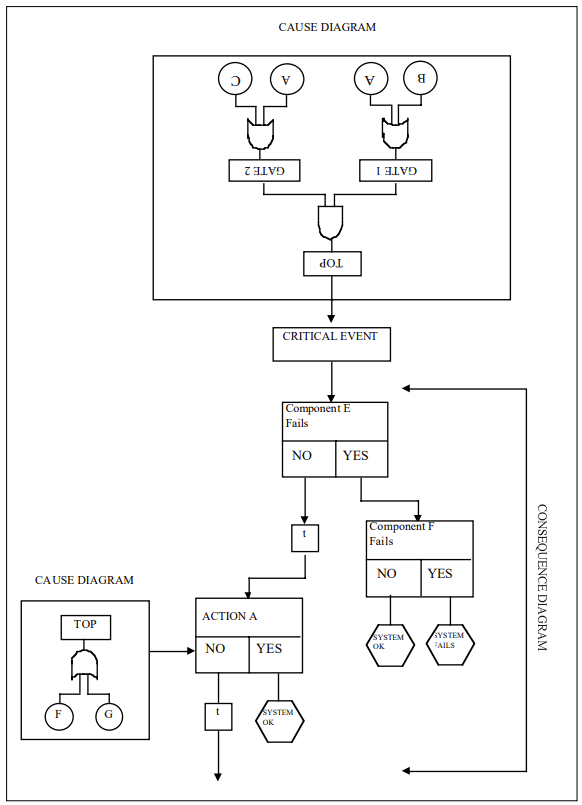

Cause-Consequence Analysis (CCA) is a versatile and comprehensive risk assessment technique that combines elements of fault tree analysis and event tree analysis. This powerful method allows analysts to examine both the causes and potential consequences of critical events, providing a holistic view of risk scenarios.

What is Cause-Consequence Analysis?

Cause-Consequence Analysis is a graphical method that integrates two key aspects of risk assessment:

- Cause analysis: Identifying and analyzing the potential causes of a critical event using fault tree-like structures.

- Consequence analysis: Evaluating the possible outcomes and their probabilities using event tree-like structures.

The result is a comprehensive diagram that visually represents the relationships between causes, critical events, and their potential consequences.

When to Use Cause-Consequence Analysis

CCA is particularly useful in the following situations:

- Complex systems analysis: When dealing with intricate systems where multiple factors can interact to produce various outcomes.

- Safety-critical industries: In sectors such as nuclear power, chemical processing, and aerospace, where understanding both causes and consequences is crucial.

- Multiple outcome scenarios: When a critical event can lead to various consequences depending on the success or failure of safety systems or interventions.

- Comprehensive risk assessment: When a thorough understanding of both the causes and potential impacts of risks is required.

- Decision support: To aid in risk management decisions by providing a clear picture of risk pathways and potential outcomes.

How to Implement Cause-Consequence Analysis

Implementing CCA involves several key steps:

1. Identify the Critical Event

Start by selecting a critical event – an undesired occurrence that could lead to significant consequences. This event serves as the focal point of the analysis.

2. Construct the Cause Tree

Working backwards from the critical event, develop a fault tree-like structure to identify and analyze the potential causes. This involves:

- Identifying primary, secondary, and root causes

- Using logic gates (AND, OR) to show how causes combine

- Assigning probabilities to basic events

3. Develop the Consequence Tree

Moving forward from the critical event, create an event tree-like structure to map out potential consequences:

- Identify safety functions and barriers

- Determine possible outcomes based on the success or failure of these functions

- Include time delays where relevant

4. Integrate Cause and Consequence Trees

Combine the cause and consequence trees around the critical event to create a complete CCA diagram.

5. Analyze Probabilities

Calculate the probabilities of different outcome scenarios by combining the probabilities from both the cause and consequence portions of the diagram.

6. Evaluate and Interpret Results

Assess the overall risk picture, identifying the most critical pathways and potential areas for risk reduction.

Benefits of Cause-Consequence Analysis

CCA offers several advantages:

- Comprehensive view: Provides a complete picture of risk scenarios from causes to consequences.

- Flexibility: Can be applied to various types of systems and risk scenarios.

- Visual representation: Offers a clear, graphical depiction of risk pathways.

- Quantitative analysis: Allows for probability calculations and risk quantification.

- Decision support: Helps identify critical areas for risk mitigation efforts.

Challenges and Considerations

While powerful, CCA does have some limitations to keep in mind:

- Complexity: For large systems, CCA diagrams can become very complex and time-consuming to develop.

- Expertise required: Proper implementation requires a good understanding of both fault tree and event tree analysis techniques.

- Data needs: Accurate probability data for all events may not always be available.

- Static representation: The basic CCA model doesn’t capture dynamic system behavior over time.

Cause-Consequence Analysis is a valuable tool in the risk assessment toolkit, offering a comprehensive approach to understanding and managing risk. By integrating cause analysis with consequence evaluation, CCA provides decision-makers with a powerful means of visualizing risk scenarios and identifying critical areas for intervention. While it requires some expertise to implement effectively, the insights gained from CCA can be invaluable in developing robust risk management strategies across a wide range of industries and applications.

Cause-Consequence Analysis Example

| Process Step | Potential Cause | Consequence | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream Bioreactor Operation | Leak in single-use bioreactor bag | Contamination risk, batch loss | Use reinforced bags with pressure sensors + secondary containment |

| Cell Culture | Failure to maintain pH/temperature | Reduced cell viability, lower mAb yield | Real-time monitoring with automated control systems |

| Harvest Clarification | Pump malfunction during depth filtration | Cell lysis releasing impurities | Redundant pumping systems + surge tanks |

| Protein A Chromatography | Loss of column integrity | Inefficient antibody capture | Regular integrity testing + parallel modular columns |

| Viral Filtration | Membrane fouling | Reduced throughput, extended processing time | Pre-filtration + optimized flow rates |

| Formulation | Improper mixing during buffer exchange | Product aggregation, inconsistent dosing | Automated mixing systems with density sensors |

| Aseptic Filling | Breach in sterile barrier | Microbial contamination | Closed system transfer devices (CSTDs) + PUPSIT testing |

| Cold Chain Storage | Temperature deviation during freezing | Protein denaturation | Controlled rate freeze-thaw systems + temperature loggers |

Key Risk Areas and Systemic Impacts

1. Contamination Cascade

Single-use system breaches can lead to:

- Direct product loss ($500k-$2M per batch)

- Facility downtime for decontamination (2-4 weeks)

- Regulatory audit triggers

2. Supply Chain Interdependencies

Delayed delivery of single-use components causes:

- Production schedule disruptions

- Increased inventory carrying costs

- Potential quality variability between suppliers

3. Environmental Tradeoffs

While reducing water/energy use by 30-40% vs stainless steel, single-use systems introduce:

- Plastic waste generation (300-500 kg/batch)

- Supply chain carbon footprint from polymer production

Mitigation Effectiveness Analysis

| Control Measure | Risk Reduction (%) | Cost Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Automated monitoring systems | 45-60 | High initial investment |

| Redundant fluid paths | 30-40 | Moderate |

| Supplier qualification | 25-35 | Low |

| Staff training programs | 15-25 | Recurring |

This analysis demonstrates that single-use mAb manufacturing offers flexibility and contamination reduction benefits, but requires rigorous control of material properties, process parameters, and supply chain logistics. Modern solutions like closed-system automation and modular facility designs help mitigate key risks while maintaining the environmental advantages of single-use platforms.