For managers in an organization it is critical to understand and nurture the capabilities of our team members. I spend a lot of time on this blog talking about capability and competence frankly because they are an elusive concept, invisible to the naked eye. We can only perceive it through its manifestations – the tangible outputs and results produced by our team. This presents a unique challenge: how do we accurately gauge a team member’s highest level of capability?

The Evidence-Based Approach

The key to unraveling this mystery lies in evidence. We must adopt a systematic, iterative approach to testing and challenging our team members through carefully designed project work. This method allows us to gradually uncover the true extent of their competence.

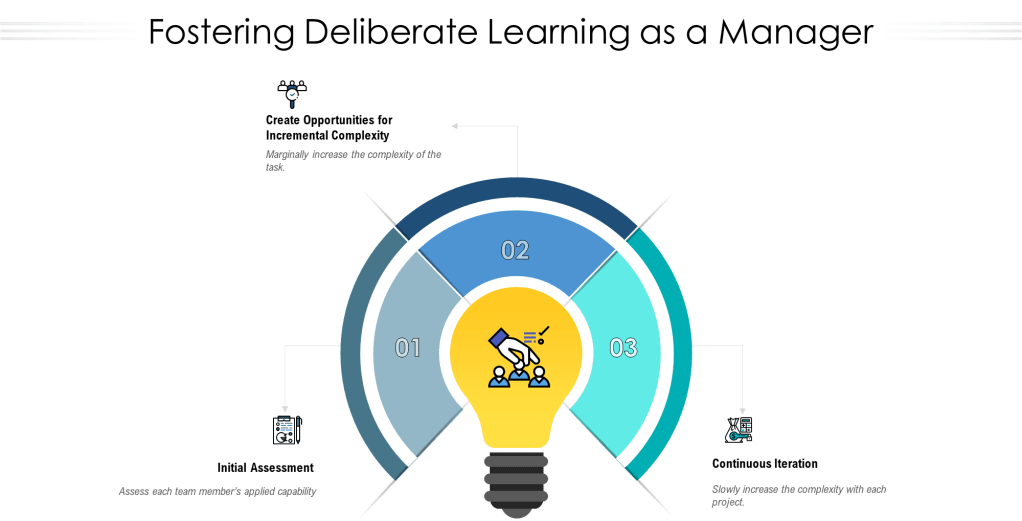

Step 1: Initial Assessment

The journey begins with a quick assessment of the team member’s current applied capability. This involves examining the fruits of their labor – the tangible outcomes of their work. As managers, we must rely on our intuitive judgment to evaluate these results. I strongly recommend this is a conversation with the individual as well.

Step 2: Incremental Complexity

Once we have established a baseline, the next step is to marginally increase the complexity of the task. This takes the form of a new project, slightly more challenging than the previous one. Crucially, we must promise a project debrief upon completion. This debrief serves as a valuable learning opportunity for both the team member and the manager.

Step 3: Continuous Iteration

If the project is successful, it becomes a springboard for the next challenge. We continue this process, incrementally increasing the complexity with each new project, always ensuring a debrief follows. This cycle persists until we reach a point of failure.

The Point of Failure: A Revelatory Moment

When a team member encounters failure, we gain invaluable insights into their competence. This moment of truth illuminates both their strengths and limitations. We now have a clearer understanding of where they excel and where they struggle.

However, this is not the end of the journey. After allowing some time for reflection and growth, we must challenge them again. This process of continual challenge and assessment should persist throughout the team member’s tenure with the organization.

The Role of Deliberate Practice

This approach aligns closely with the concept of deliberate practice, which is fundamental to the development of expertise. By providing our team members with guided practice, observation opportunities, problem-solving challenges, and experimentation, we create an environment conducive to skill development.

Building Competence

Remember, competence is a combination of capability and skill. While we cannot directly observe capability, we can nurture it through this process of continual challenge and assessment. By doing so, we also develop the skill component, as team members gain more opportunities for practice.

The Manager’s Toolkit

To effectively implement this approach, managers should cultivate several key attributes:

- System thinking: Understanding the interdependencies within projects and anticipating consequences.

- Judgment: Making rapid, wise decisions about when to increase complexity.

- Context awareness: Taking into account the unique circumstances of each team member and project.

- Interpersonal skills: Motivating and leading team members through challenges.

- Communication: Constructing and delivering clear, persuasive messages about project goals and expectations.

By embracing this evidence-based, iterative approach to assessing capability, managers can unlock the hidden potential within their teams. It’s a continuous journey of discovery, challenge, and growth – one that benefits both the individual team members and the organization as a whole.