Over the past decades, as I’ve grown and now led quality organizations in biotechnology, I’ve encountered many thinkers who’ve shaped my approach to investigation and risk management. But few have fundamentally altered my perspective like Sidney Dekker. His work didn’t just add to my toolkit—it forced me to question some of my most basic assumptions about human error, system failure, and what it means to create genuinely effective quality systems.

Dekker’s challenge to move beyond “safety theater” toward authentic learning resonates deeply with my own frustrations about quality systems that look impressive on paper but fail when tested by real-world complexity.

Why Dekker Matters for Quality Leaders

Professor Sidney Dekker brings a unique combination of academic rigor and operational experience to safety science. As both a commercial airline pilot and the Director of the Safety Science Innovation Lab at Griffith University, he understands the gap between how work is supposed to happen and how it actually gets done. This dual perspective—practitioner and scholar—gives his critiques of traditional safety approaches unusual credibility.

But what initially drew me to Dekker’s work wasn’t his credentials. It was his ability to articulate something I’d been experiencing but couldn’t quite name: the growing disconnect between our increasingly sophisticated compliance systems and our actual ability to prevent quality problems. His concept of “drift into failure” provided a framework for understanding why organizations with excellent procedures and well-trained personnel still experience systemic breakdowns.

The “New View” Revolution

Dekker’s most fundamental contribution is what he calls the “new view” of human error—a complete reframing of how we understand system failures. Having spent years investigating deviations and CAPAs, I can attest to how transformative this shift in perspective can be.

The Traditional Approach I Used to Take:

- Human error causes problems

- People are unreliable; systems need protection from human variability

- Solutions focus on better training, clearer procedures, more controls

Dekker’s New View That Changed My Practice:

- Human error is a symptom of deeper systemic issues

- People are the primary source of system reliability, not the threat to it

- Variability and adaptation are what make complex systems work

This isn’t just academic theory—it has practical implications for every investigation I lead. When I encounter “operator error” in a deviation investigation, Dekker’s framework pushes me to ask different questions: What made this action reasonable to the operator at the time? What system conditions shaped their decision-making? How did our procedures and training actually perform under real-world conditions?

This shift aligns perfectly with the causal reasoning approaches I’ve been developing on this blog. Instead of stopping at “failure to follow procedure,” we dig into the specific mechanisms that drove the event—exactly what Dekker’s view demands.

Drift Into Failure: Why Good Organizations Go Bad

Perhaps Dekker’s most powerful concept for quality leaders is “drift into failure”—the idea that organizations gradually migrate toward disaster through seemingly rational local decisions. This isn’t sudden catastrophic failure; it’s incremental erosion of safety margins through competitive pressure, resource constraints, and normalized deviance.

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly. For example, a cleaning validation program starts with robust protocols, but over time, small shortcuts accumulate: sampling points that are “difficult to access” get moved, hold times get shortened when production pressure increases, acceptance criteria get “clarified” in ways that gradually expand limits.

Each individual decision seems reasonable in isolation. But collectively, they represent drift—a gradual migration away from the original safety margins toward conditions that enable failure. The contamination events and data integrity issues that plague our industry often represent the endpoint of these drift processes, not sudden breakdowns in otherwise reliable systems.

Beyond Root Cause: Understanding Contributing Conditions

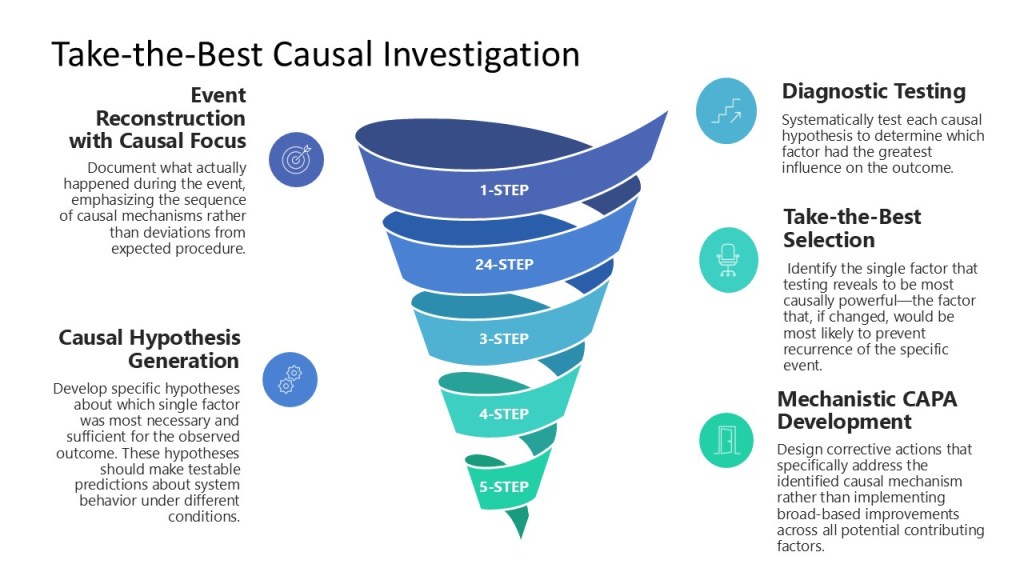

Traditional root cause analysis seeks the single factor that “caused” an event, but complex system failures emerge from multiple interacting conditions. The take-the-best heuristic I’ve been exploring on this blog—focusing on the most causally powerful factor—builds directly on Dekker’s insight that we need to understand mechanisms, not hunt for someone to blame.

When I investigate a failure now, I’m not looking for THE root cause. I’m trying to understand how various factors combined to create conditions for failure. What pressures were operators experiencing? How did procedures perform under actual conditions? What information was available to decision-makers? What made their actions reasonable given their understanding of the situation?

This approach generates investigations that actually help prevent recurrence rather than just satisfying regulatory expectations for “complete” investigations.

Just Culture: Moving Beyond Blame

Dekker’s evolution of just culture thinking has been particularly influential in my leadership approach. His latest work moves beyond simple “blame-free” environments toward restorative justice principles—asking not “who broke the rule” but “who was hurt and how can we address underlying needs.”

This shift has practical implications for how I handle deviations and quality events. Instead of focusing on disciplinary action, I’m asking: What systemic conditions contributed to this outcome? What support do people need to succeed? How can we address the underlying vulnerabilities this event revealed?

This doesn’t mean eliminating accountability—it means creating accountability systems that actually improve performance rather than just satisfying our need to assign blame.

Safety Theater: The Problem with Compliance Performance

Dekker’s most recent work on “safety theater” hits particularly close to home in our regulated environment. He defines safety theater as the performance of compliance when under surveillance that retreats to actual work practices when supervision disappears.

I’ve watched organizations prepare for inspections by creating impressive documentation packages that bear little resemblance to how work actually gets done. Procedures get rewritten to sound more rigorous, training records get updated, and everyone rehearses the “right” answers for auditors. But once the inspection ends, work reverts to the adaptive practices that actually make operations function.

This theater emerges from our desire for perfect, controllable systems, but it paradoxically undermines genuine safety by creating inauthenticity. People learn to perform compliance rather than create genuine safety and quality outcomes.

The falsifiable quality systems I’ve been advocating on this blog represent one response to this problem—creating systems that can be tested and potentially proven wrong rather than just demonstrated as compliant.

Six Practical Takeaways for Quality Leaders

After years of applying Dekker’s insights in biotechnology manufacturing, here are the six most practical lessons for quality professionals:

1. Treat “Human Error” as the Beginning of Investigation, Not the End

When investigations conclude with “human error,” they’ve barely started. This should prompt deeper questions: Why did this action make sense? What system conditions shaped this decision? What can we learn about how our procedures and training actually perform under pressure?

2. Understand Work-as-Done, Not Just Work-as-Imagined

There’s always a gap between procedures (work-as-imagined) and actual practice (work-as-done). Understanding this gap and why it exists is more valuable than trying to force compliance with unrealistic procedures. Some of the most important quality improvements I’ve implemented came from understanding how operators actually solve problems under real conditions.

3. Measure Positive Capacities, Not Just Negative Events

Traditional quality metrics focus on what didn’t happen—no deviations, no complaints, no failures. I’ve started developing metrics around investigation quality, learning effectiveness, and adaptive capacity rather than just counting problems. How quickly do we identify and respond to emerging issues? How effectively do we share learning across sites? How well do our people handle unexpected situations?

4. Create Psychological Safety for Learning

Fear and punishment shut down the flow of safety-critical information. Organizations that want to learn from failures must create conditions where people can report problems, admit mistakes, and share concerns without fear of retribution. This is particularly challenging in our regulated environment, but it’s essential for moving beyond compliance theater toward genuine learning.

5. Focus on Contributing Conditions, Not Root Causes

Complex failures emerge from multiple interacting factors, not single root causes. The take-the-best approach I’ve been developing helps identify the most causally powerful factor while avoiding the trap of seeking THE cause. Understanding mechanisms is more valuable than finding someone to blame.

6. Embrace Adaptive Capacity Instead of Fighting Variability

People’s ability to adapt and respond to unexpected conditions is what makes complex systems work, not a threat to be controlled. Rather than trying to eliminate human variability through ever-more-prescriptive procedures, we should understand how that variability creates resilience and design systems that support rather than constrain adaptive problem-solving.

Connection to Investigation Excellence

Dekker’s work provides the theoretical foundation for many approaches I’ve been exploring on this blog. His emphasis on testable hypotheses rather than compliance theater directly supports falsifiable quality systems. His new view framework underlies the causal reasoning methods I’ve been developing. His focus on understanding normal work, not just failures, informs my approach to risk management.

Most importantly, his insistence on moving beyond negative reasoning (“what didn’t happen”) to positive causal statements (“what actually happened and why”) has transformed how I approach investigations. Instead of documenting failures to follow procedures, we’re understanding the specific mechanisms that drove events—and that makes all the difference in preventing recurrence.

Essential Reading for Quality Leaders

If you’re leading quality organizations in today’s complex regulatory environment, these Dekker works are essential:

Start Here:

- The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error (3rd Edition) – Foundation for the new view approach

- Just Culture: Restorative Justice and Accountability (4th Edition) – Practical approach to accountability without blame

For Investigation Excellence:

- Behind Human Error (with Woods, Cook, et al.) – Comprehensive framework for moving beyond blame

- Drift into Failure – Understanding how good organizations gradually deteriorate

For Current Challenges:

- Safety Theater – Critique of compliance-focused approaches particularly relevant to regulated industries

- Patient Safety: A Human Factors Approach – Healthcare applications that translate well to pharmaceutical quality

The Leadership Challenge

Dekker’s work challenges us as quality leaders to move beyond the comfortable certainty of compliance-focused approaches toward the more demanding work of creating genuine learning systems. This requires admitting that our procedures and training might not work as intended. It means supporting people when they make mistakes rather than just punishing them. It demands that we measure our success by how well we learn and adapt, not just how well we document compliance.

This isn’t easy work. It requires the kind of organizational humility that Amy Edmondson and other leadership researchers emphasize—the willingness to be proven wrong in service of getting better. But in my experience, organizations that embrace this challenge develop more robust quality systems and, ultimately, better outcomes for patients.

The question isn’t whether Sidney Dekker is right about everything—it’s whether we’re willing to test his ideas and learn from the results. That’s exactly the kind of falsifiable approach that both his work and effective quality systems demand.