The United States Pharmacopeia’s proposed revision of General Chapter <1225> Validation of Compendial Procedures, published in Pharmacopeial Forum 51(6), represents the continuation of a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize analytical method validation—moving from static demonstration of compliance toward dynamic lifecycle management of analytical capability.

This gets to the heart of a challenge us to think differently about what validation actually means. The revised chapter introduces concepts like reportable result, fitness for purpose, replication strategy, and combined evaluation of accuracy and precision that force us to confront uncomfortable questions: What are we actually validating? For what purpose? Under what conditions? And most critically—how do we know our analytical procedures remain fit for purpose once validation is “complete”?

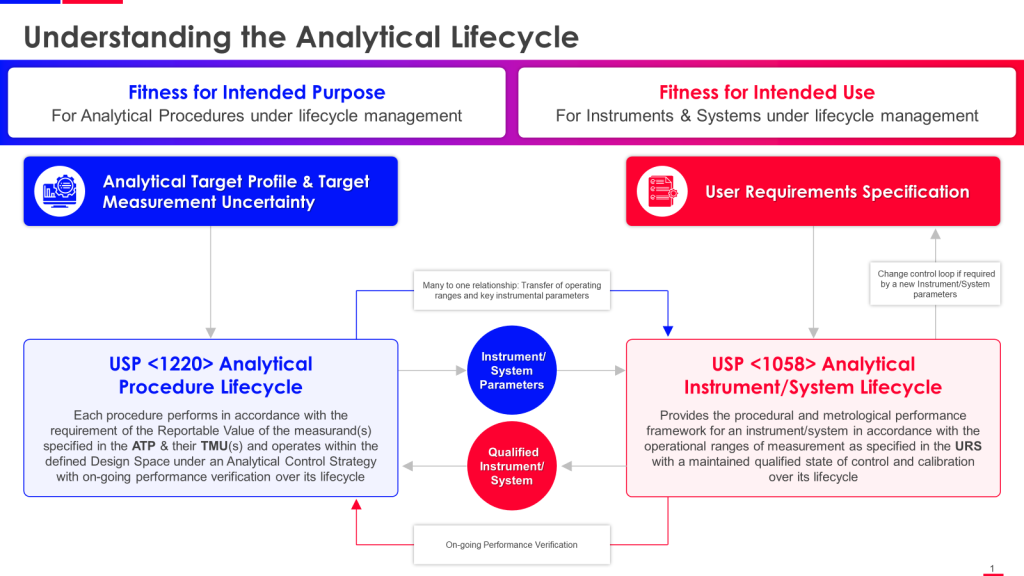

The timing of this revision is deliberate. USP is working to align <1225> more closely with ICH Q2(R2) Validation of Analytical Procedures and ICH Q14 Analytical Procedure Development, both finalized in 2023. Together with the already-official USP <1220> Analytical Procedure Life Cycle (May 2022), these documents form an interconnected framework that demands we abandon the comfortable fiction that validation is a discrete event rather than an ongoing commitment to analytical quality.

Traditional validation approaches cn create the illusion of control without delivering genuine analytical reliability. Methods that “passed validation” fail when confronted with real-world variability. System suitability tests that looked rigorous on paper prove inadequate for detecting performance drift. Acceptance criteria established during development turn out to be disconnected from what actually matters for product quality decisions.

The revised USP <1225> offers conceptual tools to address these failures—if we’re willing to use them honestly rather than simply retrofitting compliance theater onto existing practices. This post explores what the revision actually says, how it relates to ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, and what it demands from quality leaders who want to build genuinely robust analytical systems rather than just impressive validation packages.

The Validation Paradigm Shift: From Compliance Theater to Lifecycle Management

Traditional analytical method validation follows a familiar script. We conduct studies demonstrating acceptable performance for specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, range, and (depending on the method category) detection and quantitation limits. We generate validation reports showing data meets predetermined acceptance criteria. We file these reports in regulatory submission dossiers or archive them for inspection readiness. Then we largely forget about them until transfer, revalidation, or regulatory scrutiny forces us to revisit the method’s performance characteristics.

This approach treats validation as what Sidney Dekker would call “safety theater”—a performance of rigor that may or may not reflect the method’s actual capability to generate reliable results under routine conditions. The validation study represents work-as-imagined: controlled experiments conducted by experienced analysts using freshly prepared standards and reagents, with carefully managed environmental conditions and full attention to procedural details. What happens during routine testing—work-as-done—often looks quite different.

The lifecycle perspective championed by ICH Q14 and USP <1220> fundamentally challenges this validation-as-event paradigm. From a lifecycle view, validation becomes just one stage in a continuous process of ensuring analytical fitness for purpose. Method development (Stage 1 in USP <1220>) generates understanding of how method parameters affect performance. Validation (Stage 2) confirms the method performs as intended under specified conditions. But the critical innovation is Stage 3—ongoing performance verification that treats method capability as dynamic rather than static.

The revised USP <1225> attempts to bridge these worldviews. It maintains the structure of traditional validation studies while introducing concepts that only make sense within a lifecycle framework. Reportable result—the actual output of the analytical procedure that will be used for quality decisions—forces us to think beyond individual measurements to what we’re actually trying to accomplish. Fitness for purpose demands we articulate specific performance requirements linked to how results will be used, not just demonstrate acceptable performance against generic criteria. Replication strategy acknowledges that the variability observed during validation must reflect the variability expected during routine use.

These aren’t just semantic changes. They represent a shift from asking “does this method meet validation acceptance criteria?” to “will this method reliably generate results adequate for their intended purpose under actual operating conditions?” That second question is vastly more difficult to answer honestly, which is why many organizations will be tempted to treat the new concepts as compliance checkboxes rather than genuine analytical challenges.

I’ve advocated on this blog for falsifiable quality systems—systems that make testable predictions that could be proven wrong through empirical observation. The lifecycle validation paradigm, properly implemented, is inherently more falsifiable than traditional validation. Instead of a one-time demonstration that a method “works,” lifecycle validation makes an ongoing claim: “This method will continue to generate results of acceptable quality when operated within specified conditions.” That claim can be tested—and potentially falsified—every time the method is used. The question is whether we’ll design our Stage 3 performance verification systems to actually test that claim or simply monitor for obviously catastrophic failures.

Core Concepts in the Revised USP <1225>

The revised chapter introduces several concepts that deserve careful examination because they change not just what we do but how we think about analytical validation.

Reportable Result: The Target That Matters

Reportable result may be the most consequential new concept in the revision. It’s defined as the final analytical result that will be reported and used for quality decisions—not individual sample preparations, not replicate injections, but the actual value that appears on a Certificate of Analysis or stability report.

This distinction matters enormously because validation historically focused on demonstrating acceptable performance of individual measurements without always considering how those measurements would be combined to generate reportable values. A method might show excellent repeatability for individual injections while exhibiting problematic variability when the full analytical procedure—including sample preparation, multiple preparations, and averaging—is executed under intermediate precision conditions.

The reportable result concept forces us to validate what we actually use. If our SOP specifies reporting the mean of duplicate sample preparations, each prepared in duplicate and injected in triplicate, then validation should evaluate the precision and accuracy of that mean value, not just the repeatability of individual injections. This seems obvious when stated explicitly, but review your validation protocols and ask honestly: are you validating the reportable result or just demonstrating that the instrument performs acceptably?

This concept aligns perfectly with the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) from ICH Q14, which specifies required performance characteristics for the reportable result. Together, these frameworks push us toward outcome-focused validation rather than activity-focused validation. The question isn’t “did we complete all the required validation experiments?” but “have we demonstrated that the reportable results this method generates will be adequate for their intended use?”

Fitness for Purpose: Beyond Checkbox Validation

Fitness for purpose appears throughout the revised chapter as an organizing principle for validation strategy. But what does it actually mean beyond regulatory rhetoric?

In the falsifiable quality systems framework I’ve been developing, fitness for purpose requires explicit articulation of how analytical results will be used and what performance characteristics are necessary to support those decisions. An assay method used for batch release needs different performance characteristics than the same method used for stability trending. A method measuring a critical quality attribute directly linked to safety or efficacy requires more stringent validation than a method monitoring a process parameter with wide acceptance ranges.

The revised USP <1225> pushes toward risk-based validation strategies that match validation effort to analytical criticality and complexity. This represents a significant shift from the traditional category-based approach (Categories I-IV) that prescribed specific validation parameters based on method type rather than method purpose.

However, fitness for purpose creates interpretive challenges that could easily devolve into justification for reduced rigor. Organizations might claim methods are “fit for purpose” with minimal validation because “we’ve been using this method for years without problems.” This reasoning commits what I call the effectiveness fallacy—assuming that absence of detected failures proves adequate performance. In reality, inadequate analytical methods often fail silently, generating subtly inaccurate results that don’t trigger obvious red flags but gradually degrade our understanding of product quality.

True fitness for purpose requires explicit, testable claims about method performance: “This method will detect impurity X at levels down to 0.05% with 95% confidence” or “This assay will measure potency within ±5% of true value under normal operating conditions.” These are falsifiable statements that ongoing performance verification can test. Vague assertions that methods are “adequate” or “appropriate” are not.

Replication Strategy: Understanding Real Variability

The replication strategy concept addresses a fundamental disconnect in traditional validation: the mismatch between how we conduct validation experiments and how we’ll actually use the method. Validation studies often use simplified replication schemes optimized for experimental efficiency rather than reflecting the full procedural reality of routine testing.

The revised chapter emphasizes that validation should employ the same replication strategy that will be used for routine sample analysis to generate reportable results. If your SOP calls for analyzing samples in duplicate on separate days, validation should incorporate that time-based variability. If sample preparation involves multiple extraction steps that might be performed by different analysts, intermediate precision studies should capture that source of variation.

This requirement aligns validation more closely with work-as-done rather than work-as-imagined. But it also makes validation more complex and time-consuming. Organizations accustomed to streamlined validation protocols will face pressure to either expand their validation studies or simplify their routine testing procedures to match validation replication strategies.

From a quality systems perspective, this tension reveals important questions: Have we designed our analytical procedures to be unnecessarily complex? Are we requiring replication beyond what’s needed for adequate measurement uncertainty? Or conversely, are our validation replication schemes unrealistically simplified compared to the variability we’ll encounter during routine use?

The replication strategy concept forces these questions into the open rather than allowing validation and routine operation to exist in separate conceptual spaces.

Statistical Intervals: Combined Accuracy and Precision

Perhaps the most technically sophisticated addition in the revised chapter is guidance on combined evaluation of accuracy and precision using statistical intervals. Traditional validation treats these as separate performance characteristics evaluated through different experiments. But in reality, what matters for reportable results is the total error combining both bias (accuracy) and variability (precision).

The chapter describes approaches for computing statistical intervals that account for both accuracy and precision simultaneously. These intervals can then be compared against acceptance criteria to determine if the method is validated. If the computed interval falls completely within acceptable limits, the method demonstrates adequate performance for both characteristics together.

This approach is more scientifically rigorous than separate accuracy and precision evaluations because it recognizes that these characteristics interact. A highly precise method with moderate bias might generate reportable results within acceptable ranges, while a method with excellent accuracy but poor precision might not. Traditional validation approaches that evaluate these characteristics separately can miss such interactions.

However, combined evaluation requires more sophisticated statistical expertise than many analytical laboratories possess. The chapter provides references to USP <1210> Statistical Tools for Procedure Validation, which describes appropriate methodologies, but implementation will challenge organizations lacking strong statistical support for their analytical functions.

This creates risk of what I’ve called procedural simulation—going through the motions of applying advanced statistical methods without genuine understanding of what they reveal about method performance. Quality leaders need to ensure that if their teams adopt combined accuracy-precision evaluation approaches, they actually understand the results rather than just feeding data into software and accepting whatever output emerges.

Knowledge Management: Building on What We Know

The revised chapter emphasizes knowledge management more explicitly than previous versions, acknowledging that validation doesn’t happen in isolation from development activities and prior experience. Data generated during method development, platform knowledge from similar methods, and experience with related products all constitute legitimate inputs to validation strategy.

This aligns with ICH Q14’s enhanced approach and ICH Q2(R2)’s acknowledgment that development data can support validation. But it also creates interpretive challenges around what constitutes adequate prior knowledge and how to appropriately leverage it.

In my experience leading quality organizations, knowledge management is where good intentions often fail in practice. Organizations claim to be “leveraging prior knowledge” while actually just cutting corners on validation studies. Platform approaches that worked for previous products get applied indiscriminately to new products with different critical quality attributes. Development data generated under different conditions gets repurposed for validation without rigorous evaluation of its applicability.

Effective knowledge management requires disciplined documentation of what we actually know (with supporting evidence), explicit identification of knowledge gaps, and honest assessment of when prior experience is genuinely applicable versus superficially similar. The revised USP <1225> provides the conceptual framework for this discipline but can’t force organizations to apply it honestly.

Comparing the Frameworks: USP <1225>, ICH Q2(R2), and ICH Q14

Understanding how these three documents relate—and where they diverge—is essential for quality professionals trying to build coherent analytical validation programs.

Analytical Target Profile: Q14’s North Star

ICH Q14 introduced the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) as a prospective description of performance characteristics needed for an analytical procedure to be fit for its intended purpose. The ATP specifies what needs to be measured (the quality attribute), required performance criteria (accuracy, precision, specificity, etc.), and the anticipated performance based on product knowledge and regulatory requirements.

The ATP concept doesn’t explicitly appear in revised USP <1225>, though the chapter’s emphasis on fitness for purpose and reportable result requirements creates conceptual space for ATP-like thinking. This represents a subtle tension between the documents. ICH Q14 treats the ATP as foundational for both enhanced and minimal approaches to method development, while USP <1225> maintains its traditional structure without explicitly requiring ATP documentation.

In practice, this means organizations can potentially comply with revised USP <1225> without fully embracing the ATP concept. They can validate methods against acceptance criteria without articulating why those particular criteria are necessary for the reportable result’s intended use. This risks perpetuating validation-as-compliance-exercise rather than forcing honest engagement with whether methods are actually adequate.

Quality leaders serious about lifecycle validation should treat the ATP as essential even when working with USP <1225>, using it to bridge method development, validation, and ongoing performance verification. The ATP makes explicit what traditional validation often leaves implicit—the link between analytical performance and product quality requirements.

Performance Characteristics: Evolution from Q2(R1) to Q2(R2)

ICH Q2(R2) substantially revises the performance characteristics framework from the 1996 Q2(R1) guideline. Key changes include:

Specificity/Selectivity are now explicitly addressed together rather than treated as equivalent. The revision acknowledges these terms have been used inconsistently across regions and provides unified definitions. Specificity refers to the ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of expected components, while selectivity relates to the ability to measure the analyte in a complex mixture. In practice, most analytical methods need to demonstrate both, and the revised guidance provides clearer expectations for this demonstration.

Range now explicitly encompasses non-linear calibration models, acknowledging that not all analytical relationships follow simple linear functions. The guidance describes how to demonstrate that methods perform adequately across the reportable range even when the underlying calibration relationship is non-linear. This is particularly relevant for biological assays and certain spectroscopic techniques where non-linearity is inherent to the measurement principle.

Accuracy and Precision can be evaluated separately or through combined approaches, as discussed earlier. This flexibility accommodates both traditional methodology and more sophisticated statistical approaches while maintaining the fundamental requirement that both characteristics be adequate for intended use.

Revised USP <1225> incorporates these changes while maintaining its compendial focus. The chapter continues to reference validation categories (I-IV) as a familiar framework while noting that risk-based approaches considering the method’s intended use should guide validation strategy. This creates some conceptual tension—the categories imply that method type determines validation requirements, while fitness-for-purpose thinking suggests that method purpose should drive validation design.

Organizations need to navigate this tension thoughtfully. The categories provide useful starting points for validation planning, but they shouldn’t become straitjackets preventing appropriate customization based on specific analytical needs and risks.

The Enhanced Approach: When and Why

ICH Q14 distinguishes between minimal and enhanced approaches to analytical procedure development. The minimal approach uses traditional univariate optimization and risk assessment based on prior knowledge and analyst experience. The enhanced approach employs systematic risk assessment, design of experiments, establishment of parameter ranges (PARs or MODRs), and potentially multivariate analysis.

The enhanced approach offers clear advantages: deeper understanding of method performance, identification of critical parameters and their acceptable ranges, and potentially more robust control strategies that can accommodate changes without requiring full revalidation. But it also demands substantially more development effort, statistical expertise, and time.

Neither ICH Q2(R2) nor revised USP <1225> mandates the enhanced approach, though both acknowledge it as a valid strategy. This leaves organizations facing difficult decisions about when enhanced development is worth the investment. In my experience, several factors should drive this decision:

- Product criticality and lifecycle stage: Biologics products with complex quality profiles and long commercial lifecycles benefit substantially from enhanced analytical development because the upfront investment pays dividends in robust control strategies and simplified change management.

- Analytical complexity: Multivariate spectroscopic methods (NIR, Raman, mass spectrometry) are natural candidates for enhanced approaches because their complexity demands systematic exploration of parameter spaces that univariate approaches can’t adequately address.

- Platform potential: When developing methods that might be applied across multiple products, enhanced approaches can generate knowledge that benefits the entire platform, amortizing development costs across the portfolio.

- Regulatory landscape: Biosimilar programs and products in competitive generic spaces may benefit from enhanced approaches that strengthen regulatory submissions and simplify lifecycle management in response to originator changes.

However, enhanced approaches can also become expensive validation theater if organizations go through the motions of design of experiments and parameter range studies without genuine commitment to using the resulting knowledge for method control and change management. I’ve seen impressive MODRs filed in regulatory submissions that are then completely ignored during commercial manufacturing because operational teams weren’t involved in development and don’t understand or trust the parameter ranges.

The decision between minimal and enhanced approaches should be driven by honest assessment of whether the additional knowledge generated will actually improve method performance and lifecycle management, not by belief that “enhanced” is inherently better or that regulators will be impressed by sophisticated development.

Validation Categories vs Risk-Based Approaches

USP <1225> has traditionally organized validation requirements using four method categories:

- Category I: Methods for quantitation of major components (assay methods)

- Category II: Methods for quantitation of impurities and degradation products

- Category III: Methods for determination of performance characteristics (dissolution, drug release)

- Category IV: Identification tests

Each category specifies which performance characteristics require evaluation. This framework provides clarity and consistency, making it easy to design validation protocols for common method types.

However, the category-based approach can create perverse incentives. Organizations might design methods to fit into categories with less demanding validation requirements rather than choosing the most appropriate analytical approach for their specific needs. A method capable of quantitating impurities might be deliberately operated only as a limit test (Category II modified) to avoid full quantitation validation requirements.

The revised chapter maintains the categories while increasingly emphasizing that fitness for purpose should guide validation strategy. This creates interpretive flexibility that can be used constructively or abused. Quality leaders need to ensure their teams use the categories as starting points for validation design, not as rigid constraints or opportunities for gaming the system.

Risk-based validation asks different questions than category-based approaches: What decisions will be made using this analytical data? What happens if results are inaccurate or imprecise beyond acceptable limits? How critical is this measurement to product quality and patient safety? These questions should inform validation design regardless of which traditional category the method falls into.

Specificity/Selectivity: Terminology That Matters

The evolution of specificity/selectivity terminology across these documents deserves attention because terminology shapes how we think about analytical challenges. ICH Q2(R1) treated the terms as equivalent, leading to regional confusion as different pharmacopeias and regulatory authorities developed different preferences.

ICH Q2(R2) addresses this by defining both terms clearly and acknowledging they address related but distinct aspects of method performance. Specificity is the ability to assess the analyte unequivocally—can we be certain our measurement reflects only the intended analyte and not interference from other components? Selectivity is the ability to measure the analyte in the presence of other components—can we accurately quantitate our analyte even in a complex matrix?

For monoclonal antibody product characterization, for instance, a method might be specific for the antibody molecule versus other proteins but show poor selectivity among different glycoforms or charge variants. Distinguishing these concepts helps us design studies that actually demonstrate what we need to know rather than generically “proving the method is specific.”

Revised USP <1225> adopts the ICH Q2(R2) terminology while acknowledging that compendial procedures typically focus on specificity because they’re designed for relatively simple matrices (standards and reference materials). The chapter notes that when compendial procedures are applied to complex samples like drug products, selectivity may need additional evaluation during method verification or extension.

This distinction has practical implications for how we think about method transfer and method suitability. A method validated for drug substance might require additional selectivity evaluation when applied to drug product, even though the fundamental specificity has been established. Recognizing this prevents the false assumption that validation automatically confers suitability for all potential applications.

The Three-Stage Lifecycle: Where USP <1220>, <1225>, and ICH Guidelines Converge

The analytical procedure lifecycle framework provides the conceptual backbone for understanding how these various guidance documents fit together. USP <1220> explicitly describes three stages:

Stage 1: Procedure Design and Development

This stage encompasses everything from initial selection of analytical technique through systematic development and optimization to establishment of an analytical control strategy. ICH Q14 provides detailed guidance for this stage, describing both minimal and enhanced approaches.

Key activities include:

- Knowledge gathering: Understanding the analyte, sample matrix, and measurement requirements based on the ATP or intended use

- Risk assessment: Identifying analytical procedure parameters that might impact performance, using tools from ICH Q9

- Method optimization: Systematically exploring parameter spaces through univariate or multivariate experiments

- Robustness evaluation: Understanding how method performance responds to deliberate variations in parameters

- Analytical control strategy: Establishing set points, acceptable ranges (PARs/MODRs), and system suitability criteria

Stage 1 generates the knowledge that makes Stage 2 validation more efficient and Stage 3 performance verification more meaningful. Organizations that short-cut development—rushing to validation with poorly understood methods—pay for those shortcuts through validation failures, unexplained variability during routine use, and inability to respond effectively to performance issues.

The causal reasoning approach I’ve advocated for investigations applies equally to method development. When development experiments produce unexpected results, the instinct is often to explain them away or adjust conditions to achieve desired outcomes. But unexpected results during development are opportunities to understand causal mechanisms governing method performance. Methods developed with genuine understanding of these mechanisms prove more robust than methods optimized through trial and error.

Stage 2: Procedure Performance Qualification (Validation)

This is where revised USP <1225> and ICH Q2(R2) provide detailed guidance. Stage 2 confirms that the method performs as intended under specified conditions, generating reportable results of adequate quality for their intended use.

The knowledge generated in Stage 1 directly informs Stage 2 protocol design. Risk assessment identifies which performance characteristics need most rigorous evaluation. Robustness studies reveal which parameters need tight control versus which have wide acceptable ranges. The analytical control strategy defines system suitability criteria and measurement conditions.

However, validation historically has been treated as disconnected from development, with validation protocols designed primarily to satisfy regulatory expectations rather than genuinely confirm method fitness. The revised documents push toward more integrated thinking—validation should test the specific knowledge claims generated during development.

From a falsifiable systems perspective, validation makes explicit predictions about method performance: “When operated within these conditions, this method will generate results meeting these performance criteria.” Stage 3 exists to continuously test whether those predictions hold under routine operating conditions.

Organizations that treat validation as a compliance hurdle rather than a genuine test of method fitness often discover that methods “pass validation” but perform poorly in routine use. The validation succeeded at demonstrating compliance but failed to establish that the method would actually work under real operating conditions with normal analyst variability, standard material lot changes, and equipment variations.

Stage 3: Continued Procedure Performance Verification

Stage 3 is where lifecycle validation thinking diverges most dramatically from traditional approaches. Once a method is validated and in routine use, traditional practice involved occasional revalidation driven by changes or regulatory requirements, but no systematic ongoing verification of performance.

USP <1220> describes Stage 3 as continuous performance verification through routine monitoring of performance-related data. This might include:

- System suitability trending: Not just pass/fail determination but statistical trending to detect performance drift

- Control charting: Monitoring QC samples, reference standards, or replicate analyses to track method stability

- Comparative testing: Periodic evaluation against orthogonal methods or reference laboratories

- Investigation of anomalous results: Treating unexplained variability or atypical results as potential signals of method performance issues

Stage 3 represents the “work-as-done” reality of analytical methods—how they actually perform under routine conditions with real samples, typical analysts, normal equipment status, and unavoidable operational variability. Methods that looked excellent during validation (work-as-imagined) sometimes reveal limitations during Stage 3 that weren’t apparent in controlled validation studies.

Neither ICH Q2(R2) nor revised USP <1225> provides detailed Stage 3 guidance. This represents what I consider the most significant gap in the current guidance landscape. We’ve achieved reasonable consensus around development (ICH Q14) and validation (ICH Q2(R2), USP <1225>), but Stage 3—arguably the longest and most important phase of the analytical lifecycle—remains underdeveloped from a regulatory guidance perspective.

Organizations serious about lifecycle validation need to develop robust Stage 3 programs even without detailed regulatory guidance. This means defining what ongoing verification looks like for different method types and criticality levels, establishing monitoring systems that generate meaningful performance data, and creating processes that actually respond to performance trending before methods drift into inadequate performance.

Practical Implications for Quality Professionals

Understanding what these documents say matters less than knowing how to apply their principles to build better analytical quality systems. Several practical implications deserve attention.

Moving Beyond Category I-IV Thinking

The validation categories provided useful structure when analytical methods were less diverse and quality systems were primarily compliance-focused. But modern pharmaceutical development, particularly for biologics, involves analytical challenges that don’t fit neatly into traditional categories.

An LC-MS method for characterizing post-translational modifications might measure major species (Category I), minor variants (Category II), and contribute to product identification (Category IV) simultaneously. Multivariate spectroscopic methods like NIR or Raman might predict multiple attributes across ranges spanning both major and minor components.

Rather than contorting methods to fit categories or conducting redundant validation studies to satisfy multiple category requirements, risk-based thinking asks: What do we need this method to do? What performance is necessary for those purposes? What validation evidence would demonstrate adequate performance?

This requires more analytical thinking than category-based validation, which is why many organizations resist it. Following category-based templates is easier than designing fit-for-purpose validation strategies. But template-based validation often generates massive data packages that don’t actually demonstrate whether methods will perform adequately under routine conditions.

Quality leaders should push their teams to articulate validation strategies in terms of fitness for purpose first, then verify that category-based requirements are addressed, rather than simply executing category-based templates without thinking about what they’re actually demonstrating.

Robustness: From Development to Control Strategy

Traditional validation often treated robustness as an afterthought—a set of small deliberate variations tested at the end of validation to identify factors that might influence performance. ICH Q2(R1) explicitly stated that robustness evaluation should be considered during development, not validation.

ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 formalize this by moving robustness firmly into Stage 1 development. The purpose shifts from demonstrating that small variations don’t affect performance to understanding how method parameters influence performance and establishing appropriate control strategies.

This changes what robustness studies look like. Instead of testing whether pH ±0.2 units or temperature ±2°C affect performance, enhanced approaches use design of experiments to systematically map performance across parameter ranges, identifying critical parameters that need tight control versus robust parameters that can vary within wide ranges.

The analytical control strategy emerging from this work defines what needs to be controlled, how tightly, and how that control will be verified through system suitability. Parameters proven robust across wide ranges don’t need tight control or continuous monitoring. Parameters identified as critical get appropriate control measures and verification.

Revised USP <1225> acknowledges this evolution while maintaining compatibility with traditional robustness testing for organizations using minimal development approaches. The practical implication is that organizations need to decide whether their robustness studies are compliance exercises demonstrating nothing really matters, or genuine explorations of parameter effects informing control strategies.

In my experience, most robustness studies fall into the former category—demonstrating that the developer knew enough about the method to avoid obviously critical parameters when designing the robustness protocol. Studies that actually reveal important parameter sensitivities are rare because developers already controlled those parameters tightly during development.

Platform Methods and Prior Knowledge

Biotechnology companies developing multiple monoclonal antibodies or other platform products can achieve substantial efficiency through platform analytical methods—methods developed once with appropriate robustness and then applied across products with minimal product-specific validation.

ICH Q2(R2) and revised USP <1225> both acknowledge that prior knowledge and platform experience constitute legitimate validation input. A platform charge variant method that has been thoroughly validated for multiple products can be applied to new products with reduced validation, focusing on product-specific aspects like impurity specificity and acceptance criteria rather than repeating full performance characterization.

However, organizations often claim platform status for methods that aren’t genuinely robust across the platform scope. A method that worked well for three high-expressing stable molecules might fail for a molecule with unusual post-translational modifications or stability challenges. Declaring something a “platform method” doesn’t automatically make it appropriate for all platform products.

Effective platform approaches require disciplined knowledge management documenting what’s actually known about method performance across product diversity, explicit identification of product attributes that might challenge method suitability, and honest assessment of when product-specific factors require more extensive validation.

The work-as-done reality is that platform methods often perform differently across products but these differences go unrecognized because validation strategies assume platform applicability rather than testing it. Quality leaders should ensure that platform method programs include ongoing monitoring of performance across products, not just initial validation studies.

What This Means for Investigations

The connection between analytical method validation and quality investigations is profound but often overlooked. When products fail specification, stability trends show concerning patterns, or process monitoring reveals unexpected variability, investigations invariably rely on analytical data. The quality of those investigations depends entirely on whether the analytical methods actually perform as assumed.

I’ve advocated for causal reasoning in investigations—focusing on what actually happened and why rather than cataloging everything that didn’t happen. This approach demands confidence in analytical results. If we can’t trust that our analytical methods are accurately measuring what we think they’re measuring, causal reasoning becomes impossible. We can’t identify causal mechanisms when we can’t reliably observe the phenomena we’re investigating.

The lifecycle validation paradigm, properly implemented, strengthens investigation capability by ensuring analytical methods remain fit for purpose throughout their use. Stage 3 performance verification should detect analytical performance drift before it creates false signals that trigger fruitless investigations or masks genuine quality issues that should be investigated.

However, this requires that investigation teams understand analytical method limitations and consider measurement uncertainty when evaluating results. An assay result of 98% when specification is 95-105% doesn’t necessarily represent genuine process variation if the method’s measurement uncertainty spans several percentage points. Understanding what analytical variation is normal versus unusual requires engagement with the analytical validation and ongoing verification data—engagement that happens far too rarely in practice.

Quality organizations should build explicit links between their analytical lifecycle management programs and investigation processes. Investigation templates should prompt consideration of measurement uncertainty. Trending programs should monitor analytical variation separately from product variation. Investigation training should include analytical performance concepts so investigators understand what questions to ask when analytical results seem anomalous.

The Work-as-Done Reality of Method Validation

Perhaps the most important practical implication involves honest reckoning with how validation actually happens versus how guidance documents describe it. Validation protocols present idealized experimental sequences with carefully controlled conditions and expert execution. The work-as-imagined of validation assumes adequate resources, appropriate timeline, skilled analysts, stable equipment, and consistent materials.

Work-as-done validation often involves constrained timelines driving corner-cutting, resource limitations forcing compromise, analyst skill gaps requiring extensive supervision, equipment variability creating unexplained results, and material availability forcing substitutions. These conditions shape validation study quality in ways that rarely appear in validation reports.

Organizations under regulatory pressure to validate quickly might conduct studies before development is genuinely complete, generating data that meets protocol acceptance criteria without establishing genuine confidence in method fitness. Analytical labs struggling with staffing shortages might rely on junior analysts for validation studies that require expert judgment. Equipment with marginal suitability might be used because better alternatives aren’t available within timeline constraints.

These realities don’t disappear because we adopt lifecycle validation frameworks or implement ATP concepts. Quality leaders must create organizational conditions where work-as-done validation can reasonably approximate work-as-imagined validation. This means adequate resources, appropriate timelines that don’t force rushing, investment in analyst training and equipment capability, and willingness to acknowledge when validation studies reveal genuine limitations requiring method redevelopment.

The alternative is validation theater—impressive documentation packages describing validation studies that didn’t actually happen as reported or didn’t genuinely demonstrate what they claim to demonstrate. Such theater satisfies regulatory inspections while creating quality systems built on foundations of misrepresentation—exactly the kind of organizational inauthenticity that Sidney Dekker’s work warns against.

Critical Analysis: What USP <1225> Gets Right (and Where Questions Remain)

The revised USP <1225> deserves credit for several important advances while also raising questions about implementation and potential for misuse.

Strengths of the Revision

Lifecycle integration: By explicitly connecting to USP <1220> and acknowledging ICH Q14 and Q2(R2), the chapter positions compendial validation within the broader analytical lifecycle framework. This represents significant conceptual progress from treating validation as an isolated event.

Reportable result focus: Emphasizing that validation should address the actual output used for quality decisions rather than intermediate measurements aligns validation with its genuine purpose—ensuring reliable decision-making data.

Combined accuracy-precision evaluation: Providing guidance on total error approaches acknowledges the statistical reality that these characteristics interact and should be evaluated together when appropriate.

Knowledge management: Explicit acknowledgment that development data, prior knowledge, and platform experience constitute legitimate validation inputs encourages more efficient validation strategies and better integration across analytical lifecycle stages.

Flexibility for risk-based approaches: While maintaining traditional validation categories, the revision provides conceptual space for fitness-for-purpose thinking and risk-based validation strategies.

Potential Implementation Challenges

Statistical sophistication requirements: Combined accuracy-precision evaluation and other advanced approaches require statistical expertise many analytical laboratories lack. Without adequate support, organizations might misapply statistical methods or avoid them entirely, losing the benefits the revision offers.

Interpretive ambiguity: Concepts like fitness for purpose and appropriate use of prior knowledge create interpretive flexibility that can be used constructively or abused. Without clear examples and expectations, organizations might claim compliance while failing to genuinely implement lifecycle thinking.

Resource implications: Validating with replication strategies matching routine use, conducting robust Stage 3 verification, and maintaining appropriate knowledge management all require resources beyond traditional validation. Organizations already stretched thin might struggle to implement these practices meaningfully.

Integration with existing systems: Companies with established validation programs built around traditional category-based approaches face significant effort to transition toward lifecycle validation thinking, particularly for legacy methods already in use.

Regulatory expectations uncertainty: Until regulatory agencies provide clear inspection and review expectations around the revised chapter’s concepts, organizations face uncertainty about what will be considered adequate implementation versus what might trigger deficiency citations.

The Risk of New Compliance Theater

My deepest concern about the revision is that organizations might treat new concepts as additional compliance checkboxes rather than genuine analytical challenges. Instead of honestly grappling with whether methods are fit for purpose, they might add “fitness for purpose justification” sections to validation reports that provide ritualistic explanations without meaningful analysis.

Reportable result definitions could become templates copied across validation protocols without consideration of what’s actually being reported. Replication strategies might nominally match routine use while validation continues to be conducted under unrealistically controlled conditions. Combined accuracy-precision evaluations might be performed because the guidance mentions them without understanding what the statistical intervals reveal about method performance.

This theater would be particularly insidious because it would satisfy document review while completely missing the point. Organizations could claim to be implementing lifecycle validation principles while actually maintaining traditional validation-as-event practices with updated terminology.

Preventing this outcome requires quality leaders who understand the conceptual foundations of lifecycle validation and insist on genuine implementation rather than cosmetic compliance. It requires analytical organizations willing to acknowledge when they don’t understand new concepts and seek appropriate expertise. It requires resource commitment to do lifecycle validation properly rather than trying to achieve it within existing resource constraints.

Questions for the Pharmaceutical Community

Several questions deserve broader community discussion as organizations implement the revised chapter:

How will regulatory agencies evaluate fitness-for-purpose justifications? What level of rigor is expected? How will reviewers distinguish between thoughtful risk-based strategies and efforts to minimize validation requirements?

What constitutes adequate Stage 3 verification for different method types and criticality levels? Without detailed guidance, organizations must develop their own programs. Will regulatory consensus emerge around what adequate verification looks like?

How should platform methods be validated and verified? What documentation demonstrates platform applicability? How much product-specific validation is expected?

What happens to legacy methods validated under traditional approaches? Is retrospective alignment with lifecycle concepts expected? How should organizations prioritize analytical lifecycle improvement efforts?

How will contract laboratories implement lifecycle validation? Many analytical testing organizations operate under fee-for-service models that don’t easily accommodate ongoing Stage 3 verification. How will sponsor oversight adapt?

These questions don’t have obvious answers, which means early implementers will shape emerging practices through their choices. Quality leaders should engage actively with peers, standards bodies, and regulatory agencies to help develop community understanding of reasonable implementation approaches.

Building Falsifiable Analytical Systems

Throughout this blog, I’ve advocated for falsifiable quality systems—systems designed to make testable predictions that could be proven wrong through empirical observation. The lifecycle validation paradigm, properly implemented, enables genuinely falsifiable analytical systems.

Traditional validation generates unfalsifiable claims: “This method was validated according to ICH Q2 requirements” or “Validation demonstrated acceptable performance for all required characteristics.” These statements can’t be proven false because they describe historical activities rather than making predictions about ongoing performance.

Lifecycle validation creates falsifiable claims: “This method will generate reportable results meeting the Analytical Target Profile requirements when operated within the defined analytical control strategy.” This prediction can be tested—and potentially falsified—through Stage 3 performance verification.

Every batch tested, every stability sample analyzed, every investigation that relies on analytical results provides opportunity to test whether the method continues performing as validation claimed it would. System suitability results, QC sample trending, interlaboratory comparisons, and investigation findings all generate evidence that either supports or contradicts the fundamental claim that the method remains fit for purpose.

Building falsifiable analytical systems requires:

- Explicit performance predictions: The ATP or fitness-for-purpose justification must articulate specific, measurable performance criteria that can be objectively verified, not vague assertions of adequacy.

- Ongoing performance monitoring: Stage 3 verification must actually measure the performance characteristics claimed during validation and detect degradation before methods drift into inadequate performance.

- Investigation of anomalies: Unexpected results, system suitability failures, or performance trending outside normal ranges should trigger investigation of whether the method continues to perform as validated, not just whether samples or equipment caused the anomaly.

- Willingness to invalidate: Organizations must be willing to acknowledge when ongoing evidence falsifies validation claims—when methods prove inadequate despite “passing validation”—and take appropriate corrective action including method redevelopment or replacement.

This last requirement is perhaps most challenging. Admitting that a validated method doesn’t actually work threatens regulatory commitments, creates resource demands for method improvement, and potentially reveals years of questionable analytical results. The organizational pressure to maintain the fiction that validated methods remain adequate is immense.

But genuinely robust quality systems require this honesty. Methods that seemed adequate during validation sometimes prove inadequate under routine conditions. Technology advances reveal limitations in historical methods. Understanding of critical quality attributes evolves, changing performance requirements. Falsifiable analytical systems acknowledge these realities and adapt, while unfalsifiable systems maintain comforting fictions about adequacy until external pressure forces change.

The connection to investigation excellence is direct. When investigations rely on analytical results generated by methods known to be marginal but maintained because they’re “validated,” investigation findings become questionable. We might be investigating analytical artifacts rather than genuine quality issues, or failing to investigate real issues because inadequate analytical methods don’t detect them.

Investigations founded on falsifiable analytical systems can have greater confidence that anomalous results reflect genuine events worth investigating rather than analytical noise. This confidence enables the kind of causal reasoning that identifies true mechanisms rather than documenting procedural deviations that might or might not have contributed to observed results.

The Validation Revolution We Need

The convergence of revised USP <1225>, ICH Q2(R2), and ICH Q14 represents potential for genuine transformation in how pharmaceutical organizations approach analytical validation—if we’re willing to embrace the conceptual challenges these documents present rather than treating them as updated compliance templates.

The core shift is from validation-as-event to validation-as-lifecycle-stage. Methods aren’t validated once and then assumed adequate until problems force revalidation. They’re developed with systematic understanding, validated to confirm fitness for purpose, and continuously verified to ensure they remain adequate under evolving conditions. Knowledge accumulates across the lifecycle, informing method improvements and transfer while building organizational capability.

This transformation demands intellectual honesty about whether our methods actually perform as claimed, organizational willingness to invest resources in genuine lifecycle management rather than minimal compliance, and leadership that insists on substance over theater. These demands are substantial, which is why many organizations will implement the letter of revised requirements while missing their spirit.

For quality leaders committed to building genuinely robust analytical systems, the path forward involves:

- Developing organizational capability in lifecycle validation thinking, ensuring analytical teams understand concepts beyond superficial compliance requirements and can apply them thoughtfully to specific analytical challenges.

- Creating systems and processes that support Stage 3 verification, not just Stage 2 validation, acknowledging that ongoing performance monitoring is where lifecycle validation either succeeds or fails in practice.

- Building bridges between analytical validation and other quality functions, particularly investigations, trending, and change management, so that analytical performance information actually informs decision-making across the quality system.

- Maintaining falsifiability in analytical systems, insisting on explicit, testable performance claims rather than vague adequacy assertions, and creating organizational conditions where evidence of inadequate performance prompts honest response rather than rationalization.

- Engaging authentically with what methods can and cannot do, avoiding the twin errors of assuming validated methods are perfect or maintaining methods known to be inadequate because they’re “validated.”

The pharmaceutical industry has an opportunity to advance analytical quality substantially through thoughtful implementation of lifecycle validation principles. The revised USP <1225>, aligned with ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, provides the conceptual framework. Whether we achieve genuine transformation or merely update compliance theater depends on choices quality leaders make about how to implement these frameworks in practice.

The stakes are substantial. Analytical methods are how we know what we think we know about product quality. When those methods are inadequate—whether because validation was theatrical, ongoing performance has drifted, or fitness for purpose was never genuinely established—our entire quality system rests on questionable foundations. We might be releasing product that doesn’t meet specifications, investigating artifacts rather than genuine quality issues, or maintaining comfortable confidence in systems that don’t actually work as assumed.

Lifecycle validation, implemented with genuine commitment to falsifiable quality systems, offers a path toward analytical capabilities we can actually trust rather than merely document. The question is whether pharmaceutical organizations will embrace this transformation or simply add new compliance layers onto existing practices while fundamental problems persist.

The answer to that question will emerge not from reading guidance documents but from how quality leaders choose to lead, what they demand from their analytical organizations, and what they’re willing to acknowledge about the gap between validation documents and validation reality. The revised USP <1225> provides tools for building better analytical systems. Whether we use those tools constructively or merely as updated props for compliance theater is entirely up to us.