The pharmaceutical industry stands at an inflection point in microbial control, with bacterial endotoxin management undergoing a profound transformation. For decades, compliance focused on meeting pharmacopeial limits at product release—notably the 5.0 EU/kg threshold for parenterals mandated by standards like Ph. Eur. 5.1.10. While these endotoxin specifications remain enshrined as Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), regulators now demand a fundamental reimagining of control strategies that transcends product specifications.

This shift reflects growing recognition that endotoxin contamination is fundamentally a facility-driven risk rather than a product-specific property. Health Authorities increasingly expect manufacturers to implement preventive, facility-wide control strategies anchored in quantitative risk modeling, rather than relying on end-product testing.

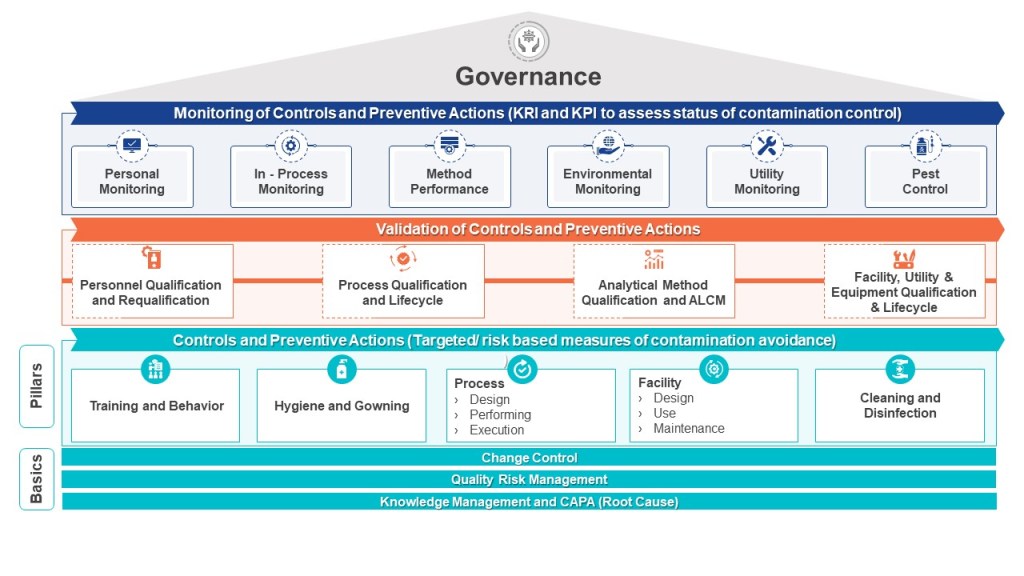

The EU Annex 1 Contamination Control Strategy (CCS) framework crystallizes this evolution, requiring cross-functional systems that integrate:

- Process design capable of achieving ≥3 log10 endotoxin reduction (LRV) with statistical confidence (p<0.01)

- Real-time monitoring of critical utilities like WFI and clean steam

- Personnel flow controls to minimize bioburden ingress

- Lifecycle validation of sterilization processes

Our organizations should be working to bridge the gap between compendial compliance and true contamination control—from implementing predictive analytics for endotoxin risk scoring to designing closed processing systems with inherent contamination barriers. We’ll examine why traditional quality-by-testing approaches are yielding to facility-driven quality-by-design strategies, and how leading organizations are leveraging computational fluid dynamics and risk-based control charts to stay ahead of regulatory expectations.

Bacterial Endotoxins: Bridging Compendial Safety and Facility-Specific Risks

Bacterial endotoxins pose unique challenges as their control depends on facility infrastructure rather than process parameters alone. Unlike sterility assurance, which can be validated through autoclave cycles, endotoxin control requires continuous vigilance over water systems, HVAC performance, and material sourcing. The compendial limit of 5.0 EU/kg ensures pyrogen-free products, but HAs argue this threshold does not account for facility-wide contamination risks that could compromise multiple batches. For example, a 2023 EMA review found 62% of endotoxin-related recalls stemmed from biofilm breaches in water-for-injection (WFI) systems rather than product-specific failures.

Annex 1 addresses this through CCS requirements that mandate:

- Facility-wide risk assessments identifying endotoxin ingress points (e.g., inadequate sanitization intervals for cleanroom surfaces)

- Tiered control limits integrating compendial safety thresholds (specifications) with preventive action limits (in-process controls)

- Lifecycle validation of sterilization processes, hold times, and monitoring systems

Annex 1’s Contamination Control Strategy: A Blueprint for Endotoxin Mitigation

Per Annex 1’s glossary, a CCS is “a planned set of controls […] derived from product and process understanding that assures process performance and product quality”. For endotoxins, this translates to 16 interrelated elements outlined in Annex 1’s Section 2.6, including:

- Water System Controls:

- Validation of WFI biofilm prevention measures (turbulent flow >1.5 m/s, ozone sanitization cycles)

- Real-time endotoxin monitoring using inline sensors (e.g., centrifugal microfluidics) complementing testing

- Closed Processing

- Material and Personnel Flow:

- Gowning qualification programs assessing operator-borne endotoxin transfer

- Raw material movement

- Environmental Monitoring:

- Continuous viable particle monitoring in areas with critical operations with endotoxin correlation studies

- Settle plate recovery validation accounting for desiccation effects on endotoxin-bearing particles

Risk Management Tools for Endotoxin Control

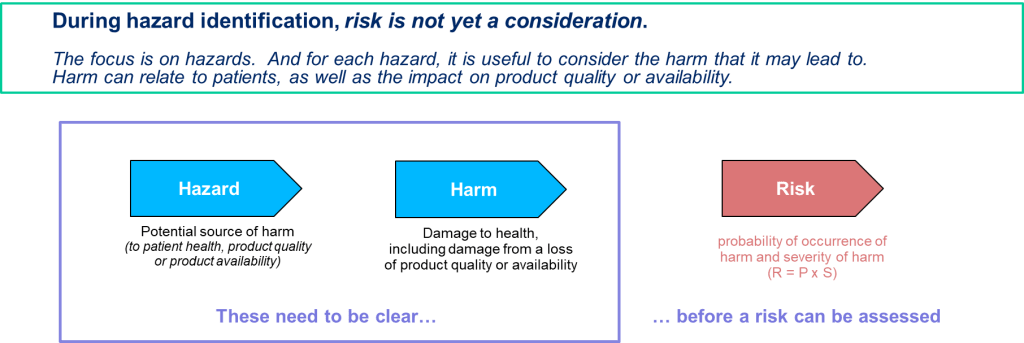

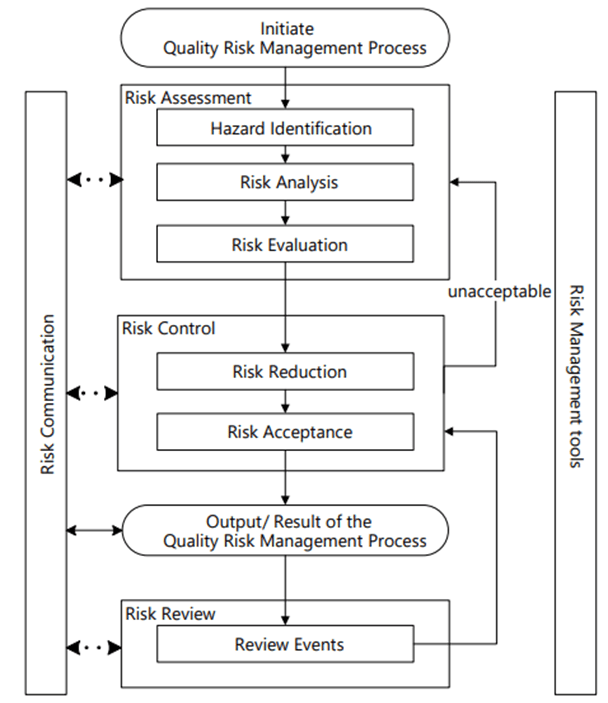

The revised Annex 1 mandates Quality Risk Management (QRM) per ICH Q9, requiring facilities to deploy appropriate risk management.

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) identifies critical control points (CCPs) where endotoxin ingress or proliferation could occur. For there a Failure Modes Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) can further prioritizes risks based on severity, occurrence, and detectability.

Endotoxin-Specific FMECA (Failure Mode, Effects, and Criticality Analysis)

| Failure Mode | Severity (S) | Occurrence (O) | Detectability (D) | RPN (S×O×D) | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFI biofilm formation | 5 (Product recall) | 3 (1/2 years) | 2 (Inline sensors) | 30 | Install ozone-resistant diaphragm valves |

| HVAC filter leakage | 4 (Grade C contamination) | 2 (1/5 years) | 4 (Weekly integrity tests) | 32 | HEPA filter replacement every 6 months |

Process Validation and Analytical Controls

As outlined in the FDA’s Process Validation: General Principles and Practices, PV is structured into three stages: process design, process qualification, and continued process verification (CPV). For bacterial endotoxin control, PV extends to validating sterilization processes, hold times, and water-for-injection (WFI) systems, where CPPs like sanitization frequency and turbulent flow rates are tightly controlled to prevent biofilm formation.

Analytical controls form the backbone of quality assurance, with method validation per ICH Q2(R1) ensuring accuracy, precision, and specificity for critical tests such as endotoxin quantification. The advent of rapid microbiological methods (RMM), including recombinant Factor C (rFC) assays, has reduced endotoxin testing timelines from hours to minutes, enabling near-real-time release of drug substances. These methods are integrated into continuous process verification programs, where action limits—set at 50% of the assay’s limit of quantitation (LOQ)—serve as early indicators of facility-wide contamination risks. For example, inline sensors in WFI systems or bioreactors provide continuous endotoxin data, which is trended alongside environmental monitoring results to preempt deviations. The USP <1220> lifecycle approach further mandates ongoing method performance verification, ensuring analytical procedures adapt to process changes or scale-up.

The integration of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) and Quality by Design (QbD) principles has transformed manufacturing by embedding real-time quality controls into the process itself. PAT tools such as Raman spectroscopy and centrifugal microfluidics enable on-line monitoring of product titers and impurity profiles, while multivariate data analysis (MVDA) correlates CPPs with CQAs to refine design spaces. Regulatory submissions now emphasize integrated control strategies that combine process validation data, analytical lifecycle management, and facility-wide contamination controls—aligning with EU GMP Annex 1’s mandate for holistic contamination control strategies (CCS). By harmonizing PV with advanced analytics, manufacturers can navigate HA expectations for tighter in-process limits while ensuring patient safety through compendial-aligned specifications.

Some examples may include:

1. Hold Time Validation

- Microbial challenge studies using endotoxin-spiked samples (e.g., 10 EU/mL Burkholderia cepacia lysate)

- Correlation between bioburden and endotoxin proliferation rates under varying temperatures

2. Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMM)

- Comparative validation of recombinant Factor C (rFC) assays against LAL for in-process testing

- 21 CFR Part 11-compliant data integration with CCS dashboards

3. Closed System Qualification

- Extractable/leachable studies assessing endotoxin adsorption to single-use bioreactor films

- Pressure decay testing with endotoxin indicators (Bacillus subtilis spores)

Harmonizing Compendial Limits with HA Expectations

To resolve regulator’s concerns about compendial limits being insufficiently preventive, a two-tier system aligns with Annex 1’s CCS principles:

| Parameter | Release Specification (EU/kg) | In-Process Action Limit | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Drug Substance | 5.0 (Ph. Eur. 5.1.10) | 1.0 (LOQ × 2) | Detects WFI system drift |

| Excipient (Human serum albumin) | 0.25 (USP <85>) | 0.05 (50% LOQ) | Prevents cumulative endotoxin load |

Future Directions

Technology roadmaps should be driving adoption of:

- AI-powered environmental monitoring: Machine learning models predicting endotoxin risks from particle counts

- Single-use sensor networks: RFID-enabled endotoxin probes providing real-time CCS data

- Advanced water system designs: Reverse osmosis (RO) and electrodeionization (EDI) systems with ≤0.001 EU/mL capability without distillation

Manufacturers can prioritize transforming endotoxin control from a compliance exercise into a strategic quality differentiator—ensuring patient safety while meeting HA expectations for preventive contamination management.