updates.

- Collapsing System Layers represents a philosophical shift in laboratory informatics. Traditionally, lab execution has been separate from LIMS functionality, creating data silos and integration challenges. Veeva’s approach unifies these capabilities. I am excited about what will come as they extend the concept to environmental monitoring and creating a more cohesive laboratory ecosystem.

AI-Powered Quality Agents: Early Adopter Opportunities

Building on the Keynote it was announced that there will be 8-10 early adopters for Quality Event Agents. These AI-powered agents promise three capabilities:

- Automatic Narrative Summary Generation across quality events could revolutionize how organizations analyze and report on quality trends. Instead of manual compilation of event summaries, AI agents would automatically generate comprehensive narratives that identify patterns, root causes, and improvement opportunities.

- Document Summarization Agents will summarize SOP version changes and other critical document updates. Automated change summaries could improve change communication and training development. The ability to quickly understand what changed between document versions reduces review time and improves change implementation quality.

- Document Translation Agents address the global nature of pharmaceutical operations. For CDMOs working with international sponsors or regulatory authorities, automated translation of quality documents while maintaining technical accuracy could accelerate global project timelines and reduce translation costs.

Lunch Networking – LIMS

Another good opportunity to network. The major concern of the table I sat at was migration.

Validation Manager

After four years of watching Validation Manager evolve since its 2021 announcement, the roadmap presentation delivered a compelling case for production readiness. With over 50 customers now actively using the system, Veeva is clearly positioning Validation Manager as a mature solution ready for widespread adoption across the pharmaceutical industry.

Recent Enhancements: Streamlining the Validation Experience

The latest updates to Validation Manager demonstrate Veeva’s commitment to addressing real-world validation challenges through improved user experience and workflow optimization.

User Experience Improvements

Quick Requirement Creation represents a fundamental shift toward simplifying the traditionally complex process of requirement documentation. This enhancement reduces the administrative burden of creating and managing validation requirements, allowing validation teams to focus on technical content rather than system navigation.

The Requirements Burndown Search Bar provides project managers with rapid visibility into requirement status and progress. For organizations managing multiple validation projects simultaneously, this search capability enables quick identification of bottlenecks and resource allocation issues.

Display Workflow Taskbars for Interfaces addresses a common pain point in collaborative validation environments. The enhanced task visibility during authoring, executing, or approving test scripts and protocols ensures that all stakeholders understand their responsibilities and deadlines, reducing project delays due to communication gaps.

Template Standardization and Execution Features

Template Test Protocols and Test Scripts introduce the standardization capabilities that validation professionals have long requested. These templates enable organizations to maintain consistency across projects while reducing the time required to create new validation documentation.

The Copy Test Script and Protocol Enhancements provide more sophisticated version control and reusability features. For organizations with similar systems or repeated validation activities, these enhancements significantly reduce development time and improve consistency.

Periodic Reviews for Entities automate the ongoing maintenance requirements that regulatory frameworks demand. This feature ensures that validation documentation remains current and compliant throughout the system lifecycle, addressing one of the most challenging aspects of validation maintenance.

Dry Run Capabilities

Dry Run for Test Scripts represents perhaps the most significant quality-of-life improvement in the recent updates. The ability to create clones of test scripts for iterative testing during development addresses a fundamental flaw in traditional validation approaches.

Previously, test script refinement often occurred on paper or through informal processes that weren’t documented. The new dry run capability allows validation teams to document their testing iterations, creating a valuable record of script development and refinement. This documentation can prove invaluable during regulatory inspections when authorities question testing methodologies or script evolution.

Enhanced Collaboration and Documentation

Script and Protocol Execution Review Comments improve the collaborative aspects of validation execution. These features enable better communication between script authors, reviewers, and executors, reducing ambiguity and improving execution quality.

Requirement and Specification Reference Tables provide structured approaches to managing the complex relationships between validation requirements and system specifications. This enhancement addresses the traceability requirements that are fundamental to regulatory compliance.

2025 Developments: Advanced Control and Embedded Intelligence

Flexible Entity Management

Optional Entity Versions address a long-standing limitation in validation management systems. Traditional systems often force version control on entities that don’t naturally have versions, such as instruments or facilities. This enhancement provides advanced control capabilities, allowing organizations to manage activities at both entity and version levels as appropriate.

This flexibility is particularly valuable for equipment qualification and facility validation scenarios where the validation approach may need to vary based on the specific context rather than strict version control requirements.

Intelligent Requirement Scoping

In-Scope Requirements for Activities target specific validation scenarios like change management and regression testing. This capability allows validation teams to define precisely which requirements apply to specific activities, reducing over-testing and improving validation efficiency.

For organizations managing large, complex systems, the ability to scope requirements appropriately can significantly reduce validation timelines while maintaining regulatory compliance and system integrity.

Enhanced Test Script Capabilities

Reference Instruction Prompts represent a much needed evolution from current text-only instruction prompts. The ability to embed images and supporting documents directly into test scripts dramatically improves clarity for script executors.

This enhancement is particularly powerful when testing SOPs as part of User Acceptance Testing (UAT) or other validation activities. The embedded documents can reference other quality documents, creating seamless integration between validation activities and broader quality management systems. This capability could transform how organizations approach process validation and system integration testing. It is a great example of why consolidation in Veeva makes sense.

2026 Vision: Enterprise-Scale Validation Management

The 2026 roadmap reveals Veeva’s ambition to address enterprise-scale validation challenges and complex organizational requirements.

Standardization and Template Management

Activity and Deliverable Templates promise to standardize testing activities across asset classes. This standardization addresses a common challenge in large pharmaceutical organizations where different teams may approach similar validation activities inconsistently.

Validation Team Role Filtering introduces the ability to template various roles in validation projects. This capability recognizes that validation projects often involve complex stakeholder relationships with varying responsibilities and access requirements.

Missing Fundamental Features

Test Step Sequencing is conspicuously absent from current capabilities, which is puzzling given its fundamental importance in validation execution. The 2026 inclusion of this feature suggests recognition of this gap, though it raises questions about why such basic functionality wasn’t prioritized earlier.

User Experience Evolution

The continued focus on test authoring and execution UX improvements indicates that a large portion of 2026 development resources will target user experience refinement. This sustained investment in usability demonstrates Veeva’s commitment to making validation management accessible to practitioners rather than requiring specialized system expertise.

Complex Project Support

Complex Validation Projects support through entity hierarchy and site maps addresses the needs of pharmaceutical organizations with distributed operations. These capabilities enable validation teams to manage projects that span multiple sites, systems, and organizational boundaries.

Collaboration with Suppliers and Vendors tackles the challenge of managing validation packages from external suppliers. This enhancement could significantly reduce the effort required to integrate supplier-provided validation documentation into corporate validation programs. Look forward to Veeva doing this themselves with their own documentation including releases.

AI-Powered Documentation Conversion

Documents to Data Conversion represents the most ambitious enhancement, leveraging platform AI capabilities for easy requirement and specification uploading. This feature promises to automate the conversion of traditional validation documents (URS, FRS, DS, Test Protocols, Test Scripts) into structured data.

This AI-powered conversion could revolutionize how organizations migrate legacy validation documentation into modern systems and how they integrate validation requirements from diverse sources. The potential time savings and accuracy improvements could be transformational for large validation programs.

Specialized Validation Activities

Cleaning and Method Result Calculations address specific validation scenarios that have traditionally required manual calculation and documentation. The cleaning sample location identification and process cross-test execution comparisons demonstrate Veeva’s attention to specialized pharmaceutical validation requirements.

Strategic Assessment: Production Readiness Evaluation

After four years of development and with 50 active customers, Validation Manager appears to have reached genuine production readiness. The roadmap demonstrates:

- Comprehensive Feature Coverage: The system now addresses the full validation lifecycle from requirement creation through execution and maintenance.

- User Experience Focus: Sustained investment in usability improvements suggests the system is evolving beyond basic functionality toward practitioner-friendly operation.

- Enterprise Scalability: The 2026 roadmap addresses complex organizational needs, indicating readiness for large-scale deployment.

- Integration Capabilities: Features like embedded documentation references and supplier collaboration demonstrate understanding of validation as part of broader quality ecosystems.

Batch Management Roadmap

With seven customers now actively using Batch Release Management, Veeva is building momentum in one of the most critical areas of pharmaceutical manufacturing operations. The system’s focus on centralizing batch-related data and content across Veeva applications and third-party solutions addresses the fundamental challenge of modern pharmaceutical manufacturing: achieving real-time visibility and compliance across increasingly complex supply chains and regulatory requirements.

Core Value Proposition: Centralized Intelligence

Batch Release Management operates on three foundational pillars that address the most pressing challenges in pharmaceutical batch release operations.

Aggregation: Unified Data Visibility

The Batch Release Dashboard provides centralized visibility into all batch-related activities, eliminating the information silos that traditionally complicate release decisions. This unified view aggregates data from quality systems, manufacturing execution systems, laboratory information management systems, and regulatory databases into a single interface.

Market Ship Decisions capability recognizes that modern pharmaceutical companies often release batches to multiple markets with varying regulatory requirements. The system enables release managers to make market-specific decisions based on local regulatory requirements and quality standards.

Multiple Decisions per Batch functionality acknowledges that complex batch release scenarios often require multiple approval stages or different approval criteria for different aspects of the batch. This capability enables granular control over release decisions while maintaining comprehensive audit trails.

Genealogy Aware Checks represent perhaps the most sophisticated feature, providing visibility into the complete history of materials and components used in batch production. This capability is essential for investigating quality issues and ensuring that upstream problems don’t affect downstream batches.

Automation: Reducing Manual Overhead

Disposition Document Set Auto-Creation eliminates the manual effort traditionally required to compile release documentation. The system automatically generates the complete set of documents required for batch release, ensuring consistency and reducing the risk of missing critical documentation.

Rules-Based Assignment automates the routing of release activities to appropriate personnel based on product type, market requirements, and organizational structure. This automation ensures that batches are reviewed by qualified personnel while optimizing workload distribution.

Due Dates Calculation automatically determines release timelines based on product requirements, market needs, and regulatory constraints. This capability helps organizations optimize inventory management while ensuring compliance with stability and expiry requirements.

Disposition Dependencies manage the complex relationships between different release activities, ensuring that activities are completed in the correct sequence and that dependencies are clearly understood by all stakeholders.

Optimization: Exception-Based Efficiency

Review by Exception focuses human attention on batches that require intervention while automatically processing routine releases. This approach significantly reduces the time required for batch release while ensuring that unusual situations receive appropriate attention.

Revisionable Plans enable organizations to maintain controlled flexibility in their batch release processes. Plans can be updated and versioned while maintaining full audit trails of changes and their rationale.

Plan Variation allows for material and site-specific customization while maintaining overall process consistency. This capability is particularly valuable for organizations manufacturing across multiple sites or handling diverse product portfolios.

Recent Enhancements: Addressing Real-World Complexity

The 2025 updates demonstrate Veeva’s understanding of the complex scenarios that batch release managers encounter in daily operations.

Quality Event Integration

Disposition Impact Field on Deviations and Lab Investigations creates direct linkage between quality events and batch release decisions. This enhancement ensures that quality issues are automatically considered in release decisions, reducing the risk that batches are released despite outstanding quality concerns.

Change Control Check for Affected Material provides automated verification that materials affected by change controls have been properly evaluated and approved for use. This capability is essential for maintaining product quality and regulatory compliance in dynamic manufacturing environments.

Genealogy and Traceability Enhancements

Genealogy Check represents a significant advancement in batch traceability. The system now examines all quality events, dispositions, and documents for every step in the material genealogy, providing comprehensive visibility into the quality history of released batches.

This capability is particularly valuable during regulatory inspections or quality investigations where complete traceability is required. The automated nature of these checks ensures that no relevant quality information is overlooked in release decisions.

Scalable Plan Management

Disposition Plan Variation addresses the challenge of managing batch release plans across thousands of materials while maintaining consistency. The system enables common checks and settings in parent plans that are shared across child plans, allowing standardization at the category level with specific variations for individual products.

For example, organizations can create parent plans for finished goods or raw materials and then create variations for specific products. This hierarchical approach dramatically reduces the administrative burden of maintaining release plans while ensuring appropriate customization for different product types.

Auto-Close Disposition Items Using Criteria reduces manual administrative tasks by automatically closing routine disposition items when predetermined criteria are met. This automation allows batch release personnel to focus on exception handling rather than routine administrative tasks.

Upcoming 2025 Developments

Manufacturing Intelligence

Change Control Check Using “As Designed” Bill of Materials introduces intelligent verification capabilities that compare actual batch composition against intended design. This check ensures that manufacturing deviations are properly identified and evaluated before batch release.

Material Genealogy and Bill of Materials Check provide comprehensive verification of material usage and composition. These capabilities ensure that only approved materials are used in production and that any substitutions or deviations are properly documented and approved.

Collaborative Release Management

Share Disposition enables collaborative release decisions across multiple stakeholders or organizational units. This capability is particularly valuable for organizations with distributed release authority or complex approval hierarchies.

Independent Disposition Check increases the granularity of check completion, allowing different aspects of batch release to be managed independently while maintaining overall process integrity. This enhancement provides greater flexibility in release workflows while ensuring comprehensive evaluation.

Site-Specific Optimization

Manufacturing Site Specific Plans recognize that different manufacturing sites may have different release requirements based on local regulations, capabilities, or product portfolios. This capability enables organizations to optimize release processes for specific sites while maintaining overall corporate standards.

2026 Vision: Regulatory Integration and Advanced Automation

Regulatory Intelligence

Regulatory Check Integration with RIM promises to revolutionize how organizations manage regulatory compliance in batch release. The system will monitor regulatory approvals for change controls across all markets, providing simple green or red indicators for each market.

This capability addresses one of the most complex aspects of global pharmaceutical operations: ensuring that batches are only released to markets where all relevant changes have been approved by local regulatory authorities. The automated nature of this check significantly reduces the risk of regulatory violations while simplifying the release process.

Supply Chain Intelligence

Supplier Qualification Check extends batch release intelligence to include supplier qualification status. This enhancement ensures that materials from unqualified or suspended suppliers cannot be used in released batches, providing an additional layer of supply chain risk management.

Advanced Automation

Change Control Check Automation will further reduce manual effort in batch release by automatically evaluating change control impacts on batch release decisions. This automation ensures that change controls are properly considered in release decisions without requiring manual intervention for routine scenarios.

Process Flexibility

Disposition Amendment introduces the ability to change disposition decisions with appropriate documentation and approval. This capability includes redline functionality to clearly document what changes were made and why, maintaining full audit trails while providing necessary flexibility for complex release scenarios.

Early but Promising

With seven customers actively using the system, Batch Release Management is still in the early adoption phase. However, the comprehensive feature set and sophisticated roadmap suggest that the system is positioning itself as the definitive solution for pharmaceutical batch release management.

The current customer base likely represents organizations with complex release requirements that traditional systems cannot address effectively. As the system matures and demonstrates value in these demanding environments, broader market adoption should follow.

Batch Release Management represents a fundamental shift from traditional batch release approaches toward intelligent, automated, and integrated release management. The combination of aggregation, automation, and optimization capabilities addresses the core challenges of modern pharmaceutical manufacturing while providing a foundation for future regulatory and operational evolution.

Organizations managing complex batch release operations should seriously evaluate current capabilities, while those with simpler requirements should monitor the system’s evolution. The 2026 regulatory integration capabilities alone could justify adoption for organizations operating in multiple global markets.

Learning from Fujifilm Biotechnologies: Standardizing Document Management and Beyond for Global Quality

The opportunity to hear from Fujifilm Biotechnologies about their approach to global quality standardization provided valuable insights into how world-class organizations tackle the fundamental challenges of harmonizing processes across diverse operations. Their presentation reinforced several critical principles while offering practical wisdom gained from their own transformation journey.

The Foundation: Transparency and Data Governance

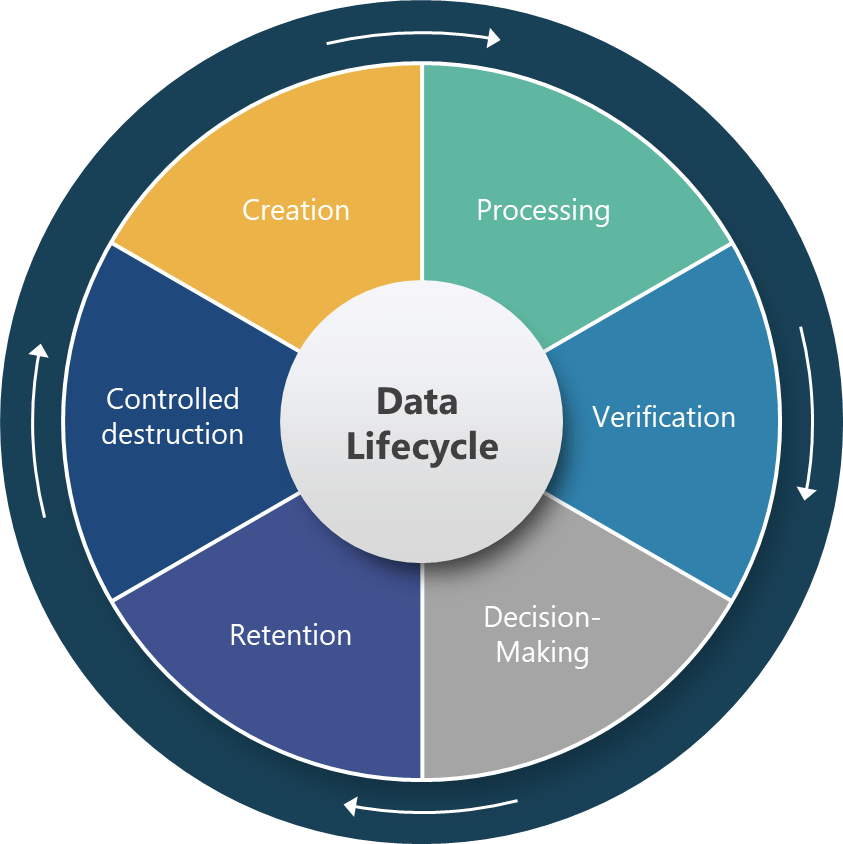

Fujifilm’s emphasis on transparency in data governance and harmonization of metadata struck me as foundational to their success. This focus recognizes that effective quality management depends not just on having the right processes, but on ensuring that data flows seamlessly across organizational boundaries and that everyone understands what that data means.

The stress on metadata harmonization is particularly insightful. Too often, organizations focus on standardizing processes while allowing inconsistent data definitions and structures to persist. Fujifilm’s approach suggests that metadata standardization may be as important as process standardization in achieving true global consistency.

Documents as the Strategic Starting Point

The observation that process standardization between sites fuels competitive edge resonates deeply with our own transformation experience. Fujifilm’s decision to focus on documents as “the classic way to start” validates an approach that many quality organizations instinctively understand—documents are core to how quality professionals think about their work.

Veeva’s strategic focus on QualityDocs as the foothold into their platform aligns perfectly with this insight. Documents represent the most tangible and universal aspect of quality management across different sites, regulatory jurisdictions, and organizational cultures. Starting with document standardization provides immediate value while creating the foundation for broader process harmonization.

This approach acknowledges that quality professionals across the globe share common document types—SOPs, specifications, protocols, reports—even when their specific processes vary. By standardizing document management first, organizations can achieve quick wins while building the infrastructure for more complex standardization efforts.

Overcoming System Migration Challenges

One of Fujifilm’s most practical insights addressed change management and the tendency for people to apply their last system experience to new systems. This observation captures a fundamental challenge in system implementations: users naturally try to recreate familiar workflows rather than embracing new capabilities.

Their solution—providing the right knowledge and insights upfront—emphasizes the importance of education over mere training. Rather than simply teaching users how to operate new systems, successful implementations help users understand why new approaches are better and how they can leverage enhanced capabilities.

This insight suggests that change management programs should focus as much on mindset transformation as on skill development. Users need to understand not just what to do differently, but why the new approach creates value they couldn’t achieve before.

Solving Operational Model Questions

The discussion of operating model questions such as business administration and timezone coverage highlighted often-overlooked practical challenges. Fujifilm’s recognition that global operations require thoughtful consideration of communication patterns and support models demonstrates mature thinking about operational sustainability.

The concept of well-worn paths of communication and setting up new ones connects to the idea of desire trails—the informal communication patterns that emerge naturally in organizations. Successful global standardization requires understanding these existing patterns while deliberately creating new pathways that support standardized processes.

This approach suggests that operational model design should be as deliberate as process design. Organizations need to explicitly plan how work will be coordinated across sites, timezones, and organizational boundaries rather than assuming that good processes will automatically create good coordination.

Organizational Change Management (OCM) as Strategy

Fujifilm’s focus on building desired outcomes into processes from the beginning represents sophisticated change management thinking. Rather than treating change management as an add-on activity, they integrate outcome definition into process design itself.

The emphasis on asking “how can this enable our business” throughout the implementation process ensures that standardization efforts remain connected to business value rather than becoming exercises in consistency for its own sake. This business-focused approach helps maintain stakeholder engagement and provides clear criteria for evaluating success.

The stress on good system discovery leading to good requirements acknowledges that many implementation failures stem from inadequate understanding of current state operations. Thorough discovery work ensures that standardization efforts address real operational challenges rather than theoretical improvements.

Sequence Matters: Harmonize First, Then Implement

One of Fujifilm’s most important insights was that harmonizing while implementing can be hard to do. Their recommendation to take the time to harmonize first, and then implement electronic tools challenges the common tendency to use system implementations as forcing mechanisms for harmonization.

This approach requires patience and upfront investment but likely produces better long-term results. When harmonization occurs before system implementation, the technology can be configured to support agreed-upon processes rather than trying to accommodate multiple conflicting approaches.

The sequential approach also allows organizations to resolve process conflicts through business discussions rather than technical compromises. Process harmonization becomes a business decision rather than a systems constraint, leading to better outcomes and stronger stakeholder buy-in.

Perhaps the most strategic insight was Fujifilm’s approach to business process ownership through global support with local business process owners working together as a community of practice. This model addresses one of the most challenging aspects of global standardization: maintaining consistency while accommodating local needs and knowledge.

The community of practice approach recognizes that effective process ownership requires both global perspective and local expertise. Global support provides consistency, resources, and best practice sharing, while local process owners ensure that standardized approaches work effectively in specific operational contexts.

This model also creates natural mechanisms for continuous improvement. Local process owners can identify improvement opportunities and share them through the community of practice, while global support can evaluate and disseminate successful innovations across the network.

Key Takeaways for Global Quality Organizations

Fujifilm’s experience offers several actionable insights for organizations pursuing global quality standardization:

- Start with Documents: Document standardization provides immediate value while building infrastructure for broader harmonization efforts.

- Prioritize Metadata Harmonization: Consistent data definitions may be as important as consistent processes for achieving true standardization.

- Sequence Implementation Carefully: Harmonize processes before implementing technology to avoid technical compromises that undermine business objectives.

- Design Operating Models Deliberately: Plan communication patterns and support structures as carefully as process flows.

- Integrate Change Management into Process Design: Build desired outcomes and business enablement questions into processes from the beginning.

- Create Communities of Practice: Balance global consistency with local expertise through structured collaboration models.

Fujifilm’s approach suggests that successful global quality standardization requires sophisticated thinking about organizational change, not just process improvement. The integration of change management principles, operating model design, and community-building activities into standardization efforts demonstrates mature understanding of what it takes to achieve lasting transformation.

For quality organizations embarking on global standardization journeys, Fujifilm’s insights provide a valuable roadmap that goes beyond technical implementation to address the fundamental challenges of creating consistent, effective quality operations across diverse organizational contexts.

And That’s a Wrap

This was the last session of the day.