In the pharmaceutical industry, qualification and validation is a critical process to ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of products. Over the years, several models have emerged to guide efforts for facilities, utilities, systems, equipment, and processes. This blog post will explore three prominent models: the 4Q model, the V-model, and the W-model. We’ll also discuss relevant regulatory guidelines and industry standards.

The 4Q Model

The 4Q model is a widely accepted approach to qualification in the pharmaceutical industry. It consists of four stages:

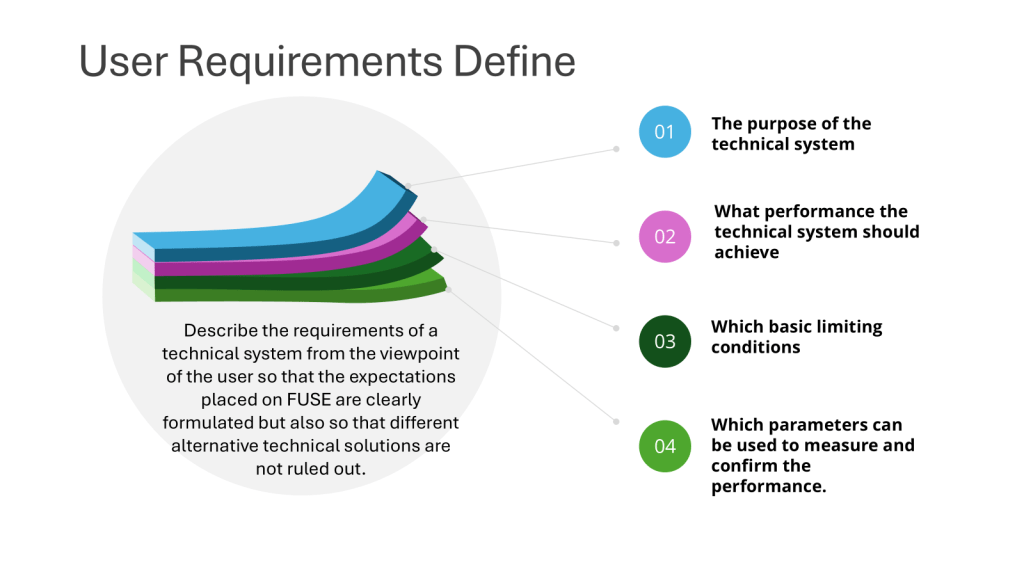

- Design Qualification (DQ): This initial stage focuses on documenting that the design of facilities, systems, and equipment is suitable for the intended purpose. DQ should verify that the proposed design of facilities, systems, and equipment is suitable for the intended purpose. The requirements of the user requirements specification (URS) should be verified during DQ.

- Installation Qualification (IQ): IQ verifies that the equipment or system has been properly installed according to specifications. IQ should include verification of the correct installation of components and instrumentation against engineering drawings and specifications — the pre-defined criteria.

- Operational Qualification (OQ): This stage demonstrates that the equipment or system operates as intended across the expected operating ranges. OQ should ensure the system is operating as designed, confirming the upper and lower operating limits, and/or “worst case” conditions. Depending on the complexity of the equipment, OQ may be performed as a combined Installation/Operation Qualification (IOQ). The completion of a successful OQ should allow for the finalization of standard operating and cleaning procedures, operator training, and preventative maintenance requirements.

- Performance Qualification (PQ): PQ confirms that the equipment or system consistently performs as expected under routine production conditions. PQ should normally follow the successful completion of IQ and OQ, though in some cases, it may be appropriate to perform PQ in conjunction with OQ or Process Validation. PQ should include tests using production materials, qualified substitutes, or simulated products proven to have equivalent behavior under normal operating conditions with worst-case batch sizes. The extent of PQ tests depends on the results from development and the frequency of sampling during PQ should be justified.

The V-Model

The V-model, introduced by the International Society of Pharmaceutical Engineers (ISPE) in 1994, provides a visual representation of the qualification process:

- The left arm of the “V” represents the planning and specification phases.

- The bottom of the “V” represents the build and unit testing phases.

- The right arm represents the execution and qualification phases.

This model emphasizes the relationship between each development stage and its corresponding testing phase, promoting a systematic approach to validation.

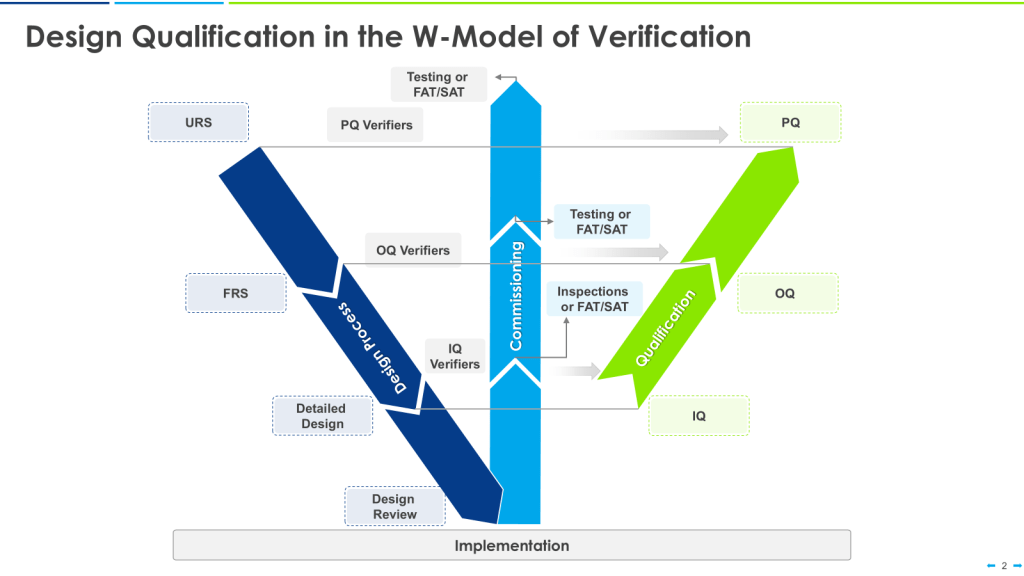

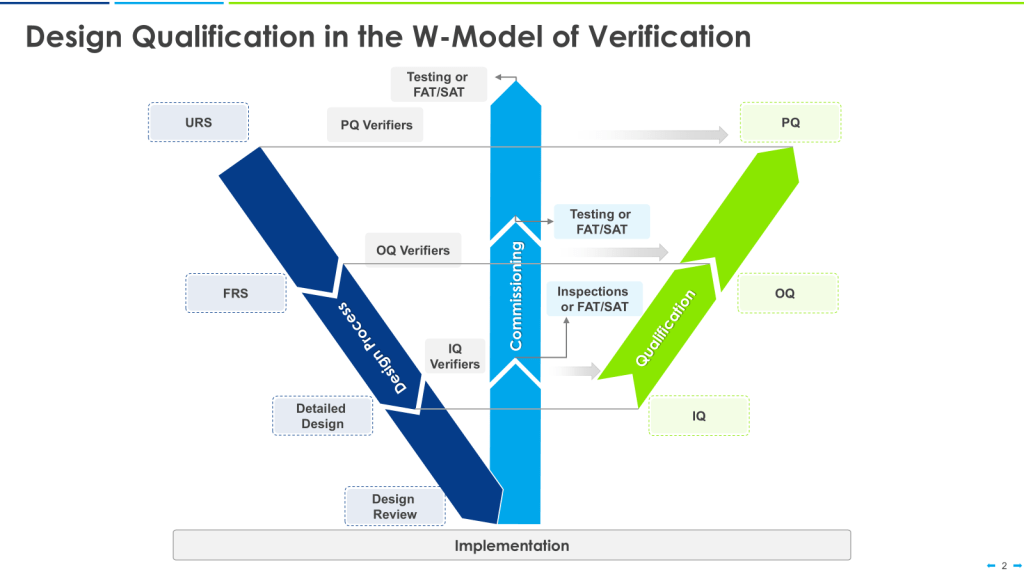

The W-Model

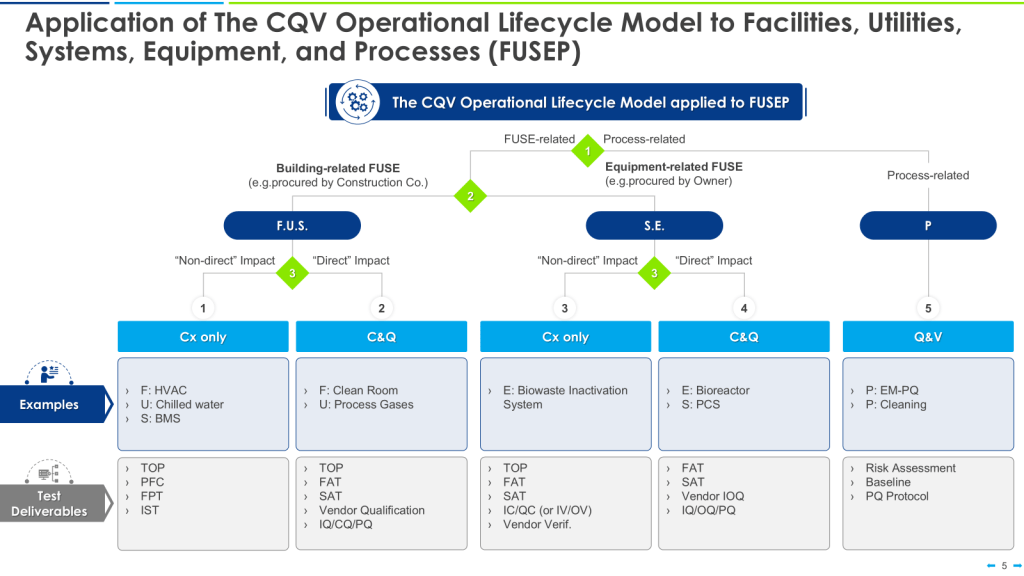

The W-model is an extension of the V-model that explicitly incorporates commissioning activities:

- The first “V” represents the traditional V-model stages.

- The center portion of the “W” represents commissioning activities.

- The second “V” represents qualification activities.

This model provides more granularity to what is identified as “verification testing,” including both commissioning (e.g., FAT, SAT) and qualification testing (IQ, OQ, PQ).

| Aspect | 4Q Model | V-Model | W-Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | DQ, IQ, OQ, PQ | User Requirements, Functional Specs, Design Specs, IQ, OQ, PQ | User Requirements, Functional Specs, Design Specs, Commissioning, IQ, OQ, PQ |

| Focus | Sequential qualification stages | Linking development and testing phases | Integrating commissioning with qualification |

| Flexibility | Moderate | High | High |

| Emphasis on Commissioning | Limited | Limited | Explicit |

| Risk-based Approach | Can be incorporated | Can be incorporated | Inherently risk-based |

Where Qualifcation Fits into the Regulatory Landscape and Industry Guidelines

WHO Guidelines

The World Health Organization (WHO) provides guidance on validation and qualification in its “WHO good manufacturing practices for pharmaceutical products: main principles”. While not explicitly endorsing a specific model, WHO emphasizes the importance of a systematic approach to validation.

EMA Guidelines

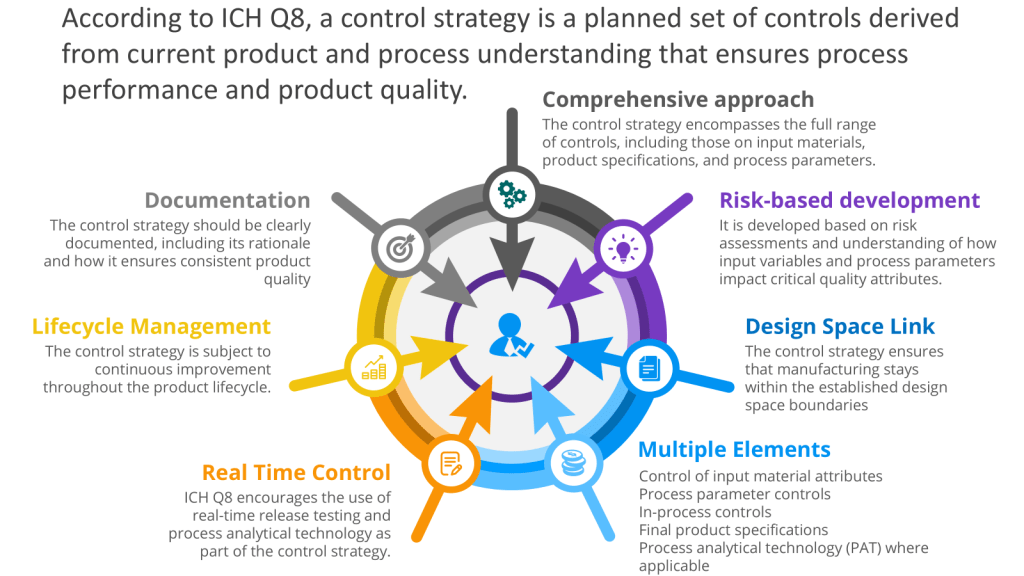

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has published guidelines on process validation for the manufacture of biotechnology-derived active substances and data to be provided in regulatory submissions. These guidelines align with the principles of ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10, promoting a lifecycle approach to validation.

Annex 15 provides guidance on qualification and validation in pharmaceutical manufacturing. Regarding Design Qualification (DQ), Installation Qualification (IQ), Operational Qualification (OQ), and Performance Qualification (PQ) which is pretty much either the V or W model.

Annex 15 emphasizes a lifecycle approach to validation, considering all stages from initial development of the user requirements specification through to the end of use of the equipment, facility, utility, or system. The main stages of qualification and some suggested criteria are indicated as a “could” option, allowing for flexibility in approach.

Annex 15 provides a structured yet flexible approach to qualification, allowing pharmaceutical manufacturers to adapt their validation strategies to the complexity of their equipment and processes while maintaining compliance with regulatory requirements.

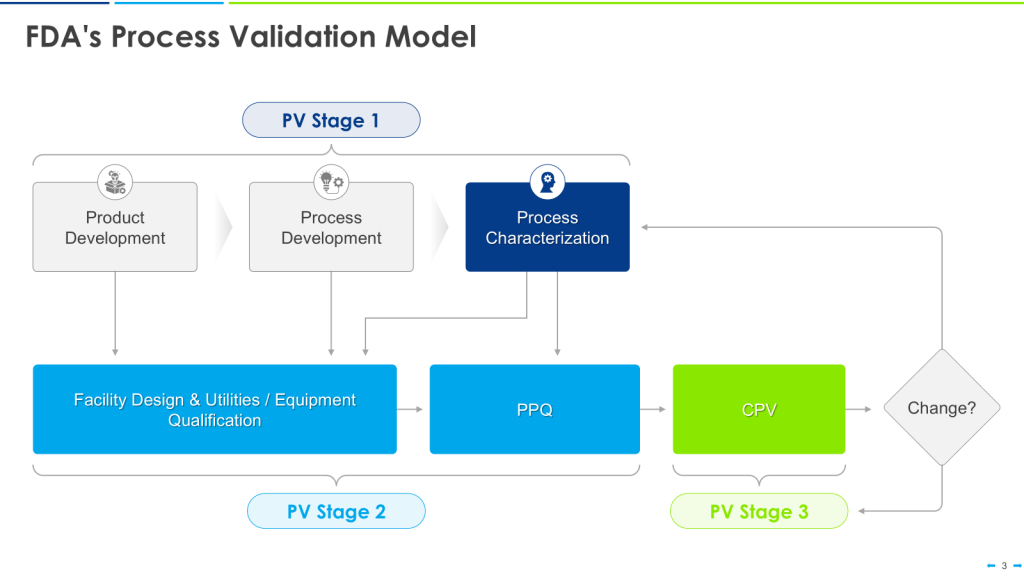

FDA Guidance

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued its “Guidance for Industry: Process Validation: General Principles and Practices” in 2011. This guidance emphasizes a lifecycle approach to process validation, consisting of three stages: process design, process qualification, and continued process verification.

ASTM E2500

ASTM E2500, “Standard Guide for Specification, Design, and Verification of Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing Systems and Equipment,” provides a risk-based approach to validation. It introduces the concept of “verification” as an alternative to traditional qualification steps, allowing for more flexible and efficient validation processes.

ISPE Guidelines

The International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE) has published several baseline guides and good practice guides that complement regulatory requirements. These include guides on commissioning and qualification, as well as on the implementation of ASTM E2500.

Baseline Guide Vol 5: Commissioning & Qualification (Second Edition)

This guide offers practical guidance on implementing a science and risk-based approach to commissioning and qualification (C&Q). Key aspects include:

- Applying Quality Risk Management to C&Q

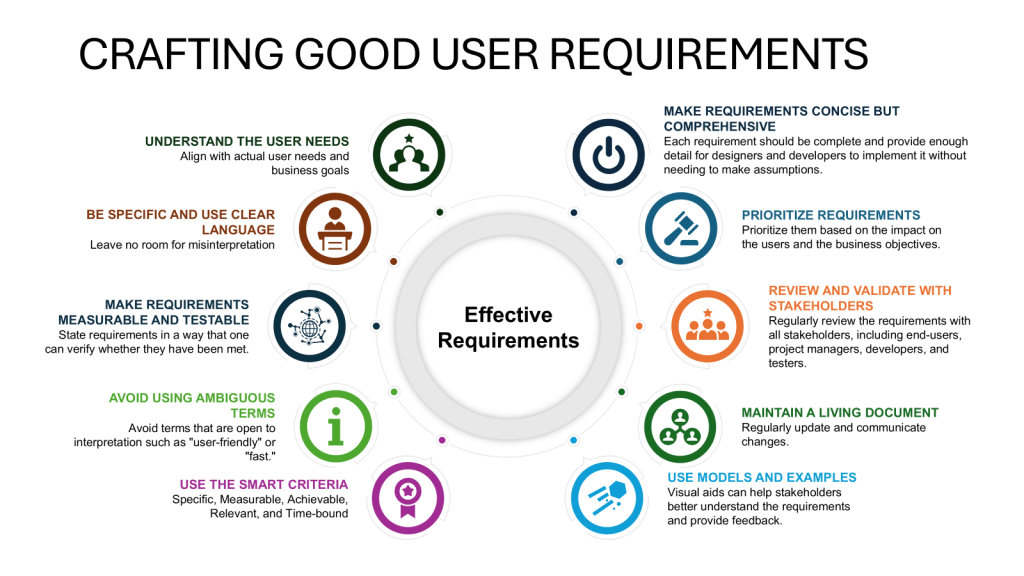

- Best practices for User Requirements Specification, Design Review, Design Qualification, and acceptance/release

- Efficient use of change management to support C&Q

- Good Engineering Practice documentation standards

The guide aims to simplify and improve the C&Q process by integrating concepts from regulatory guidances (EMA, FDA, ISO) and replacing certain aspects of previous approaches with Quality Risk Management and Good Engineering Practice concepts.

Conclusion

While the 4Q, V, and W models provide structured approaches to validation, the pharmaceutical industry is increasingly moving towards risk-based and science-driven methodologies. Regulatory agencies and industry organizations are promoting flexible approaches that focus on critical aspects of product quality and patient safety.

By leveraging guidelines such as ASTM E2500 and ISPE recommendations, pharmaceutical companies can develop efficient validation strategies that meet regulatory requirements while optimizing resources. The key is to understand the principles behind these models and guidelines and apply them in a way that best suits the specific needs of each facility, system, or process.